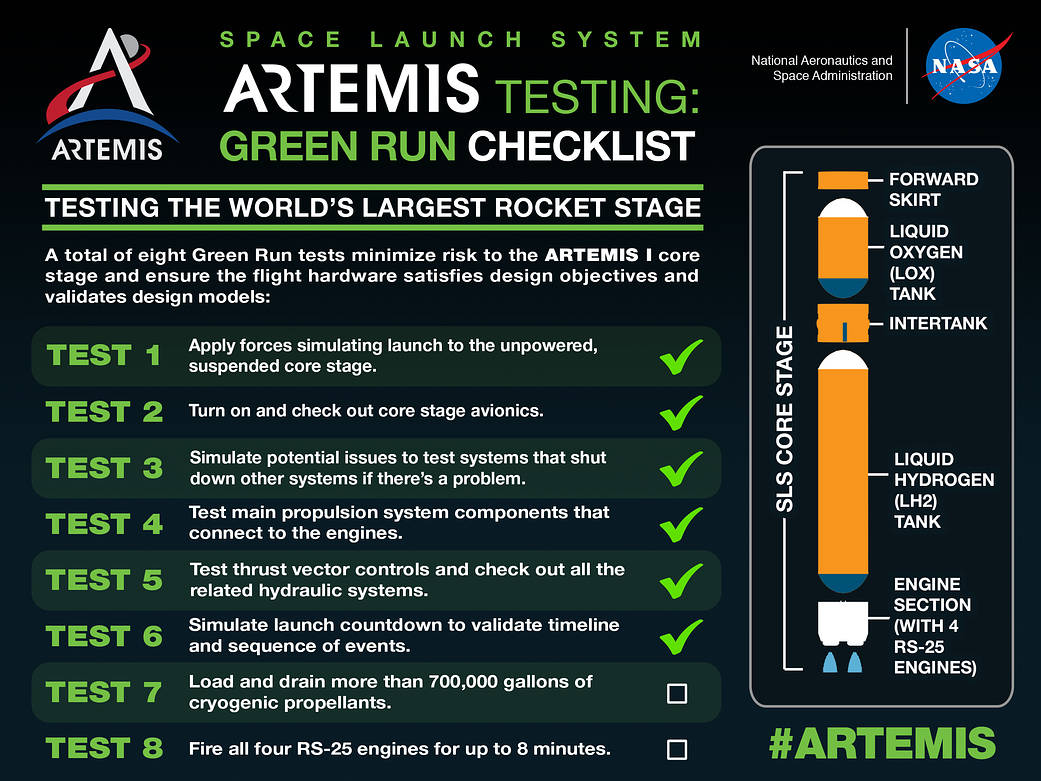

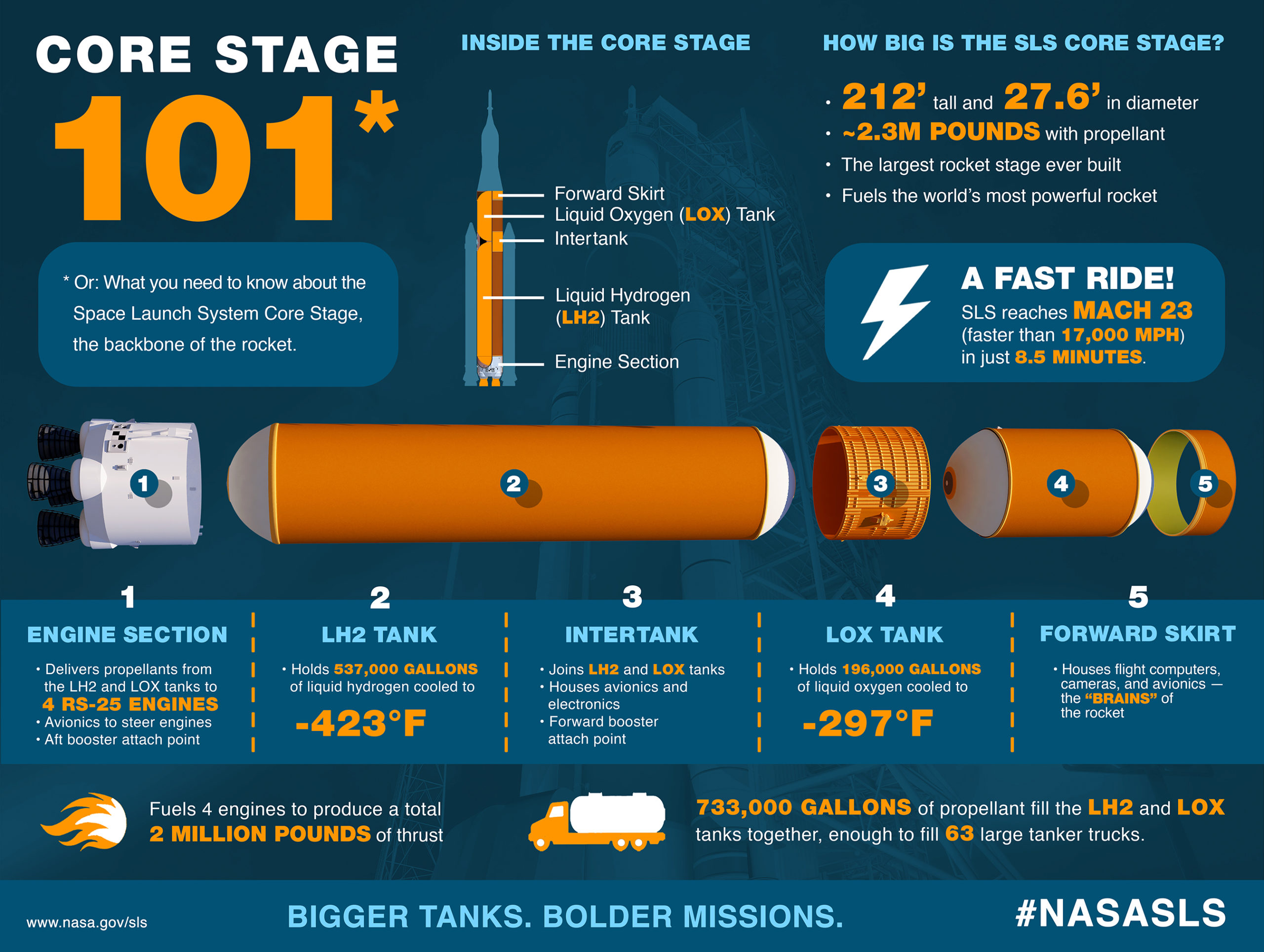

The core stage of the giant Space Launch System (SLS) rocket destined to ferry Artemis-1 around the Moon next year has moved one step closer to a Hot Fire Test of its four RS-25 engines. On Monday, NASA announced that engineers had completed the sixth of eight critical “Green Run” tests at the Stennis Space Center in Bay St. Louis, Miss., to evaluate the integrated functional and operational performance of the 212-foot-tall (64.6-meter) core stage.

Next up, the core will be loaded and subsequently drained with 733,000 gallons (3.3 million liters) of liquid oxygen and hydrogen propellants, ahead of the Hot Fire Test in early November. That crowning test of the Green Run will burn the shuttle-heritage RS-25 engines for a full SLS mission duration of around 8.5 minutes.

“More progress on @NASA_SLS Green Run Hot Fire,” tweeted NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, earlier this week. “NASA Stennis teams completed the sixth test of the Green Run test series—the simulated countdown—on Sunday, validating the stage for the sequence of events leading to an #Artemis launch.”

The core stage has resided in the B-2 Test Stand at Stennis since January 2020, where it is being put through a comprehensive series of tests to validate its functional and operational performance. Together with a pair of five-segment Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), the core provides SLS with 8.8 million pounds (3.9 million kg) of thrust to lift the Artemis-1 mission—the first voyage by a human-capable vehicle to lunar distance since Apollo 17 in December 1972—on its three-to-six-week voyage around the Moon in the second half of 2021. The booster segments were delivered by prime contractor Northrop Grumman Corp. to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida for processing back in June.

After arriving at Stennis from NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans, La., aboard the Pegasus barge in the second week of January, the core was hoisted into the cavernous expanse of the B-2 Test Stand. Within days, it completed its first test: the “Modal Test”, in which mechanized “shakers” imparted dynamic forces to identify bending modes as part of efforts to verify vehicle models to operate the Guidance, Navigation and Control (GNC) systems.

However, the worldwide march of the COVID-19 coronavirus pushed Stennis into a “Level Four” posture on the scale of NASA’s response framework in March, with only personnel for essential activities relating to the safety and security of the center permitted on site. “When Stennis closed in March, the team was initiating activities to start the Test 2, the avionics test,” SLS Stages Manager Julie Bassler told AmericaSpace.

“There were activities to secure and safe the hardware. When crews returned to work in late May, systems had to be reactivated and checked out for both the test stand and test control center. Teams were also working under constraints to ensure their safety and follow federal and CDC guidelines. With that in mind, once the test started, we maintained the same duration for the test as originally planned. There are periods for vehicle power-down, data analysis and re-activation between each test and to date, the tests are taking the amount of time that was planned.”

