After more than ten years in development, the world’s largest and most powerful rocket sits on Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Standing over 322 feet (98 meters)—taller than the Statue of Liberty rises from ground level to the tip of her torch—NASA’s colossal Space Launch System (SLS) rolled the 4.2 miles (6.7 kilometers) from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to the pad overnight Tuesday/Wednesday.

“First motion” occurred shortly after 10 p.m. EDT Tuesday and the stack was declared “hard-down” on the pad a little past 7:30 a.m. EDT Wednesday. If all goes well, the SLS will now enjoy a 12-day pad processing regime, ahead of liftoff no sooner than Monday, 29 August. The launch “window” extends from 8:33 a.m. through 10:33 a.m. EDT.

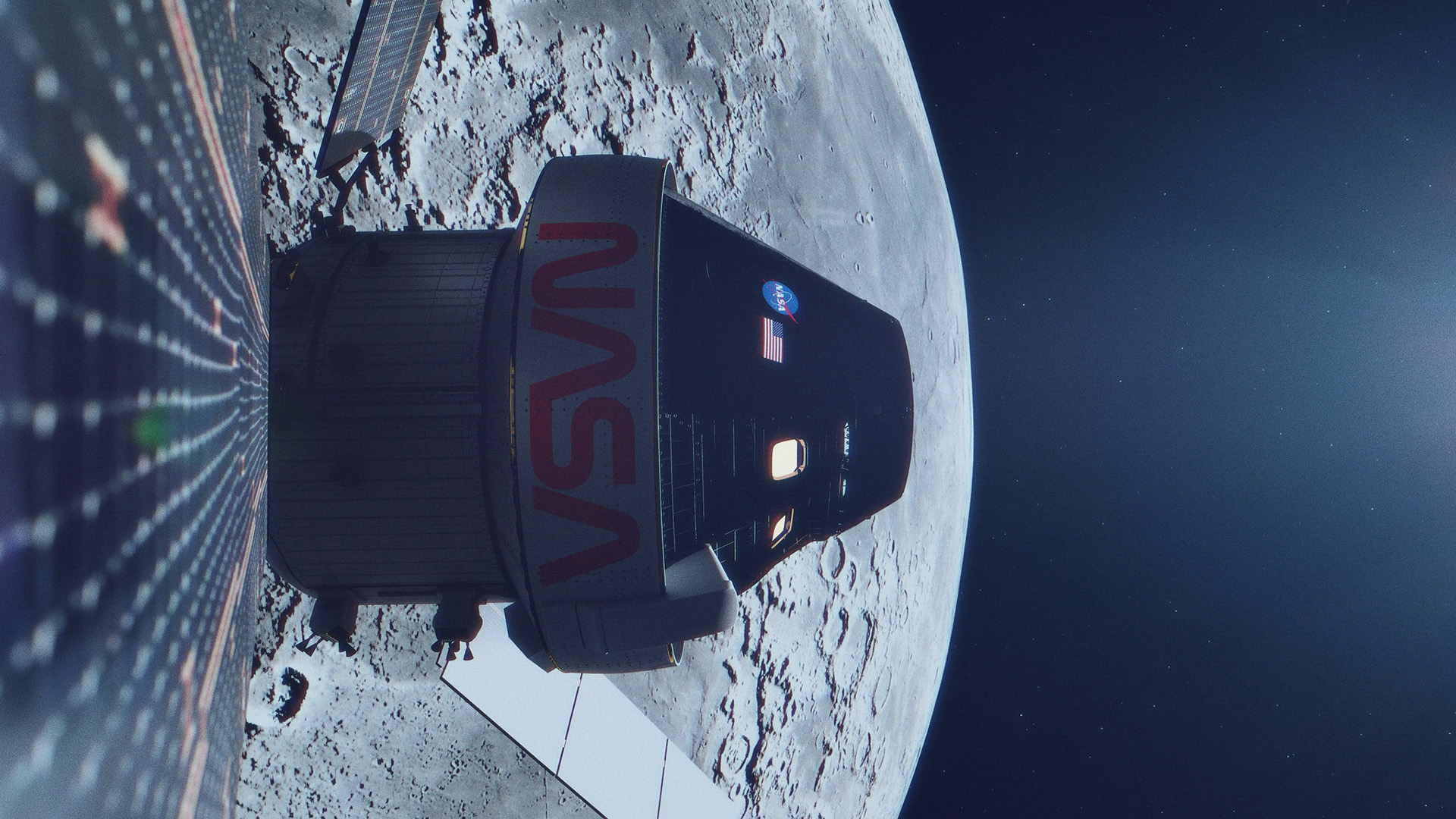

The Artemis-1 mission is slated to run for six weeks, delivering an uncrewed Orion spacecraft around the Moon and marking the first voyage to lunar distance by a human-capable vehicle since Apollo 17, way back in December 1972. Its success will set the stage for Artemis-2, scheduled for no sooner than fall 2024, which will mark the first crewed mission to the Moon in over a half-century.

