When we think of heroes in the early Space Age, our minds are naturally drawn to the likes of Yuri Gagarin and Al Shepard, to Alexei Leonov and John Glenn, to Valentina Tereshkova and Neil Armstrong, and to Sergei Korolev and Wernher von Braun. These brave heroes, and thousands like them, charted our first course away from the Home Planet and—after millions of years of simply gazing upward and wondering—they enabled us to see new visions and visit new worlds. Their sacrifice and contribution remains incalculable, but one other man enabled the single step to be taken which may define us a thousand years from now. John Fitzgerald Kennedy, 35th President of the United States, killed in Dallas, Texas, 50 years ago today, was responsible for providing the political direction for America to land a man on the Moon. His actions, to be fair, were deep-rooted in the politics of his time, but their long-term effects have transformed him into a true hero of the Space Age.

Kennedy’s hideous murder remains one of the most dramatic, pervasive, and mysterious events of the 1960s, coming midway between the conclusion of Project Mercury and the dawn of Project Gemini. The president had been in Texas for several days and, tanned and wearing sunglasses, had visited and been photographed at NASA’s new Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), near Houston, in the days before his death. His decision to visit Dallas and tour the streets in an open-topped motorcade on 22 November 1963 had come about in the hope that it would generate support for his 1964 re-election campaign and mend political fences in a state just barely won three years before.

The plan called for Kennedy’s motorcade to travel from Love Field airport, through downtown Dallas—including Dealey Plaza, where the assassination would occur—and would terminate at the Dallas Trade Mart, where he would deliver a speech. Shortly before 12:30 p.m. CST, the motorcade entered Dealey Plaza and Kennedy acknowledged a comment from Nellie Connally, wife of the Texan governor, that “you can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you.” Indeed, all around him, adoring crowds thronged the streets.

As the motorcade passed the Texas School Book Depository, the first crack of a rifle sounded from one of its upper windows. There was very little reaction to the opening shot, with many witnesses believing that they had heard a firecracker or a backfiring engine. Kennedy and Governor John Connally turned abruptly, and it was Connally who first recognized the sound for what it was. Yet he had no time to respond. According to the Warren Commission, which investigated the case throughout 1964, a shot entered Kennedy’s upper back and exited through his throat, causing him to clench his fists to his neck. The same bullet hit Connally’s back, chest, right wrist, and left thigh.

The third and final shot, captured in horrifying detail by a number of professional and amateur photographers, caused a fist-sized hole to explode from the side of the president’s head, spraying the interior of the limousine and showering a motorcycle officer with blood and brain tissue. First Lady Jackie Kennedy frantically clambered onto the back of the limousine; Secret Service agent Clint Hill, close by, thought she was reaching for something, perhaps part of the president’s skull, and pushed her back into her seat. Hill kept Mrs. Kennedy seated and clung to the car as it raced away in the direction of Parkland Memorial Hospital.

John Connally, though critically injured, survived, but Kennedy arrived in the Parkland trauma room in a moribund condition and was declared dead by Dr. George Burkley at 1 p.m. No chance ever existed to save the president’s life, the third bullet having caused a fatal head wound. Indeed, a priest who administered the last rites told the New York Times that Kennedy was dead on arrival. An hour later, following a confrontation between Dallas police and Secret Service agents, the president’s body was removed from Parkland and driven to Air Force One, then flown to Washington, D.C. Vice-President Lyndon Baines Johnson, also aboard Air Force One, was sworn-in as the 36th President at 2:38 p.m.

One of Johnson’s earliest official acts was the establishment of the “Warren Commission” to investigate the president’s death. Chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren—the very man who had sworn Kennedy into office—the commission presented its report to Johnson in September 1964. It found no persuasive evidence of a domestic or foreign conspiracy and identified Lee Harvey Oswald, located on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, as the murderer. It concluded that both Oswald and his own killer, nightclub owner Jack Ruby, had operated alone and without external involvement.

