The opening weeks of every year are a somber time for America’s space program, as many minds reflect upon the triple tragedies of Apollo 1 and shuttles Challenger and Columbia and the catastrophic loss of 17 brave lives. And as Houston-based AxiomSpace prepares to launch the first all-commercial human space voyage later this fall (with a crew that includes movie star Tom Cruise), we look back this month at a real “Mission: Impossible” which took place 35 years ago, in January 1986.

Overshadowed by the tragic loss of Challenger on the 28th of that month, STS-61C was successful and Columbia’s astronauts returned home alive. But in the final days before their launch, disaster—euphemistically described as “a bad day” by STS-61C pilot and future NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden—almost engulfed another crew, not once, but twice.

The crew had been assigned more than a year earlier, in October 1984, and for a while it seemed that simply getting themselves a solid payload to fly would be an impossibility in itself. Commander Robert “Hoot” Gibson, pilot Bolden and mission specialists George “Pinky” Nelson, Steve Hawley and Franklin Chang-Diaz were initially pointed at a flight to deploy a pair of communications satellites and support autonomous experiments in the shuttle’s payload bay.

Then their mission changed to deploy a large NASA Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) and a Spartan free-flying payload to observe Halley’s Comet, before a raft of additional changes throughout 1985. By the end of the year, finally, they had been assigned a powerful Radio Corporation of America (RCA) communications satellite called Satcom Ku-1.

Gibson’s crew was also expanded to seven members with two non-professional astronauts as payload specialists. One of them, RCA’s Bob Cenker, would oversee the deployment of Satcom Ku-1. The other was originally meant to be a Hughes Aircraft engineer named Greg Jarvis, who had already been moved off several earlier shuttle missions and would be moved off STS-61C…onto a seat on Challenger’s tragic final voyage. In place of Jarvis was Congressman Bill Nelson, one of a series of politicians NASA was flying on the shuttle to curry favor with its political masters.

The first sense that 61C might turn into an impossible mission came during training when Gibson taught Bolden about shuttle systems and aerodynamics and the mysterious concept of “Hoot’s Law”. By his own admission, Bolden struggled during his first few months of mission-specific training; on one occasion, in the simulator, the instructors threw an engine malfunction at the crew.

Bolden accidentally shut down the wrong power bus, disabling a healthy main engine. “We went from having one engine down in the orbiter, which we could’ve gotten out of, to having two engines down,” Bolden told the NASA oral historian years later, “and we were in the water, dead.” If this simulation had been for real, the shuttle would indeed have been lost, with all hands.

Gibson turned to Bolden and patted his pilot on the shoulder. “Charlie, let me tell you about Hoot’s Law.”

“What’s Hoot’s Law?”

“No matter how bad things get, you can always make them worse!”

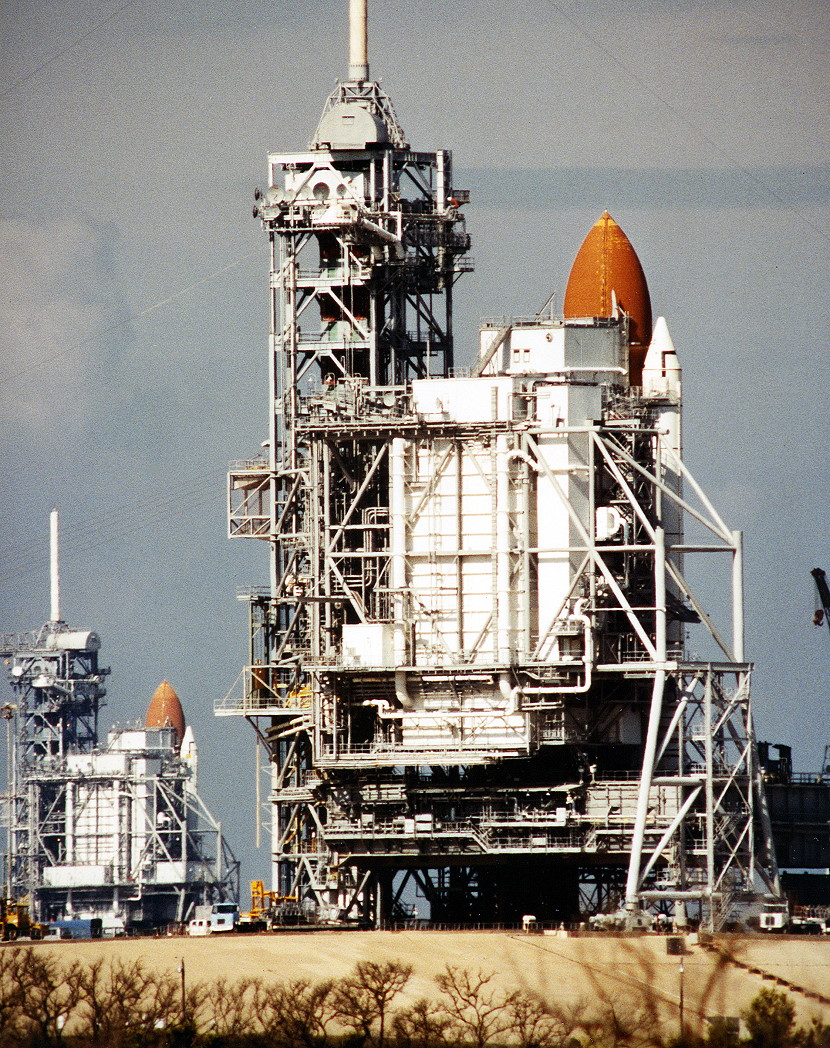

Gibson’s words proved ominously prescient. Scheduled to launch at 7 a.m. EST on 18 December 1985 as the tenth and last shuttle mission of that year, STS-61C was routinely postponed by 24 hours to give technicians more time to finish closing out shuttle Columbia’s aft compartment. Next day, the countdown was halted dramatically at T-14 seconds, when flight controllers received an indication that the Hydraulic Power Unit (HPU) on the right-hand Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) had exceeded its maximum allowable turbine speed limit.

