Thirty-five years ago today, on 17 June 1985, a spacecraft roared aloft with a crew representing the largest number of nations ever flown into space and carrying the largest load of satellites ever put into space at that time by a crewed vehicle. Aboard veteran shuttle Discovery for Mission 51G—the fourth of nine flights undertaken by NASA’s fleet of reusable orbiters that year—were U.S. astronauts Dan Brandenstein, John “J.O.” Creighton, Shannon Lucid, John Fabian and Steve Nagel, together with Frenchman Patrick Baudry and Saudi Arabia’s first man in space, Prince Sultan Abdul Aziz al-Saud.

Unsurprisingly, within the non-politically-correct corners of NASA’s astronaut office, 51G had drawn the disparaging nickname of “The Frog and Prince Flight”.

In the months and years preceding the Challenger disaster, NASA’s confidence in the shuttle fleet had led to agreements to fly U.S. politicians and foreign nationals as payload specialists. If a customer’s satellite or experiment filled more than a certain volume, an accompanying seat for a human passenger was offered. Mission 51G carried the French Echocardiograph Experiment (FEE) and an Arabsat communications satellite, so it came as little surprise when Baudry and al-Saud drew payload specialist spots on the flight. And as a member of the Saudi ruling family, al-Saud became the first person of royal blood ever to venture into space. “It was obvious to us all,” joked Creighton in a NASA oral history, “that Prince Sultan had grown up in different financial circles than the rest of the crew!”

But John Fabian did not like it. “This was an unhealthy environment,” he told a NASA oral historian, years later. “We were taking risks that we shouldn’t have been taking. We were shoving people onto the crews, late in the process, so they were never fully integrated into the operation of the shuttle and there was a mentality that we were simply filling another 747 with people and having it take off from Chicago to Los Angeles. This was not that kind of vehicle, but that’s the way it was being treated.”

Discovery’s crew was tasked to deploy three communications satellites—Telstar-3D, the French-built, Saudi-owned Arabsat-1B and Mexico’s Morelos-A—as well as releasing and later retrieving a small scientific platform called “Spartan” for two days of independent astronomical observations.

On the night before launch, the 51G crew spent some time with their spouses at the “beach house” on Cape Canaveral’s Neptune Beach waterfront, enjoying a barbecue dinner and private seclusion. Creighton recalled seeing Discovery, a mile or so away, brilliantly bathed in 800-million-candlepower of xenon floodlights. The astronauts and their families toasted the success of their mission with a bottle of wine, then parted.

“NASA has everything scripted right down to the minute,” Creighton said later, “and they wake you up about four hours and 45 minutes before launch and you…take a quick shower and get dressed and go in, still half-asleep, into breakfast, and a bunch of photographers run in and take your picture and they bring out a big fancy cake with your patch on it.” After suiting-up, the astronauts departed the Operations & Checkout Building into a blinding blaze of flashbulbs which made Creighton wonder if he would ever reach the Astrovan safely. Out at historic Pad 39A—the same launch site from which the first Moon voyagers had departed, almost two decades before—the crew was astonished by the ethereal silence, punctuated only by the creaking and groaning of gaseous propellants boiling off from the External Tank. To Creighton, ascending the elevator and boarding the vehicle was an eerie experience.

Only Brandenstein and Fabian had flown before; the others were “rookies”. As Nagel took his seat on the flight deck, behind Brandenstein and Creighton, Fabian offered him a few final words before liftoff. “Nagel,” he said, “you’re in for one hell of a ride!”

Ignition of Discovery’s three main engines got underway at T-6.6 seconds, silencing any vocal chatter between the astronauts. “The whole vehicle starts rumbling and shaking,” said Creighton, “and you can’t believe that these big bolts are still holding you to the ground. It feels like it’s trying to rip itself off the ground.” Nagel looked forward at the commander and pilot and they both seemed to be visibly “vibrating” in their seats as first the main engines and then, at T-0, the twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) ignited.

“I was just mentally behind,” Nagel told a NASA oral historian in later years. “I think I was left on the launch pad, with my mind trying to keep up. It just all happened so fast. There was such a rush of events and the sights and sounds…were almost overwhelming!”

As Discovery left the ground at 7:33 a.m. EDT, Creighton caught a fleeting glimpse of Pad 39A’s tower passing his window and vanishing from sight. But as the shuttle gained speed and reached the edge of space, he could not believe how quickly the sky changed from blue to deep indigo to pitch black.

SRB separation came with a bright flash in the cabin, totally engulfing Discovery’s forward cockpit windows in flame for a half-second, before the remainder of ascent continued with electric smoothness under the push of the main engines. At 7:41 a.m., only eight minutes after liftoff, three times the force of terrestrial gravity—akin to having a gorilla on one’s chest—suddenly was gone, to be replaced with the call “Main Engine Cutoff”, yelps of joy from the crew…and weightlessness.

