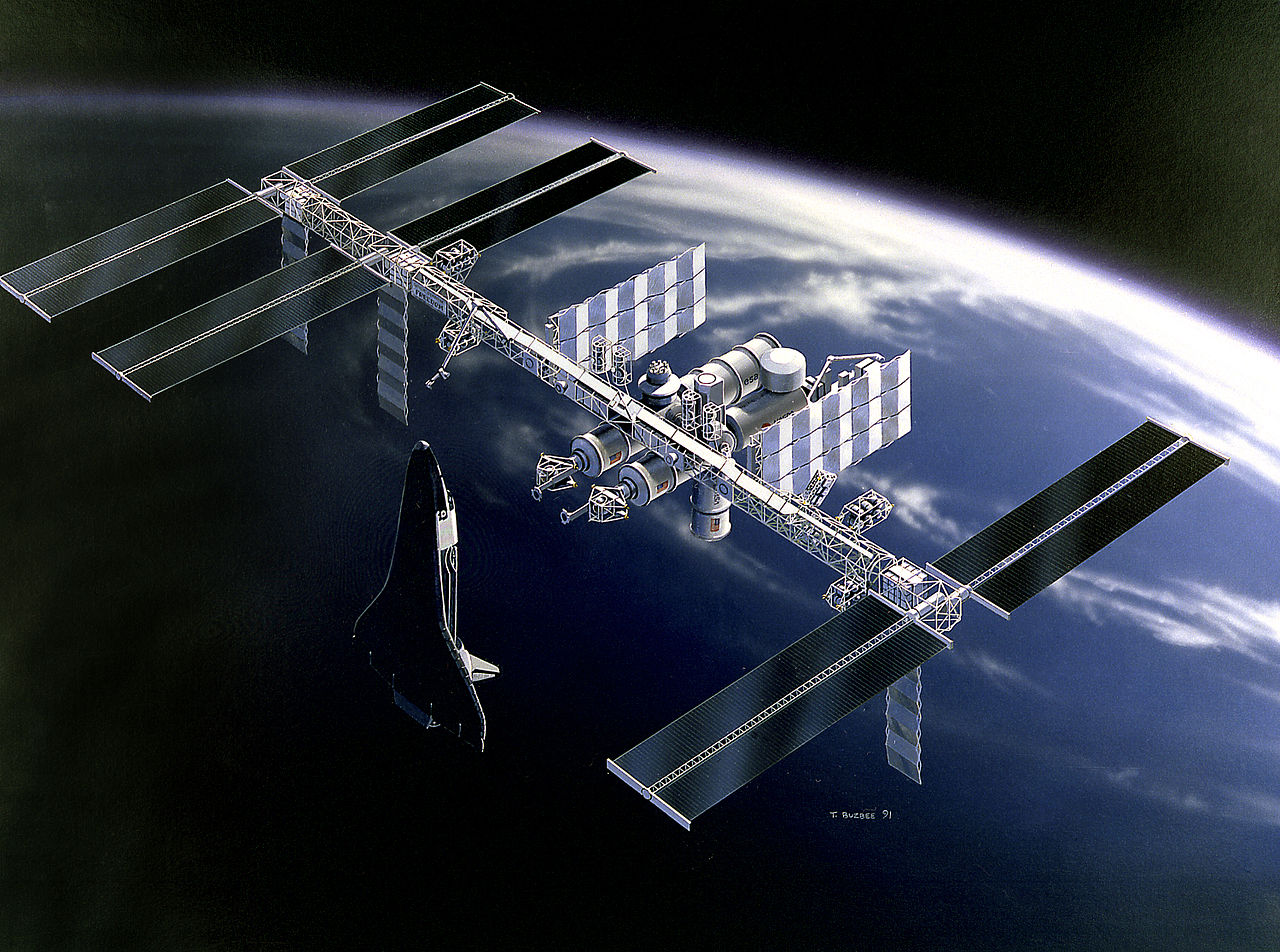

Twenty years ago, tomorrow, on 7 February 2001, shuttle Atlantis launched the U.S. lab Destiny to the International Space Station (ISS). Command and control hub, nerve-center for scientific research and formally since 2005 a U.S. National Laboratory, this 28-foot-long (8.5-meter) cylinder provided nothing short of the heart and brains for the largest and brightest human-made object in the sky.

