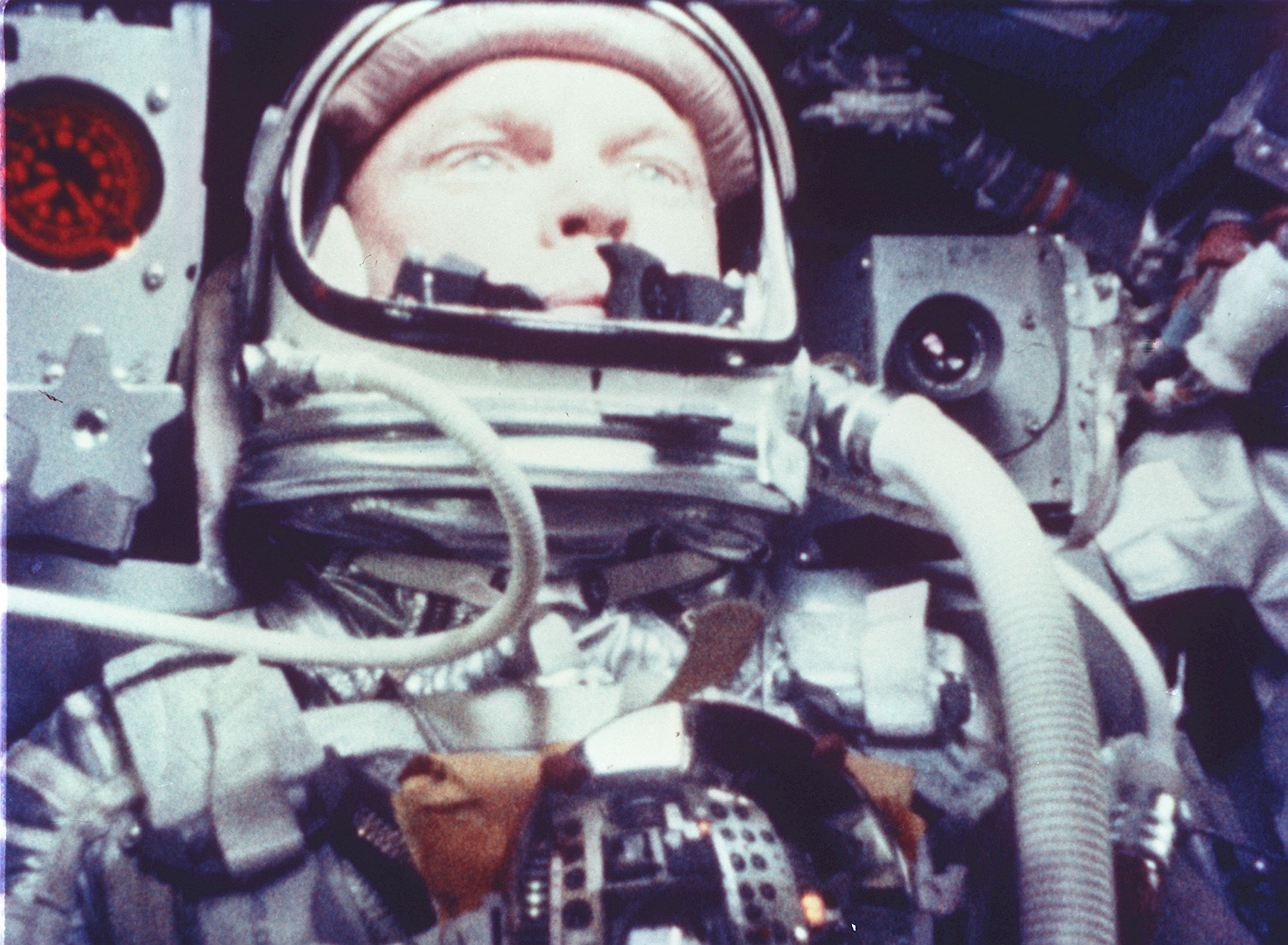

Two months after his death, aged 95, Monday will be a somber date for America’s human space program, as the 55th anniversary of John Glenn’s pioneering flight aboard Friendship 7—during which he became the first U.S. citizen in history to orbit the globe—passes without him. Glenn’s four hours and 55 minutes spent inside that tiny Mercury capsule, all those years ago, galvanized a generation into pushing ahead with President John F. Kennedy’s goal to land a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. And yet Glenn’s mission on 20 February 1962 was a truly hazardous undertaking and, but for several twists and turns of exceptionally good fortune, could easily have cost the astronaut his life.

