At 7:41 a.m. CST on 28 February 1966, a pair of sleek T-38 Talon jets took off from Ellington Field, not far from the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC)—on the site of today’s Johnson Space Center (JSC)—in Houston, Texas, bound for Lambert Field in St. Louis, Miss. Aboard the lead jet, tailnumbered “NASA 901”, were astronauts Elliot See and Charlie Bassett, prime crew for the upcoming Gemini IX mission, targeted for May of that year.

Following them in the second T-38, tailnumbered “NASA 907”, were their backups, Tom Stafford and Gene Cernan. Flight rules forbade a member of a prime crew to fly with his counterpart on the backup crew, lest an accident wipe out the entire specialty for one seat on the mission. Tragically, those rules held firm on the fateful morning of 28 February 1966.

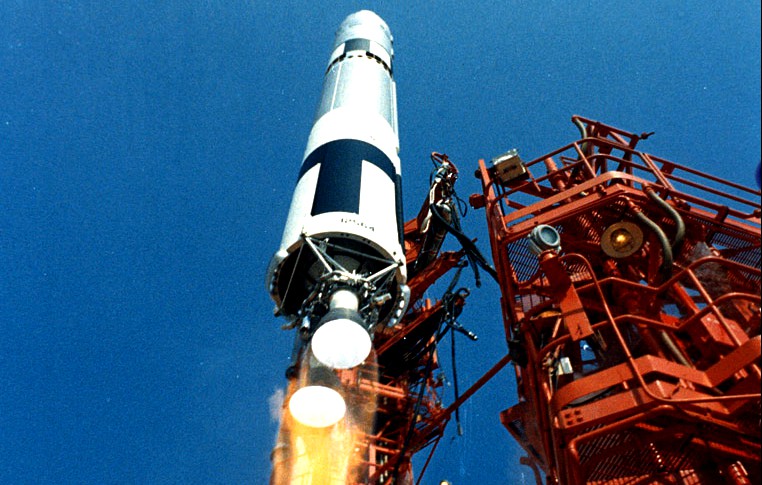

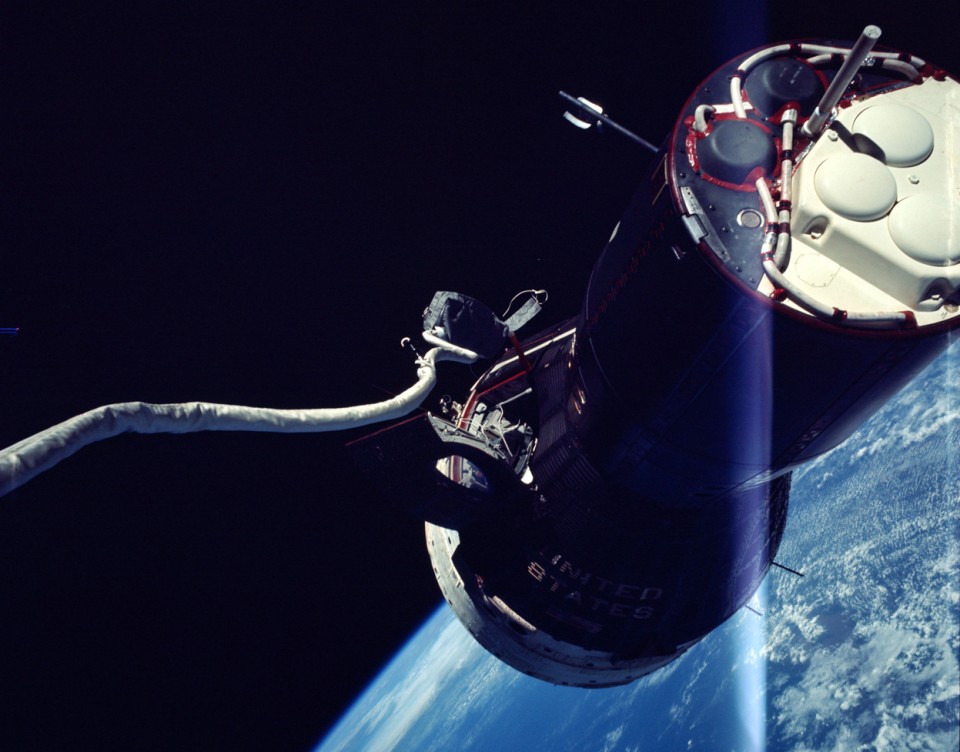

Thirty-eight-year-old civilian test pilot See and 34-year-old Air Force major Bassett had been assigned to Gemini IX in November 1965. Their flight would last up to three days and would feature rendezvous and docking with an unpiloted Gemini-Agena Target Vehicle (GATV) and a spacewalk by Bassett to evaluate an experimental propulsive backpack, known as the Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU).

