As the United States readies itself for the launch of an entirely new space vehicle next week—the long-awaited voyage of the Demo-2 Crew Dragon, carrying NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken—today also marks 20 years since a (virtually) brand-new spacecraft roared aloft on a mission to kickstart the assembly the International Space Station (ISS) and prepare it for its first human visitors. By 19 May 2000, shuttle Atlantis had been on the ground for more than two years, undergoing over a hundred modifications, including the installation of the Multifunction Electronic Display System (MEDS) to upgrade her vintage 1970s-era flight deck instrumentation with a more modern flat-panel “glass cockpit”. It was no accident, then, that as this good-as-new ship rose from Earth at 6:11 a.m. EDT for her 21st mission, she was heralded as “a Space Shuttle for the 21st century”.

When the STS-101 crew was announced in November 1998, they were expected to launch after the arrival of Russia’s Zvezda service module and continue its internal and external outfitting. Commander Jim Halsell would lead pilot Scott “Doc” Horowitz and mission specialists Mary Ellen Weber, Ed Lu and future U.S. spaceflight endurance record-holder Jeff Williams. Three months later, in February 1999, Russian cosmonauts Yuri Malenchenko and Boris Morukov were added as mission specialists. Originally scheduled to fly in August 1999, a combination of ISS Program delays and electrical wiring problems across the shuttle fleet pushed their launch firstly to December and then into April 2000.

By this time, the long-delayed Zvezda had been delayed to July 2000 and it became clear that Halsell’s crew would actually launch before its arrival. Accordingly, the astronauts were split into two new crews—STS-101 in April, led by Halsell, and STS-106 in August, led by veteran shuttle commander Terry Wilcutt—to better distribute critical mission tasks before and after the module’s arrival. Halsell retained Horowitz, Weber and Williams and picked up veteran NASA astronauts Jim Voss and Susan Helms, together with Russian cosmonaut Yuri Usachev, who were deep into training for the second ISS expedition. Meanwhile, Lu, Malenchenko and Morukov were shunted onto the downstream STS-106 flight.

Liftoff of STS-101 was targeted for 24 April, but the mission seemed snakebitten by misfortune right from the start. Atlantis’ Ku-band antenna suffered accidental damage in the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) in March, then one of her main engines required replacement after concerns about the health of nickel-alloy tips in the high-pressure hydrogen turbopump, a rudder speed brake needed replacement at Pad 39A and Halsell himself succumbed to a sprained ankle during training.

Ill-fortune, however, was quite done with STS-101. Two launch attempts on 24 and 25 April were scrubbed due to unacceptably high winds at the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF), whilst a third on the 26th came to nothing following poor weather at the Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) sites at Zaragoza and Moron, both in Spain.

NASA and the Eastern Range now faced the possibility of a lengthier delay. Three expendable vehicles—an Atlas IIA with a Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES), a Titan IVB laden with a Defense Support Program (DSP) early-warning satellite and a Delta II carrying a Global Positioning System (GPS) Block IIR—were expected to fly from three different pads at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., in the early-to-mid-May timeframe, threatening to push STS-101 to at least the 18th. Those missions all flew as planned, but the scheduling waters were muddied yet further by the inaugural launch of the Atlas IIIA, carrying the Eutelsat W4 communications satellite. As the first flight of a new vehicle, it was granted three back-to-back launch attempts by the Eastern Range and having missed its first try on 15 May the STS-101 liftoff was correspondingly pushed back another 24 hours to the 19th.

As circumstances transpired, the Atlas IIIA was kept on the ground by bad weather and eventually flew on 24 May. This provided a good opportunity to get Atlantis off the ground and she duly speared into orbit at 6:11 a.m. EDT on the 19th. Flying at dawn proved spectacular not only for onlookers lining the Space Coast, but also for the crew. Horowitz recalled later that it was “hard to read your displays” during first-stage flight, but added that the separation of the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) was a “glorious” sight. “They say good things come to those who wait,” Launch Director David King told journalists after launch. “We waited for a while on this one, but the satisfaction is immense. And what a beautiful time of day to launch; the vehicle going into the sunrise on ascent was awesome.”

Only the most minor of glitches characterized Atlantis’ early hours in orbit, when one of two propellant valves for the left-hand Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) stubbornly refused to close. Its backup valve functioned normally, but the engine—though it remained in good health—was deselected for the rest of the mission. It would not be used again until its critical role in the deorbit “burn” to bring Atlantis home. In the meantime, NASA explained that the rendezvous burns could be accomplished with the right-hand OMS engine.

Heading for a docking at the space station on 21 May, the pilots busied themselves with the rendezvous checklist and the rest of the crew worked to check out the shuttle’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm and set up the space suits for a planned session of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) by Williams and Voss.

The Terminal Initiation (TI) burn put the shuttle on a course directly towards the ISS to a position about 600 feet (180 meters) “below” the station, which at that time was 76 feet (23 meters) in length and comprised the Russian-built Zarya control module and the U.S.-built Unity node, the latter launched aboard shuttle Endeavour in December 1998. Halsell then took command of his ship and deftly guided Atlantis through a half-circle to pass in front and “above” the ISS to effect a docking high above Central Asia at 12:31 a.m. EDT on 21 May.

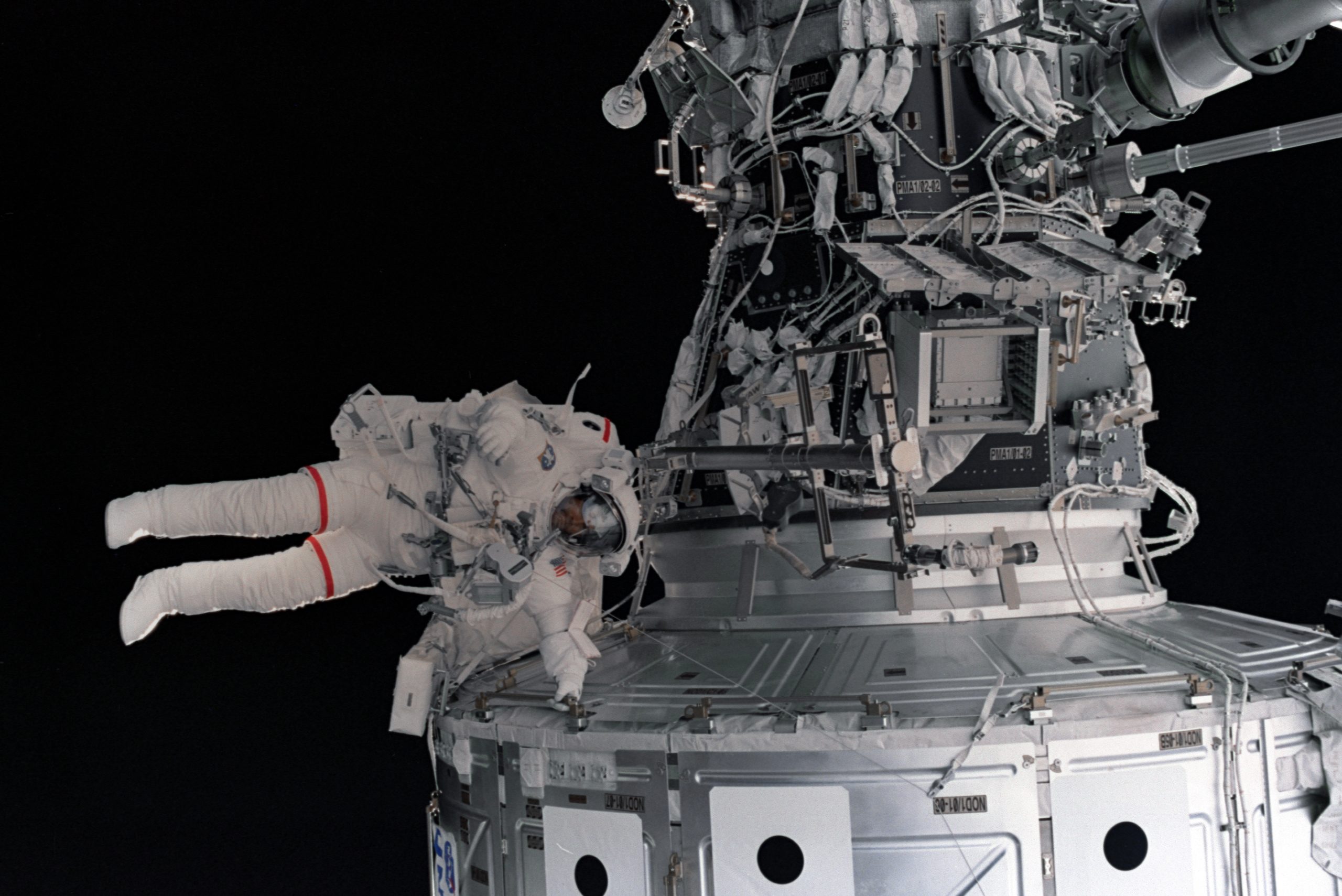

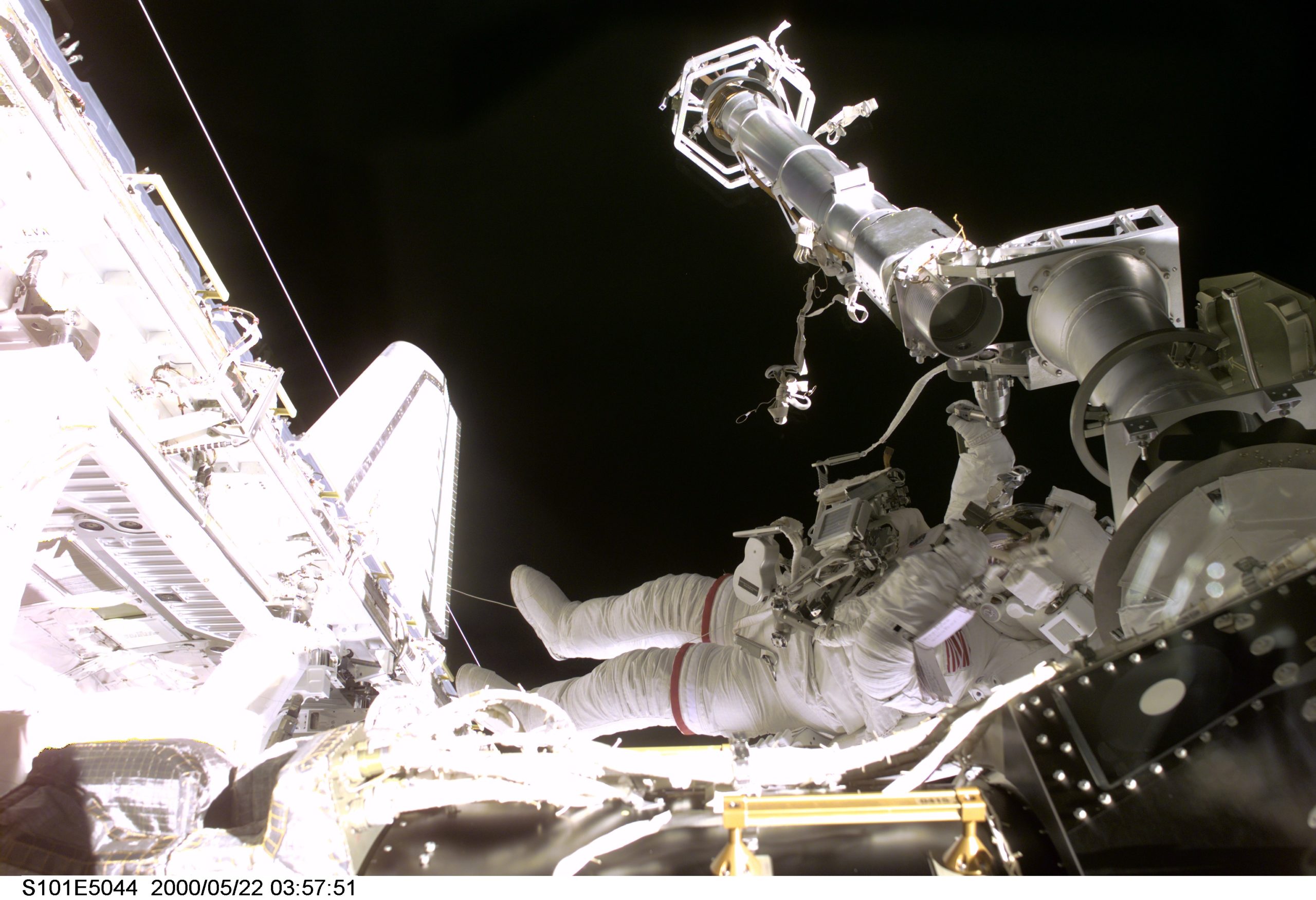

Immediately after docking, the cabin pressure was lowered from an ambient 14.7 psi down to 10.2 psi to enable Williams and Voss to properly purge nitrogen from their bodies ahead of their spacewalk. The primary tasks of the EVA—the fifth conducted in support of ISS construction and maintenance—involved the men inspecting and securing a 209-pound (95 kg) U.S.-built crane, installed the previous year, and completing the assembly of Russia’s Strela (“Arrow”) cargo crane.