By the dawn of the year, two Americans had launched into space. Al Shepard and Virgil “Gus” Grissom had launched in May and July 1961, atop converted Redstone missiles and had each completed a 15-minute suborbital “hop”. Despite the national success of achieving human spaceflight, both voyages paled in comparison to the Soviet Union’s first two piloted Vostoks, during which Yuri Gagarin circled Earth in April 1961 and Gherman Titov spent a day in orbit the following August. In fact, it was Titov’s mission which intensified the urgency to “get America orbital” as soon as possible, transitioning from Mercury-Redstone to the more powerful Mercury-Atlas launch architecture.

Originally scheduled to fly in December 1961, Glenn and his backup, fellow astronaut Scott Carpenter, found the mission postponed to January of the following year, due to minor technical troubles. In keeping with Project Mercury tradition, Glenn named his spacecraft “Friendship 7”, drawing inspiration from his children, Dave and Lyn, and he asked NASA artist Cecilia Bibby to inscribe the lettering in script-like characters. In doing so, Bibby became the only woman to ascend the gantry of Pad 14 at Cape Canaveral—and was even admonished, brusquely, by pad leader Guenter Wendt that she did not belong there. Glenn was so pleased with her stencil work that Gus Grissom dared Bibby to secretly paint naked on the spacecraft, too. She rose to the challenge and drew a naked woman on the inside of a cap used to cover Friendship 7’s periscope.

It would, she hoped, be seen by Glenn as he boarded his spacecraft on launch day. As circumstances transpired, Glenn loved it, but Bibby almost got fired for the practical joke. Only the intervention of Glenn and Gus Grissom saved her.

More delays afflicted Friendship 7 in early 1962, as technical issues and poor weather pushed the mission from mid-January to the second half of February. On the morning of the 20th, Glenn was awakened to a gloomy 50-50 weather forecast and proceeded through suiting-up for his flight. By 7 a.m. EST, he was alone, strapped atop the Atlas and, remarkably—in view of the booster’s lukewarm success record—his pulse varied from 60-80 beats per minute. “I could hear the sound of pipes whining below me as the liquid oxygen flowed into the tanks and heard a vibrant hissing noise,” he said later. “The Atlas is so tall that it sways slightly in heavy gusts of wind and. In fact, I could set the whole structure to rocking a bit by moving back and forth in the couch!”

Thirty-five minutes before launch, the rocket’s liquid oxygen supply was topped off and, despite another brief hold caused by a stuck fuel pump outlet valve and a last-minute electrical power failure at the Bermuda tracking station, the clock resumed ticking. With 18 seconds to go, the countdown reverted to automatic and, at four seconds, Glenn “felt, rather than heard” the engines roaring to life far below. At 9:47:39 a.m. EST, with a thunderous racket that overwhelmed Scott Carpenter’s call of “Godspeed, John Glenn”, the Atlas’ hold-down posts separated and the enormous rocket began to climb.

“The Atlas’ thrust was barely enough to overcome its weight,” he wrote in his autobiography, John Glenn: A Memoir. “I wasn’t really off until the umbilical cord that took electrical communications to the base of the rocket pulled loose. That was my last connection with Earth. It took the two boosters and the sustainer engine three seconds of fire and thunder to lift the thing that far. From where I sat, the rise seemed ponderous and stately, as if the rocket were an elephant trying to become a ballerina.” For the first few seconds, the Atlas climbed straight up, before its automatic guidance system placed it carefully onto a north-easterly heading; a transition which Glenn found noticeably “bumpy”. By 9:52 a.m.—barely five minutes after liftoff—the mission was “through the gates” and Glenn was heading smoothly towards low-Earth orbit.

Although he was able to describe the magnificent views he was seeing, it was on this mission that the rest of the world was also able to capture something of the grandeur of Earth, thanks to a camera. Months earlier, whilst getting a haircut in Cocoa Beach, Glenn saw a little Minolta camera in a display case. It had automatic exposure and he bought it for $45. NASA technicians adapted it for the spacecraft and Glenn found that it was the easiest camera to use, even wearing his pressure suit gloves. It would yield some of the most amazing images of the entire mission.

Achieving orbit on 20 February 1962, Glenn uttered the immortal words for which he would be most remembered. “Zero-G and I feel fine,” he exulted. “Capsule is turning around,” he added as Friendship 7 slowly swung around into the re-entry attitude. “Oh, that view is tremendous!” he exclaimed as the horizon appeared in the window and he caught his first sight of the curvature of the Earth and the fragile atmosphere.

