After more than 25 days in space and 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) traveled, NASA’s Artemis I mission came to a triumphant conclusion at 9:40 a.m. PST Sunday, when the Orion Crew Module (CM) splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, to the west of Baja California. Descending beneath three perfect red-and-white parachutes, the spacecraft’s near-month-long voyage saw it venture further from Earth—some 270,000 miles (435,000 kilometers)—than any vehicle capable of carrying humans and clear a significant hurdle on the road to Artemis II, the long-awaited return of astronauts to the vicinity of Moon, currently targeted for 2024.

“The splashdown of the Orion spacecraft, which occurred 50 years to the day of the Apollo 17 Moon landing, is the crowning achievement of Artemis I,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “From the launch of the world’s most powerful rocket to the exceptional journey around the Moon and back to Earth, this flight test is a major step forward in the Artemis Generation of lunar exploration.

“For years, thousands of individuals have poured themselves into this mission, which is inspiring the world to work together to reach untouched cosmic shores,” Mr. Nelson continued. “Today is a huge win for NASA, the United States, our international partners and all of humanity.”

“With Orion safely returned to Earth, we can begin to see our next mission on the horizon, which will fly crew to the Moon for the first time as a part of the next era of exploration,” said NASA Associate Administrator for the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, Jim Free. “This begins our path to a regular cadence of missions and a sustained human presence at the Moon for scientific discovery and to prepare for human missions to Mars.”

Launched at 1:47:44 a.m. EST on 16 November from historic Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida—a complex unused for a launch since the Ares I-X test flight back in October 2009—Artemis I marked the initial voyage of the 322-foot-tall (98-meter) Space Launch System (SLS), which has now decisively surpassed the Saturn V as the most powerful rocket ever successfully launched into space. Pummeling the soles of feet, pounding the chests of spectators and even blowing away Pad 39B’s elevator doors with 8.8 million pounds (3.9 million kilograms) of thrust, the four shuttle-heritage RS-25 engines on the Core Stage and a pair of five-segment Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) powered the first SLS airborne on a spectacular maiden outing.

The boosters were jettisoned as planned, two minutes into ascent, leaving the Core Stage alone to continue the push to low-Earth orbit, when its RS-25 suite shut down on time a little past eight minutes after liftoff. This left the 45-foot-tall (13.7-meter) Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (iCPS) to execute a pair of critical “burns”, firstly to raise the low point (or “perigee”) of Orion’s orbit to enter a circular path around Earth, and secondly to depart the Home Planet’s gravitational well for a multi-day transit to the Moon.

Those burns—a short, 20-second Perigee Raise Maneuver (PRM), then the 18-minute Translunar Injection (TLI)—were satisfactorily performed by the iCPS’ RL-10C engine. After this was complete, the Orion Crew Module (CM) and attached European Service Module (ESM) separated and entered free flight almost two hours after launch.

By this time, the spacecraft’s four solar arrays had been deployed, with Orion Vehicle Integration Manager Jim Geffre noting that they generated more electrical power than anticipated and better-than-expected heat-rejection.

Eight hours into the flight, Orion’s shuttle-heritage Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engine was fired for the first outbound trajectory correction burn, with a second performed by the ESM’s auxiliary thrusters early on 17 November.

Despite 13 performance “funnies” experienced during launch (including an issue with Orion’s star trackers, which appeared to have been inadvertently dazzled by thruster-plume behavior), the spacecraft performed admirably as it headed into deep space.

At 2:09 p.m. EST on 20 November, Orion entered the lunar sphere of gravitational influence, where the Moon surpassed Earth in exerting the principal gravitational tug on the spacecraft. Another pair of outbound trajectory correction burns fine-tuned the flight profile.

