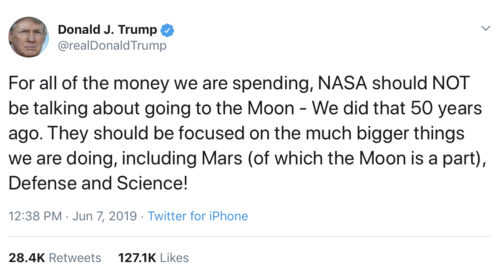

President Trump, in a tweet on June 7th at 1:38 PM, publicly put himself at odds with a policy directive that he himself signed just a year-and-a-half ago. That directive, Space Policy Directive 1[1], signed on December 11, 2017, changed space policy by amending the Presidential Policy Directive–4 of June 28, 2010[2]:

The paragraph beginning “Set far-reaching exploration milestones” is deleted and replaced with the following:

“Lead an innovative and sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international partners to enable human expansion across the solar system and to bring back to Earth new knowledge and opportunities. Beginning with missions beyond low-Earth orbit, the United States will lead the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization, followed by human missions to Mars and other destinations;”.

It appears that the President’s spontaneous outburst wasn’t conceived through careful consideration or advice from his own appointed leader of NASA, Jim Bridenstine or the National Space Council Executive Director Scott apace or it head, Vice-President Pence. As pointed-out by Matthew Gertz, the President’s outburst was at least somewhat motivated by an interview of NASA CFO Jeff DeWit by Neil Cavuto on June 7, 12:26 PM,

Neil Cavuto: ”[NASA is] refocusing on the moon, the next sort of quest, if you will, but didn’t we do this moon thing quite a few decades ago?”

One could ask whether, given all of the tweets the President tweets daily, does this one, single tweet even matter? From a legal standpoint, President Trump’s tweet changed no policy, programs of record, or budget requests. Yet, as the President of the United States, President Donald Trump’s words carry consequences whether deliberate or spontaneous. Sometimes, indeed perhaps even often, those words, delivered via Twitter, have not served him well nor furthered his goals. Whether this is one of those instances remains to be seen.

Although President Trump’s June 7th tweet didn’t “officially” change anything regarding U.S. space policy or current programs, what his tweet did do is leave people, most importantly, at least from a money perspective, those on Capitol Hill, with the feeling that the President’s support for an reinvigorated Moon program is shallow, if not at best tenuous.