Yet originally, there should not have been one Destiny, but two, for when President Ronald Reagan announced plans to build a permanent space station in January 1984, its early conceptual design featured two U.S. labs, a figure revised down to one lab in a major redesign after the January 1986 Challenger disaster.

By August 1988, in the spirit of Reagan-era politics, the station was named “Freedom”. And under the language of initial Intergovernmental Agreements (IGAs) between the United States, Japan, Canada and the member-states of the European Space Agency (ESA), about 97 percent of the lab’s resources were allocated to NASA and the remainder to Canada, in return for its contribution to building the station’s robotic assets.

By the early 1990s, the lab was due to be delivered on the sixth shuttle assembly mission and its arrival would herald Man-Tended Capability (MTC) on Freedom, with about half of its 24 payload racks devoted to research and the remainder allocated to Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS), Thermal Control System (TCS), Electrical Power System (EPS) and other operational needs. “The lab is really the guts of the space station’s research and command and control capabilities,” STS-98 astronaut Tom Jones told a NASA interviewer. “It becomes possible to do science and make the science “quality science”, because of the arrival of the lab.”

Following further redesigns of Freedom—and its eventual rebirth as the International Space Station (ISS)—the fabrication of the lab was completed by prime contractor Boeing in September 1995, with a targeted launch date in late 1998. It then underwent machining for various functions, including the drilling of holes for hatch seals and berthing mechanisms, followed by the installation of Micrometeroid Orbital Debris (MMOD) shield blankets and various mechanical systems, ahead of pressure testing and painting.

By the late spring of 1997, delays to the program had pushed the first launch of ISS hardware to no sooner than July 1998, which in turn pushed the U.S. lab about six months downstream. According to Tom Jones, in his memoir, Sky Walking, veteran astronaut Mark Lee approached him in the spring of 1997 to participate in underwater tests in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL), just to the north of the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas. “I didn’t want to get my hopes up,” Jones wrote, “but Mark seemed to be carrying around some good news, although he was not quite certain how to share it.”

Early in June 1997, NASA assigned Lee and Jones to train for three sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) to install the lab on shuttle mission STS-98, then planned for May 1999. The lab would be installed at the aft “end” of the Unity node, necessitating the robotic removal of Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2 from this interface.

Initial plans, crystallized by Lead EVA Officer Kerri Knotts, envisaged Lee and Jones wiring up the lab’s backup heaters to keep its electronics warm during the bitter orbital nighttime, then hooking up power, data and cooling umbilicals, together with a grapple fixture for the subsequent installation of the Canadarm2 robotic arm. Finally, the spacewalkers would assist in the robotic relocation of PMA-2 to its new location at the forward end of the newly-installed lab. “The EVAs were central to the success of the mission,” Jones wrote. “If we failed to get the job done, the lab could be irreparably damaged and the space station’s future research and control capabilities seriously degraded.”

Yet the delays—particularly in relation to Russia’s Zvezda service module—continued, with the launch of the first station elements postponed until the end of 1998. This pushed the flight of STS-98 and the lab until no earlier than October 1999. In anticipation of this revised schedule, in August 1998 NASA assigned Ken “Taco” Cockrell, Mark “Roman” Polansky and Marsha Ivins to round out the STS-98 crew, with the expectation that the Expedition 1 increment of Commander Bill Shepherd and his Russian comrades Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev would be aboard the ISS for the lab’s installation.

Within weeks, the Russian financial collapse factored into the late delivery of Zvezda, and STS-98 was pushed until no sooner than January 2000. And as circumstances transpired, the service module did not rise to orbit and dock at the ISS until July 2000, which shoved each successive shuttle assembly mission further downstream and moved STS-98 to no sooner than January 2001.

