The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is one step closer to reaching the Red Planet, following yesterday’s rousing liftoff of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), carrying the long-awaited Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM). Also known as “Mangalyaan”—Hindi for “Mars Craft”—the mission rocketed away from the First Launch Pad at the Satish Dhawan Space Centre, on the barrier island of Sriharikota, within India’s southern province of Andhra Pradesh, precisely on time at 2:38 p.m. IST (4:08 a.m. EST) Tuesday, 5 November. The countdown, which began early Sunday, proceeded flawlessly, and MOM/Mangalyaan will now spend about three weeks executing six maneuvers of its Liquid Apogee Motor (LAM) to gradually expand the apogee of its orbit. On 30 November, it will achieve “escape velocity” and enter heliocentric orbit, beginning a 10-month journey to reach Mars on 24 September 2014.

Yesterday’s launch was the 25th by the workhorse PSLV and the fifth in its extended “XL” configuration. First flown in September 1993, the four-stage rocket has one of the most reliable track records in the world, having suffered just one failure—ironically on its maiden voyage, which suffered an attitude-control system malfunction and plummeted into the Bay of Bengal, 700 seconds after liftoff—and has the capability to insert payloads of up to 7,160 pounds (3,250 kg) into low-Earth orbit and up to 3,100 pounds (1,410 kg) into geostationary transfer orbit. It was thus ideally suited to loft the 2,980-pound (1,350-kg) MOM/Mangalyaan spacecraft. Standing 144 feet (44 meters) tall, the PSLV family has delivered payloads into orbit on behalf of India, Germany, South Korea, Norway, Italy, Luxembourg, Indonesia, Argentina, Israel, Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, Denmark, Switzerland, Turkey, Algeria, Singapore, Russia, Austria, the United Kingdom, and France.

Final preparations for the MOM/Mangalyaan launch entered high gear following a successful Launch Rehearsal on Friday, 1 November and the formal start of the 56.5-hour countdown at 6:08 a.m. IST Sunday, 3 November. Filling of the PSLV’s liquid-fueled PS4 fourth stage and Reaction Control Thrusters with monomethyl hydrazine (MMH) and Mixed Oxides of Nitrogen (MON) was completed late Sunday night, and on Monday the liquid propellants of the PS2 second stage were loaded. Shortly thereafter, the Mobile Service Tower withdrawal up to 160 feet (50 meters) was completed and it was retracted to its “parked” position—490 feet (150 meters) from the pad—early Tuesday. At 6:08 a.m. IST, the 8.5-hour final portion of the countdown was initiated and all PSLV systems were activated in readiness for the impending launch attempt.

With 15 minutes remaining before liftoff, and with weather conditions and all systems classified as “Green,” at 2:24 p.m. IST the Mission Director issued a formal “Go for Launch” and the rocket’s autosequencer assumed primary control of vehicle critical functions. At precisely 2:38:00 p.m. IST (T-0), the single engine of the PS1 first stage—generating a maximum 1.1 million pounds (500,000 kg) of thrust—ignited and ramped up to full power, ahead of the commands to fire four of the six side-mounted Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) in two pairs. The first pair came online at T+0.5 seconds, followed by the second pair at T+0.7 seconds, and the PSLV left the pad and took flight at 2:38:03 p.m. (T+3 seconds). Clearing the tower with a crackling roar, the rocket established itself onto the proper flight azimuth, rolling onto a 104-degree heading, and at T+25 seconds, as planned, the remaining pair of SRBs were ignited at an altitude of 2 miles (3.2 km). “These help to push the PSLV through the area of maximum dynamic pressure,” noted AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker.

The “ground-lit” SRBs burned out and separated from the vehicle a little over a minute into the ascent, whilst their “air-lit” counterparts expired their propellant at 2:39:15 p.m. IST and separated 17 seconds later. All six boosters splashed down in the western Bay of Bengal. Under the continued impulse of the first stage engine, the PSLV powered upward, finally separating at 2:39:55 p.m. IST at an altitude of 35 miles (56 km) and handing the baton over to the PS2 second stage, whose liquid-fed Vikas engine pushed the stack higher into the rarefied atmosphere. Burning for 2.5 minutes, the flight of the second stage also saw the jettison of the payload fairing—emblazoned with the Indian national flag and the proud MOM/Mangalyaan mission logos—and concluded at 2:42:27 p.m. IST at an altitude of 80 miles (128 km) above Earth. The solid-fueled third stage continued the mission, burning for 112 seconds and separating at 2:46:41 p.m.

According to debris danger maps published by NASASpaceflight.com, the PSLV’s first two stages and the six strap-on boosters were expected to impact the western Bay of Bengal after being jettisoned. The third stage was predicted to splash down in the central Andaman Sea, far to the east of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, after which the vehicle coasted eastward for around 35 minutes, passing over the Malaysian Peninsula and eventually out over the Pacific Ocean. In the words of AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker, the purpose of this coasting phase was “to enable the spacecraft to be inserted into the correct Transfer Orbit for the onward journey to Mars.”

