Though three decades have passed, January 1986 has become entrenched in humanity’s popular consciousness as one of the darkest months in space history, for on its 28th day the crew of Challenger were lost in the skies of Cape Canaveral. The disaster would bring the space shuttle program to its knees for almost three years, but earlier in January 1986 another team of astronauts—the crew of Mission 61C, aboard Columbia—had narrowly missed a meeting with their maker. Their flight had been postponed since before Christmas 1985, and one of the astronauts was the unlucky Steve Hawley, who had endured the first shuttle pad abort a year earlier. His NASA crewmates were Robert “Hoot” Gibson in command, joined by Pilot Charlie Bolden and Mission Specialists George “Pinky” Nelson and Costa Rica-born Franklin Chang-Diaz. They would also be joined by a pair of Payload Specialists, whose identities remained in flux until shortly before launch.

Originally scheduled to fly in August 1985, they were meant to deploy two communications satellites—ASC-1 for the American Satellite Company and Syncom 4-4 for the U.S. Navy—and operate a Materials Science Laboratory (MSL-2) in the payload bay. However, by March 1985 their mission slipped into January 1986 and was redesignated 51L. In their “new” incarnation, the astronauts would deploy a large Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) for NASA and the Spartan-203 free-flier to observe Halley’s Comet. Then, in July 1985, they received the new designation of 61C, gained two other communications satellites, and picked up Payload Specialist Bob Cenker from the Radio Corporation of America (RCA).

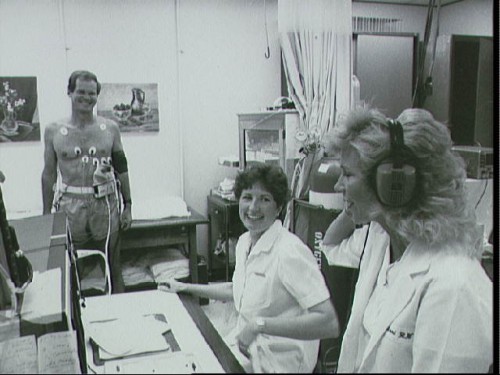

Cenker was an electrical and aerospace engineer who served as a senior staff engineer with RCA Astro Electronics (subsequently purchased by General Electric in 1986 to become GE AstroSpace) and had worked extensively on several communications satellite programs. In July 1983, RCA Astro Electronics received a $120 million contract from its sister company, RCA American Communications, to build three high-powered Satcom satellites for TV broadcasts. Two of these were to be launched late in 1985, with the third in 1987. Known as “Satcom-Ks” (or “Satcom-Kus”), each was capable of broadcasting in the 12-14 GHz Ku-band. Since Ku-band frequencies were not shared with terrestrial microwave systems, dishes served by the Satcoms could be located in major metropolitan areas.

For Cenker, who had served as RCA’s manager of systems engineering for the Satcom-K, it was “his” satellite and his technical responsibility. RCA paid NASA $14.2 million to launch Satcom K-1 on Mission 61C, and the satellite’s 16 transponders were expected to provide coverage of the entire contiguous United States. Confusingly, the second Satcom-K (“K-2”) was launched aboard Mission 61B, before K-1, and physically the satellites differed from many of their predecessors, in that they were cube-shaped, carried wing-like solar arrays, and were much heavier. In fact, at more than 4,200 pounds (1,900 kg), the Satcom-Ks were several times heavier than most other commercial communications satellites previously deployed by the shuttle. This demanded a more powerful version of McDonnell Douglas’ Payload Assist Module (PAM) booster. Enter the new PAM-D2, which could accommodate heavier payloads measuring up to 10 feet (3.3 meters) in diameter, as opposed to just over six feet (1.8 meters) for its predecessor, the PAM-D.

