A quarter-century ago, today, Space Shuttle Discovery launched to Russia’s Mir space station for the final time, closing out a group of impressive rendezvous and docking missions which cemented a new partnership between two old rivals and laid the groundwork for the construction and early operation of the International Space Station (ISS). And a few days into the STS-91 mission, Mir Commander Talgat Musabayev pulled out a surprise gift for Discovery Commander Charlie Precourt: a 24-inch (60-centimeter) wrench.

“Charlie, take this wrench,” Musabayev grinned. “It’s sort of a relay stick from the Old Lady, Mir, to the International Space Station.”

“We’re going to need this,” Precourt replied, “for all the work we have ahead of us.”

STS-91, the ninth and final shuttle-Mir docking mission, was the end of a truly remarkable era which had seen NASA’s reusable fleet of orbiters transition from their post-Challenger role of launching and retrieving satellites and performing scientific research into a vehicle which could visit and build space stations. In December 1993, up to ten shuttle-Mir flights were agreed between the United States and Russia, leading to a cosmonaut voyaging aboard the shuttle in February 1994 and an astronaut spending four months on the station from March through July 1995.

This was followed by three years of shuttle-Mir docking flights, which delivered equipment and supplies and exchanged long-duration crew members. STS-91, commanded by Charlie Precourt, would lift 1,100 pounds (500 kg) of water and 4,630 pounds (2,100 kg) of cargo, experiments and necessities to the aging orbital outpost, as well as bringing home U.S. astronaut Andy Thomas after almost five months in space.

The crew was an unusual one. Named in two parts between October 1997 and January 1998, its core consisted of Precourt—the only American to fly three times to Mir—together with Pilot Dominic Gorie and Mission Specialists Franklin Chang-Diaz, Wendy Lawrence and future Glenn Research Center (GRC) Director Janet Kavandi.

For her part, Lawrence was originally pointed at a long-duration flight to Mir, but those hopes were ultimately thwarted: firstly, by being too short to safely fit inside Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft, earning her the unenviable nickname of “Too Short”, and secondly, by being unable to fit the Orlan (“Eagle”) Extravehicular Activity (EVA) suit. At length, she was reassigned to STS-86, the seventh shuttle-Mir docking in September 1997.

By the time she finally flew, Lawrence had already been notified by Chief Astronaut Bob Cabana that she would also fly STS-91, a few months later. “He felt pretty adamant about making sure that my participation in the program would be rewarded,” Lawrence told the NASA Oral History Project, some years later.

“What most people didn’t know at the time—what I knew—was that I would fly on 86 and I would fly on 91, so that’s why a lot of reporters just couldn’t understand why I wasn’t devastated,” Lawrence joked. “I knew that I was getting two flights out of it!”

So it was that within five hours of landing on STS-86 on 6 October 1997, Lawrence got a telephone call from Precourt, inviting her to their first STS-91 crew meeting. Two weeks later, the crew roster was announced.

And in January of 1998, veteran cosmonaut Valeri Ryumin—then serving in the capacity of program manager on the Russian side of the shuttle-Mir program—was announced as STS-91’s sixth crew member. Aged 58, he would become the oldest Russian to fly into space, a record that would remain unbroken until 59-year-old Pavel Vinogradov headed to the ISS alongside Aleksandr Misurkin and Chris Cassidy in March 2013.

Although Ryumin had flown three times previously, and was the first man to log almost cumulative year in space, his most recent mission had been in 1980, nearly two decades earlier. And that required him to lose 55 pounds (25 kilograms) in weight, pass various medical boards and obtain direct approval from his bosses to fly again. Ryumin would serve as an observer on STS-91, assessing the state of Mir, which had endured a major fire and partial depressurization the previous year.

STS-91 would also offer a nod to the forthcoming ISS era by flying with the first Super-Lightweight Tank (SLWT), an upgrade on the shuttle’s External Tank (ET), whose weight had been trimmed by about 7,500 pounds (3,400 kilograms). At 6:06 p.m. EDT on 2 June 1998, Discovery sprang from Earth on the 24th mission of her career, delivering the six-strong crew smoothly into orbit.