“We were happy as clams,” Bolden recalled of the build-up to the second launch attempt. “All of a sudden, everything stopped and the countdown clock went back to T-9 [minutes] and kind of ticked there. We had no idea what had happened. As they started looking at the data, they had an indication that we had a problem with the right-hand booster.” Although the HPU fault turned out to be an erroneous signal, the launch window for the day had closed and the attempt was scrubbed.

With the impending Christmas holidays, STS-61C’s next launch date was set for 6 January 1986, which pushed it right up against the next mission, Challenger’s STS-51L, scheduled to fly later that same month. The delay also posited a problem for Columbia herself in terms of how quickly she could be turned around between flights, since she was set for another mission, STS-61E, in March 1986, to observe Halley’s Comet.

For the crew, the festive period was a chance to relax after more than a year of intensive training in the simulators and uncertainty over when they would ever fly. “We stayed in quarantine a lot of the time,” remembered Hawley in his NASA oral history. “When you’re in a launch mode, down in Florida, the pace is not very hectic. You’re not in training, like you would be if you’re in Houston and going to the simulators every day. You’re reviewing procedures and checklists and having a nice time, because you have the opportunity to sort of sit back without the pressure of having to be in a sim. I’ve always enjoyed the time in quarantine, although, because of the launch time, we were getting up at two in the morning every day!”

Columbia’s launch attempt on 6 January turned out to be one of the most hazardous yet in the shuttle’s operational history. The count was halted at T-31 seconds, following the accidental draining of 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) of liquid oxygen from the External Tank. The fill and drain valve had not properly closed when commanded to do so.

Launch controllers reset the clock to T-20 minutes and efforts were made to reinitiate the liquid oxygen tanking, but it was quickly realized that time was running out and the window would close before the vehicle was ready. Another 24-hour delay was called. The next attempt, on the 7th, was scrubbed due to poor weather at two Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) sites in Spain and Senegal.

Yet another try on the 9th similarly came to nothing when a liquid oxygen sensor on Pad 39A broke off and lodged itself in the prevalve of one of Columbia’s cluster of Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs). “That would have been a bad day,” Bolden recalled, grimly. “It would have been catastrophic, because the engine would have exploded, had we launched.” Heavy rain put paid to the next opportunity on 10 January, but the decision to scrub was met with a measure of relief by the crew.

“We went down to T-31 seconds,” said Bolden, “and they went into a hold for weather and it was the worst thunderstorm I’d ever been in. We were really not happy about being there, because you could hear the lightning! You could hear stuff crackling in your headset. You’re sitting out there on the top of two million pounds of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen and two [SRBs]. None of us were enamored with being out there.”

The repeated delays took a financial toll, too. Previously, astronauts were responsible for getting their families to Florida, paying their way, finding motel rooms for them, and putting them up. Pinky Nelson’s wife, Susie, spent three weeks in a condo at Cape Canaveral, waiting, and their young children ended up missing the launch because they had missed so much school and went back to Houston. “Had the accident occurred on that flight, instead of the flight afterwards,” said Nelson, “it would have been just a nightmare scene, because the families were scattered all over the place.”

Despite their frustration at the repeatedly scrubbed launch attempts, the astronauts tried to remain upbeat. “We tried to wear a different shirt each day,” joked Gibson at the post-mission press conference, “so that we’d know exactly just which attempt this was,” adding that the astronauts got very good to walking out to—and back from—the crew van. As for the cause of the delays, there could be only one person to blame: Steve Hawley.

When the astronauts left their quarters in the pre-dawn darkness of 12 January, Hawley had ridden the bus to the launch pad on ten occasions for only two liftoffs. To this day, he is confident that a conversation and agreement he had with Gibson may have helped to finally get Columbia into orbit. “I decided that if [Columbia] didn’t know it was me, then maybe we’d launch,” he said, “and so I taped my name tag with grey tape and had the glasses-nose-moustache disguise and wore that.” It worked, and 61C roared aloft at 6:55 a.m. EST.

It would be the last successful shuttle launch for almost three years.

I’ve always been fascinated by the back story to STS 61C. Some have said if Congressman Nelson wasn’t on the crew thhe mission would have been cancelled altogether to ensure STS 61E.

It’s also been suggested the Challenger disaster may never have happened — at least not on STS 51L — due to schedule pressures imposed by Nelson’s presence. Who can say for sure…

Hi Hari,

Hawley was quite vocal over the years in his belief that the 61C payload was not very robust (he even referred to 61C as a “clearance sale”) and he was convinced that Nelson’s presence was a deciding factor in allowing the mission to go ahead. Whether or not Columbia could have been prepared to launch 61E on 6 March can never be known. If it had been achieved, it would have beaten the 51J-61B launch-to-launch record by just 24hrs.