For almost two decades, the United States and Russia have collaborated in the grandest scientific, engineering, and human endeavor ever undertaken in human history: the construction of the International Space Station (ISS). Since the days of the shuttle-Mir program, these two former superpowers—which once viewed each other with mistrust through the lens of differing political ideologies—have forged an enduring partnership. It has not been an easy journey and down-to-Earth politics has often strained relations, but it seems likely to continue. Yet the seeds of this partnership were first sown way before shuttle-Mir and the ISS, back in the early 1970s, when America and the then-Soviet Union emerged for the briefest of times from the “deep cold” of the Cold War and staged a manned space mission together, 40 years ago, this month. It was known as the “Apollo-Soyuz Test Project” (ASTP).

In January 1973, two years before launch, the two crews were identified. Aboard the Soviet Soyuz 19 would be Alexei Leonov—the world’s first spacewalker—and Valeri Kubasov, whilst the American Apollo 18 craft would be manned by Tom Stafford, Vance Brand, and Deke Slayton. The joint mission received more than its fair share of praise and criticism and preparation was rendered difficult, not least due to the enormous gulf between the cultures of East and West. Language was only one issue on the table. The astronauts and cosmonauts were not expected to be conversational or even fluent, but functional. At one press conference, when asked about the language barrier by a journalist, Stafford responded in Russian and Leonov translated it into English. Still, a few linguistic problems remained: the English would “maneuver” sounded like “manure,” whilst to the Americans the Russian word for “separate” was similar to “strangulate.” During their final months of training, the five men found themselves speaking the other’s language as often as possible.

For Deke Slayton it was the culmination of a 16-year wait to get into space, after having been grounded in March 1962, only weeks before his scheduled Mercury mission, by a suspected heart condition. Even though he was returned to flight status in early 1972, Slayton’s case remained under the medical microscope and NASA doctors insisted on a new ruling: If the astronaut developed any heart fibrillations during the countdown, the clock was to be held at T-4 minutes and he was to be removed from the Apollo 18 command module. Chris Kraft, director of the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, was furious at this idea. “He called me and asked me what this was all about,” wrote former flight surgeon Dr. Chuck Berry, “because he thought Deke was fully qualified to fly.”

Berry had left NASA in 1974 and went to JSC to assure the doctors that Slayton wasn’t going to fibrillate on the launch pad. The ruling was unnecessary, he argued, and even if anything untoward did happen, Slayton was a slow fibrillator and should not be adversely affected. When the astronaut returned from his long-awaited mission, he gave Berry a gift of thanks. It was the cardiac monitor from his medical harness, mounted onto a piece of tracing paper, on which was printed the reading of his heartbeat. It remained steady, with no fibrillations, throughout the nine-day mission. …

Early on 15 July 1975, Stafford, Brand, and Slayton were asleep in their quarters at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, when Soyuz 19 underwent its final preparations for launch at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, within today’s Kazakhstan. Chris Kraft and other senior managers were at their consoles in Houston, listening to voice telemetry from the Soviet Union. Compared to the excitement associated with the countdowns to U.S. launches, the final seconds of Soyuz 19’s time on Earth seemed anti-climatic:

“ … This is Soviet Mission Control Center. Moscow Time is 15 hours, 15 minutes. Everything is ready at the cosmodrome for the launch of the Soviet spacecraft, Soyuz. Five minutes remaining for launch. On-board systems are now under on-board control. The right control board … opposite the commander’s couch is now turned on. The cosmonauts have strapped themselves in and reported that they are ready. They have lowered their face plates. The key for launch has been inserted … ”

Five minutes later, the ethereal stillness of the barren steppe was broken by the retraction of the fueling tower from the rocket and a steadily increasing din as the R-7 rocket’s central core and its four strap-on boosters roared to life. Liftoff occurred at 3:20:10 p.m. Moscow Time (7:20:10 a.m. EDT and 6:20:10 a.m. CDT). Almost five years since its inception, the first part of ASTP was officially underway. The ascent to orbit was almost flawless, with the only problem being the failure of one of the on-board television cameras. “For a mission whose significance was to demonstrate to a watching world that co-operation in space is possible,” Leonov wrote in his autobiography, Two Sides of the Moon, “this was a problem that had to be solved quickly. We had no choice but to dismantle a major part of our orbital section in order to gain access to the wiring for the system of five cameras connected to the switchboard and fix the problem by disconnecting the switchboard from the circuit. It took us many hours, during which we had been scheduled to sleep.”

It was fortunate that Kubasov—renowned throughout the cosmonaut corps as something of a handyman—was aboard, although their efforts to bring the failed camera back to life were ultimately fruitless. This upset some of the Americans, in particular Bob Shafer, NASA’s deputy head of public affairs, who was concerned that there might now be no images of the Apollo spacecraft in orbit. For the cosmonauts, though, their efforts to fix the camera almost assured them a second career after landing. “On our return to Earth,” Leonov wrote, “this prompted a hilarious mail bag of requests from fellow Soviet citizens wanting Kubasov and me to come and fix their television sets!”

Fixing TVs was the last thing on the minds of most of the NASA flight controllers that morning. Despite all the reservations and the mistrust and the lack of transparency and openness in the early days, the Soviets had well and truly stepped up to the plate and launched precisely on time. Now it was America’s turn. In a coastal region of Florida, prone to electrical storms and severe weather phenomena, in mid-July 1975, there was a 23 percent chance of Mother Nature throwing a spanner in the works; and for this reason, Apollo 18 had no fewer than five launch windows, between 15-19 July, before it would be necessary to stand down the ground crews. Of course, if more than two of these chances were missed, the joint mission would be ruined: for Leonov and Kubasov would have to return to Earth and their backups, cosmonauts Anatoli Filipchenko and Nikolai Rukavishnikov, would have to be launched in their stead. At the very least, such an outcome would be hugely embarrassing for NASA.

The first order of business on the morning of 15 July was Chief Astronaut John Young tapping on the bedroom doors of Stafford, Brand, and Slayton, giving them the news that Leonov and Kubasov were in space and a long day lay ahead. Seeing Young reminded Slayton of the role that he had fulfilled for more than a decade as Co-ordinator of Astronaut Activities and later head of the Flight Crew Operations Directorate (FCOD): waking each crew up on launch morning, joining them for a “low-residue” breakfast of steak and eggs, helping them to don their space suits, engaging them in last-minute banter … then watching as they headed off on their missions and he stayed behind. The tables were now turned. “It was unusual,” he wrote, “for me to be on the other end of that little bit of business.”

Out at Pad 39B, propellant loading of Apollo 18’s Saturn IB booster was nearing completion—liquid oxygen and highly refined RP-1 kerosene for its S-IB first stage and liquid oxygen and hydrogen for the S-IVB second stage. Thunderstorms were in the vicinity, but were not expected to disrupt the launch, which was scheduled for mid-afternoon. ASTP’s U.S. manager, Glynn Lunney, spoke to his Soviet counterpart, Konstantin Bushuyev, by telephone, congratulating him on the successful launch of Soyuz 19 and advising that events were proceeding normally at NASA’s end. Shortly after noon, fully-suited, Stafford, Brand and Slayton left the Operations and Checkout Building, bound for the pad. In his autobiography, We Have Capture, Stafford wondered what thoughts were passing through Slayton’s head … and in his autobiography, Deke, all Slayton could describe was that it felt pretty good to be crossing the swing-arm to the spacecraft. “What the hell,” Slayton wrote, “it was only 13 years overdue. I never planned on being the world’s oldest rookie astronaut, but I wasn’t going to complain.”

As he waited to be inserted into the command module, Stafford took a final look at the skeletal framework of Pad 39B. He was keenly aware that this would be the last American manned launch for several years, and he wondered when the next piloted spacecraft would leave from this particular complex. Little could he possibly have known that it would be more than a decade before Pad 39B would again see service … and on that occasion, it would witness one of the greatest calamities of the space program so far: Challenger.

As rookie astronaut Bob Crippen helped Stafford connect his electrical, oxygen, and communications umbilicals on the left side of the command module, Slayton prepared to take his seat on the right side. Although his title of “Docking Module Pilot” implied that his sole responsibility was the docking module, Slayton’s primary tasks during ascent and re-entry were to monitor the ship’s electrical systems. Last to enter was Brand, the command module specialist, who took the centre seat. Checking in with test conductor Clarence “Skip” Chauvin and the blockhouse capcom, Karol “Bo” Bobko, Stafford asked if the countdown would be in English or Russian.

“Oh, I figured I’d give it in English!” responded Bobko, with a chuckle.