For Kavandi, ignition of the twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) brought tears to her eyes. “I was actually crying on the way up,” she recalled, “not because I was scared, but because it was just a flood of emotion as I felt all the power and everything thrusting us into space.”

Two days later, Precourt and Gorie guided their ship to dock with Mir. And over the next five days, they worked with the incumbent station crew of Russian cosmonauts Musabayev and Nikolai Budarin and NASA’s Andy Thomas.

Supplies were moved from a Spacehab pressurized cargo module in the shuttle’s payload bay. And work was also done with a test version of the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), which today sits at the ISS as a major particle physics instrument.

To his surprise, Precourt found Mir in better condition than on his most recent flight a year earlier. Although one of its modules was sealed off, following a collision with a Progress supply ship, he noticed the air was cleaner and the temperature was better.

“The walls of the surfaces of the structures everywhere were dry,” he said. “There had been lots of humidity on my previous two visits that was evident everywhere.”

But for Ryumin, it offered a quite different perspective. He was shocked by the amount of clutter aboard Mir—which he felt made acclimatizing to life in space more difficult for the station’s crews—and on one occasion he even found rubbish behind a wall panel.

Upon asking Russian flight controllers for permission to remove it, his request was turned down because the area housed critical electrical cables that could not be moved. Even Musabayev frequently deferred to Ryumin in space-to-ground conferences. On one occasion, where camera brackets did not fit properly, an irritated Ryumin told the ground that this problem needed to be noted in the mission report in red capital letters.

In these final days of the shuttle-Mir program, there was time for celebration. On 5 June, Ryumin passed a cumulative year in space, counting his three previous missions. The astronauts and cosmonauts observed the milestone with a joint meal and Musabayev pulled out his guitar and strummed a few Beatles numbers, a handful of traditional Russian and Kazakh folk-songs and tunes by Soviet singer-songwriter Vladimir Vysotsky.

On 8 June, Thomas transferred to the shuttle and Discovery undocked shortly after midday EDT. With Gorie flying the spacecraft, Precourt offered a few remarks to Canadian astronaut Marc Garneau, sitting in the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas.