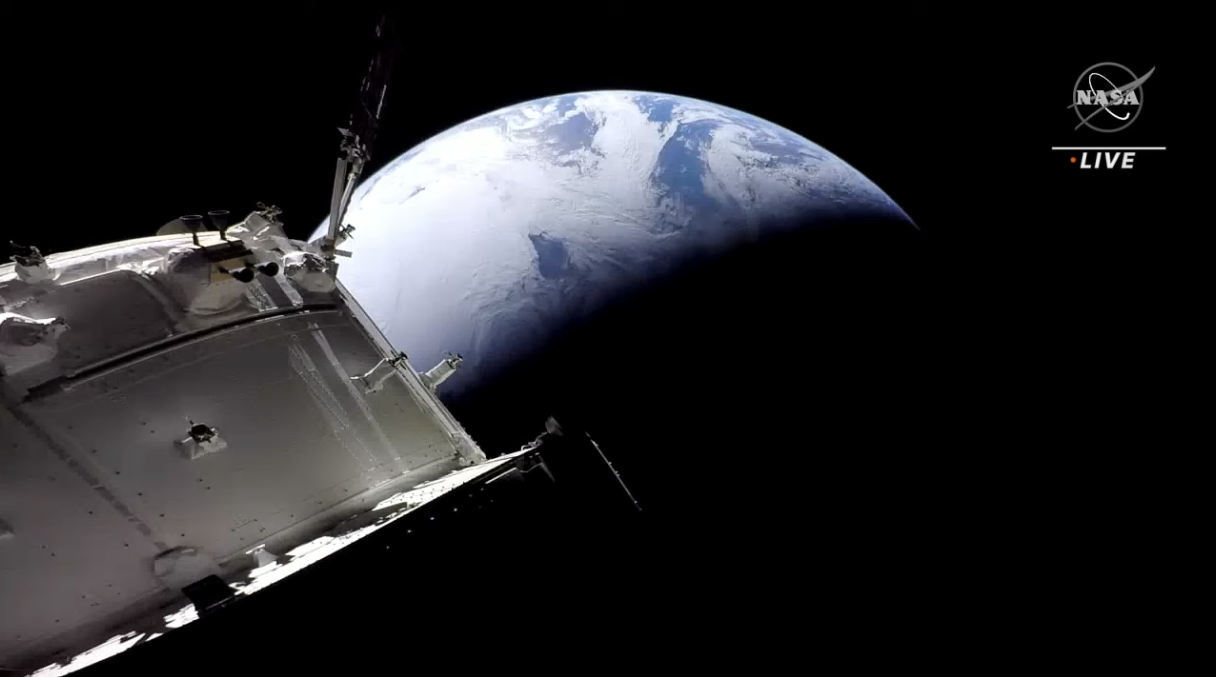

