As a cadre of 18 astronauts—nine men and nine women—are assigned to the “Artemis Team”, with a potential that they will be the next humans to set foot on the Moon, we are reminded today (14 December) of the very last time that men called the lunar surface their home away from home. On this day in 1972, Apollo 17 Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Jack Schmitt awoke for their final “morning” on the Moon.

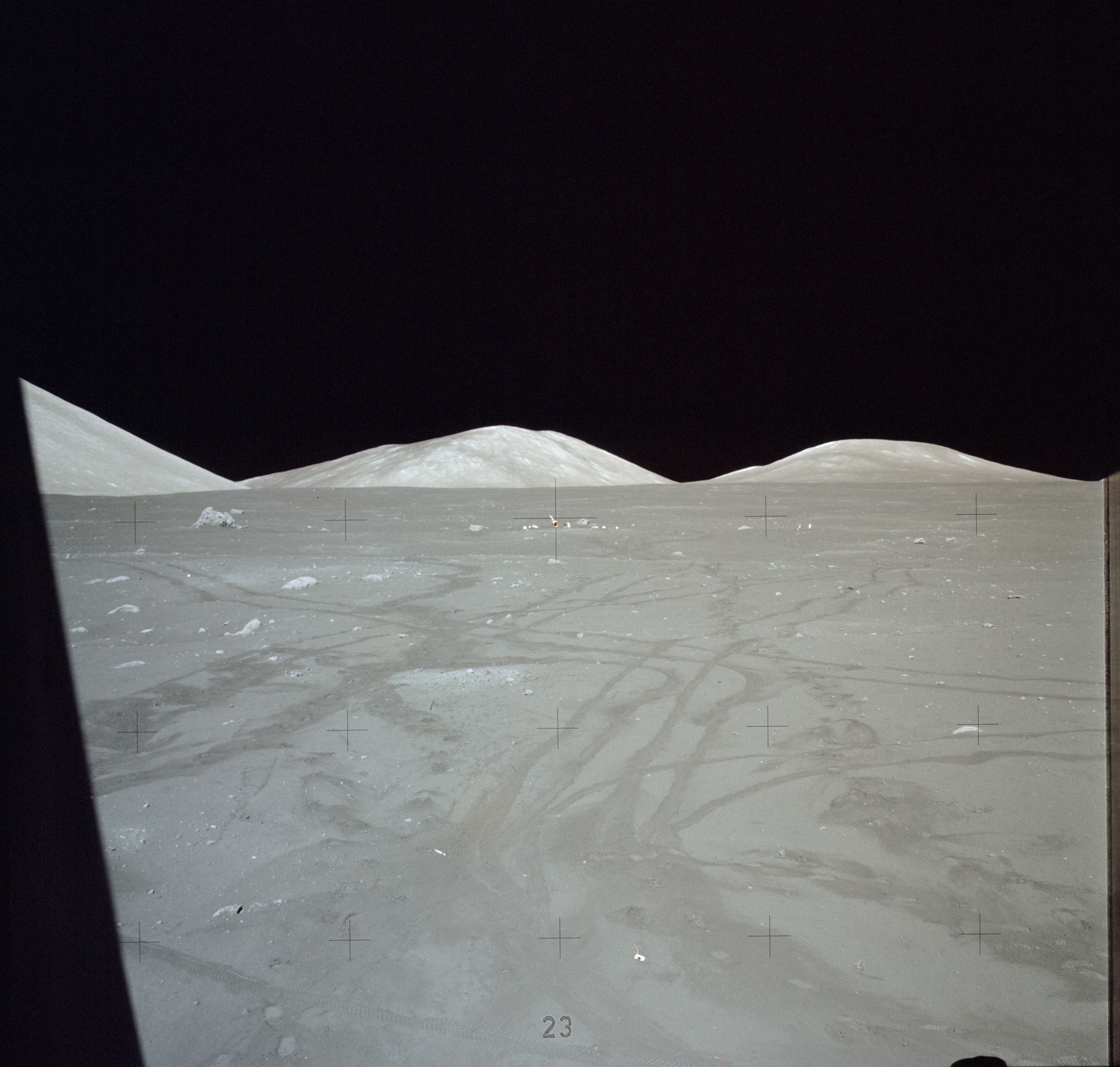

Launched a week earlier, they had spent three days in a pretty little valley called Taurus-Littrow, logged 22 hours walking its rugged terrain and driven 18 miles (29 km) in the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV).