Although Zvezda’s eventual arrival “would break the assembly logjam and kick off a series of major construction milestones,” according to Jones, the makeup of his crew had also changed significantly. In September 1999, it was revealed that Mark Lee had been removed from the STS-98 crew, for undetermined reasons.

In Sky Walking, Jones expressed intense disappointment over the decision—Lee’s “leadership and hard work” in preparing for the mission, he wrote, “had been not only superlative but, to me, indispensable”—and the crew’s efforts to win a review of the situation from the Office of Space Flight at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., were fruitless.

Lee was replaced by veteran astronaut Bob Curbeam, who had himself been in training for more than two years in support of another mission. “Beamer and I had never worked together,” Jones recalled, with their respective duties and previous missions having “kept us from being more than nodding acquaintances,” although Curbeam blended seamlessly into the crew. In fact, it was Curbeam who proposed attaching the main power and cooling umbilicals onto Destiny during the first EVA, thereby pushing the lab’s activation two days earlier than planned.

As a consequence, Jones now assumed the role of “EV1”, the chief spacewalker, for STS-98 and as launch neared he and Curbeam averaged about 200 hours performed underwater training in the NBL. And with the resumption of ISS construction on the STS-92 and STS-97 missions in the fall of 2000—together with the arrival of Expedition 1 to begin the permanent occupation of the outpost—the stage was set for the arrival of the U.S. lab, which had by now received the name “Destiny”.