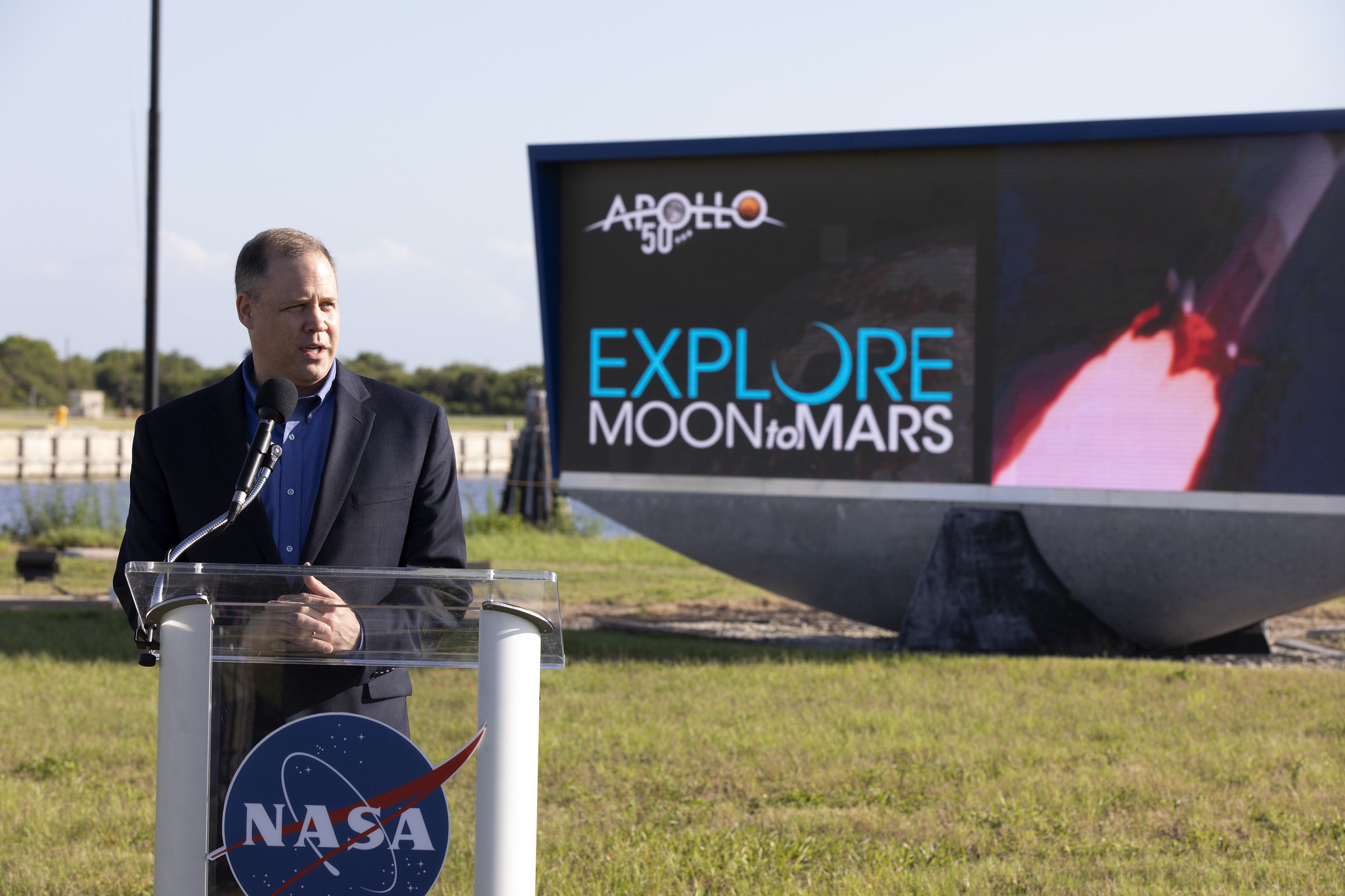

And given the tenuous state of the request by the White House for an additional $8 billion for NASA’s Artemis program, of which $1.6 billion has recently been requested for fiscal 2020 to speed-up the development of SLS and begin the development of landers, spacesuits, etc. for returning astronauts to the Moon’s surface by 2024, one would be hard-pressed to find a worse time for the President’s tweet. Where President Trump finds his Administration’s space efforts today is in a far less happy place than just weeks ago.

The Trump Administration’s space exploration goals, as stated in Space Policy Directive–1, to move beyond low-Earth orbit and return to the Moon is consistent with the policy goals and authorization law for space exploration since the NASA Authorization Act of 2005[3], the NASA Authorization Act of 2008[4], the NASA Authorization Act of 2010[5], and the NASA Transition Authorization Act of 2017[6].

Members of Congress with NASA oversight are well aware that President Trump’s effort to focus on returning to the Moon is only possible because Congress kept the Orion and Space Launch System programs authorized and funded in spite of what was, putting it most charitably, apathy by the Obama Administration.

