Twelve years ago, last weekend, Shuttle Columbia and the crew of STS-107—Commander Rick Husband, Pilot Willie McCool, Mission Specialists Dave Brown, Kalpana Chawla, Mike Anderson, and Laurel Clark, and Israeli Payload Specialist Ilan Ramon—were lost during re-entry, shortly before their scheduled landing at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), Fla. Unlike the ill-fated Challenger, theirs was not a voyage barely begun, but rather a voyage almost at its conclusion, with all but the final 16 minutes of their 16-day mission behind them. At the time of the disaster, that terrible Saturday morning, a further five flights and no fewer than 18 shuttle-based EVAs were scheduled to follow STS-107, all of them bound for the International Space Station (ISS) and all of them tasked with installing hardware to virtually complete the football-field-sized Integrated Truss Structure (ITS) and prepare for the arrival of pressurized modules from the United States, Europe, and Japan.

And on the morning of Saturday, 1 February 2003, astronaut Eileen Collins was at home with her toddler son in Houston, Texas, exactly four weeks away from her own return to space in command of STS-114. Her pilot, Jim Kelly, was taking one of his sons to a band competition. “I check on flights when they’re airborne,” Kelly later told a NASA interviewer. “I checked on it before I left the house and everything was going fine. I got the phone call from my wife and came directly into work.” For Collins and Kelly, as with the other “core” members of the STS-114 crew—Mission Specialists Steve Robinson and Japanese astronaut Soichi Noguchi—the shock of losing their friends and colleagues came as a delayed reaction, as they plunged into the effort to recover from the tragedy.

Under the original plan, STS-114 was designated as the first Utilization and Logistics Flight (ULF-1) and would transport the Italian-built Raffaello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) and attach it by means of the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm onto the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Unity node. Laden with equipment and supplies for the station’s incumbent crew, Atlantis was scheduled to roar into orbit in the early hours of 1 March. At the time of Columbia’s destruction, she was in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), having been rolled over from the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) on 29 January to be mated to her External Tank (ET) and twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), and only days away from rollout to Pad 39B.

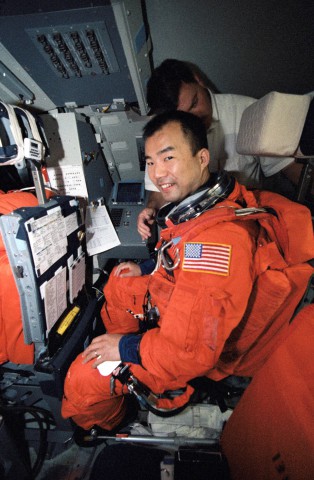

The seven astronauts and cosmonauts scheduled to fly uphill on STS-114 had been assigned at separate points throughout 2001. In March, U.S. astronaut Ed Lu, “along with a Russian commander and flight engineer,” were assigned to Expedition 7, who would be delivered to the ISS aboard the shuttle for a four-month tour of duty. A few weeks later, in April, Soichi Noguchi was assigned as a Mission Specialist for what was then designated “STS-113” and expected to fly aboard Endeavour in July 2002, with the expectation that he would likely participate in two EVAs. “Among all tasks in the mission, I take EVA as my main assignment,” he told an audience in January 2003. “I’m assigned as EV1, the primary EVA crew member. I’m responsible for all phases of EVA from training to the specific operation procedures. I feel that I’m the one who is fully in charge of the EVA process from the beginning, including training, to the end, through debriefing, after we’ve landed.”

By August 2001, when Collins, Kelly, Robinson, and the remainder of the Expedition 7 crew—Russian cosmonauts Yuri Malenchenko and Sergei Moschenko—were announced, the flight had been redesignated “STS-114” and scheduled for launch no sooner than November 2002. Delays to the shuttle fleet throughout the summer of the following year pushed STS-114 into the spring of 2003, and the mission eventually settled on a target of 1 March. (However, in the days preceding the loss of Columbia, NASA received Eastern Range approval for a launch attempt on 6 March.) Assuming an on-time liftoff, Atlantis would have docked at the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2 interface—which was then situated at the forward end of the U.S. Destiny laboratory module—on Flight Day Three and the STS-114 and Expedition 7 crews would have joined the incumbent Expedition 6 crew of U.S. astronauts Ken Bowersox and Don Pettit and Russian cosmonaut Nikolai Budarin. Shortly thereafter, Jim Kelly would have used the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm to remove the Raffaello MPLM from the shuttle’s payload bay and berth it onto the Unity node, allowing for the removal of equipment and supplies and three new research racks.