But on 14 December 1972, Cernan and Schmitt awoke in the Lunar Module (LM) “Challenger” to the realization that this day would mark their departure from the Moon and their return to Earth, though neither man could have imagined that it would be more than a half-century before the next generation of lunar explorers would arrive.

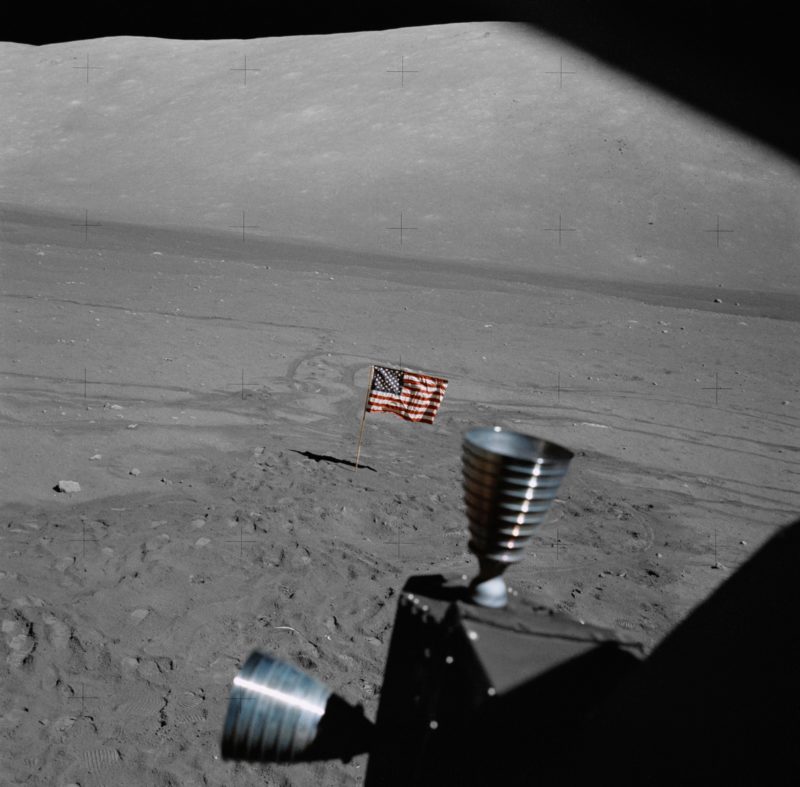

Late the previous “evening”, Cernan had taken humanity’s poignant last steps of the 20th century. He drove the battery-powered LRV to a spot about a mile from Challenger, parked it and configured its television camera to record their liftoff from the Moon. As he dismounted, for a moment he carved his daughter Tracy’s initials into the soft lunar topsoil. Then Cernan returned to Challenger and clasped the ladder for one final time.

“Bob,” he had radioed Capcom Bob Parker in Mission Control, “this is Gene and I’m on the surface. And as I take these last steps from the surface, back home for some time to come, but we believe not too long into the future, I believe history will record that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow…And as we leave the Moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came, and God willing as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.”

Forty-eight years on, with Cernan and fellow Apollo 17 crewmate Ron Evans and having sadly left us, only eight of the 21 lunar voyagers are still with us and we can only hope that they will still be around when the Artemis Team makes its triumphant return to the Moon. The world bade farewell Neil Armstrong way back in 2012, and most recently Apollo 15 Command Module Pilot (CMP) Al Worden was lost to us in March.