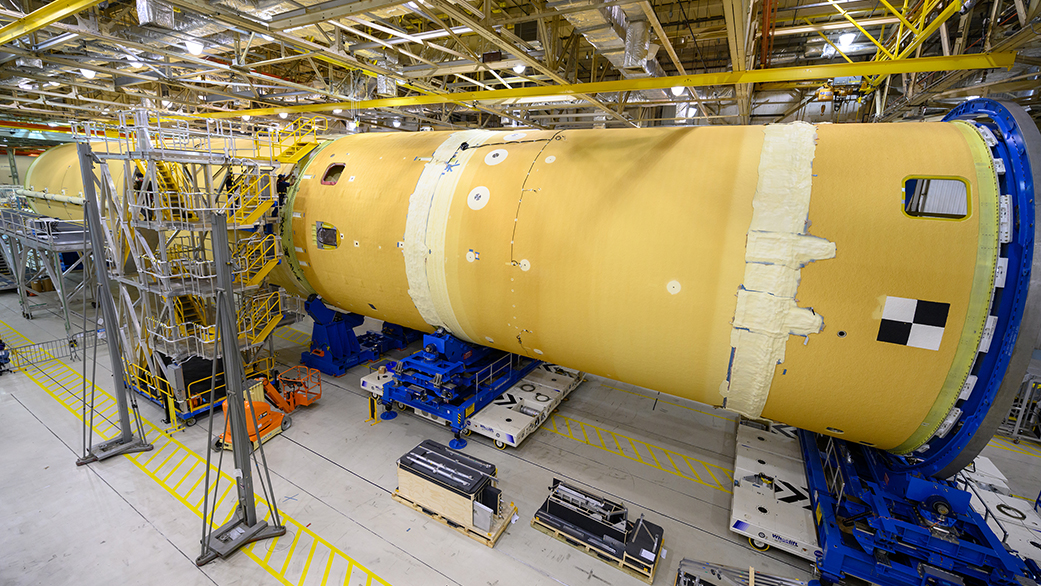

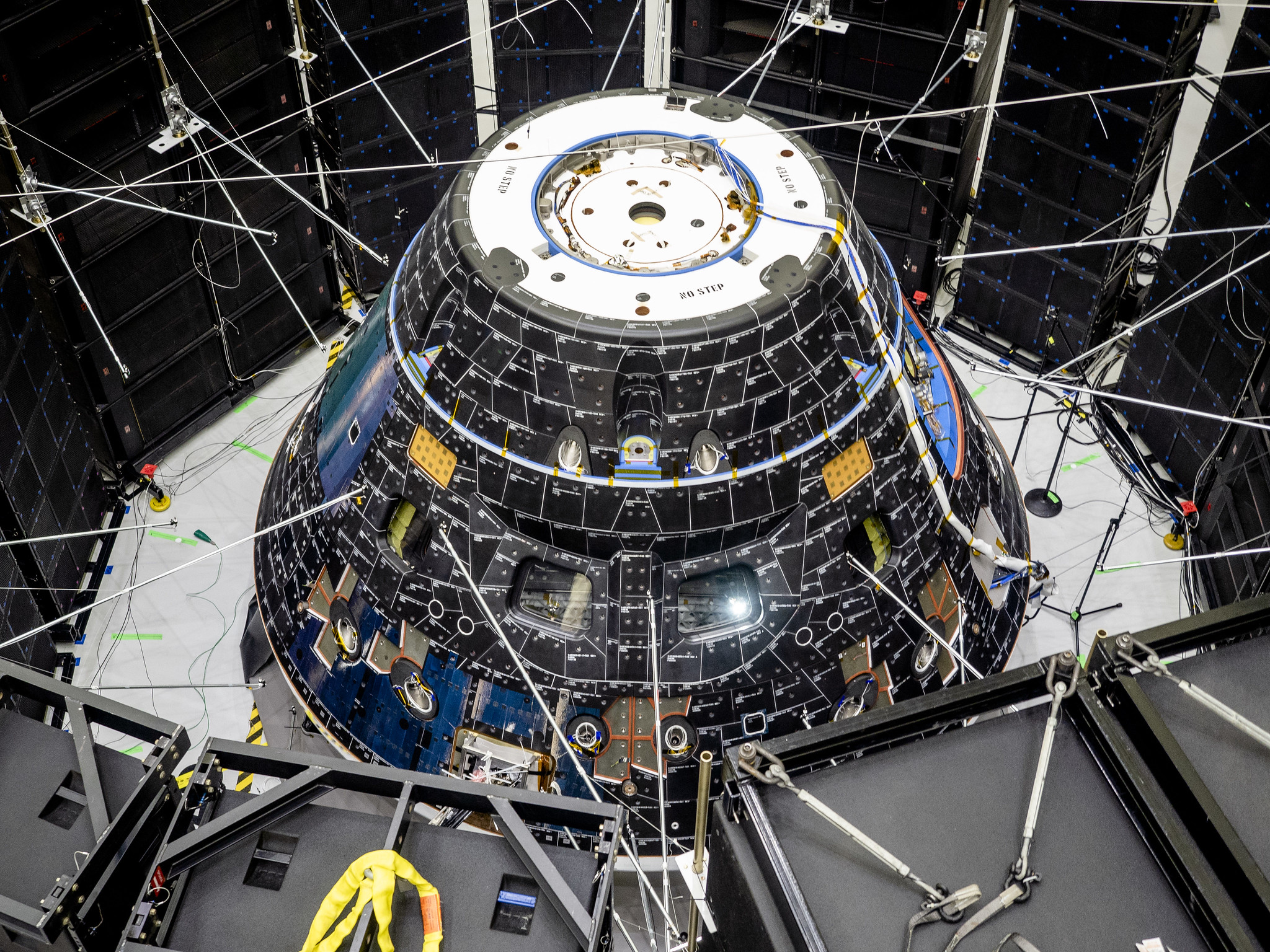

Unlike previous efforts to return to the Moon that would have required years of development and construction of elements, actual flight hardware is today already well along in the process of being built for a lunar orbit mission, until recently termed Exploration Mission–1 (EM–1). Continuity by Congress over the last nearly 9 years in maintaining authorization and funding support for the Orion and Space Launch System programs means, as stated in the NASA Authorization Act of 2010 that the “…United State government has its own transportation to access space”[7] in order to, as reaffirmed in the National Aeronautics And Space Administration Transition Authorization Act of 2017, promote its “…leadership in the exploration and utilization of space…”[8].