A lengthy period of telemetry blackout ended at 3:11:44 p.m. IST, when the two ISRO tracking ships—the Marine Vessels (MV) SCI Nalanda and Yamuna, both located in the waters of the South Pacific since late last month—reacquired the PS4 fourth stage of the PSLV and its attached MOM/Mangalyaan payload. “These mobile tracking stations,” explained the Launch Tracker, “have now locked on to the spacecraft and are showing a nominal track slightly above the expected flight plan. The on-board guidance will correct this before spacecraft release.” Shortly afterwards, the liquid-fueled PS4 stage ignited to inject MOM/Mangalyaan into space. “This was a particular concern,” noted the Tracker, “as a coast phase of this length has not been attempted before with the PSLV, but is a requirement of the orbital mechanics to ensure that the spacecraft achieves the exact orbit to enable it to slingshot out to Mars.”

At 3:23:26 p.m. IST, Orbital Insertion was jubilantly confirmed and the fourth stage duly shut down and separated. Its impact footprint was anticipated to fall within a virtually uninhabited stretch of the South Pacific, to the west of Ecuador and Peru. The slight over-performance of the burn was realigned to the flight plan by the rocket’s guidance system and within minutes ISRO formally announced that the MOM/Mangalyaan payload had been placed very precisely into the desired elliptical orbital path around Earth. Forty-four minutes and 17 seconds after leaving the Satish Dhawan Space Centre, India’s first foray to the Red Planet had cleared its first major hurdle.

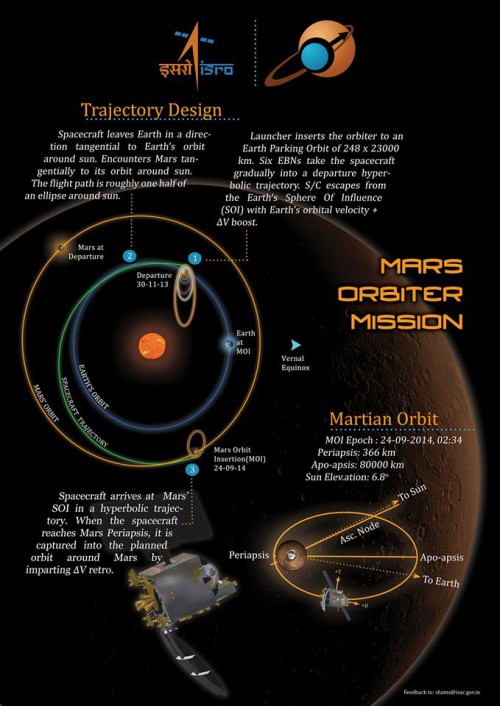

MOM/Mangalyaan is currently healthy and will execute a series of six firings of its Liquid Apogee Motor (LAM) over the next three weeks to expand its orbit to an apogee of 133,600 miles (215,000 km) and a perigee of 370 miles (600 km). On 30 November, if all goes well, it will achieve “escape velocity” and enter heliocentric orbit, beginning a 10-month voyage to reach Mars in September 2014. “The spacecraft leaves Earth in a direction tangential to Earth’s orbit,” explained ISRO’s official brochure for the mission, “and encounters Mars tangentially to its orbit,” noting that these “minimum-energy” opportunities to reach the Red Planet under conditions of the best economy of propellant expenditure, mission duration, and trajectory design arise approximately every 780 days.

“The spacecraft arrives at the Mars Sphere of Influence in a hyperbolic trajectory,” continued ISRO. “At the time the spacecraft reaches the Closest Approach to Mars (periapsis), it is captured into planned orbit around Mars by impacting delta-V retro, which is called the Mars Orbit Insertion (MOI) manoeuvre.” According to current mission plans, MOI will occur at 2:34 a.m. IST on 24 September 2014 (5:04 p.m. EDT on 23 September), and MOM/Mangalyaan will enter an orbit of 310 x 50,000 miles (500 x 80,000 km), inclined 150 degrees. In this highly elliptical orbit, it will circle the planet once every 76.72 hours. Quoting ISRO officials, FirstPost India noted that the minimum life of MOM/Mangalyaan in Mars orbit is six months, but hopes are high that it will exceed this target.

This mission is both highly ambitious and highly unlikely for the world’s second most populous nation, and its merits and motivations have triggered considerable debate. It is described as “a technology demonstration project,” and its primary task is to prove that India can design, plan, manage, launch, and operate a deep-space mission across the enormous gulf to reach the Red Planet. It only received formal approval and a $41 million financial injection from the Indian government in August 2012. With anticipated costs as high as $100 million, the mission has unsurprisingly provoked debate from critics who feel that India could better spend the money on more down-to-earth issues, such as power failures, droughts, and the aftermath of Cyclone Phailin. Still, one government official retorted in a BBC interview that “if we don’t dare dream big, it would just leave us as hewers of wood and drawers of water,” noting that “India is today too big to be just living on the fringes of high technology.”