Work resumed in a reduced capacity in May and in late June the second Green Run test—the “Avionics Test”—was successfully completed. The avionics, including the flight control computers and electronics, as well as a multitude of sensors which gather flight data and monitor the health of the core stage in flight, were powered-up and checked out.

The third test, dubbed “Fail-Safes” and completed in early July, checked the rocket’s safety systems and simulated potential problems. The fourth (“Propulsion”) test, which wrapped up at the beginning of August, checked the core stage for leaks and evaluated command-and-control operations for the Main Propulsion System (MPS) elements which directly interface with the RS-25 engines.

However, the traumatic human consequences of COVID-19 was not the only direct impactor which hit the Green Run schedule. August brought a pair of exceptionally powerful natural forces in the menacing forms of Hurricanes Marco and Laura, which devastated the Caribbean Sea and threatened the Gulf Coast in mid-to-late August. This prompted NASA to pause Green Run testing on 24 August and secure both the core stage and B-2 Test Stand until the storms passed.

This was a pity, because the fifth Green Run test had originally been targeted to begin at around that same time. “We had started the facility preparation work for the Green Run Test 5,” NASA’s Tracy McMahan recently told AmericaSpace. “Due to the prediction of two hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico with potential impacts to Stennis Space Center, NASA made the prudent decision to put the valuable Artemis-1 core stage flight hardware and B-2 test stand in a safe configuration.”

After the dissipation of Marco and Laura, the Stennis teams resumed Green Run testing on 31 August and Test 5—the final “functional” test, dedicated to evaluating the core stage’s Thrust Vector Control (TVC) and hydraulics—was wrapped up early in September. With the end of these five functional tests, three “operational” tests could commence. These consist of Test 6 and the countdown simulation, followed by a fully-fueled Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR) as Test 7 and the Hot Fire Test itself as Test 8. However, even the start of Test 6 was delayed a few days, in response to the threat of Hurricane Sally.

In its update, NASA provided additional detail about the nature of Test 6, the steps involved and a tantalizing insight into what we can expect for the real thing, next year. “During the simulated countdown, NASA engineers and technicians, along with prime contractors Boeing and Aerojet Rocketdyne, monitored the stage to validate the timeline and sequence of events leading up to the test, which is similar to the countdown for the Artemis-1 launch,” it was explained.

“The countdown sequence for an actual Artemis launch begins roughly two days prior to liftoff. In addition to all the procedures leading up to the ignition of the four RS-25 engines, the SLS core stage requires about six hours to fully load fuel into the two liquid propellant tanks. The simulated countdown sequence test at Stennis began at the 48-hour mark, as if the stage was first powered up before liftoff. Engineers then skipped ahead in the sequence to monitor the stage and procedures of the stage ten minutes before the Hot Fire.”

“The simulated countdown test performs a step-by-step execution of the simulated tanking procedural operations and event timelines for final test-team training prior to Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR),” said John Cipoletti, SLS Green Run deputy test director for Boeing. “The training sessions included simulated fault scenarios to fully exercise the team’s communication and protocols. They served as a final verification of our readiness for WDR and the successful integration of the latest Green Run software.”

But even with three-quarters of the Green Run campaign now done, the hardest part is still to come. And Ms. McMahan has previously cautioned that NASA is not working to any definitive target dates. “For each of these tests, it is the first time they are conducting the test on a brand-new stage,” she told us. “So they don’t really have a hard-stop date. It all depends on what they find during the test, if they have to fix anything or make any adjustments.”

With the countdown simulation finished, NASA will conduct a Test Readiness Review in the coming days. “The time between each test depends on what we find in the prior test,” Ms. McMahan added. “The WDR is a big deal. It will be the first time the tanks have been filled with cryogenic propellants. The WDR will exercise every part of the stage that needs to work for the hot-fire, except actually firing the engines.”

During the WDR, the core stage tanks will be filled and later drained with 733,000 gallons (3.3 million liters) of liquid oxygen and hydrogen, the former cooled to -182 degrees Celsius (-297 degrees Fahrenheit), the latter to -252 degrees Celsius (-423 degrees Fahrenheit). There are two reasons for this fill-and-drain protocol.

“It will allow the whole system to be checked out and allow the tanks [and] propellant lines to be inspected afterwards and provide time for data analysis of all those systems,” Ms. McMahan explained, “and it will allow the team to simulate a scrub on the launch pad, should that happen in the future on a mission.”

Assuming that the Hot Fire Test occurs as planned in early November, NASA currently plans to refurbish the core stage and ship it to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in early January. Key areas for refurbishment, unsurprisingly, are the engines themselves. “The engine team will inspect the engine and determine what needs o be done after the test,” she told us. “Another area where they expect some refurbishment is in the foal thermal protection system.” Most of this work will be conducted at Stennis, prior to shipment.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » SLS » Artemis »