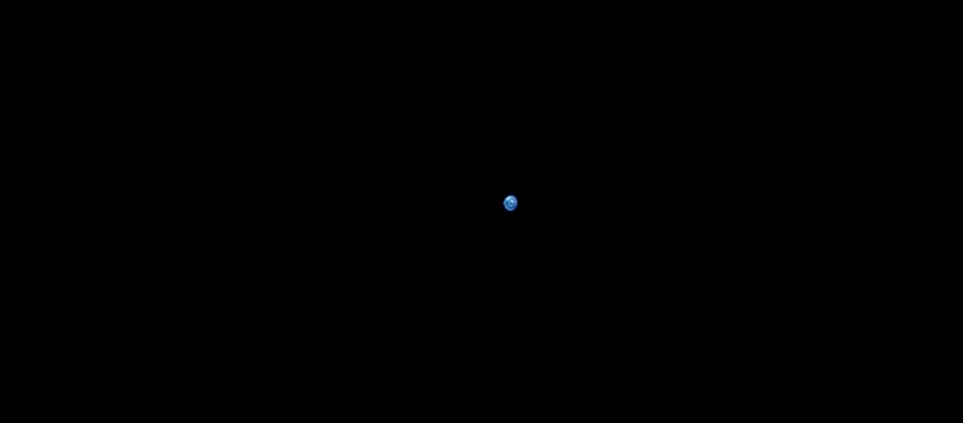

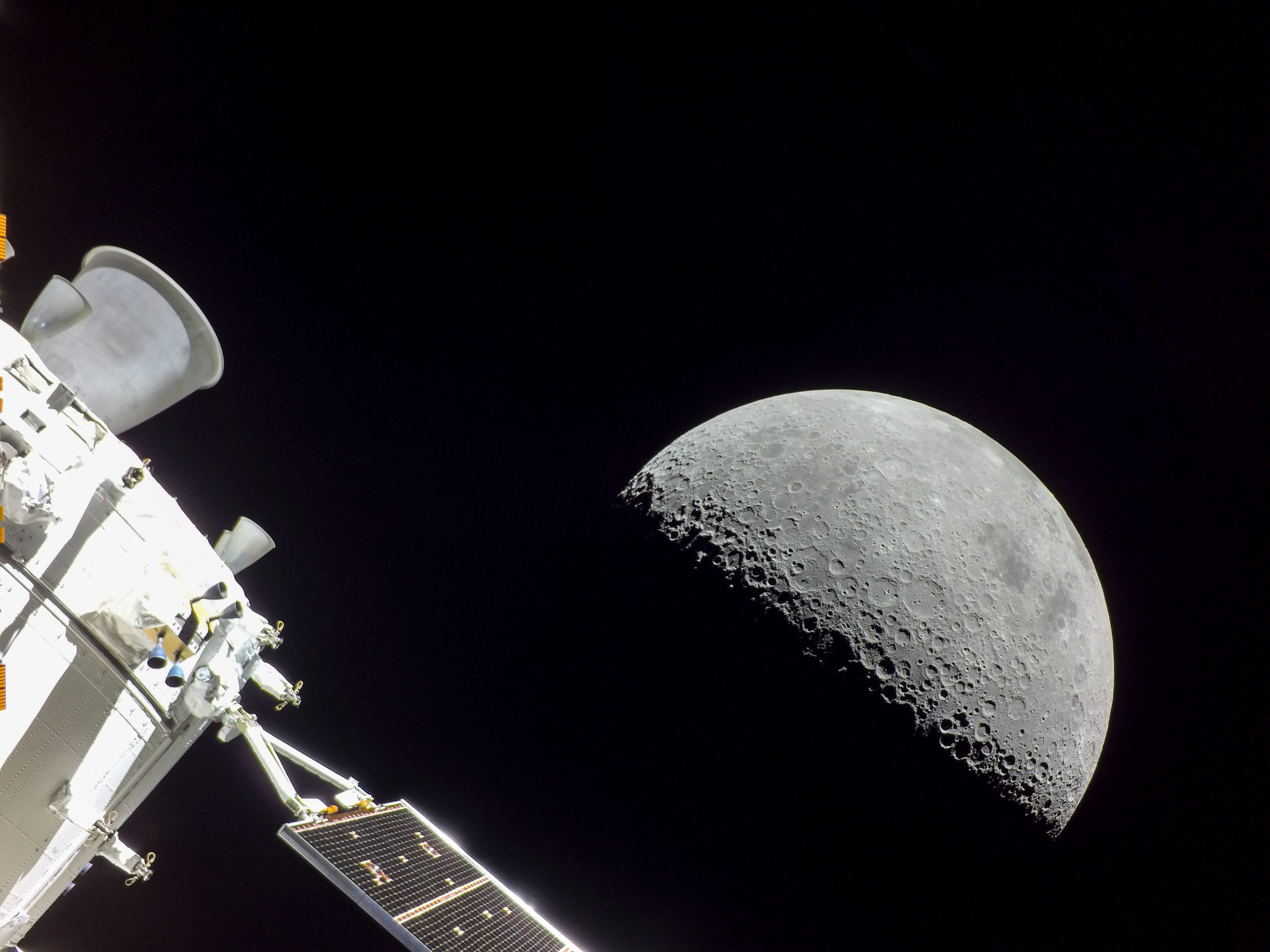