Over the last several months, See had flown 25 times and Bassett seven times to St. Louis, to visit McDonnell Aircraft Corp., where Gemini IX was being built and tested. It was a short 90-minute flight and on 28 February 1966 the men and their backups were headed there for two weeks of rendezvous training in the Gemini simulator. It would also afford them a chance to see the spacecraft that they would soon fly.

Sadly, the flight that morning would end with the deaths of See and Bassett and approached within a hair’s breadth of destroying Gemini IX itself.

The days leading up to the fateful day had been uneventful. On the 27th, See and his family attended a religious service in downtown Houston, followed by the Livestock Show and Rodeo in the Astrodome. Bassett accompanied them to the rodeo.

Early the next morning, the men arose, with See breakfasting on cereal, juice and toast and Bassett taking a run, before enjoying his own hot breakfast and coffee. Then the pair headed for the Ellington Field flight line. They filed their flight plans and loaded the baggage for themselves and Stafford and Cernan into NASA 901.

Following takeoff, the two aircraft reached a cruising altitude of 41,000 feet (12,500 meters) and traveled in formation. “As Stafford eased up into position on See’s wing, he and Cernan could easily make out the other two pilots with their white helmets,” wrote space historians Colin Burgess, Kate Doolan and Bert Vis in Fallen Astronauts.

Forty minutes into the flight, a radio check with the Little Rock Air Force Base Meteorological Office advised the crews that there was an overcast ceiling of 600 feet (180 meters) at St. Louis, visibility of two miles (3.2 km) and rain and fog. Conditions were not expected to change significantly prior to the astronauts’ arrival in Missouri.

As the four astronauts approached St Louis, the morning grew darker and the flying conditions murkier, with thick cloud, poor visibility and rain and snow flurries. At 8:48 a.m. CST, Lambert Field airport, situated close to McDonnell’s plant, expected the astronauts to follow standard procedures and execute instrument-based landings.

Descending through the cloud deck, the two jets appeared directly over the centerline of Lambert Field’s southwest runway at 8:55 a.m. Both were too low and traveling too fast to land. Up until this point, Stafford had remained in position on See’s right wing, but opted to ascend and perform another approach. He assumed that See would do the same.

But inexplicably, See executed a tight turn to reach the runway. Years later, the only explanation for why he did this was that he wanted to land before the backup crew; an unusual act for a pilot who had earned repute for care and judiciousness.

As See and Bassett’s jet vanished from sight, Stafford barked to Cernan in his backseat: “Goddammit, where’s he going?”

It was the last they ever saw of their comrades.

Minutes later, Stafford’s irritation mounted, for the Lambert Field air traffic controllers had virtually ignored him and were vague in their communications. At length, he was close to declaring an emergency, so low was his fuel gauge, but eventually Stafford set NASA 907 safely onto the runway. He was puzzled by an odd question from the control tower.

“Who was in NASA 901?”

“See and Bassett,” he replied.

He was told that McDonnell Aircraft had “a message” for him. A few minutes later, as Stafford opened his canopy, there was James McDonnell—“Mr. Mac” himself, aviation pioneer and founder of McDonnell Aircraft Corp.—waiting for them. In solemn tones, he explained that See and Bassett were dead.

Over the course of the next few days, a picture of what happened became clear. After leaving Stafford and Cernan’s sight, it appeared that See realized he was heading directly for McDonnell Building 101—the very building in which Gemini IX was being built—and that he could not land safely.

Union Electric company linesman Kenneth Stovall was walking through a parking lot near the McDonnell plant when he heard the T-38 approaching. Quoted by Burgess, Doolan and Vis, he remembered seeing the aircraft descending at “a fairly sharp angle” and suddenly cutting in the afterburners.

From the front seat, See lit the afterburners, broke hard right and pulled back on the stick, but his actions came far too late. As evidenced in the subsequent accident investigation, only three seconds elapsed between See selecting afterburners and the moment of impact, by which time the right afterburner was in full thrust and its left-side counterpart was in the process of building power. Meanwhile, on the ground, Stovall lost visual contact with the T-38 as it disappeared behind some stationary boxcars on the elevated railroad tracks at the northern end of the airfield.

“I heard a roar and saw a ball of fire,” he said later. “I knew the pilots would be killed.” At 8:58 a.m. CST, the T-38 grazed the roof of Building 101, lost its starboard wing, cartwheeled into a nearby parking lot and exploded into flames.

Inside Building 101, foreman Damien Meert watched, aghast, from his desk as a sheet of flame rippled across the corrugated iron roof. His workers dived for cover under benches as fragments from the T-38’s shattered wing flooded into the building.