The White House’s initiative in the spring of 2019 to accelerate the return to the Moon by 2024 rather than 2028 was initially welcomed in space circles in the House and Senate. But within weeks after Vice-President Pence’s March 26th announcement that NASA was being directed by President Trump to undertake a crash program to land astronauts on the Moon within the next five years, there was criticism leveled at NASA about its human space exploration efforts. As even a cursory reading of NASA authorization law spanning 2005 through 2017 makes it obvious that such criticism isn’t directed at NASA because the space agency is getting ahead of where Congress wants it to go, namely returning to the Moon as part of a program to explore Mars. Instead, the criticism was that, if NASA is to move-up an effort to land astronauts on the Moon, to members of Congress NASA in particular, and the Trump Administration in general, did not appear to be moving expeditiously in making the difficult choices of how that goal would be accomplished, how much extra funding would be needed, and how it would pay for that additional funding.

In a May 8th hearing before the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee’s Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee, Rep. Kendra Horn (D-OK), Chair of the House Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics pressed Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA’s Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations, about when NASA would provide information on the cost, program changes, and the role the current NASA programs would play in accelerating a landing on the Moon[9]:

”While public-private partnerships have a role to play, their use in human spaceflight programs has not yet been demonstrated. Commercial crew providers were awarded contracts in 2014 with an initial plan for certification by 2017. It’s 2019 and while they’re making good progress, we’re still hitch-hiking with the Russians to low-Earth orbit. Not only that, under those contracts, it’s the companies, not NASA, that decide what information to make public should something go wrong. Spaceflight is risky, and things do go wrong.

Let me be clear. I support America’s robust, growing, and innovative space industry. A United States human space exploration program that leads the world should be leveraging private sector innovation. The question is how.

At present, we have a White House directive to land humans on the Moon in 5 years, but no plan or no budget details on how to do so, and no integrated Human Exploration Roadmap laying out how we can best achieve the horizon goal—Mars. In essence, we’re flying blind.”