A little under eight minutes before launch, with all 556 switches, 40 event indicators, and 71 console lights checked and cross-checked, Stafford asked Bobko to tell the Soyuz crew to get ready for them. The launch itself, at precisely 3:50 p.m. EDT, was perfect, and Stafford found the ascent to be very gentle and smooth, like an elevator. As a veteran of two Gemini launches and a bone-rattling ride on the Saturn V, he was not expecting the rise from Earth to be quite so serene. Even the period of staging, as the S-IB first stage burned out and the single J-2 engine of the S-IVB second stage took over, seemed much calmer; it was “noticeable,” he wrote, but nowhere near as violent as the Saturn V.

Slayton, a man of few words, described the experience of his first launch into space as being louder than he had expected, but otherwise not surprising. His desire to sit back and enjoy his ride into orbit yielded to a sensation of balancing at the end of a long rubber balloon which was fighting its way through wild winds. “I love it!” he yelled as the Saturn’s first stage burned out and the S-IVB picked up the thrust for the final boost into orbit. “Man, I’ll tell ya … this is worth waiting 16 years for!” It had, after all, been 1959 when he was chosen by NASA for astronaut training.

“You liked that, huh?” grinned Stafford.

“I’d like to make that ride about once a day!”

Forty minutes after leaving Florida, and by now on the opposite side of the planet, Tom Stafford radioed Capcom Dick Truly in Houston to advise him that the crew were preparing to perform the “transposition and docking” maneuver to extract the docking module from the S-IVB. In a similar manner to the removal of the lunar module on earlier missions, the astronauts uncoupled Apollo from the S-IVB and the panels of the conical spacecraft adaptor were explosively jettisoned, exposing the docking module to the environment of low-Earth orbit for the first time. With Stafford at the controls, the first problem arose: all he could see was the blinding glare of the sunlit Pacific Ocean ahead of him. “I sat there, a few meters from the DM,” he wrote, “and began to sweat. Finally, I decided the only choice was to use the Mark I eyeball—lining up on the cross-shaped target mounted atop the truss behind the DM, and, once the DM had drifted toward a darker background, thrusting closer.”

Stafford achieved a perfect docking, aligning the two vehicles to an accuracy of better than one hundredth of a degree. It was the best accuracy ever achieved with the Apollo docking system. At the instant of capture, however, the crew were out of direct radio communications with the ground and had to wait some minutes before they could tell Truly that all was well. Shortly afterwards, during a five-minute communications pass over the tracking ship USNS Vanguard, the crew successfully extracted the docking module from the S-IVB.

Everything was now in place for Apollo to begin a complex series of maneuvers over the next two days to precisely match its orbit with that of Soyuz, undertaking the active role in the rendezvous. Shortly before bedding down for his first night’s sleep in orbit, Brand set to work disassembling the bulky docking probe from the connecting tunnel between the command and docking modules. It was his intention to open the docking module’s hatch and store an experimental freezer—needed for several joint experiments—there overnight. Very soon, however, he realised that he could not properly insert the tool to unlock and collapse the probe. Back home in Houston, Bo Bobko was the duty capcom.

“Okay, Bo,” radioed Brand. “Everything in the probe removal checklist on the cue card … has been going great [but] Step 12 is ‘capture latch release, tool 7.’ You insert it in the pyro[technic] cover [and] you turn it 180 degrees clockwise to release the capture latches. Well, here’s where the problem is and let me explain it to you. Do you have somebody there that knows the probe that can listen?”

Bobko quickly found a probe expert. “Roger,” he verified. “Go ahead.”

“Okay,” continued Brand, “as I look in the back of the … pyro cover, I’m looking with my flashlight through the hole where I insert this tool and there’s something behind the pyro cover that’s preventing me from putting this tool all the way in. It’s actually one of the pyro connectors. This tool has to go down through the pyro cover in between … some pyro connectors, but one of these pyro connectors has rotated such that it’s in the way … ”

Flight Director Neil Hutchinson would later tell reporters that Brand and Bobko spent around 18 minutes troubleshooting the problem with the probe, then decided to delay moving the freezer into the docking module until the following morning. When Brand then tried to close the hatch, he found that the partially-removed probe stopped him from doing so. It was already over an hour past the crew’s scheduled bedtime, so Mission Control recommended that they postpone further work. In the meantime, the astronauts slightly raised the command module’s cabin pressure to provide additional oxygen and thereby compensate for the nitrogen coolant which was boiling off the freezer.