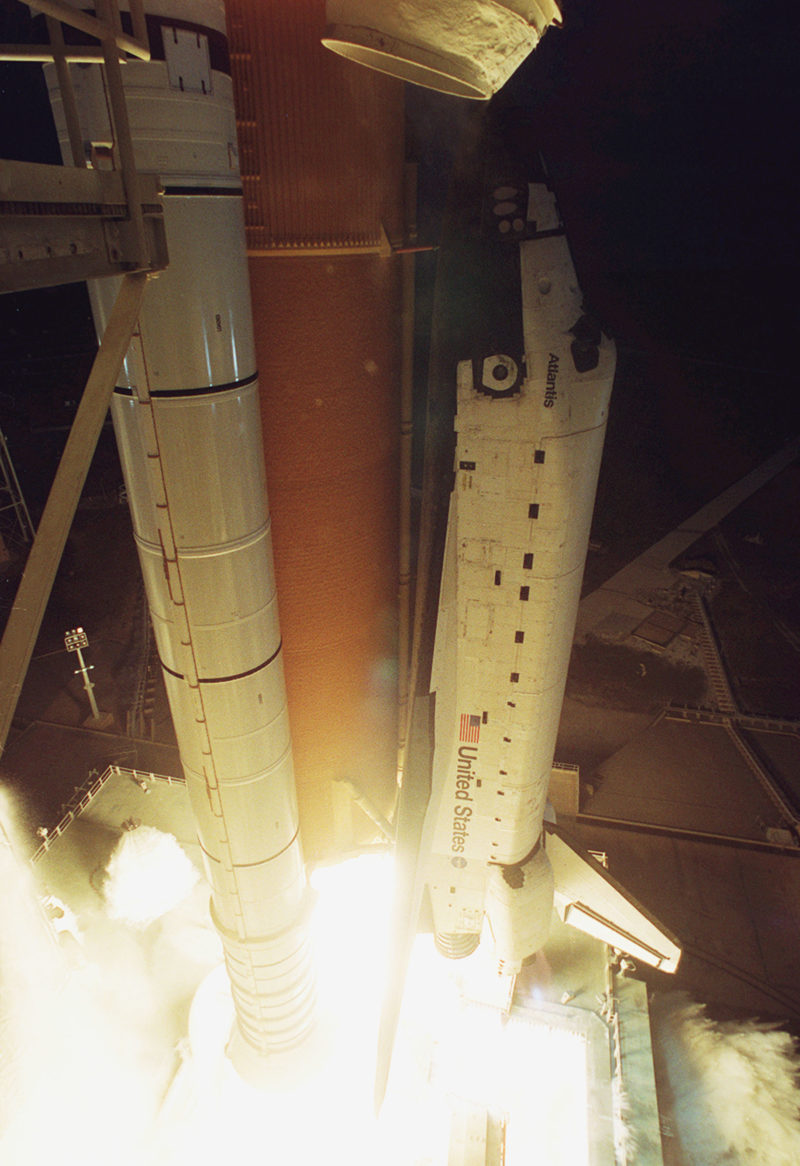

Originally targeted to launch on 18 January 2001, the need to resolve a problem associated with the separation ordnance of the left-hand Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) delayed the rollout from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to Pad 39A. The wiring was X-rayed and revealed crumbling electrical cable shielding, which was repaired without the need to de-stack the vehicle, but postponed the launch until later in January.

At length, after also weathering a computer malfunction within the Mobile Launch Platform (MLP), the shuttle arrived at Pad 39A on the 3rd. Unfortunately, more trouble was afoot, as assessments of the SRB separation ordnance issue prompted a decision to roll the stack back to the VAB for testing to confirm the health of the wiring. This pushed the launch to early February, with managers eventually settling on the 7th.

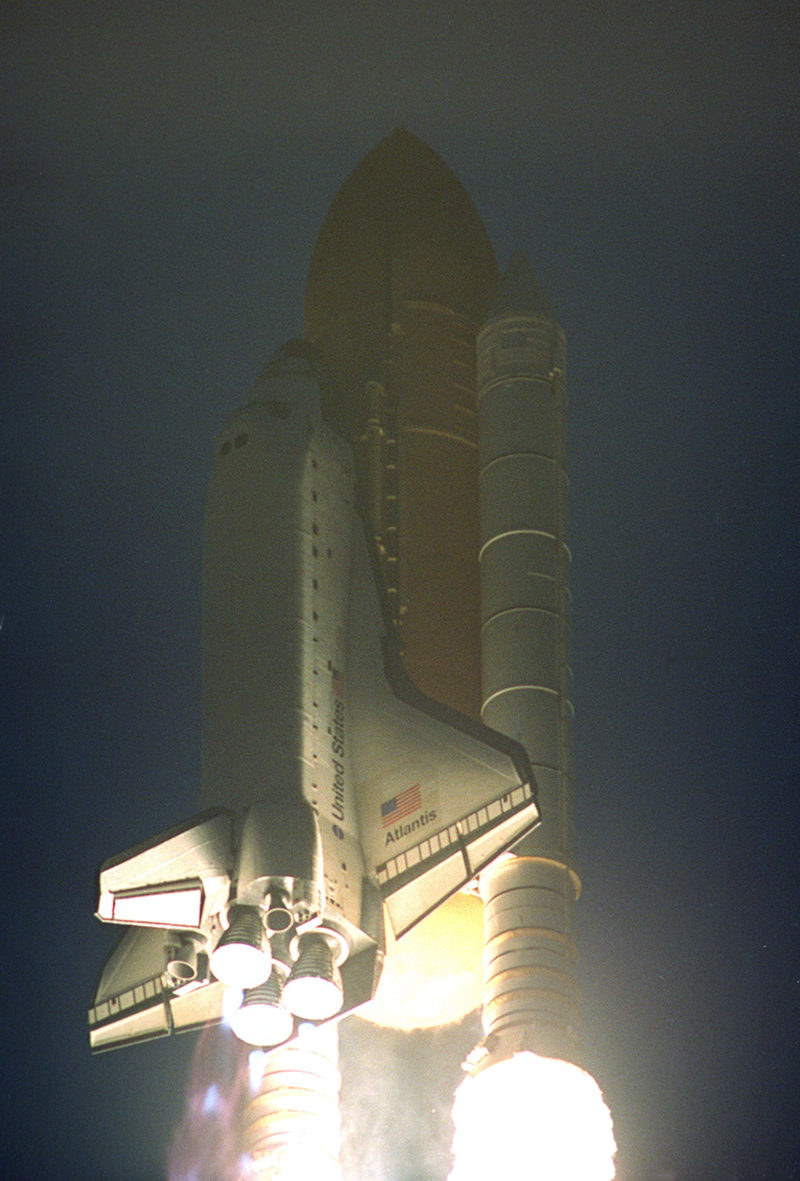

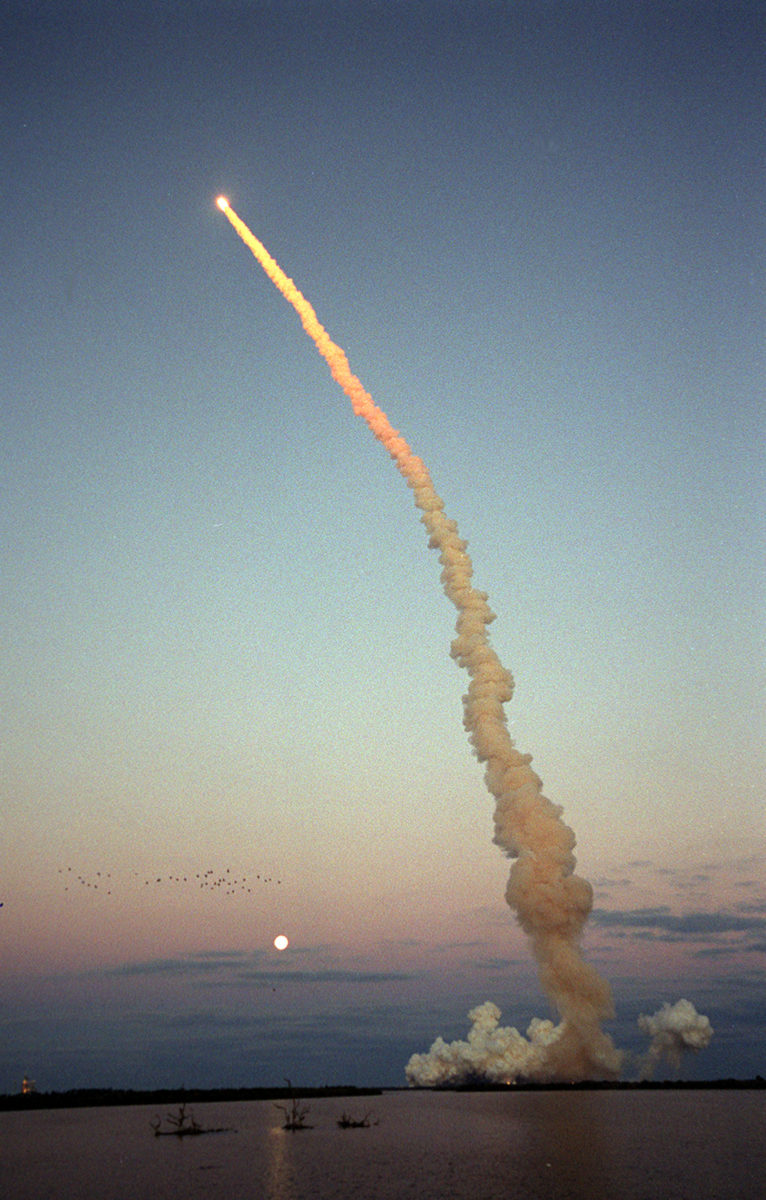

Liftoff occurred a few minutes after local sunset, at 6:13 p.m. EST—coincidentally on the Expedition 1 crew’s 100th day in space—and lit up the darkened Florida sky as Atlantis speared for the heavens on a two-day chase of the space station.

“Atlantis surged upward, the bag and rattle settling into a more tolerable, yet still pronounced shaking,” Jones wrote. “Atlantis began to rotate onto the proper track to chase the ISS up the East Coast. I felt the orbiter pirouette gracefully, swing past the mark, then gently correct the overshoot. Heads down now, we arced over the Atlantic; my body slid tightly against my shoulder straps and stayed there.”