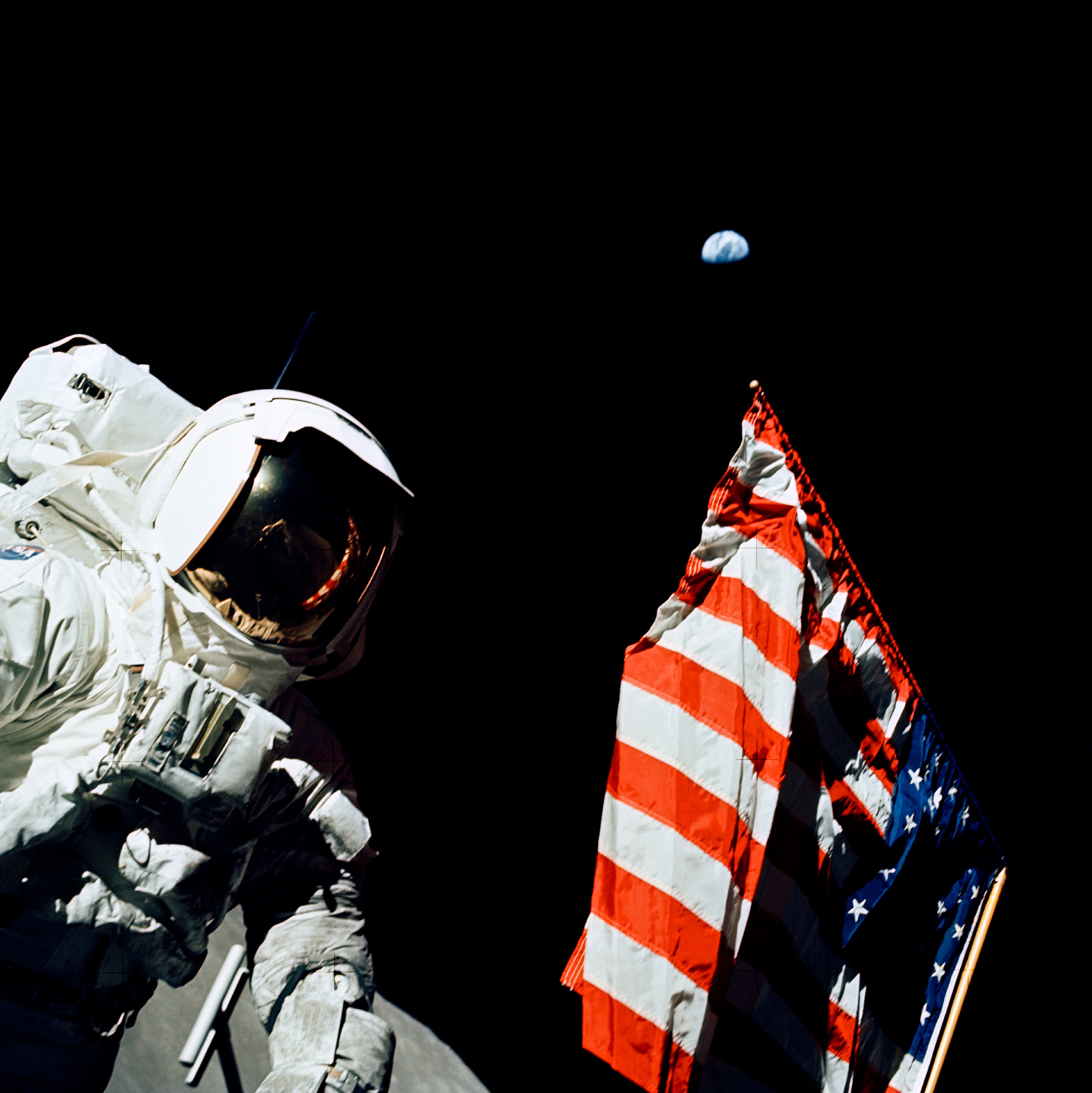

During her opening comments before the May 8th hearing, Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, Chair of the full House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, who has over the decades been a strong supporter of NASA human space exploration efforts, raised concerns that President Trump’s efforts to accelerate the current space program, one that only moves up the date that NASA would otherwise return to the Moon, might not experience smooth sailing[10], “…if Congress is to increase NASA’s budget simply to speed up a lunar landing relative to what was already planned, Congress will have to weigh the opportunity costs of doing so.” while also noting that, “I believe that human missions to the Moon and Mars, as well as robotic exploration, will continue to inspire as it did when Americans first walked on the Moon.”

Photo Credit: James Blair

The White House’s May 13 request for additional funding to accelerate a return to the Moon by 2024 was briefly welcomed in space circles in Congress. But only briefly. The welcome mat seemed to vanish when it was realized that the fiscal year 2020 $1.6 billion down payment on the total $8 billion was to be funded on the back of the Pell Grant, a widely popular financial subsidy program that has helped many a college student from going deeper into debt while pursuing a degree. A request for funds by a president that seeks money from a program much more popular in Congress than said unpopular President certainly gives new meaning to challenged. And House appropriators didn’t disappoint in their response.

Appropriators in both houses of Congress have for years been trying to re-establish “regular order”, which existed for appropriations prior to 2006. As part of this effort, as Marcia Smith recently reported, appropriators this year targeted completion of mark-up’s before Congress’ Memorial Day recess[11]. The work for markup for the House Appropriations Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Subcommittee had begun, as noted by Chairman Serrano, in January and was non-stop through May.

The House CJS Subcommittee’s markup for 2020 was over and done with May 16 sans funds for the White House’s request for $1.6B to accelerate Artemis for a 2024 landing. That means two things. If the $1.6B request for Artemis is to come in the current appropriations legislative cycle, then any hope for funding an accelerated lunar program now falls to the Senate. Specifically, those hopes rest on the very shoulders of one Senator Richard Shelby, the Chair of the full Senate Appropriations Committee. However, there has been nothing in the way of news on this front. Resolving the differences in NASA funding, specifically for accelerating Artemis, would then be left to reconciliation of the House and Senate appropriations bills. Otherwise, to get the $1.6B would mean a supplemental appropriation, a tall order.