Many of those pioneers expressed their undisguised angst over the years that the glory of Project Apollo had been unceremoniously abandoned in its prime. Quoted by Andrew Chaikin in his landmark book A Man on the Moon, Apollo 14 astronaut Stu Roosa once remarked that “history will not be kind to us, because we were stupid”.

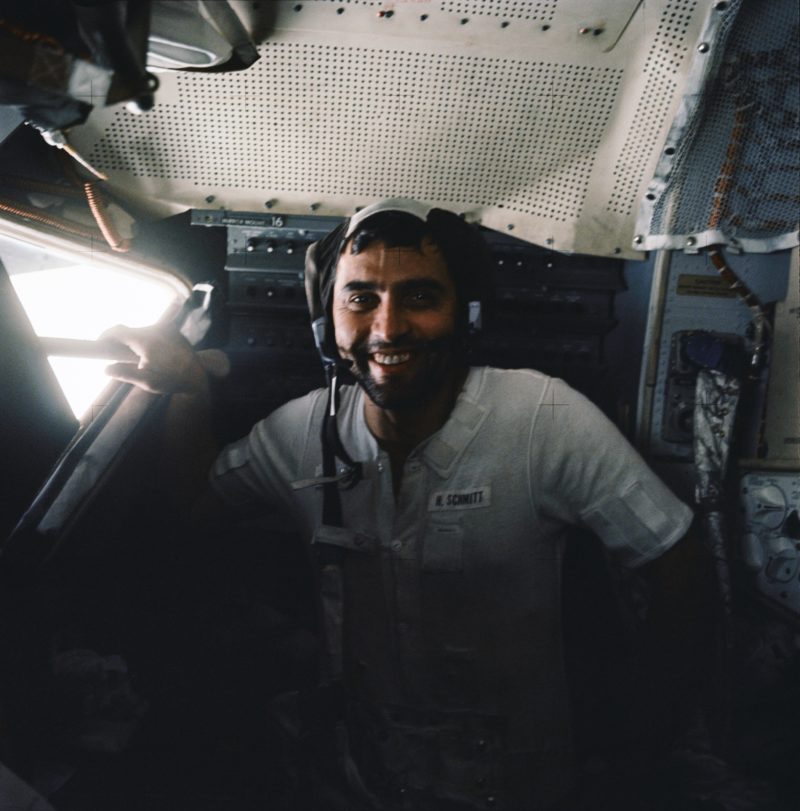

Cernan and Schmitt received their customary wake-up call on 14 December 1972 in the broom-cupboard-sized confines of Challenger’s tiny cabin by Capcom Gordon Fullerton. But in actuality, both men were already awake, following a sleepless final night in the ethereal stillness of the Moon. Schmitt had enjoyed about six hours of fitful sleep, Cernan about five. “We’re in the midst of a nice hamburger omelet,” Cernan chuckled, to which Schmitt added that most of their breakfast had ended up all over them.

It was a little more than a week prior to Christmas, so Schmitt sang Fullerton a tune:

It’s the week before Christmas

And all through the LM

Not a commander was stirring

Not even Cernan.

The samples were stowed in their places with care,

In hopes that, with you, they soon will be there.

And Gene is his hammock and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a short lunar nap.

Asked by Fullerton if he had spent all night composing his masterpiece, Schmitt replied: “Gordy, that’s for the kids. They are the future.” Little could Schmitt have possibly known that only three potential future lunar explorers—Joe Acaba, Scott Tingle and Stephanie Wilson—were alive at that very moment, with Kjell Lindgren born a month after Apollo 17’s return to Earth.

Those final hours on the Moon were a flurry of activity, as Challenger’s hatch was opened one final time to discard unneeded equipment. “Cameras, tools, backpacks and other now-useless material were flung to the surface,” Cernan wrote in his memoir The Last Man on the Moon. “We had to shed weight if we were going to get off the Moon safely.

Mission planners had worked out the exact balance needed and every container of rocks we brought aboard was weighed on a hand-held fish-scale, calibrated for one-sixth gravity, before being stored. We had just enough fuel to get us into orbit with almost no margin for error, so the overall weight of the spacecraft, its passengers and cargo of rocks was critical. We threw out nearly everything that wasn’t nailed down.”

