Walt Cunningham, last surviving member of Apollo 7—the first manned orbital voyage of Project Apollo—died on Tuesday, 3 January. He was 90.

“Walt Cunningham was a fighter pilot, physicist and an entrepreneur, but above all, he was an explorer,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “On Apollo 7, the first launch of a crewed Apollo mission, Walt and his crewmates made history, paving the way for the Artemis Generation we see today.”

Ronnie Walter Cunningham was born on 16 March 1932 in Creston, Iowa, and despite a military background came to be seen—a tad derogatively—as one of “the scientists” of NASA’s early Astronaut Corps, owing to his impressive credentials as a civilian physicist. He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1960 and 1961, then commenced doctoral research, which he completed, apart from his final thesis.

By this stage, however, he had also served in the military. Cunningham joined the U.S. Navy in 1951 and began flight training whilst on active duty, then transitioned to reserve status with the U.S. Marine Corps. His rationale: in the Navy, pilots ran the risk of getting themselves assigned to torpedo bombers or heavy transport aircraft, whilst the Marines guaranteed him a spot flying much more glamorous single-engine fighters.

Before his selection by NASA in October 1963, Cunningham worked for the RAND Corp., performing research in support of classified programs and magnetospheric physics. “I was working on defense against submarine-launched ballistic missiles, trying to write in…the crudest fashion the equations that would intercept a missile on the rise,” he said later.

“At the same time, I was doing my doctoral work on the Earth’s magnetosphere,” Cunningham added. “It was a triaxial search coil magnetometer and we were trying to measure fluctuations in the Earth’s magnetic field.

“It was during this period that I applied and got accepted at NASA,” Cunningham continued. “I never did finish the thesis.”

With a self-confessed air of academia and irreverence to authority, Cunningham stood out among the 14 newbies selected as NASA’s third class of astronauts in October 1963, whose ranks included future Moonwalkers Buzz Aldrin, Dave Scott and Gene Cernan. In September 1966, he was assigned with astronauts Wally Schirra and Donn Eisele to Apollo 2, the second manned mission of the program, which NASA described as “an open-end, Earth-orbital mission of up to 14 days”.

In its original incarnation, Apollo 2 was a virtual repeat of the Apollo 1 test flight—using the first-generation “Block 1” Command and Service Module (CSM)—which astronauts Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee were expected to fly sometime in the first quarter of 1967. But Schirra deemed it senseless to repeat a mission already flown and by mid-November 1966 Apollo 2 was formally deleted from the flight manifest.

Instead, Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham were assigned as backups to Apollo 1, with no firm mission of their own on the horizon. But all that changed on the dreadful evening of 27 January 1967, when Grissom, White and Chaffee were killed as a fire swept through their Block 1 CSM during a “plugs-out” communications test atop their Saturn IB launch vehicle on Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy, Fla.

The tragic result was that by the late spring of 1967, as NASA and its contractor teams began the laboriously difficult process of rebuilding shattered dreams and creating an Apollo spacecraft that could someday reach the Moon, Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham—in a manner none of them could ever have wanted or wished—were assigned to Apollo 7, the first crewed mission of the program, targeted for late the following year. Their assignment was announced before Congress on 9 May by NASA Administrator Jim Webb.

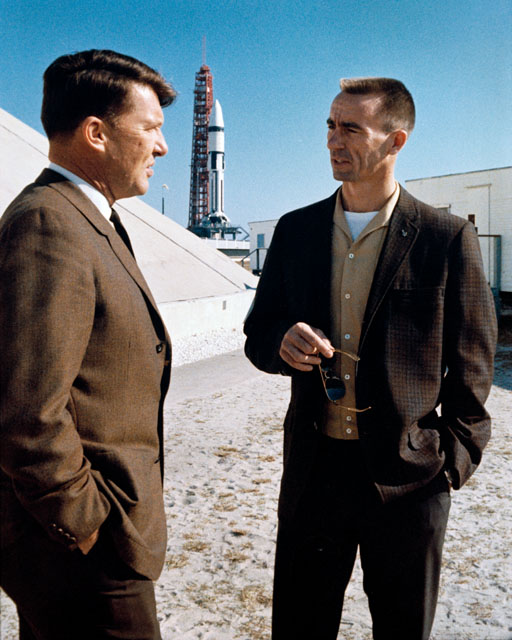

Early on 11 October 1968, the three men boarded Apollo 7 for an uneventful countdown, interrupted only briefly when the ventilator in Cunningham’s space suit acted up and began losing pressure; the ventilator was swapped for a spare with no further incident. Standing on Pad 34’s swing-arm, before ingressing the spacecraft, he had chance to look at the enormous Saturn IB.

“It was quite windy now,” Cunningham wrote in his memoir, The All-American Boys. “Beneath us, we could feel the vehicle and swing-arm sway.”

Apollo 7 took flight at 11:02 a.m. EDT, the Saturn IB’s eight H-1 first-stage engines punching out 1.6 million pounds (725,000 kilograms) of thrust, all under the watchful gaze of an estimated half-million spectators and 600 accredited journalists crowded along Florida’s roadways and beaches.

Cunningham’s first view of the Home Planet from space—a gorgeous sweeping vista of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula—was electrifying. “Just as it had appeared in drawings of the recent Arab-Israeli War, with the Suez Canal and the Red Sea on one side and the Gulf of Aqaba on the other,” he later wrote. “Here I was, looking at the globe as it really was.”

Apollo 7 would last just shy of 11 days, making it the United States’ second-longest manned space mission in history at that time. Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham performed rendezvous tests with the S-IVB final stage of their launch vehicle—just as future crews would do when picking up their Lunar Module (LM)—and successfully test-fired the large Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine at the base of the Service Module.

The trio also became unexpected media sensations, thanks to the “Wally, Walt and Donn Shows”, their regular telecasts from space—“from the lovely Apollo room, high above everything”—which later won them a special Emmy Award. But the astronauts also fell foul to severe head-colds, which reportedly caused irritation and a measure of friction with the personnel in Mission Control. By splashdown day, 22 October, their colds were so bad that Schirra refused to wear helmets during descent.

Many observers have ascribed this “insubordination” and identified the crew’s action as a pivotal factor in preventing Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham from flying again. Indeed, the former pair retired from NASA shortly after the mission, but Cunningham remained, later heading up the Skylab Branch of the Astronaut Office.

During this time, he worked extensively on the transition of America’s first space station from a “wet workshop”, utilizing a passivated rocket stage as a makeshift orbital home and laboratory, into a “dry workshop”, fully built and outfitted on the ground. But Cunningham had, it seemed, been “tarred and feathered” in the minds of many senior flight directors (including Chris Kraft) after Apollo 7, and when it became clear that he would not get a Skylab flight assignment he left NASA in August 1971.

In the aftermath of his astronaut career, Cunningham led multiple technical and financial organizations, serving in key leadership roles with Century Development Corp., Hydrotech Development Company and 3D International. He was also an investor and entrepreneur and a frequent keynote speaker and radio talk show host.

“We would like to express our immense pride in the life that he lived, and our deep gratitude for the man that he was—a patriot, an explorer, pilot, astronaut, husband, brother and father,” said the Cunningham family in a statement. “The world has lost another true hero and we will miss him dearly.”

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » Apollo »