Immediately after the publication of the Warren Commission’s report, doubts surfaced over its conclusions. Although initially greeted with widespread support by the public, a 1966 Gallup poll suggested that inconsistencies remained. An official investigation by the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1976-1979 concluded that Oswald probably shot Kennedy as part of a wider conspiracy and, over the years, countless theories have emerged, variously blaming Fidel Castro, the anti-Castro Cuban community, the Mafia, the FBI, the CIA, the masonic order, the Soviets, and others. An ABC News poll in 2003 concluded that 70 percent of respondents felt that the assassination was the part of a broader plot, although no agreement could be reached on who may have been involved. To this day, Kennedy’s death remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the modern era.

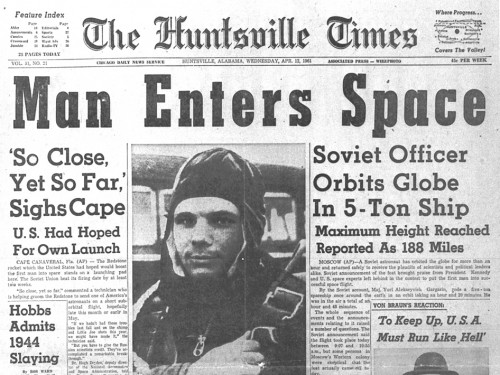

Sworn in as president on 20 January 1961, after a long-fought campaign with Richard Nixon, one of Kennedy’s immediate goals was to address a perceived “gap” in missile technology between the United States and the Soviet Union. Both nations were racing to place a man into space—America through Project Mercury and Russia through its Vostok program—and the stakes were high. The success of Yuri Gagarin’s orbital mission on 12 April left Kennedy with the urgent need to do something to restore his nation’s credibility and technological muscle. A suborbital Mercury flight was almost ready to go, but a fully orbital mission was not expected until at least the end of 1961, and a CIA-backed attempt by a group of Cuban exiles to topple Fidel Castro at the Bay of Pigs collapsed in catastrophic fashion and proved hugely embarrassing for the United States.

Although he admitted responsibility for the bungled invasion, on 20 April Kennedy refined his plans to draw the Soviets into a space race and perhaps gain more credibility for his government. “Is there any space program,” he asked Vice-President Lyndon Johnson in one of the 20th century’s most influential memos, “that promises dramatic results in which we could win? Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space or a trip around the Moon or by a rocket to land on the Moon or by a rocket to go to the Moon and back with a man?” His motives, of course, were chiefly political, but he was clearly pinning his colours to the space flag.

One of the main personalities approached by Johnson as he weighed up the options was the famed rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, who, in a 29 April memo, felt that the “sporting chance” of sending a three-man crew around the Moon before the Soviets was higher than putting an orbital laboratory aloft. Others, including Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, even pushed for a landing on Mars, although his motivations for such a proposal have been questioned. Von Braun, who had designed Nazi Germany’s infamous V-2 missile before coming to the United States in 1945 as a key player in its rocketry and space programs, felt that a lunar landing was the best option, since “a performance jump by a factor of ten over their present rockets is necessary to accomplish this feat. While today we do not have such a rocket, it is unlikely that the Soviets have it.”

The rocket to which von Braun alluded was known as “Saturn” and remained in the early planning stages, but a commitment to its development had been one of the conditions he had applied before agreeing to join NASA in October 1958. “With an all-out crash effort,” he told Johnson, “I think we could accomplish this objective in 1967-1968.” Von Braun’s judgement won the day for Johnson. Three weeks later, still smarting from Bay of Pigs humiliation, Kennedy delivered the speech which would truly define his presidency.

Several days later, on 5 May, Al Shepard became America’s first man in space, completing a 15-minute suborbital mission aboard Freedom 7, which Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev lambasted as a “flea hop” in comparison to Gagarin’s flight. In the aftermath, Kennedy wanted to talk of nothing but space, and some cynically speculated that his motivations centered upon beating the Soviets and overcoming the Bay of Pigs humiliation. However, when Shepard met the president shortly after the flight, he saw a true statesman and believed that the attraction of space exploration was very real for Kennedy. “He was really, really a space cadet,” Shepard told the NASA oral historian, many years later, “and it’s too bad he could not have lived to see his promise.” Three weeks after Freedom 7, Kennedy nailed his colors to the space mast in one of the most rousing and inspiring addresses ever given in U.S. political history.