The second Payload Specialist on 61C should have been Greg Jarvis, a Hughes engineer, selected by his company in the summer of 1984 and first attached to Dan Brandenstein’s Mission 51D. Unfortunately for Jarvis, as the shuttle manifest shifted in early 1985, he moved further and further downstream. Since Hughes had built the Navy’s Syncom, it seemed likely that he would accompany one of those satellites into orbit, and he was earmarked to fly on Mission 51I for a while, before inexplicably disappearing from the crew roster and winding up on 61C. Then, in the autumn of 1985, Jarvis was moved again—this time to tragic Mission 51L. His place on 61C would be taken by Congressman Bill Nelson, a Democrat from Florida, and this reassignment—to a mission which did not even have a Hughes payload aboard—reinforced to many the reality that he had been moved simply to make room for a politician to fly.

“Willie Nelson,” as NASA’s then-Chief Astronaut John Young called him—“the one who can’t sing!”—had practiced law and served as an Army reservist before entering the Florida House of Representatives in 1972. He won re-election in 1974 and 1976 and served in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C., from 1978 until 1991. At the time of Mission 61C, Nelson chaired the House’s Space Science and Technology Subcommittee. Today a senior senator for Florida, he has proven a staunch supporter of NASA over the years and one of the agency’s most vocal political champions.

However, Nelson’s assignment brought with it the inevitable question of what he should do in orbit. Photography seemed the most obvious option, although Nelson wanted to be assigned something more important. Principal investigators would spend many years, and in some cases many millions of dollars, preparing their experiments for flight and training the astronauts to operate them, and they were reluctant to have a non-technical politician step in at the last minute and possibly screw them up. Commander Robert “Hoot” Gibson remained firm: the career Mission Specialists would operate the experiments. Some astronauts jokingly wondered if Nelson’s “important” experiment was to find a cure for cancer. In all sincerity, Nelson proposed that he take photographs of Africa to aid with the humanitarian effort. He also suggested a communications link between the shuttle and the cosmonauts aboard the Salyut 7 space station. Hearing of Nelson’s three “missions”—curing cancer, ending famine, and fostering better U.S.–Soviet relations—the Astronaut Office humorists quickly got in on the act, as noted by astronaut Mike Mullane in his 2006 memoir, Riding Rockets.

“Do you know how to ruin Nelson’s entire mission?” began the joke.

The response: “On launch morning, tell him they’ve found a cure for cancer, it’s raining a flood in Ethiopia and the Berlin Wall is coming down! He’ll be crushed!”

Yet, as a crew member, Nelson proved a model payload specialist. “He worked very hard,” admitted George “Pinky” Nelson. “Physically, he was in better shape than we were! He had no experience … in aviation or anything technical. He was a lawyer, but that didn’t stop him from trying, and I think he knew where his limitations were.” Though unrelated, the Nelsons became the first two men with the same surname to fly together in space.

Assigned to fly right-seat on Columbia’s flight deck, in the pilot’s position, Charlie Bolden—today serving as NASA Administrator—would credit Gibson with having taught him a great deal about shuttle systems and aerodynamics … and, most significantly, Hoot’s Law. By his own admission, Bolden struggled through his first few months of mission-specific training. “I really wanted to impress everybody on the crew and the training team,” he told the NASA oral historian. One day, in the simulator, the instructors threw a Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME) failure at the crew and, to distract them, quickly piled on more problems. Bolden followed his procedures, safing the engine, and was quickly presented with a minor glitch in an electrical bus.

His attention shifted to the new problem, but he picked the wrong bus and inadvertently shut down the bus for an operating engine. “When I did that,” he said, “the engine lost power and it got real quiet! We went from having one engine down in the orbiter, which we could’ve gotten out of, to having two engines down, and we were in the water, dead.” Bolden felt awful. If this ascent simulation had been for real, he would have brought death to them all in a feared Loss of Crew and Vehicle (LOCV) incident. Gibson, in his infinite wisdom, reached across the cockpit and patted Bolden on the shoulder.

“Charlie,” he said, “let me tell you about Hoot’s Law.”

“What’s Hoot’s Law?”

“No matter how bad things get, you can always make them worse!”

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

I met Bob Cenker at the Cape two years back. I wish I had been able to read this article before that luncheon, very informative.