With Voss anchored to a foot restraint at the end of the RMS, and Williams free-floating, the spacewalkers remained ahead of the timeline throughout their excursion. Veteran spacewalker Voss later described riding the robot arm as “the best form of public transportation in the world”, whilst first-timer Williams described it as “a crew-intensive activity” and “certainly the highlight of the mission”. During their six hours and 44 minutes outside, the astronauts also replaced one of Unity’s early communications antennas, which had exhibited trouble, and installed several handrails and a new camera cable.

With the EVA done, the complex process of entering the space station got underway late on 22 May. Over the course of nearly an hour, five hatches were sequentially opened to allow the crew to gain access to their new home for the next five days. And those five days were jam-packed with activity. In Atlantis’ payload bay, a Spacehab double cargo module was laden with cargo and equipment from sewing kits to clothing, a stationary bicycle ergometer and four large bags of drinking water. Tools, books, notepads, trash bags and can openers were also among a comprehensive inventory of goods moved over to the station in readiness for the arrival of the first long-duration crew, Expedition 1, in late 2000.

Astronauts on the most recent mission to the ISS in June 1999 had complained of headaches and other ailments due to poor air quality and circulation within the complex. The STS-101 crew took air samples and monitored carbon dioxide levels, before rerouting and strengthening air ducts to improve airflow, adding acoustic mufflers and swapping out filters. They replaced four of Zarya’s six storage