Riding the “full-throated scream” of the SRBs for the first two minutes, the stack also endured the “rising howl” of the slipstream passing Atlantis’ walls and the “pulsing vibration” of the shuttle’s three main engines, before the five astronauts achieved their initial orbit just 8.5 minutes after departing the Cape.

Throughout the first two days, Cockrell and Polansky executed a series of rendezvous “burns” to draw closer to the space station and by the early hours of 9 February the pilots pressed into their final procedures as Atlantis reached just 9 miles (15 km) from its destination.

At 11:51 a.m. EST, Cockrell performed a smooth docking at the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-3 interface, located at the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Unity node. This was the second such docking at PMA-3, and Cockrell was required to adopt a “tail-forward” attitude—with Atlantis’ nose directed along the station’s long axis—thereby creating the proper conditions for the installation of Destiny.

Atlantis and her five astronauts were briefly welcomed by the station’s incumbent Expedition 1 crew, before the hatches were closed in readiness for the first of three challenging EVAs by Jones and Curbeam. Early on 10 February 2001, Ivins used the shuttle’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm to remove the PMA-2 docking adapter from the forward “end” of Unity, in order to make room for the installation of the Destiny lab.

Assisted by visual cues from Jones, Ivins “temp-stowed” PMA-2 onto the station’s nascent truss. It marked the start of a joint EVA/robotics operation which would characterize the rest of the mission.

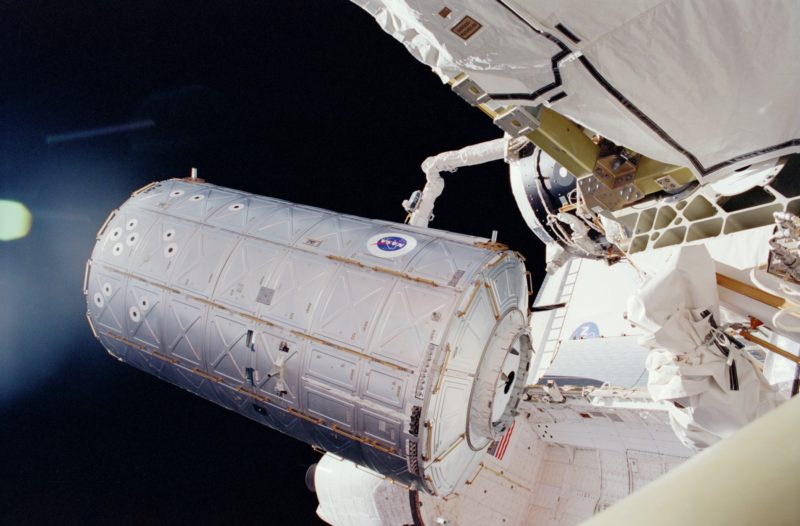

As Jones assisted Ivins, Curbeam removed protective launch covers and disconnected electrical power and cooling umbilicals between Destiny and the shuttle. At 12:23 p.m. EST, Ivins grappled Destiny with the RMS and raised it from the payload bay, “flipping” it 180 degrees and aligning it for a smooth attachment to the Unity forward port at 1:57 p.m., where it was bolted into its permanent home.

In a stroke, the work increased the space station’s habitable volume by about 3,800 cubic feet (107.6 cubic meters) to a total of more than 13,000 cubic feet (368 cubic meters) and expanded the living quarters of Shepherd’s crew by 41 percent. With the 32,000-pound (14,500-kg) lab in place, Jones and Curbeam set to work connecting electrical, power, and data cables.

Their work ran smoothly, with the exception of a small ammonia leakage as Curbeam was installing a cooling umbilical. This prompted flight controllers to impose a decontamination procedure, in which Curbeam remained in direct sunlight for 30 minutes and Jones brushed down his suit and equipment. When the duo returned to Atlantis’ airlock, they performed a partial repressurization, in order to flush out any flakes of ammonia, before commencing a final repressurization and subsequent ingress into the orbiter.