On 25 May, the president stood before a joint session of Congress and publicly declared his vision. He knew, after recommendations from both NASA Administrator Jim Webb and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, that the presence of men in space would truly capture the imagination of the world. The first part of his speech focused upon ways in which the United States could exploit its economic and social progress against Communism, then called for increased funding to protect Americans from a possible nuclear strike … and lastly Kennedy hit Congress with his lunar bombshell. “I believe,” he told them, “that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period would be more impressive to mankind or more important for the long-range exploration of space … and none would be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Expense was the major stumbling block. By the end of 1961, NASA’s budget would grow to more than $5 billion, 10 times as much as had been spent on space research in the past eight years combined and roughly equivalent to 50 cents per taxpayer. Kennedy acknowledged that it was “a staggering sum,” but reinforced that most Americans spent more each week on cigars and cigarettes. Still, he would have to face harsh criticism by placing the lunar goal ahead of educational projects and other social welfare efforts for which he had campaigned so hard during his years in the Senate. He would admit in his speech that he “came to this conclusion with some reluctance” and that the nation would have to “bear the burdens” of the dream.

Some did not wish to accept such burdens. Immediately after the speech, a Gallup poll revealed that just 42 percent of Americans supported Kennedy’s push for the Moon. Yet he also gained immense support, both as a risk-taker and as a statesman. The decision, said his science advisor Jerome Wiesner, was one that he made “cold-bloodedly.” It was also a decision that he firmly stood by. Only hours after Virgil “Gus” Grissom flew America’s second suborbital mission on 21 July 1961, Kennedy signed into law an approximately $1.7 billion appropriation act for Project Apollo. In a subsequent address, given at Rice University in September 1962, he admitted that Apollo and Saturn would contain some components still awaiting invention, but remained fixed in his determination to “set sail on this new sea, because there is new knowledge to be gained and new rights to be won.”

The overall picture still seemed to show that Kennedy was broadly supportive of the lunar goal, although taped conversations with Jim Webb, now ensconced in the Kennedy Library, imply otherwise. In November 1962, at a meeting to discuss the space budget, Kennedy categorically told Webb that he was “not that interested in space” and that his stance in support of the program was based purely on the need to beat the Soviets. Nonetheless, he had approached Khrushchev on two occasions—in June 1961 and again in 1963—to discuss space co-operation; in the first case, his entreaties fell on deaf ears, but in the second case, the Soviet premier responded with greater warmth.

Still, there remained doubts in large swathes of the American populace about the lunar goal. In April 1963, Kennedy had asked Vice-President Lyndon Johnson—in his capacity as head of the National Aeronautics and Space Council—to review Project Apollo’s progress. “By asking Johnson to conduct the review, Kennedy was virtually assured of a positive reply,” wrote space policy analyst Dwayne Day in a November 2006 article for The Space Review. “Furthermore, Kennedy’s request in effect ruled out cutting Apollo so as not to ‘compromise the timetable for the first manned lunar landing.’” In his report, Johnson advised that, if cuts were to be made to NASA, they ought to be diverted to safeguard Apollo.

A few days after Kennedy’s speech to the United Nations in September 1963, Congressman Albert Thomas, chairman of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Independent Offices, wrote to the president and asked if he had altered his position on the lunar landing. Kennedy replied that the United States could only co-operate in space from a position of strength, but shortly before his assassination he asked the Bureau of Budget to prepare a report on NASA. A draft of this report, which addressed the question of “backing off from the manned lunar landing goal” was written in early 1964 and still exists. In his analysis, Day posited that this was the very question that Kennedy had asked them to consider. The bureau’s ultimate consensus: the only basis for backing off from Apollo, aside from technical or international situations, would be “an overriding fiscal decision.”