Other workers heard noises which they variously described as resembling sonic booms or the echo of thunder, as well as sudden flashes of fire and the manifestation of clouds of dust and fumes. About a dozen people were injured by falling ceiling debris, including 19-year-old production worker Clyde Ethridge, who sustained a serious back injury.

Firefighters and police quickly converged on the crash site and sealed it off, as a mass of foam was dumped onto the fuselage as a precautionary measure against fire. Elliot See had been thrown clear of the fuselage and his body was found in the parking lot, his parachute half-opened. The gruesome discovery of Charlie Bassett’s severed head, jammed high in the rafters of Building 101, came later that day.

Even the identification of the remains was difficult and was not aided by the fact that all four men’s identification papers were in the baggage pod of See and Bassett’s jet. Only by checking with the men who were still alive was it possible to work out who had died.

Dr. Eugene Tucker from the St. Louis County Hospital, who performed the autopsy, described the injuries as not unlike those incurred by victims of a head-on traffic collision. Both men died just 500 feet (150 meters) from their Gemini IX spacecraft.

Miracles seemed far from St Louis during that gloomy day on which See and Bassett breathed their last, but it is quite remarkable that no one on the ground was seriously injured and their spacecraft, Gemini IX, survived. If their T-38 had been lower when it hit Building 101, See and Bassett would have ploughed into the assembly line, destroying Gemini IX and killing hundreds of McDonnell’s skilled spacecraft construction workers.

“Had they hit a couple of hundred feet earlier,” wrote Tom Stafford in his memoir, We Have Capture, “they would have hit the side and roof of the building, instead of just the end of the roof, and wiped out the whole Gemini program.” Project Gemini, which provided an indispensable stepping-stone to the Moon, would have been over.

Two days after the tragedy, with Stafford and Cernan now reassigned as Gemini IX’s prime crew, the spacecraft was loaded aboard a C-124 transport aircraft for delivery to Cape Kennedy in Florida. And on 4 March, the entire astronaut corps gathered at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Va., as See and Bassett were laid to rest.

An investigative board, chaired by Chief Astronaut Alan Shepard, found no defects in the T-38 and no problems with the physical or psychological state of See or Bassett. On paper, both men’s flying credentials were outstanding and both had renewed their instrument flying certificates within the last six months. The appalling weather was a contributory factor, but the board’s eventual consensus of “Pilot Error” came as no surprise.

See was the only astronaut whose flying skills worried Deke Slayton, the head of Flight Crew Operations. The high-performance T-38 was unforgiving of errors and could easily stall at speeds of less than 270 knots; Slayton felt that See was overly cautious, flew too slowly and did not have the aggressive flying streak that the jet demanded of its pilots.

Years later, in his memoir Deke, he admitted that he had gotten “sentimental” about See and gave him command of Gemini IX in the hope that Bassett would be strong enough to carry them both. Ultimately, he wrote, “it was a bad call”.

Others, including Neil Armstrong, were more sympathetic. “There might have been other considerations that we’re not even aware of,” he told his biographer, James Hansen, in First Man. “I would not begin to say that his death proves the first thing about his qualification as an astronaut.”

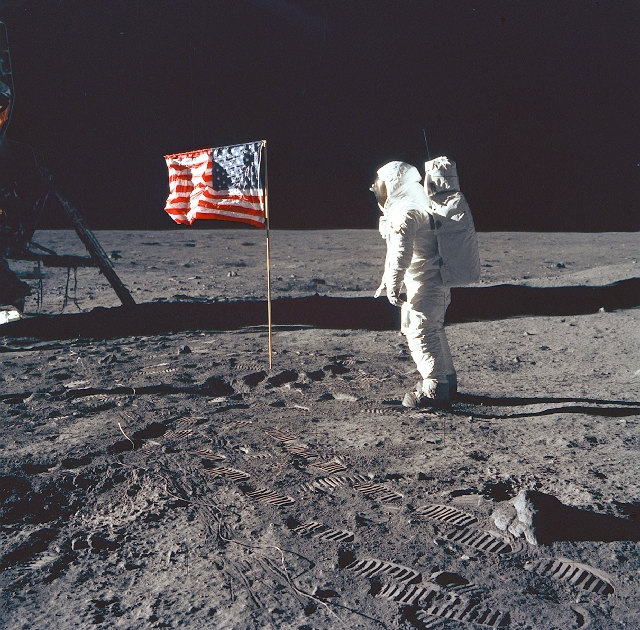

Of all the tragedies and disasters which affected America’s space program in the 1960s, the accident which claimed See and Bassett had greater consequences than could be anticipated at the time. Three weeks after their deaths, Slayton named Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin as Gemini IX’s new backup crew and the two men went on to fly Gemini XII—the final mission in the program—in November 1966.