Three EVAs by Noguchi and Robinson were planned for the fifth, seventh, and ninth days of the mission, one of whose key tasks was the installation of the second External Stowage Platform (ESP-2)—to be situated on the station’s Quest airlock by means of an ESP Attachment Device (ESPAD)—which would provide eight Flight Releasable Attach Mechanisms (FRAMs) to accommodate Orbital Replacement Units (ORUs). Measuring 8.5 x 14 feet (2.6 x 4.2 meters), ESP-2 would be powered by the Unity node and installed by means of the spacewalkers and Kelly on the RMS. An additional core task was the removal and replacement of one of four 620-pound (280-kg) Control Moment Gyroscopes (CMGs) on the station’s Z-1 truss, which had experienced a failure in June 2002.

Returning to Earth after 12 days, STS-114 would be brought the Expedition 6 crew back home to their families and left the Expedition 7 team aboard the ISS through July 2003. However, the Expedition 7 crew had changed since their initial assignment. In October 2002, a request was made to the Multilateral Crew Operations Panel (MCOP) to replace “rookie” cosmonaut Sergei Moschenko with his backup, veteran cosmonaut Aleksandr Kaleri, and the change was formally announced by NASA in December. Certainly, training images of the STS-114 and Expedition 7 crews from November 2002 included Kaleri.

During their time aboard the ISS, the Expedition 7 crew would have been visited by two more shuttle crews, in May and July, and by Soyuz TMA-2 in April. The latter would have launched on 26 April from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, carrying Russian cosmonaut Gennadi Padalka and European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Pedro Duque of Spain, and was tasked with exchanging the Soyuz emergency crew return vehicles at the station. Padalka and Duque would have returned to Earth after about 10 days, aboard Soyuz TMA-1, which had been in residence since October 2002, and would have left the “fresh” Soyuz TMA-2 for Malenchenko, Kaleri, and Lu. It was also possible that the third seat aboard Soyuz TMA-2 would have been occupied, either by Russian cosmonaut Oleg Kotov or perhaps by Klaus von Storch, who might have become Chile’s first spacefarer. However, neither Kotov or von Storch had been confirmed for flight at the time of Columbia’s loss and it remained possible that the third seat volume may have been used for cargo.

A month later, on 23 May, Endeavour was scheduled to launch on her 10-day STS-115 mission, to continue the construction of the ISS. In fact, 2003 was intended to mark the most significant expansion of the station to date, with no fewer than 24 EVAs—18 from the shuttle and six by ISS crew members—planned to install ITS hardware, solar arrays, and power generation systems, thereby increasing the length of the truss from 134 feet (40.8 meters) to 310 feet (94.5 meters). It would be the third consecutive year to set a single-year world record for the number of spacewalks, eclipsing the 23 EVAs conducted in 2002 and the 18 EVAs performed in 2001. “Electricity-generating systems will almost triple in capacity during the next 12 months,” NASA revealed in December 2002. “The station crew faces a unique challenge, while almost continuously rewiring their orbiting home and laboratory, the electrical work must be done with virtually all household appliances and computers continuously running without interruption.”

In total, more than 80,000 pounds (36,200 kg) of hardware would have been delivered to the ISS in 2003, beginning with the P-3 and P-4 truss package aboard Shuttle Endeavour on STS-115, which included an enormous set of electricity-generating arrays. At the time of Columbia’s loss, Endeavour was in the OPF, undergoing post-flight checkout in the aftermath of her STS-113 mission, which had landed on 7 December 2002. Her three Auxiliary Power Units (APUs) had been replaced and exhaust duct leak checks were in work during the week prior to the tragedy. At the same time, technicians were preparing to remove her starboard Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pod for attention.

Led by Commander Brent Jett and Pilot Chris Ferguson, the STS-115 crew had been named in February 2002 and also included Mission Specialists Joe Tanner, Dan Burbank, Steve MacLean of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper, who would have supported no fewer than four EVAs in two teams to install and activate the new hardware on the port side of the ISS. A similar task would have awaited Endeavour’s next crew, on STS-117, planned for a 2 October liftoff, which would also have featured four EVAs to install the S-3 and S-4 truss package on the starboard side of the station. Announced a year earlier, in August 2002, the STS-117 crew consisted of Commander Rick Sturckow, Pilot Mark Polansky, and Mission Specialists Pat Forrester, Rick Mastracchio, Joan Higginbotham, and Jim Reilly.