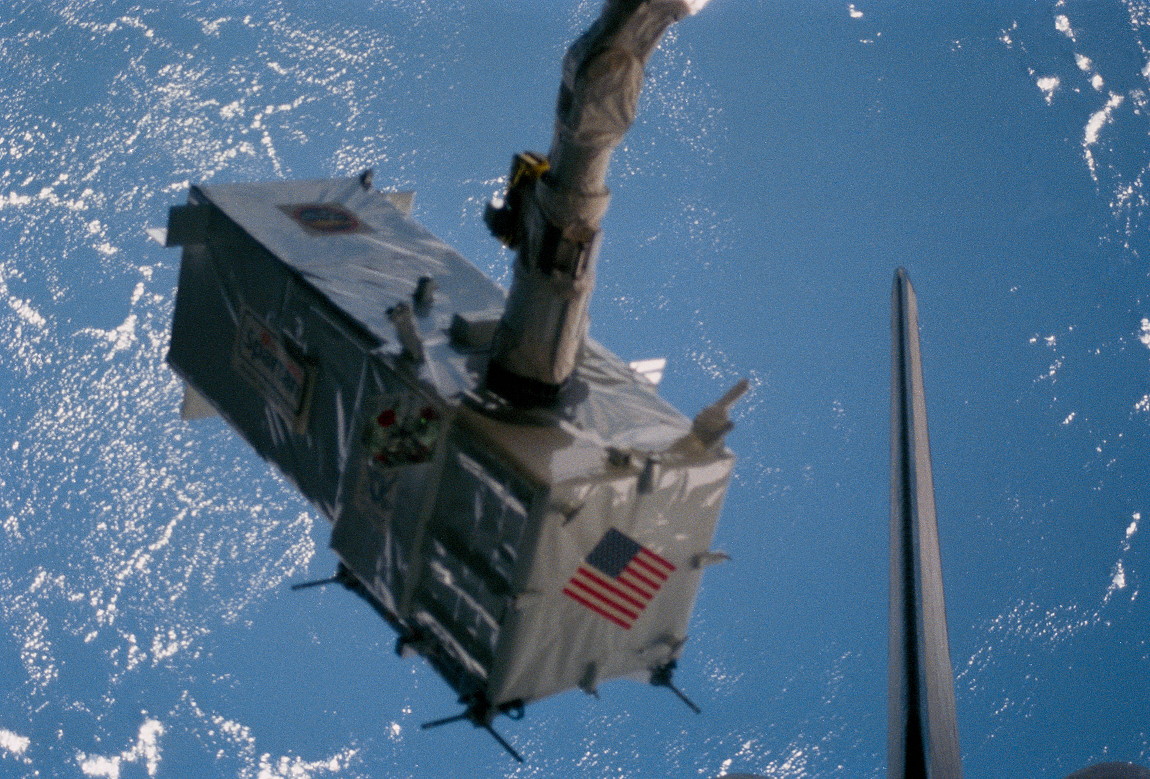

The next seven days would be busy days, with Arabsat, Morelos and Telstar to be deployed sequentially every 24 hours for the first half of the mission. Following their deployments, Lucid grappled Spartan with Discovery’s robotic arm and released the boxy satellite into space. Creighton pulsed the thrusters to move the shuttle to a safe distance about 100 miles (160 km) away and for two days Spartan performed medium-resolution mapping of X-ray emissions from extended sources and regions in the universe.

Its retrieval did not go entirely to plan, as Spartan was out-of-attitude and a couple of Discovery’s steering jets failed. It was, remembered Brandenstein, “a bit of an eye-opener” when they had to replan part of their rendezvous on the fly, but when Fabian finally snared the satelite he let out a whoop of joy which almost scared his crewmates to death.

A week in a volume no larger than a minivan was not pretty, even with the lack of “up-and-down” which came with weightlessness. Brandenstein and Creighton slept in their seats in the cockpit, with Fabian behind them. Downstairs on Discovery’s middeck, al-Saud tied his sleeping bag to the forward wall of lockers, Baudry and Nagel opted for a side wall and Lucid jammed herself into the tiny airlock.

Returning to Earth on 24 June 1985, and landing at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., Brandenstein was most impressed that he had secured the shortest distance—only 7,400 feet (2,250 meters)—from Main Gear Touchdown to wheelstop. For Baudry, a French Air Force fighter pilot, there was lighthearted disappoinment that Discovery was the first time he’d ever flown an airplane for the first time and he was not in control. “Well,” Brandenstein acquiesced with a grin, “we were able to walk away from it!”

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

I got to the Johnson Space Center in Jan 85 and by June was feeling like I knew my way around. The fun part of this mission (which I did not work on) was that the ArabSat people came around with big boxes of jackets, etc – all sorts of goodies that they gave away for free. I was an Air Force officer and some of the Air Force people that worked for me had to write letters to file that said that they had not given any special consideration in return for their gift, that was the case since the ArabSat people gave goodies to anyone in the room.

As a Payload guy, it did seem that the Payloads people had to come up with some token experiments in short order, to give the Prince something to do up there. It should be a concern that crews need to work together for a reasonable time, at that time NASA was throwing crews together with short times to train together.

The wonderful thing about this time was that the Saudi news was filled with stories about how their people were training with international crews, how they were doing experiments together, how we were working together. Now the news is filled with how we are in conflict! The news in Mexico and the hispanic world was filled with the same stories about how the world was working together, flying as a team.

That is one of the unrecognized (in some quarters) benefits of Shuttle – it brought us together and provided a counter to the areas where we have differences.

There was a significant microgravity materials science investigation on this mission. The Automated Directional Solidification Furnace (ADSF) flew in the mid deck to conduct the bismuth/manganese-bismuth eutectic growth experiments of Dr. David J. Larson, Jr. of Grumman Aerospace Corporation. These experiments were continued on STS-26, and complimentary experiments on samarium-cobalt were flown on STS-61C. For STS-51G, Shannon Lucid operated the ADSF and did a good job.

I haven’t seen Shannon in the grocery store for a while, next time I see her I’ll ask about that.

I was a young engineer on the PI’s (Dr. Larson’s) science team for those experiments. She did great.

The thing that I helped with (briefly) was a lucite plate with bubbles of water and oil, they were in various proportions. I think that the Prince shook this and photographed the oil and water separating. You might have heard of that.