According to NASA Chief Astronaut Reid Wiseman, crew assignments for Artemis-2 are anticipated later this year. The four-member crew will include a Canadian astronaut.

Earlier in August, NASA officially unveiled three possible No Earlier Than (NET) launch opportunities for Artemis-1. The first would enjoy a spacious two-hour “window”, opening at 8:33 a.m. EDT on 29 August, producing a nominal 42-day flight for Orion and a return to Earth and splashdown on 10 October.

The second, also with a two-hour window, would shake the Florida ground at 12:48 p.m. EDT on 2 September, would see Orion return home on 11 October. And the third, launching at 5:12 p.m. EDT on 5 September, at the start of a slightly truncated 90-minute window, would envisage a mission duration extending through 17 October.

Artemis-1 will also be the 60th launch from Pad 39B. Unveiled more than five decades ago, the pad saw a single Saturn V fly in May 1969 with Apollo 10 astronauts Tom Stafford, John Young and Gene Cernan. Their eight-day mission to the Moon was an all-up dress rehearsal for the first crewed lunar landing.

The pad then supported the last four Project Apollo missions between May 1973 and July 1975, launching nine astronauts to America’s Skylab space station and three others on a joint venture with the Soviet Union. More than a decade then passed before 39B re-entered service—now as a shuttle-era facility—in early 1986.

But its return was blighted by tragedy, as its first resident was the ill-fated STS-51L, the final voyage of Challenger. From STS-26 in September 1988 through STS-116 in December 2006, the pad supported another 52 shuttle launches after Challenger.

That long list included three return-to-flight missions, the deployment of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), the return to space of “Original Seven” Mercury astronaut John Glenn and the launches of the Magellan, Galileo and Ulysses deep-space probes. After its final shuttle use in the winter of 2006, Pad 39B was repurposed for the Constellation Program, which saw just a single launch—the Ares I-X test flight—back in October 2009.

And the SLS arose from the never-flown Ares V super-heavylift booster, which might have returned Americans to the Moon under President George W. Bush’s ill-fated Constellation Program, prior to its cancelation by the Obama Administration in April 2010. A year later, in September 2011, the SLS came into being.

Over the next decade, this multi-billion-dollar behemoth moved agonizingly from design to hardware to testing and finally to the pad. It passed its Preliminary Design Review (PDR) in August 2013 and its Critical Design Review (CDR) in October 2015, which cemented its architecture as an “evolvable” vehicle powered by four shuttle-heritage RD-25 engines to lift its 212-foot-tall (64.6-meter) Core Stage and a pair of five-segment Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), each standing 177 feet (53.9 meters) high.

Five Structural Test Articles (STAs) of the giant rocket’s upper section, liquid hydrogen tank, liquid oxygen tank and engine section underwent 199 tests and gathered 421 gigabytes of data for SLS computer modelers. Engine section tests to evaluate thrust loads and “outward” forces impaired by the SRBs began in spring 2017 and were completed early the following year. These tests helped inform the liquid oxygen tankage design by validating the performance of feedline brackets.

Next up, the STA for the rocket’s liquid hydrogen tank—its biggest single component, at 149 feet (45.4 meters) long—was put through an aggressive test campaign, which intentionally brought it to the brink of structural failure. In parallel, the liquid oxygen tank was also subjected to stresses many times higher than it will ever experience in flight, tested via a crippling cocktail of compression, tension, bending, torsion and sheer stressors to virtual destruction in June 2020.

With STA testing complete, attention turned to the “Green Run” test campaign in the B-2 Test Stand at NASA’s Stennis Space Center (SSC) in Bay St. Louis, Miss. In August 2019, a “pathfinder” of the SLS Core Stage was put through initial fit checks, before the “real” Core Stage for Artemis-1—standing 212 feet (64.6 meters)—arrived at Stennis in January 2020 for the eight-test Green Run.

Despite the ravages of the coronavirus pandemic and the depredations of Mother Nature which hampered progress, the Green Run was conducted throughout 2020 and into the spring of last year. It concluded with a successful full-flight-duration test-firing of the four RS-25 engines, lasting more than eight minutes, in March 2021. A few weeks later, the Core Stage arrived on the Space Coast for processing.

In the meantime, other SLS hardware elements had already begun to arrive in Florida, including the ten segments for the two SRBs in June 2020. Stacking of those segments in High Bay 3 of the iconic VAB took place between November 2020 and March 2021.

Following the arrival in Florida of the Core Stage, it was lowered into position between the two boosters in June. Next, the tapering Launch Vehicle Stage Adapter (LVSA) was mounted atop the Core Stage, raising the height of the rocket to 25 stories.

By early July 2021, the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS)—whose RL-10 engine, built by Aerojet Rocketdyne, will conduct the Translunar Injection (TLI) “burn” to deliver the Orion spacecraft out of Earth orbit and on course for the Moon—was added to the stack. And the Orion Stage Adapter (OSA) was set in place last October.