batteries, which had suffered from performance issues after more than a year in space. New fire extinguishers, smoke detectors and cooling fans were installed and Halsell and Horowitz fired the shuttle’s thrusters multiple times over three days to raise the ISS altitude by 27 miles (43 km) and establish it in an optimum configuration for the arrival of Zvezda in July 2000.

At 7:03 p.m. EDT on 26 May, Halsell undocked from what Lead ISS Flight Director Paul Hill described as “a pristine International Space Station” to begin the journey home. All told, Atlantis had remained docked for a few hours shy of six full days. And if the effort to get STS-101 into space had seemed snakebitten, her return to Earth proved quite the reverse, with Halsell bringing his ship to a smooth touchdown at 2:20 a.m. EDT on 29 May, on the very first landing opportunity of the day. The ghostly, pre-dawn touchdown on the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) brought to a close a mission that traveled in excess of four million miles (6.5 million km) and 155 orbits of Earth.

Although Atlantis’ return to flight 20 years ago today did not, strictly speaking, mark her “first” mission, STS-101 certainly showcased the veteran orbiter in a good-as-new capacity and her 130 modifications included not only the MEDS cockpit upgrade, but also significant weight reductions through the replacement of thermal-protection blankets and crew seats and enhancements to her navigation systems. And as the United States prepares to see an all-new human-capable space vehicle take to the Florida skies on 27 May, we are reminded that Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken’s destination—the International Space Station—came to be, in no small part, thanks to the efforts of STS-101 all those years ago.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.