The effort by NASA to organize an office that would oversee the Artemis Moon program, part of which would have come out of NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Directorate, currently led by Bill Gerstenmaier, ended ingloriously two weeks ago[12].

Add the President’s tweet of June 7 into the mix of these events, and what one has is the President “helping” the effort to get Congress to buy-into and fund the effort to accelerate landing on the Moon by 2024 as much as a 10 gauge shotgun “helps” scratch an itch on ones’s foot just as one was considering running a marathon.

Neil Cavuto and the President are only partially right; our parents and grandparents did go to the moon. But “we” did not; “we” have been stuck in low-earth orbit since Nixon ended the lunar program a generation and a half ago. Given the current difficulties in returning to the Moon, it is crystal clear that many of the lessons and rules of the road for successfully going to the Moon learned by our ancestors have been severely eroded by the waves of time. The unknown challenges of deep space inherent in a voyage to, and stay upon, Mars that would last years-long makes such a loss all the more biting.

None-the-less, some supporters of the President, who until June 7th supported an accelerated lunar program, will say that Trump is right, that we should ditch our congressional authorized and funded lunar program, defund the Lunar Gateway, and focus on Mars and a landing there in the 2030’s. Others will maintain their steadfast view that progress in space exploration is build upon successfully stepping from one challenge to the next, from the Moon to the asteroids; then to Mars’ moons Demos and Phobos; then upon Mars itself; to Jupiter’s moons; and beyond.

In the end, President Trump’s June 7th tweet might do some good. First, it may light a fire under those working on the Moon program. But more importantly, it may finally put an end to the space community’s wish for another Kennedyesque space initiative, one that seems, based on history, to last only a single Administration[13]. President Trump’s seeming tidal space focus instead affirms that that it is Congress, not the presidency, that provides a steady hand upon the tiller of space policy and keeps us moving inexorably farther outward.

- Space Policy Directive–1 ↩

- Presidential Policy Directive–4: National Space Policy ↩

- NASA Authorization Act of 2005, Title I, Sec. 101, (b) (PL 109–155; 42 USC 16611) ↩

- NASA Authorization Act of 2008, Title IV, Sec. 402 (1), Sec. 403 (PL 110–422; 42 USC 17731) ↩

- NASA Authorization Act of 2010, Title III, Sec 301 (PL 111–267; 42 USC 18321) ↩

- NASA Transition Authorization Act Of 2017, (PL 115–10; 131 STAT. 21 ↩

- “While commercial transportation systems have the promise to contribute valuable services, it is in the United States national interest to maintain a government operated space transportation system for crew and cargo delivery to space.”, NASA Authorization Act of 2010, Sec 2 (9) (PL 111–267; 124 STAT. 2808; 42 USC 18301 (9)) ↩

- “In order to ensure continuous United States participation and leadership in the exploration and utilization of space and as an essential instrument of national security, it is the policy of the United States to maintain an uninterrupted capability for human space flight and operations”, NASA Transition Authorization Act Of 2017 (PL 115–10; 131 STAT. 35; 51 USC 50101 ↩

- Opening statement by Rep. Kendra Horn, Chair of the Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics, for the May 8, 2019 Hearing, “Keeping Our Sights on Mars: A Review of NASA’s Deep Space Exploration Programs and Lunar Proposal” ↩

- Opening statement by Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, Chairwoman of the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology for the May 8, 2019 Hearing, “Keeping Our Sights on Mars: A Review of NASA’s Deep Space Exploration Programs and Lunar Proposal” ↩

- No Extra Moon Money in House Committee CJS Bill ↩

- Sirangelo to NASA — Hi and Bye ↩

- A Short History of Presidential Vacillation: Mars or The Moon ↩

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

Defending Trumps’ tweets is as pointless as defending the SLS. Both are very close to irrelevant to a serious space effort.

The horde of spacex fans that have spewed their garbage death-to-SLS filth for years are the worst thing that has ever happened to “space effort.” A propaganda war against the space agency SHLV is anti-space, anti-American, and those involved should take the pledge:

“I pledge allegiance to Musk and SpaceX, and the Ayn-Rand-in-space-libertarians which I am united with, one ideology, corrosive and ruinous, based on treason and placing the company above country and above all.”

Hah haha ha ha. We’d be a lot less skeptical of the sls if it wasn’t such a bloated piece of bureaucratic bs. The reason musk has inspired support is that he shoved aside the bureaucracy and actually started building a rocket. We can see progress. It hiccups, but it’s happening.