Had it not been for the accident, this change of circumstances almost certainly would not have gone on to position Aldrin to be Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) of Apollo 11 or the second man to walk on the Moon. This tragic irony was not lost on Aldrin, for whom Charlie Bassett had been a close friend and a neighbor.

In his memoir, Deke Slayton wrote that had the accident not occurred and had Gemini IX flown successfully, See would likely have gone on to serve as backup command pilot for Gemini XII, before possibly rotating into the Apollo Applications Program (AAP), which later became Skylab. Meanwhile, Bassett was pointed toward a role as senior pilot for one of the early Apollo missions, which might have suitably positioned him to command a lunar landing flight.

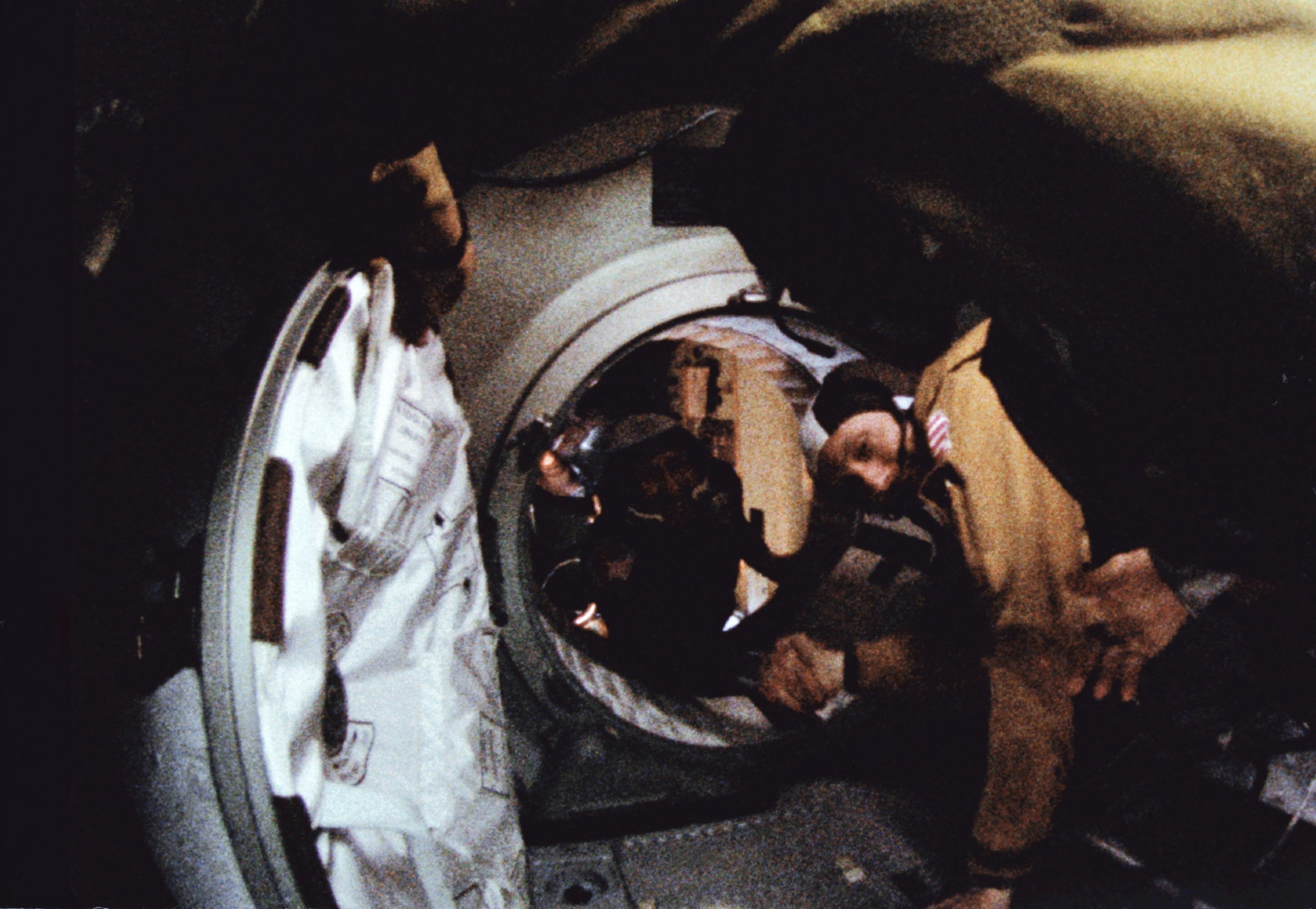

Moreover, the two men who ultimately flew the mission, redesignated “Gemini IX-A”, in June 1966, would later carve their own niches in history: Stafford would command the final dress rehearsal for the first lunar landing, whilst Cernan is still known to history as the “Last Man on the Moon”.