Throughout the Sixties, and long after Kennedy’s death, the road to the Moon remained fraught with danger and risk. Several astronauts lost their lives in training accidents, and the Apollo 1 crew died in a cabin fire during a “plugs-out” ground test in January 1967, putting the program on hold for almost two years. The pace at which the United States moved from suborbital missions in early 1961 to Earth-orbital rendezvous in 1965 to the first piloted voyage to the Moon in 1968 to the landing itself in 1969 remains one of the most phenomenal feats in the history of human accomplishment. Four percent of the federal budget, to be fair, had much to do with this pace, but it puts several of our subsequent efforts to return humans to the Moon to shame.

Twenty-four hours before the paths of the president and the assassin tragically intertwined, on 21 November 1963, Kennedy recounted a story to a San Antonio audience. Reminding them that it was still “a time for pathfinders and pioneers,” he told the tale of a group of Irish boys who reached an orchard wall and were dismayed that it was too tall to scale. Throwing their caps over the wall, they presented themselves with no choice but to force themselves to scale it. “This nation,” Kennedy told his rapt audience, “has tossed its cap over the wall of space and we have no choice but to follow it. Whatever the difficulties, they will be overcome.”

And six years after his death, they were. Today, on the half-century anniversary of Kennedy’s death, it can be hoped that the difficulties and challenges which lie before humanity today can be similarly overcome and a return of humans to the Moon, and perhaps also to Mars, can be accomplished in our lifetimes. Only then can we humans cement our credentials as a truly spacefaring civilization.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » Apollo »

Excellent Article Ben…But we could not recreate that Apollo Miracle today sadly as we were in the fight for our lives as the COLD WAR ramped up and it was decided at any cost we had to beat the Soviets to the Moon. In fact even after the clear and realized danger that an asteroid caused in Russia early this year…It was met with a collective yawn by the general public. Our country has become so corrupt that everybody wants everything from our government and they now have politicians in office that will give them that… Our only hope as a civilization is to create the ability through the private sector to colonize the Moon, Mars and beyond… We owe a great deal to JFK ..lets hope his sacrifice does not go in vain…

I seriously doubt that our brave sons and daughters serving our beloved America in the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, Coast Guard in Afghanistan and other extremely dangerous places on your behalf would find comfort in your statement that “our country has become so corrupt”. I love this great nation, and do not appreciate comments which deprecate the sacrifice of those who have given “that last full measure of devotion”. I believe our hope as a civilization is in heroic individuals of integrity like Shepard, Glenn and Armstrong. You, of course, are free to put your hope in Bernie Madoff.

Karol,

If the government was not corrupt Bernie Madoff would have been put in Jail 15 years ago when very specific and honest Wall Street fund managers contacted the SEC and told them point blank Bernie was getting impossible returns for his clients…The SEC did nothing and goes all the way back to the Clinton Administration…What has our Military become when they are used as toys of Global Monopoly Players such as the entire mess in Libya…If this is not government corruption what is? The Actions of Shepard, Glenn and Armstrong are heroic indeed and there will be new heroes that will meet the challenge but they will have to come from the Private Sector as the United States is collapsing as sure as the Roman Empire did…

So, apparently when that brave young Marine shoulders his weapon and risks his life to go out on patrol in Kandahar province, he is following the orders of a corrupt government and is one of the “toys of Global Monopoly Players?”

I’m very sorry AmericaSpace.

I have thoroughly enjoyed Americaspace. Thank you Jim, Jason, and Ben for the many hours of enjoyable, entertaining, and highly educational reading. Keep up the great work Leonidas my friend, your work shows great promise! Maybe I’ll see you at the Orion/SLS launch – I’ll be the one wearing the NASA cap! 🙂

Karol,

The soldier has no choice but to go where he is asked….Presently we are at the mercy of Corrupt Government Players as this article from Ben shows even killing presidents are not out of bounds… I do hope you make it to the Orion/SLS launch in Dec 2017 for Titos mission to Mars…

In an exceptional account of Kennedy’s decision to go to the Moon, Ben has included interesting details about how that momentous decision might have been reversed, something generally ignored in the general popular literature. How marvelous was Kennedy’s speech at Rice University when he stated “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” The right words at the right time in an era that inspired our nation to achieve greatness. Where or where has that kind of leadership gone?