All that remained was Orion itself and its Launch Abort System (LAS). Having attached the LAS and four protective “ogive” fairing panels onto Orion last summer, the finishing piece of Artemis-1 was in place last 20 October.

Integrated testing followed over the winter and the SLS was rolled out of the VAB for an 11-hour crawl to Pad 39B on St. Patrick’s Day, 17 March. But hopes of having the luck of the Irish on its side were ominously absent, for the two-day Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR) at the pad—which aimed to fuel the giant rocket with over 700,000 gallons (3.2 million liters) of cryogenic oxygen and hydrogen—seemed jinxed from the outset.

Four lightning strikes and multiple technical difficulties prompted managers to call off the first WDR in mid-April and return the stack to the VAB for repairs. The giant rocket was back inside the cavernous interior of the assembly building on 26 April.

Returning to Pad 39B in the first week of June, efforts to “tank” the rocket with cryogens hit an early obstacle in the form of a hydrogen leak in the quick-disconnect umbilical at the mobile launcher’s Tail Service Mast (TSM). For a second time, the SLS returned to the VAB on 2 July, where teams replaced a pair of seals on the quick-disconnect assembly, repaired a fist-sized collet which had worked its way loose and installed flight batteries for the SRBs, ICPS and Core Stage.

Earlier this week, NASA announced that it was targeting the evening of Tuesday, 16 August—a couple days sooner than intended—to roll the SLS out to Pad 39B for the final time before launch. “First motion” of the stack occurred shortly after 10 p.m. EDT.

The stack briefly paused just outside the VAB high-bay doors to permit teams to reposition the Crew Access Arm (CAA). After nearly ten hours in transit, the SLS was declared “hard-down” on the launch pad a little past 7:30 a.m. EDT Wednesday.

Up next are validations of services, including command and control, data and telemetry, together with the extension of the CAA to permit access to the Orion spacecraft for final engineering and other tasks. The formal “Call to Stations” of Artemis-1 launch personnel, led by Launch Director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, is set to occur at 9:53 a.m. EDT Saturday, 27 August, with “tanking” of the Core Stage and ICPS early Monday 29th.

According to Ms. Blackwell-Thompson, in comments provided earlier in August, an additional hour of “hold” time has been built in the Artemis-1 countdown for added flexibility. Loading of more than 700,000 gallons (3.2 million liters) of liquid oxygen and hydrogen will begin with the Core Stage, then conclude with the ICPS.

An on-time launch on 29 August will see the four RS-25 engines and twin SRBs push the first SLS off Pad 39B with a combined impulse of around 8.8 million pounds (3.9 million kilograms). That represents about 1.1 million pounds (500,000 kilograms) extra liftoff muscle even than the Saturn V, which still stands as the largest and most powerful rocket ever brought to operational status.

Seven seconds after launch, the SLS will complete a computer-commanded “Roll Program” maneuver, not unlike that performed by the shuttle in yesteryear, to establish the vehicle on the proper flight azimuth for injection into low-Earth orbit. A minute into the mission, the giant rocket will pass through “Max Q”—a period of peak aerodynamic turbulence on its airframe—during which time the RS-25s will be throttled down, then back up to full power.

The two SRBs will be jettisoned a little over two minutes into the flight, at an altitude of almost 30 miles (48 kilometers) above Earth. Like their shuttle-era predecessors, the boosters will parachute towards the Atlantic Ocean, splashing down at 5.5 minutes after launch.

Meanwhile, the Core Stage will continue to burn, shutting down at 8.5 minutes and separating from the stack. This will leave the ICPS/Orion combo alone to begin the first voyage to the Moon with a human-capable vehicle in almost five decades.

Fifty-one minutes into the flight, the ICPS will conduct a Perigee Raise Burn to lift the “low point” of its orbit, before the main Translunar Injection (TLI) Burn about 97 minutes after launch. TLI is expected to be roughly an 18-minute firing of the RL-10 engine to push Orion out of Earth’s gravitational influence and onto a trajectory to rendezvous with the Moon.

It promises to be a mission for the history books. And for those of us—including this author—who were not born when humans last walked on the Moon, it will a poignant moment indeed. After a half-century, humanity stands on the brink of returning to deep space.

“Folks, we’re here,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, earlier this month, with characteristically dramatic flourish. “We are going back.”

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

Missions » SLS »

5 Comments

5 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:From Planning to the Pad: The Troubled Rise of Orion/SLS (Part 2) - AmericaSpace

Pingback:Weather Outlook Brightens at Start of Launch Window, as Teams Prepare for Artemis I - AmericaSpace

Pingback:Artemis I Scrubs, Teams Realign for Next Attempt NET Friday - AmericaSpace

Pingback:First SLS Flies, Turns Florida Night into Day - AmericaSpace

Pingback:First SLS Flies, Turns Florida Night into Day - Space News