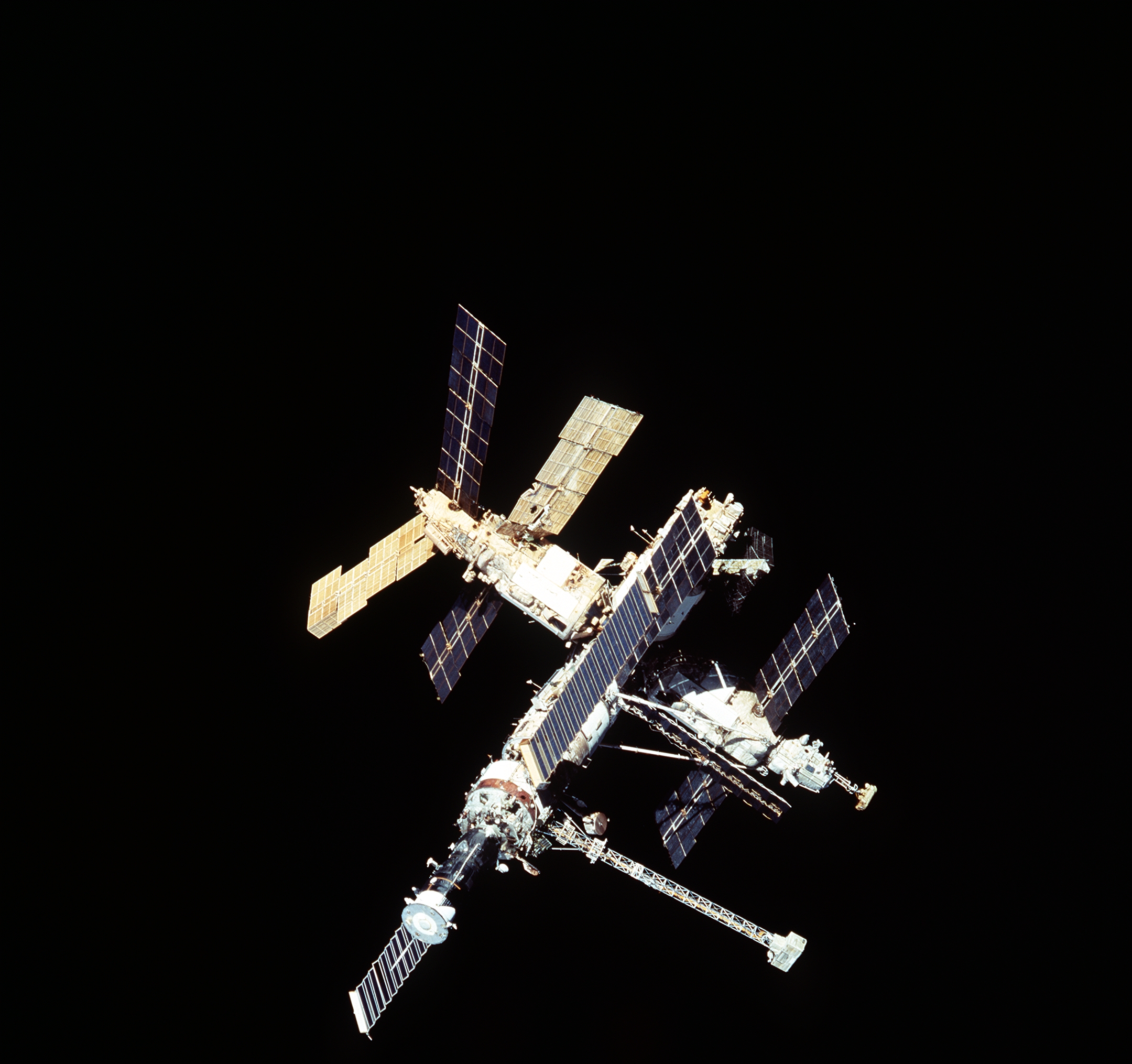

“It sure is a pretty view of the station, from here, with the Sun coming,” Precourt said. “We’re just sitting here in position and they’re tracking the Sun and it’s just glowing. It’s really something!”

“Enjoy the view,” replied Garneau, “because you’re probably the last crew to have a good look at Mir.”

There had been some hope, at least on the Russian side, that a tenth shuttle-Mir mission might fly. “To tell you the truth, I feel very sorry that…we will end our program,” Ryumin said in early 1998. “I don’t want to leave it at the ninth, so maybe we need to think about how we can extend this phase to include another, tenth, flight.”

Such hopes were inspired by Russia’s unwillingness to dispose of Mir, which would become a virtual inevitability without the lifeline provided by the shuttle and which Russians saw as a shining beacon of national pride. However, NASA Administrator Dan Goldin had been adamant that the program would end with STS-91 and emphasis would shift to the construction of the ISS.

Discovery’s landing thus brought down the curtain on a remarkable era and signaled the beginning of the end for Mir. The old station, whose first components had risen to orbit in February 1986—at the height of the Cold War—endured for another three years, seeing a handful of long-duration crews, the last of whom departed in June 2000.

Efforts to “commercialize” Mir and prolong its life ultimately came to nought and the station was deorbited in March 2001. Yet many astronauts, cosmonauts, engineers and managers agreed that the challenges of shuttle-Mir strengthened the two nations’ resolve and partnership to make the ISS work.

In the words of Wendy Lawrence, the Russians were no longer enemies, nor even simply comrades. In fact, they had become friends.

I worked the entire Mir program from Early Progress through to the end. It was exciting but the Mir was such a compromised vehicle that it was NEVER safe to fly in. I worked closely with Shannon Lucid, Dave Wolf, Mike Foale, etc and the Russian attitude towards safety was not acceptable. NASA didn’t take safety seriously but the Russians thought it was not needed.