Since July 1969, astronaut Mike Collins has achieved worldwide renown as “the other one” on the first lunar landing mission. But a year earlier, he might have been aboard Apollo 9, shoulder-to-shoulder with Frank Borman and Bill Anders, to perform a high-Earth-orbit test of the Command and Service Module (CSM) and Lunar Module (LM). That mission changed markedly by the time it eventually flew—redesignated“Apollo 8”, and with a very different destination—but for Collins the most significant change was that in a matter of weeks, he had gone from sitting in the Senior Pilot’s seat to sitting on the sidelines in Mission Control. It must have been a devastating blow, for 50 years ago, this month, the first humans in history set sail for another world.

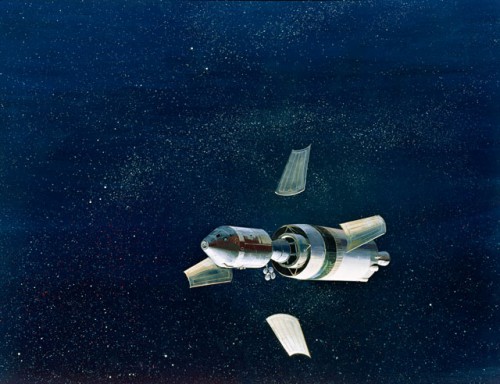

NASA’s original line-up for Apollo envisaged a seven-step process, labeled “A” to “G”. First would have come the unmanned test-flights (“A”) of the CSM, achieved by Apollo 4 in November 1967 and Apollo 6 in April 1968. Next, the “B” mission—completed by Apollo 5 in January 1968—would test the LM. A manned “C” flight, involving the CSM in low-Earth orbit, was executed by astronauts Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walt Cunningham in October 1968 and final strides focused on four increasingly more complex voyages: “D” (a manned demo of the entire spacecraft in low-Earth orbit), “E” (a repeat of D, albeit in a highly elliptical orbit around the Home Planet), “F” (a full dress-rehearsal in lunar orbit) and “G” (the landing itself).

It was to the E mission that Borman, Collins and Anders were assigned. By the end of 1967, an increased waveof optimism swept NASA that a manned lunar landing was possible before the decade’s end. And in August 1968, senior managers provisionally decided to expedite Borman’smission from a highly elliptical Earth-orbital flight—with an estimated apogeeof 4,000 miles (6,400 km)—to a full circumnavigation of the Moon, the furthest voyage ever undertaken in human history. However, by this time, Collins was already gone from the crew. In July 1968, whilst playing handball, he noticed that his knees buckled when he walked down stairs, accompanied by a peculiar tingling and numbness. A neurologist diagnosed a bony growth between his fifth and sixth vertebrae, which was pushing against his spinal column, with surgery deemed the only option. The procedure went well, but Collins lost his seat on the lunar mission to his backup, veteran astronaut Jim Lovell.

By this time, the layout of missions had also changed. Delays in the development of the LM—a critical element of the D mission—caused it to move back to Apollo 9 and Borman’s flight was correspondingly brought forward to Apollo 8. The flight was redesignated “C-Prime”, with an expectation that the crew would test-fire the spacecraft’s Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine during their translunar coast. If it failed to work properly, Apollo 8’s free-return trajectory would still enable them to loop around the Moon and come safely back to Earth without the SPS. But Borman had other worries. The six-day flight was targeted to splashdown in the Pacific Ocean and, to do so in daylight would require at least 12 lunar orbits, two more than were on the flight plan. Borman could not care if he landed in daylight or darkness. “Frank didn’t want to spend any more time in lunar orbit than was absolutely necessary,” wrote Deke Slayton, head of Flight Crew Operations at the time, “and pushed for—and got—approval of a splashdown in the early morning, before dawn.” Apollo 8 would do ten orbits of the Moon.