Although Cernan and Schmitt liked to refer to this short session as an Extravehicular Activity (EVA) in its own right—and although Challenger’s cabin pressure was reduced to a condition of near-vacuum—they would not physically leave the LM again. Instead, they bagged up the “jettison bags” just inside the hatchway and gave them each a hefty kick to deliver them just over the lip of Challenger’s tiny porch.

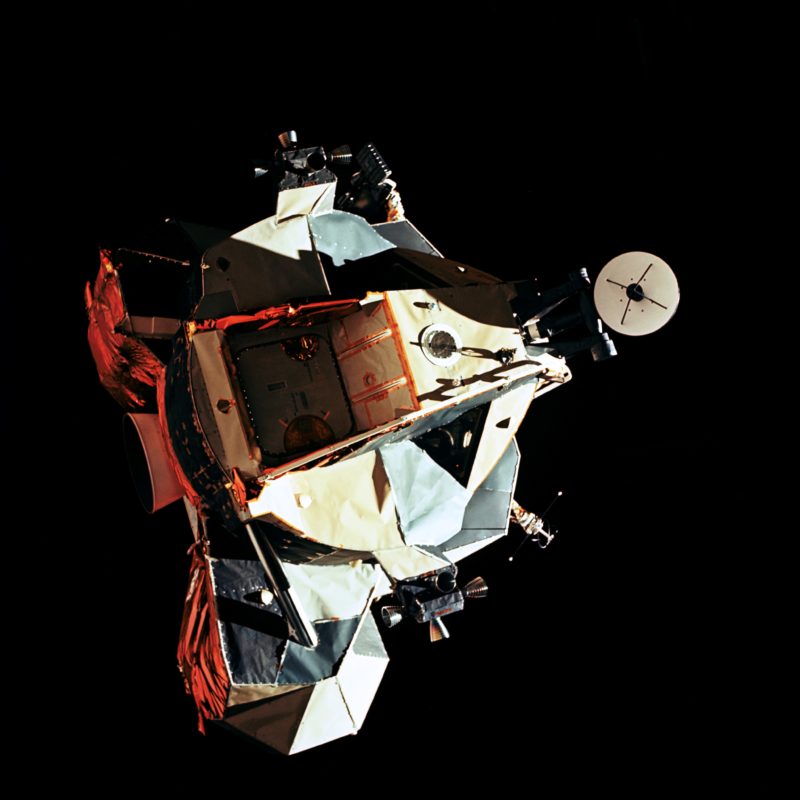

From there, they would fall like snowflakes in the low lunar gravity to the surface. Schmitt snickered and called them “Santa Claus bags”. A brief communications “pass” with crewmate Ron Evans in the orbiting Command and Service Module (CSM) “America” prompted Cernan to remind him to keep the docking probe extended and ready for their arrival. Evans promised that he would.

Finally, with everything buttoned up and ready to leave, the last human explorers of the Moon bade farewell to Taurus-Littrow at 188 hours and one minute into the Apollo 17 mission. “Let’s get this mother outta here,” Cernan radioed, in what would prove to be some of the final words—to date—to be spoken by humans on another celestial body. Within a matter of minutes, Challenger’s ascent stage had achieved a low lunar orbit and soon thereafter made a perfect docking with a very happy Evans. Several days later, on 19 December, America splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, closing out the first chapter of humanity’s exploration of the Moon.

And as the Artemis Team looks set, hopefully, to return there in a few short years’ time, we cannot fail to be reminded of Gene Cernan’s last words on the surface:

God willing…

We shall return…

Someday!

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » Apollo »

As each year passes, the Apollo missions become more incredible. Let’s hope the Artemis missions continue the legacy of “exploration at its finest.”

Looking at the surface photos of the Apollo 17 mission, it illustrates how “smooth” the mountains and hills in the distance are compared to those in the old sci-fi movies. Those scenes showed very sharp features of the lunar landscape, not at all like the reality we see.