Due to the extended decontamination effort, EVA-1 lasted more than 7.5 hours, some 60 minutes longer than intended, but had positioned the STS-98 and Expedition 1 crews favorably to begin activating Destiny’s systems. Later that day, Cockrell and Shepherd began remotely powering up the lab, via laptop computers, with ground controllers continuing this effort through the night.

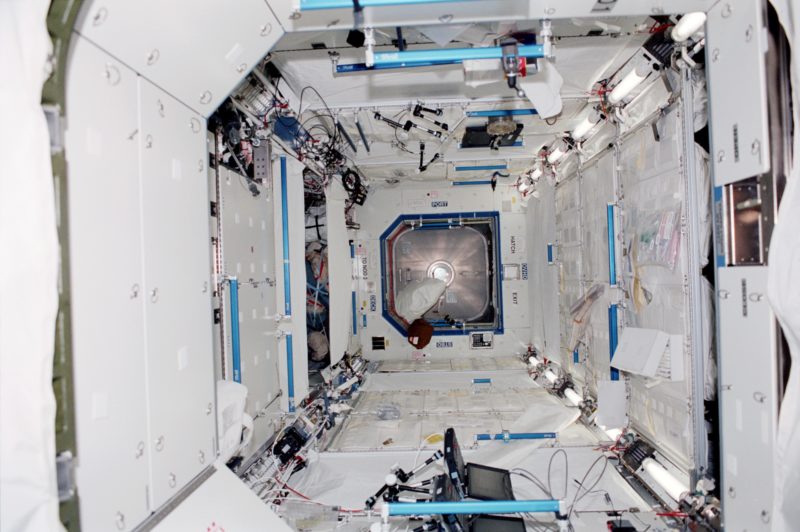

Next morning, at 9:38 a.m. EST, the two commanders opened the hatches and entered Destiny for the first time. Thus began a busy schedule to activate air conditioners, fire extinguishers, computers, internal communications systems, electrical outlets, ventilators, alarms, and air-purification equipment. In order to save weight, the lab was launched with only five of its eventual 24 payload racks in place, and it was a relatively spacious, though spartan, module in which the astronauts and cosmonauts worked.

Jones and Curbeam’s second EVA got underway at 10:40 a.m. EST on 12 February and saw them again functioning in tandem with RMS operator Ivins. The spacewalkers provided visual assistance as Ivins detached PMA-2 from its temporary perch on the station’s truss and maneuvered it to its new position at the forward end of Destiny, where it would provide the primary docking interface for shuttle visitors, until the arrival of Node-2.

With this significant task completed, Jones and Curbeam installed insulating covers over Destiny’s launch restraint pins, installed air vents, wires, handrails, and sockets, and were able to press ahead into several tasks originally planned for EVA-3: connecting computer and electrical cables between PMA-2 and the lab, removing covers from Destiny’s high-quality window, and attaching an external shutter.

After almost seven hours outside the ISS, the astronauts returned inside Atlantis, as flight controllers began commanding the four Control Moment Gyroscopes (CMGs) on the Z-1 truss. Installed the previous year as a means of managing the station’s orientation, they were to be directly controlled through electronics inside Destiny itself.

“For command and control, right now, we’re in sort of a crude mode, where we use thruster control to maintain attitude on the space station, and that’s a very propellant-intensive activity,” explained Jones before the flight. “We want to get the gyros…to control the station’s attitude and the software and commanding … that make that possible, are all in the lab. That enables a more fuel-efficient mode of operation, which permits maintaining attitude control with momentum wheels. The Control Moment Gyros are much less disturbing to a microgravity environment than thruster firings are, so that makes a good-quality research environment available on the station.”

This important work was accompanied by “command authority” testing, throughout the week, as the lab’s newly-activated computers were verified as being capable of taking over orientation control from the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS). “The gyros were operating perfectly,” NASA reported on 13 February, “displaying good speeds and normal temperatures as they worked to gently steer the station to provide correct alignment of the U.S. and Russian module solar arrays to the Sun.”

Significantly, Jones and Curbeam’s third and final EVA on 14 February was initially touted by NASA as the 100th spacewalk in U.S. history—blazing a trail which had begun almost 36 years earlier, in the pioneering excursion of Ed White—and the astronauts were tasked with installing a spare S-band communications antenna onto the Z-1 truss, photographing the newly-arrived P-6 photovoltaic arrays, and performing practice efforts for future rescue techniques.

“Beamer and I planned to say a few words to honor those spacewalking pioneers before us,” Jones reflected in Sky Walking, but this was arrested by a call from Mission Control. Apparently, a recount had been done and concluded that the real 100th U.S. EVA had occurred during their second spacewalk on the 12th. Presenting the note through the aft flight deck window to the astronauts, Polansky told Jones and Curbeam that the message had been conveyed privately, “so we didn’t have egg on our face if somebody checks the numbers.”

NASA’s official news release noted that the astronauts “completed their third and final planned spacewalk,” after almost 5.5 hours, before “pausing to celebrate the mission, which included the 100th spacewalk in United States space history.” Jones and Curbeam displayed a placard to commemorate those EVAs, which occurred from Gemini and Apollo spacecraft, as well as from the shuttle and the Skylab space station, and upon the surface of the Moon. “This achievement, this golden anniversary, so to speak, is a tribute to all the people who have done spacewalks,” Curbeam said. “And we salute all of you and appreciate your hard work and thank you so much.”

However, the 100th-EVA mystery was “one last curveball” to be thrown at the crew, Jones recalled, but although he alluded nothing of significance to the event, it has been pointed out over the years that the apparent “miscount” could reflect an EVA which was performed, but never formally acknowledged. One such candidate was the classified STS-27 mission in December 1988, during which the crew rendezvoused with their just-deployed spy-satellite payload and conducted repairs. Whether these “repairs” included a spacewalk has never been divulged, but it has been offered as one possible explanation.

With Destiny having been installed and activated, the STS-98 crew undocked from the space station and returned safely to Earth on 20 February 2001. Yet their contribution, aside from when the 100th U.S. EVA actually took place, is enormously significant, for the expansion of the ISS very much hinged on the success of their mission.

“I try not to dwell too much on the specific significance for our flight, because it’s going to be overshadowed by the significance of the next flight,” said Cockrell in his pre-launch interview. “And they’re all important and each flight is critical to the next flight.” That said, Cockrell was keenly aware that getting Destiny activated was necessary in order for the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, to assume primary command and control of the ISS from Russia.

The lab’s role over the last 20 years has seen it provide support for hundreds of experiments in life and microgravity sciences and applications, as well as serving as the central hub for commanding ISS robotic assets and enabling the installation of station hardware and the rendezvous and berthing of visiting vehicles. In September 2002, the role of “science officer” was created in response to the increased emphasis upon research which Destiny’s arrival had enabled and the 2005 NASA Authorization Act designated the unique facility as a “U.S. National Laboratory.”

Under the language of the Act, NASA was directed to “increase the utilization of the ISS by other Federal entities and the private sector,” in the advancement of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. And in September 2011, NASA finalized a co-operative agreement with the independent, non-profit Center for the Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS) to manage the lab. As it enters its 21st year of operational service, and with a crew of seven now aboard—including four U.S. Operational Segment (USOS) crew members—the future importance of Destiny through the 2020s seems secure.

Hi Ben,

I couldn’t have written it better myself. Thank you for the excellent summary of the good work of the combined crews–STS-98, Expedition 1, and flight controllers–that enabled Destiny to begin her life in orbit and serve successfully for so long. Destiny’s designers and builders put together an amazingly reliable and long-lived facility. It’s a pleasure to see Expedition 64 hard at work in Destiny today.

With thanks,

Tom Jones

STS-98 MS-3, EV-1