To understand Borman’s reluctance to do more than was necessary is to understand part of his character and military bearing: he was wholly committed to “The Mission”, whatever it might be. On Apollo 8, that mission was to reach the Moon and bring his crew home safely. Nothing else mattered. All non-essential requests irritated him. “Some idiot had the idea that on the wayto the Moon, we’d do an EVA,” he recounted years later in a NASA oral history. “What do you want to do? What’s the main objective? The main objective was togo to the Moon, do enough orbits so that they could do the tracking, be the pathfinders for Apollo 11 and get your ass home. Why complicate it?”

The four months leading up to the mission were conducted at a break-neck pace. The lunar launch window opened on 21 December 1968, at which time Mare Tranquillitatis (the Sea of Tranquillity, a low, relatively flat plain tipped as a possible first landing site) would be experiencing lunar sunrise and its landscape would be thrown into stark relief, allowing Borman, Lovell and Anders to photograph it. In the final six weeks before launch, the crew regularly put in ten-hour workdays, with weekends existing only to wade through piles of mail. At the end of November, outgoing President Lyndon Johnson threw them a bon voyage partyin Washington, D.C. Then, on the evening of 20 December, the legendary Charles Lindbergh—first to fly solo across the Atlantic—visited their quarters at Cape Kennedy, Fla. During their meal, the topic of conversation turned to the Saturn V rocket, which would burn nearly 40,000 pounds (1,800 kg) of propellant in its first second of firing.

As quoted by Andrew Chaikin in his landmark book, A Man on the Moon, Lindbergh was astounded.

“In the first second of your flight tomorrow,” he told them, “you’ll burn ten times more fuel than I did all the way to Paris!”

Shortly after 2:30 a.m. EST on launch morning, 21 December 1968, Deke Slayton woke them in Cape Kennedy’s crew quarters and joined them for the ritual breakfast of steak and eggs. Also in attendance were Chief Astronaut Al Shepard and Apollo 8 backup crewmen Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin. (The third backup crew member, Fred Haise, was busily setting switch positions inside the command module at Pad 39A.) Shortly thereafter, clad in their snow-white spacesuits and bubble helmets, they arrived at the brilliantly floodlit pad, where their Saturn V awaited. First Borman, then Anders, and finally Lovell took their seats in the command module, joining Haise, who had by now finished his job of checking switches. After offering them his hand in solidarity and farewell, Haise crawled out of the cabin, and the heavy unified hatch slammed shut at 5:34 a.m.

Years later, Bill Anders told Andrew Chaikin that he glanced over at a window in the boost-protective cover and saw a hornet fluttering around outside. “She’s building a nest,” he thought, “and did she pick the wrong place to build it!”

As their 7:51 a.m. launch time drew closer, a sense of unreal calm pervaded Apollo 8’s cabin. With five minutes to go, the white room and its access arm rotated away from the spacecraft and, shortly thereafter, the launch pad’s automatic sequencer took charge of the countdown, monitoring the final topping-off of propellants needed by the Saturn V to reach space. Sixty seconds before launch the giant rocket was declared fully pressurized, and it transferred its systems to internal battery power as four of the nine servicing arms linking it to utilities on Pad 39A were disconnected.

“T-50 seconds and counting,” intoned public affairs commentator Jack King in the Launch Control Center. “We have the power transfer. We’re now on the flight batteries within the launch vehicle.”

The seconds ticked away.

At 17 seconds came the final alignment of the Saturn’s guidance computer, and it was transferred to internal power.

“T-15, 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, nine … ”

It was at this stage that the ignition sequence of the largest and most powerful rocket ever brought to operational status began and pressurized propellants flooded into the five F-1 engines on the Saturn’s first stage. Despite being cocooned inside their space suits, Borman, Lovell and Anders could faintly hear the sound of fuel pouring into the combustion chambers, 36 stories below them.

“We have ignition sequence start. The engines are armed…”

HaRd to believe it’s been 50 years. Also, part of the decision to go the the Moon on Apollo 8 was the possibility of the Soviets flying a 2-man ZoND to loop around the Moon in an early December launch window