Looking back, he clearly saw the spent Atlas making slow pirouettes as it tumbled away. At 9:59 a.m., he crossed the coast of western Africa—“a fast transatlantic flight”, he later wrote—and felt one of his earliest sensations of weightlessness: a gray-felt toy mouse drifted from an equipment pouch. After quickly checking his blood pressure for the Canaries ground station, Glenn turned his attention to photographing selected spots on Earth’s surface. Next came further checks of his attitude controls, which were “well within limits”, followed by exertion tests with a bungee cord attached beneath the instrument panel and then reading the vision chart at eye-level. Glenn’s vision, it seemed, was not changing. Head movements, too, did not cause him any disorientation.

Forty minutes into the mission, Friendship 7 drifted into darkness. A sunset from space was one of the features of the flight about which he was most excited. “Above” him, the sky was absolutely black, although he could see stars and identified the Pleiades cluster. Then, as Friendship 7 passed directly over Perth and Rockingham, in Australia, Capcom Gordo Cooper asked him if he could see lights. “I can see the outline of a town,” he replied, “and a very bright light just to the south of it.” Glenn thanked the residents of Perth for turning on their lights to greet him.

Travelling over the South Pacific, close to the tiny coral atoll of Canton Island, midway between Fiji and Hawaii, the astronaut lifted his visor and ate: squeezing some apple sauce from a toothpaste-like tube into his mouth and gobbling some malt tablets. As he approached orbital sunrise, Glenn was surprised to see around the capsule a huge field of particles, like thousands of swirling fireflies. “They were greenish-yellow in color,” he said later. “They were all around me and those nearest the capsule would occasionally move across the window, as if I had slightly interrupted their flow.” The particles diminished in number as he flew eastwards into brighter sunlight and were later attributed to ice crystals venting from Friendship 7’s heat exchanger.

Meanwhile, Glenn continued putting his capsule through its paces. It was shortly after passing the two-hour mark of the mission, however, that he received an odd request from Mercury Control: to keep the switch for Friendship 7’s landing bag in the Off position. He confirmed that the switch was indeed off and pressed on with his work. Later, Gordo Cooper asked him to confirm it again. Then, during another pass over Canton Island, Glenn overheard an indication from a flight controller that his landing bag—located between the base of the spacecraft and the heat shield—might have accidentally deployed. He was assured that the ground was monitoring the situation. Glenn began to suspect that the fireflies might be related to some shifting of his heat shield.

As early as the second orbit, telemetry engineer William Saunders noted that “Segment 51”—an instrument providing data on the landing system—was generating unusual readings, and Mercury Control instructed all tracking sites to monitor it carefully. A little over four hours into the flight, however, it became clear that the landing bag was either deployed or improperly locked into position. Whilst over Hawaii, the capcom informed Glenn that the signal was probably erroneous, but, to be sure, asked him to set the landing bag switch in its “auto” position.

“Now, for the first time, I knew why they had been asking about the landing bag,” Glenn wrote in his memoir. “They did think it might have been activated, meaning that the heat shield was unlatched. Nothing was flapping around. The package of retrorockets that would slow the capsule for re-entry was strapped over the heat shield. But it would jettison and what then? If the heat shield dropped out of place, I could be incinerated on re-entry.”

If the green landing bag light came on, it would clarify that it had indeed accidentally deployed. However, “if it hadn’t, and there was something wrong with the circuits, flipping the switch to automatic might create the disaster we had feared”.

He flipped the switch. No light came on.

This suggested that the landing bag was secure. As retrofire approached, Capcom Wally Schirra, based at Point Arguello in California, told Glenn not to jettison his retrorocket package at least throughout his passage across Texas. It marked the first of several efforts to ensure that, if the heat shield had been loosened, the retrorocket package might hold it in place just long enough to survive the hottest part of re-entry.

Six minutes before retrofire, Glenn duly maneuvered Friendship 7 into a 14-degree, nose-up attitude. At 2:20 p.m. EST, the first retrorocket fired, causing a dramatic braking effect on the capsule and making him feel momentarily as if he was flying backwards, towards Hawaii. The second and third retrorocket firings came at five-second intervals, slowing the capsule sufficiently to drop it out of orbit. Once again, Schirra repeated, “Keep your retro pack on until you pass Texas.”

The tension at Mission Control was palpable.

“I looked around the room,” wrote Procedures Officer Gene Kranz in his autobiography, Failure is Not an Option, “and saw faces drained of blood. John Glenn’s life was in peril.”

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace