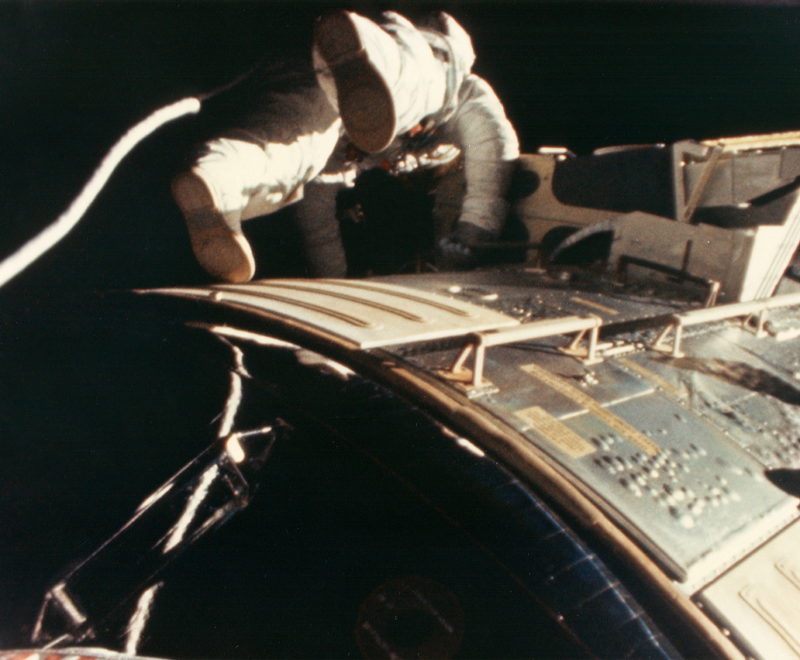

Fifty years ago today, a fully suited astronaut poked his helmeted head out the side hatch of the Command Module “Endeavour”, into an environment like no other. Al Worden, one of three crew members on Apollo 15—our first foray to the mountains of the Moon—was tasked with retrieving film and cameras from the Scientific Instrument Module Bay (SIMBay) of the Service Module (SM).

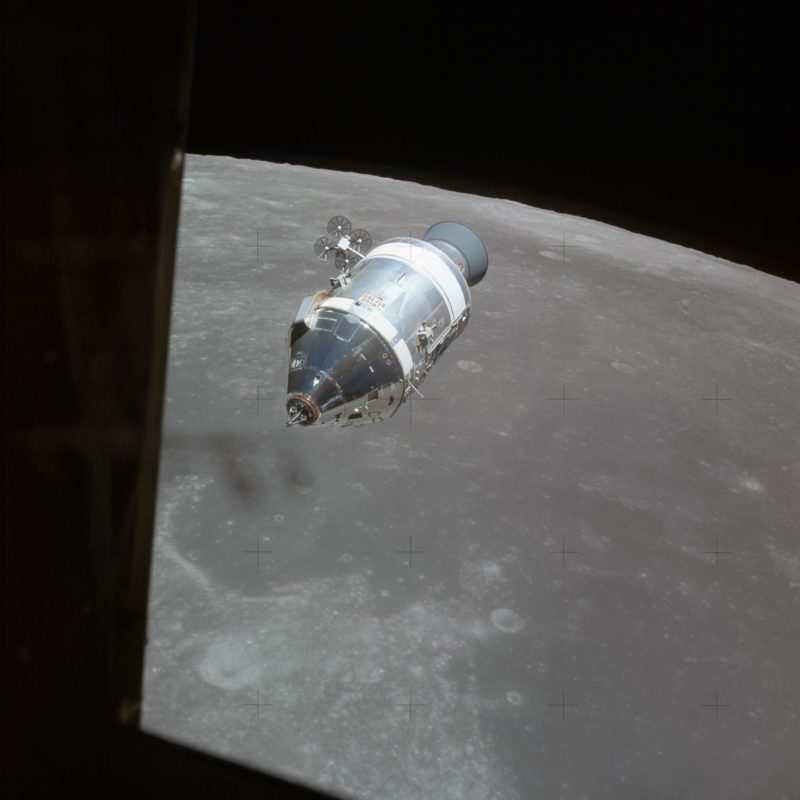

To do that, he was required to clamber, hand over hand, across a gulf of 30 feet (9 meters) and back again. Extravehicular Activity (EVA) had been performed several times by U.S. astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts by 5 August 1971, but with the exception of the Apollo Moonwalkers all had been done in low-Earth orbit. Worden remains one of only three men to have performed a “Deep Space EVA”, in the cislunar void between Earth and our closest celestial neighbor.

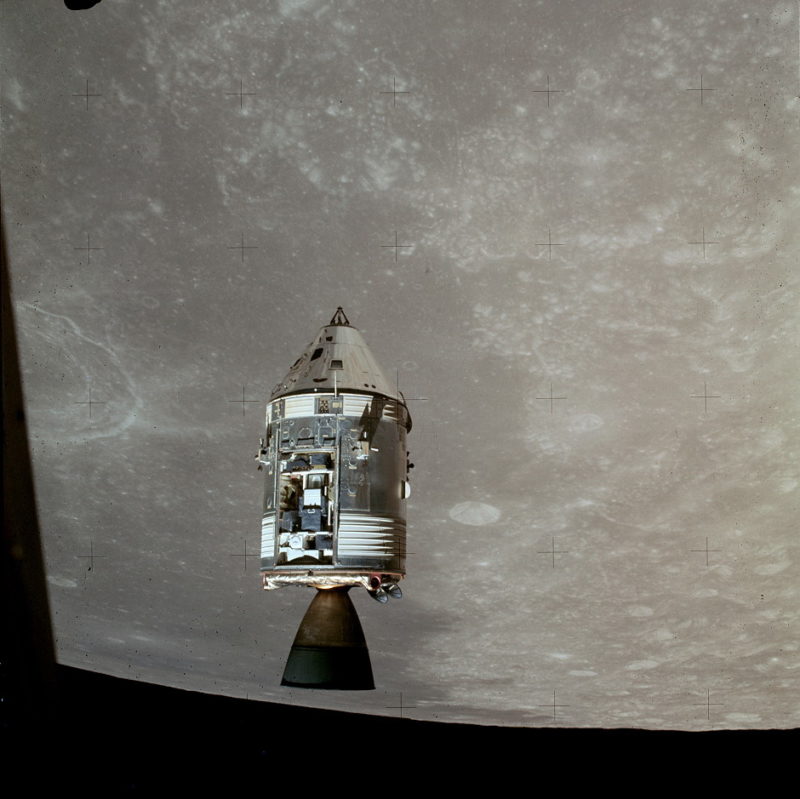

Humanity’s three most recent manned voyages to lunar distance, Apollos 15 through 17, took place between July 1971 and December 1972. Known as the “J-Series”, they were characterized by an upgraded Lunar Module (LM), capable of three-day stays on the surface, a spacecraft brimming with SIMBay instrumentation to comprehensively survey the Moon and a battery-powered Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) to expand the exploratory reach of each mission.

And on Apollo 15, as Commander Dave Scott and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Jim Irwin descended to the rugged terrain of Hadley-Apennine, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Al Worden—who died last year, aged 88—remained in orbit around the Moon, overseeing a significant program of observations and measurements.

Since the cylindrical SM could not survive re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere at the end of the mission, it was imperative that film cassettes from the SIMBay’s Panoramic Camera and Mapping Camera be recovered and brought inside Endeavour. These “deep space”, or “trans-Earth” EVAs, the first of which was performed by Worden on Apollo 15, took place further from the Home Planet than ever before.

In fact, the Moon still loomed large in the astronauts’ view, with the Home Planet hanging in the black sky like a blue-and-white football, some 197,000 miles (317,000 km) away. Following Worden’s spacewalk on 5 August 1971, Apollo 16 CMP Ken Mattingly and Apollo 17 CMP Ron Evans went on to perform their own trans-Earth EVAs in April and December 1972, respectively.

At first glance, risking humans to retrieve cassettes of camera film might appear unnecessarily foolhardy, but the reality of the matter was that spacewalking presented the least dangerous option.

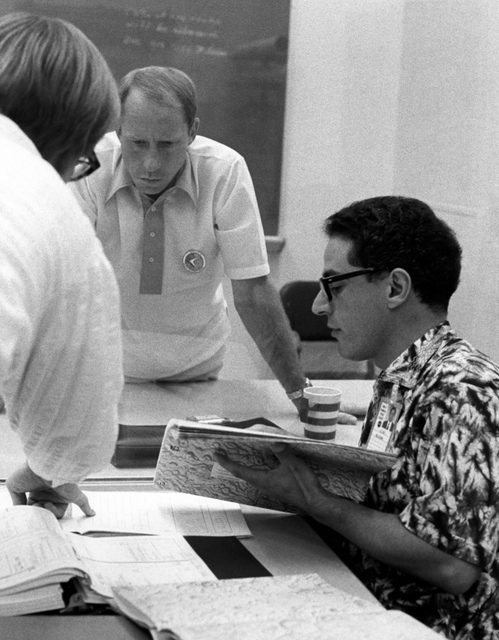

In a May 2000 oral history for NASA, Worden recalled that other methods had been discussed before the flight, including the use of a clothesline-like “reel” to tug the film cassettes out of the SIMBay and back to Endeavour’s hatch, but having an astronaut outside proved more practical.

“There had already been some preliminary work done on how to get this film out of the SIMBay,” Worden explained. “Of course, it had been in the pipeline for several years and there were a lot of schemes to get the film from…the back of the Scientific Instrument Module all the way up into the Command Module, a distance of about 30 feet. How do you get out there safely so that you don’t lose it, so that you don’t hurt something?”

Assigned to Apollo 15 in March 1970, by the time of the EVA on 5 August 1971 Worden had rehearsed every step of his task more than 300 times, both in the neutral buoyancy pool and aboard parabolic airplanes. After the mission, he would comment on the usefulness of training underwater for spacewalks, noting that it did not always mirror reality.

“The sensation of neutral buoyancy is sufficiently removed from zero-G that with too much training…it turns out to be negative training,” he said. In Worden’s mind, one or two sessions in the pool would have been “perfectly adequate”.

Two of the SM’s “quads” of maneuvering thrusters—namely Quads A and B, which sat directly adjacent to the SIMBay—were disabled to preclude any risk to the astronaut. And inside Endeavour’s cabin, guard-rails were installed over the instrument panel to ensure that no controls were accidentally nudged.

Since the cabin itself needed to be reduced to a state of vacuum for the EVA, both Scott and Irwin also were obliged to don their space suits, which they plugged into the spacecraft’s oxygen circuit. Worden wore Scott’s Lunar Extravehicular Visor Assembly (LEVA)—with its characteristic Mohican-like red stripe—over his own bubble-like helmet to afford him protection from the harsh ultraviolet sunlight.

He also attached a 24-foot-long (7.4-meter) tether to his suit before venturing outside. Irwin, meanwhile, donned a shorter tether to allow him to position himself in Endeavour’s open hatch. It would be Irwin’s job to help manage the snake-like twirling of Worden’s umbilical, as well as operate cameras and receive the film cassettes as they were brought back from the SIMBay.

Preparation for the EVA began the previous evening, 4 August 1971, only a day after Endeavour had barreled out of lunar orbit following one of the most spectacular missions of scientific exploration in human history. The astronauts spent a couple of “get-ahead” hours that night reconfiguring Endeavour’s cramped cabin, preparing EVA bags and rearranging stowage. Bagfuls of Moon rocks were tied to the walls to afford greater movement.

“Rearranging the stowage,” Worden said later, “was kind of the detail-part of some of the EVA prep that we did the night before.” Thanks to their attention to detail, by the time Scott, Worden and Irwin awoke on the morning of the 5th, the cabin was shipshape and ready for the EVA.

“The only problem was time,” remembered Scott. Although they had started “EVA Prep” a couple of hours earlier than planned, they wound up doing the final cabin pressure integrity checks right on the timeline. “That means that took us almost two hours longer than pre-flight planning,” he said later. “We were very happy that we had started early. We were glad that we had Al configure the cabin the night before to take care of the little details.”

From his own recollection, Worden felt that weightlessness actually made him work more methodically than in pre-flight training. “We never rushed at any time,” he reflected. “It flowed very smoothly, but a little slower than we anticipated.” But as far as Scott was concerned, having this “good time pad” all the way through the process meant that although the crew was not operating at maximum efficiency, relative to time, they were able to execute their preparations with comfort.

“The hatch is open!” radioed Worden with a contained measure of triumph as the spacewalk began. Irwin noticed that this simple act of opening the hatch created an effect not dissimilar to a vacuum cleaner, as unsecured objects drifted hither and thither, including toothbrushes and cameras.

Unlike previous EVAs—with Earth readily visible “above” or “below” one’s position—Worden found himself instead surrounded on all sides by the pitchest blackness and one of the few sources of available illumination was sunlight, reflected by the SM’s shiny surfaces.

Worden kicked off proceedings by setting up a television camera and the 16-millimeter Maurer Data Acquisition Camera (DAC) on a bracket at the hatch, to enable Mission Control to observe his every move.

Over the course of the next 39 minutes, he made three trips between Endeavour’s hatch and the SIMBay, retrieving the Panoramic Camera and Mapping Camera cassettes, then pausing to check on the condition of the other instruments. During this period, his sole complaint was that his tether proved a little short, particularly when he approached the “end” of the SM.

Working briskly, Worden removed the metallic cover from the Panoramic Camera, then the fabric cover, and finally released the film cassette. “It was no problem handling it,” he said after the mission. “I just very carefully drifted it back towards the hatch, keeping my hand on the handle and maneuvering myself back. It did release it at one time, because I had to use both hands to maneuver myself over the Mapping Camera. But I didn’t release it clear to the end of the tether. I just let go for a minute, repositioned myself and then grabbed it with the handle again.”

Throughout it all, Worden’s heart-rate peaked at about 130 beats per minute.

Worden passed the Panoramic Camera cassette to Irwin, who handed it off to Scott, who stuffed it down into Endeavour’s Lower Equipment Bay (LEB) for the homeward journey.

“Beautiful job, Al, baby,” chortled Capcom Karl Henize, seated at his console in Mission Control. “Remember, there is no hurry up there at all.”

“Roger, Karl,” said Worden. “I’m enjoying it.”

Sixteen minutes into the EVA, he returned to the SIMBay for the Mapping Camera cassette. And this time, he met greater difficulty. “That particular cover is set under a flange on either side,” Worden remembered later. “It’s held down by some pins at the release end of the cover. I had to twist it a little bit and pull it a lot harder than I had anticipated to release it from the flanges at the side. But it did come off all right; there was no problem.”

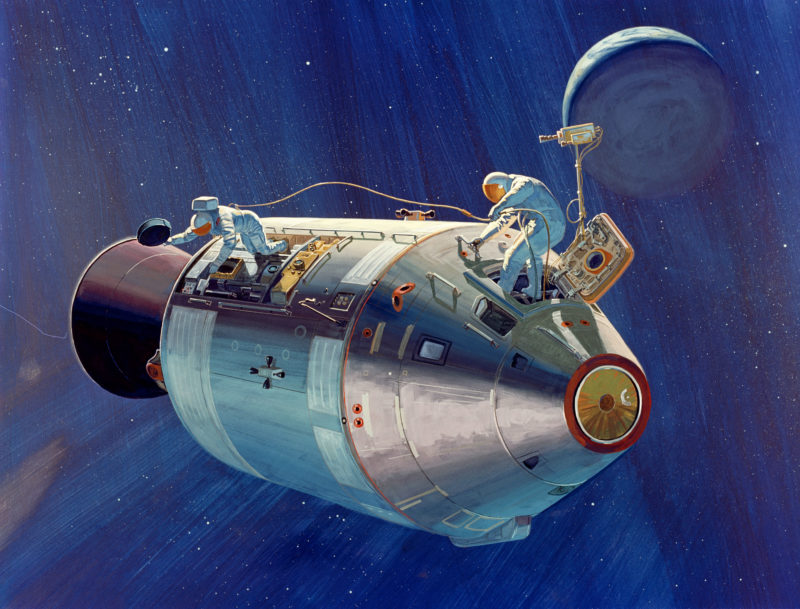

One of the lasting regrets of the first trans-Earth EVA was that, aside from a few blurred stills and the video, we have only the astronauts’ recollections of the true splendor of this first-ever spacewalk roughly equidistant between the Home Planet and its natural satellite. At one point, Worden caught sight of Irwin, perched in Endeavour’s hatch. And the spectacle was truly electrifying.

“Jim, you look absolutely fantastic against that Moon back there,” he breathed. “That is really a most unbelievable, remarkable thing.”

Without a camera to snap a picture, Worden could not capture the scene for posterity. But the artist Pierre Mion later painted it for National Geographic.

Finally, after 39 minutes and 7 seconds, Worden declared “Hatch is locked” and the first trans-Earth EVA was officially over. “It took hardly any force at all to close the hatch,” he said later. “It operated very smoothly and very freely. I pulled it right down to the point where it was closed. A couple of pumps on the handle and the latches were over and off. It was a very simple operation.”

Five decades on, Worden remains one of only three humans to have physically left his ship and maneuvered outside in cislunar space. After the event, he described the “unique perspective” he was granted. “I did have a chance to stand up on the outside [of the SM] and look. I could see the Moon and the Earth at the same time. And if you’re on Earth, you can’t do that, and if you’re on the Moon, you can’t do that. It’s a very unique place to be.”

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » Apollo »

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:A Very Unique Place: Remembering the First Deep-Space EVA, Five Decades On