Sleep proved more awkward than anticipated. The crew folded up Brand’s centre couch to gain additional space, with two men sleeping in the side couches and the third in a sleeping bag strung across the command module’s lower equipment bay, but even that did not work very well. From the second night, Slayton opted to curl into the narrow, cylindrical docking module (which he had earlier jokingly called “the world’s fastest, highest-flying sewer pipe”) and sleep there. Brand bedded down in the transfer tunnel and Stafford remained aboard the command module.

Next morning, they returned to the probe issue, completing each of the 11 steps from the previous night in order to re-engage it in its fully locked position. They then removed the pyro cover, straightened out the misaligned pyro cap, proceeded through the 11 disassembly steps, and finally inserted the key to unlock the capture latches. It was, Neil Hutchinson told journalists, more of an annoyance than anything else, and it warranted hardly a mention in Stafford’s and Slayton’s autobiographies: the former simply making reference to “a balky docking probe,” the latter to “some little problem with the hatch.” The real deal was the rendezvous.

Two burns of the service module’s Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine served firstly to circularize their orbit and later adopt an elliptical path to gradually close the gap with Soyuz.

Alexei Leonov and Valeri Kubasov were by no means inactive, despite their unsuccessful attempt to repair the television camera, and by the morning of 17 July the distance between Apollo and Soyuz was a little over 560 miles (900 km). Shortly after 8:00 a.m. CDT (5:00 p.m. in Moscow), Tom Stafford fired the SPS for a third time to lower his apogee in order to complete the next stage of the rendezvous. From his station, Vance Brand spotted the Russian craft as a bright speck in the darkness, and five minutes later Deke Slayton managed to contact the cosmonauts in Russian on VHF radio:

“Soyuz, Apollo. How do you read me?”

“Very well,” replied Kubasov in English. “Hello, everybody.”

“Hello, Valeri,” Slayton continued. “How are you? Good day, Valeri.”

“How are you? Good day,” came the response.

Pleasantries completed, it was time for business. Half an hour later, Kubasov switched on the range tone transfer assembly aboard Soyuz to establish accurate ranging data between the two spacecraft. By now, their separation distance had closed to just 140 miles (225 km). At 9:12 a.m. CDT, Stafford executed another maneuver with the SPS which enabled Apollo to effectively “overtake” and catch up with Soyuz. A short terminal phase burn a little over an hour later brought the American craft to within 22 miles (35 km) of its Soviet counterpart. Shortly thereafter, at 10:46 a.m., Capcom Dick Truly relayed two important messages to the crews: “Moscow is Go for docking; Houston is Go for docking. It’s up to you guys. Have fun!”

The two craft drew nearer and nearer. By now, Leonov and Kubasov had retreated into their descent module and closed the hatch to the orbital module; similarly, the Apollo crew had sealed the docking module and were in their couches within the command module. Half a mile of empty space lay between them. At Stafford’s call, Leonov rolled the Soyuz some 60 degrees to place it into the proper orientation for the final approach. In Houston, Mission Control was packed: Administrator Jim Fletcher and his wife were there, along with Soviet Ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin and chief astronaut John Young, together other senior managers and a gaggle of astronauts, both veterans and rookies: Dave Scott, Joe Allen, Owen Garriott, Bruce McCandless, Story Musgrave, and Rusty Schweickart.