Equipped with five scientific instruments—the Methane Sensor for Mars (MSM), Mars Colour Camera (MCC), Mars Exospheric Neutral Composition Analyser (MENCA), Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (TIR), and Lyman-Alpha Photometer (LAP)—the MOM/Mangalyaan spacecraft is dedicated to developing a better understanding of the morphology, topography, and mineralogy of the Martian surface, together with the dynamics of its thin upper atmosphere, its loss of water, the influence of solar wind and radiation, and the nature of its moons, Phobos and Deimos. According to ISRO, the payloads were chosen by the Advisory Committee on Space Sciences (ADCOS).

Hopes are high for MOM/Mangalyaan, as India sets out on a path to become the fourth discrete organization, nation, or group of nations to successfully send its own mission to Mars. Only Russia, the United States, and the member states of the European Space Agency (ESA) have accomplished this feat to date. Yet the stakes are even higher, particularly in the wake of the ignominious failure of Russia’s Fobos-Grunt and China’s Yinghuo-1 spacecraft, which failed to leave Earth orbit in November 2011 and burned up in the atmosphere a few weeks later. “For Mars, there were 51 missions so far the world around,” ISRO Chairman Dr. K. Radhakrishnan told India’s Economic Times last week, “and there were 21 successful missions. It’s a complex mission.” He pointed out that the difference between success and failure in any space enterprise “is very, very thin,” but stressed that even a failure provides a stepping stone to success. Coming less than two years after the Fobos-Grunt and Yinghuo-1 failure, Dr. Radhakrishnan denied overt competition with China and scoffed at the notion of a “race” to Mars between the two nations. “We are in competition with ourselves,” he said, “in the areas that we have charted for ourselves. Each country has its own priorities.”

Dr. Radhakrishnan has admitted that the MOM/Mangalyaan mission will be a challenge, an opportunity, and a matter of national pride, and certainly illustrates the growing maturity of India’s space program. “Such scientific missions post very tough challenges to technologists,” he said. “Some of the outcomes—for example, the in-built autonomy we are providing in this spacecraft—can become a reality as a product or system and be used in satellites to improve their efficiency. So they percolate to application, which is our main objective. It could be something like forecasting cyclones. There is always relevance for a mission such as this.”

The spacecraft’s in-built autonomy has been incorporated in response to a recognition that the maximum Earth-Mars Round Trip Light Time (RLT) will be 42 minutes, making it “impractical to micromanage the mission from Earth with ground intervention.” As a consequence, MOM/Mangalyaan adopts autonomous Fault Detection, Isolation, and Reconfiguration (FDIR) logic, none of whose actions will disrupt the spacecraft’s Earth Pointing Attitude. ISRO considers this system to be essential during any communications problems or interruptions—during eclipses, for example—and it will safeguard the spacecraft during its insertion into Martian orbit.

Conditions in interplanetary space and in orbit around the Red Planet have also been simulated during numerous ground tests. The performance characteristics of the critical Liquid Apogee Motor have been evaluated in ISRO’s High Altitude Test Facility, whilst thermal balance tests have yielded baseline data for Mars radiation flux and have helped to validate thermal models. In order to handle the frigid cold of a Martian eclipse, MOM/Mangalyaan solar array “coupons” have been subjected to temperature conditions as low as -200 degrees Celsius, qualifying both the cells and their bonding agents. The spacecraft’s communications system has been exhaustively tested and verified by both ISRO and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) of Pasadena, Calif., whose Deep Space Network (DSN) will work alongside the Indian Deep Space Network (IDSN) in tracking MOM/Mangalyaan. These tests have demonstrated “communications management” at the predicted distance between Earth and Mars at the point of MOI, an estimated 133 million miles (214 million km), and after six months in orbit, an estimated 233 million miles (375 million km).

Much criticism has been leveled at India in recent weeks, with some observers expressing open condemnation that ISRO is executing such a mission when it has pressing problems at home. The process of reconstruction in the wake of Cyclone Phailin’s ravages is still underway, and last year’s droughts, coupled with endemic poverty in the country, are both noteworthy and worrisome. Yet questions of the wisdom of “wasting” money on a space program have been asked time and again throughout history. Some have argued that space exploration, by its very nature, plays a key role in advancing a nation in a technological sense and helping to position its people onto the world stage. Last year, an Indian government official told the BBC that “if we don’t dare dream big, it would just leave us as hewers of wood and drawers of water.” Whatever our individual perspectives might be, on the eve of India’s first voyage to Mars we can be certain of one thing: that these hewers and wood and drawers of water have collectively accomplished something quite remarkable.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » MOM »

Excellent article…I find this amazing at the low cost such an endeavor has been proposed…If successful this will open the door to missions that might be put together by universities or even wealthy individuals…India is certainly changing the world including utilizing an AI software solution for orbital insertion into Mars orbit…So I guess the trend is to further the lowering cost of space access and exploration by factors of 2 or 3…