The two shuttle missions alone would thus have delivered two sets of solar arrays with a combined surface area of 6,300 square feet (585 square meters) and a total of 65,000 individual power cells. Yet with four sets to be installed in total—one of which (the P-6 segment) was already aboard the ISS, but temporarily located atop the Z-1 truss—the presence of two additional “spacers” was necessary. The first of these spacers, designated “P-5” and nicknamed “Puny,” was to be launched aboard Atlantis on STS-116 on 24 July 2003, with the second, designated “S-5” and nicknamed “Stubby,” expected to follow aboard Columbia on STS-118 on 13 November. The latter would have marked Columbia’s next flight after STS-107 and, but for a cruel twist of fate, would have been her very first visit to the space station.

The first of these crews, STS-116, was a 10-day crew-rotation mission and would have seen the exchange of Expedition 7 for the incoming Expedition 8 team of U.S. astronauts Mike Foale and Bill McArthur and Russian cosmonaut Valeri Tokarev. The “core” shuttle crew, meanwhile, consisted of Commander Terry Wilcutt, Pilot Bill Oefelein, Mission Specialist Bob Curbeam, and ESA astronaut Christer Fuglesang of Sweden. During the flight, four EVAs would have been conducted to install and activate the P-5 truss and electrically reconfigure a large proportion of the ISS.

Late in the year, Soyuz TMA-3 would have flown from Baikonur to exchange emergency crew return provisions for the Expedition 8 crew, with launch anticipated on 18 October. The crew was officially listed as To Be Determined (TBD), although it has been suggested that possible members might have included Russian cosmonauts Vladimir Dezhurov and Oleg Skripochka, together with ESA astronaut Andre Kuipers of the Netherlands. These crew exchanges throughout 2003 would have enabled three expedition crews to have supported a total of 30 discrete experiments in biology, physics, chemistry, ecology, medicine, and manufacturing, as well as the effects of microgravity on the human body.

The final shuttle mission of 2003, Columbia’s STS-118 flight in November, would have featured three EVAs and extensive robotics operations by its crew of Commander Scott Kelly, Pilot Charlie Hobaugh, and Mission Specialists Scott Parazynski, Lisa Nowak, Barbara Morgan, and Canadian astronaut Dave Williams. When this crew was announced in December 2002, just a few weeks before the loss of Columbia, the presence of Morgan was notable, for she had originally been selected almost two decades earlier as the backup to Christa McAuliffe for the Teacher in Space Project (TISP). Subsequently chosen and trained as a fully-fledged Mission Specialist candidate, Morgan would become NASA’s first official “Educator Astronaut.”

“NASA has a responsibility to cultivate a new generation of scientists and engineers,” explained Administrator Sean O’Keefe in announcing Morgan’s selection. “Education has always been a part of NASA’s mission, but we have renewed our commitment to get students excited about science and mathematics. The Educator Astronaut program will use our unique position in space to help advance our nation’s education goals.” That renewal was pressed yet further in the days and weeks preceding the loss of Columbia. On 21 January 2003, O’Keefe and Florida First Lady Columba Bush outlined plans to expand the program with more Educator Astronaut applications to be accepted until 30 April. Within days—and whilst the STS-107 crew was still in orbit—more than 600 teachers had been nominated by students, family members, friends, and members of the public, a number which grew substantially to over 1,300 on the eve of the disaster and continued to climb in its aftermath, hitting 4,500 by the end of February.

In addition to transforming the physical appearance and capabilities of the ISS, the year 2003 would have been an impressive one for the annals of human space exploration. More EVAs would have been performed in a single calendar year than in any previous year in history. As many as 48 astronauts and cosmonauts—counting those lost aboard Columbia—might have ventured into space, including the first Israeli astronaut, the first Swedish astronaut and spacewalker, the first British-born commander of the space station, the second and third Canadian spacewalkers, the first Educator Astronaut, and perhaps the first Chilean astronaut.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Don Pettit, Fourth Most Experienced U.S. Astronaut, Turns 60 Today « AmericaSpace