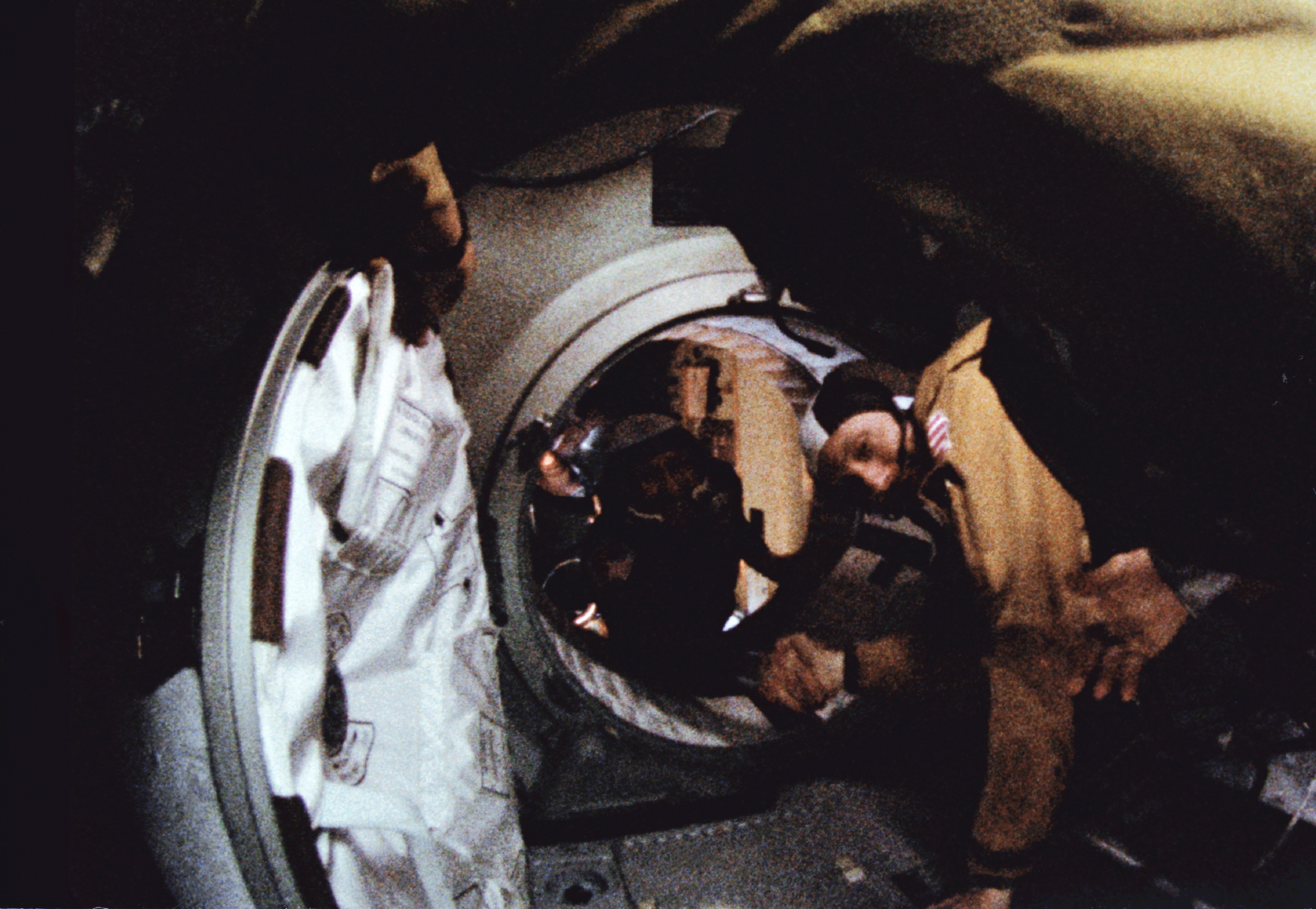

Apollo and Soyuz were coming up on the coast of Portugal as Stafford called out the closing distance, until, finally, at 11:09 a.m., the two craft met in a metallic embrace and he called: “Contact!”

A second or two later, Leonov rendered his own acknowledgement: “Capture! Soyuz and Apollo are shaking hands now!”

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Wasn’t the Command Module just called “Apollo” and not “Apollo 18”? I’m pretty sure it was never referred to as such officially.

ASTP was a significant event in manned spaceflight, paving the way for a truly international environment we casually take for granted. A couple of “linguistic” notes – Stafford’s Russian had a decidedly Oklahoma twang and Leonov’s remark to Stafford upon docking was, “It was a good show!” – with an obvious Russian accent. True pioneers, all five!

Great article, and very timely. I took my family yesterday, July 5th, to see the space shuttle Endeavor in its new home at the California ScienCenter in Exhibition Park in Los Angeles. While we waited for our turn to visit the shuttle complex, we deeply enjoyed viewing the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo capsules on display near the Endeavor exhibit entrance.

The Apollo capsule currently on display is on loan from the Smithsonian…it is the original Apollo ASTP capsule covered in your story. It was originally due to be designated as Apollo 18 when it was scheduled to fly to the moon, but after NASA budget cuts was repurposed for this historic first US/Russian joint mission in space. Thanks for providing these additionjal details on this great story!

“It was originally due to be designated as Apollo 18 when it was scheduled to fly to the moon, but after NASA budget cuts was repurposed for this historic first US/Russian joint mission in space.”

Actually, it was going to be flown on Apollo 15 back when it was originally an H-class mission. I believe the CSM that was originally intended for Apollo 18 wound up flying on 17 after the last few missions were cancelled.