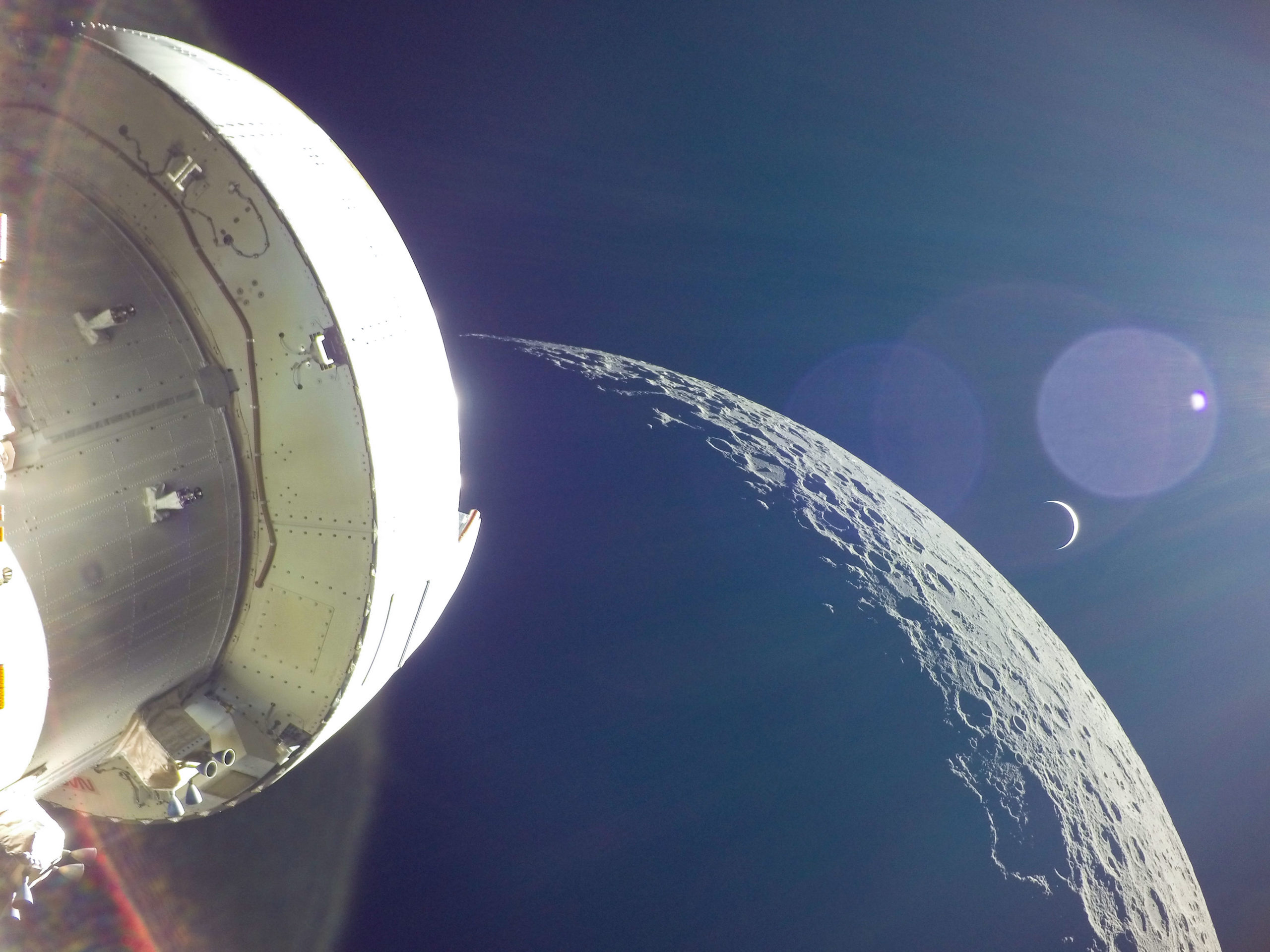

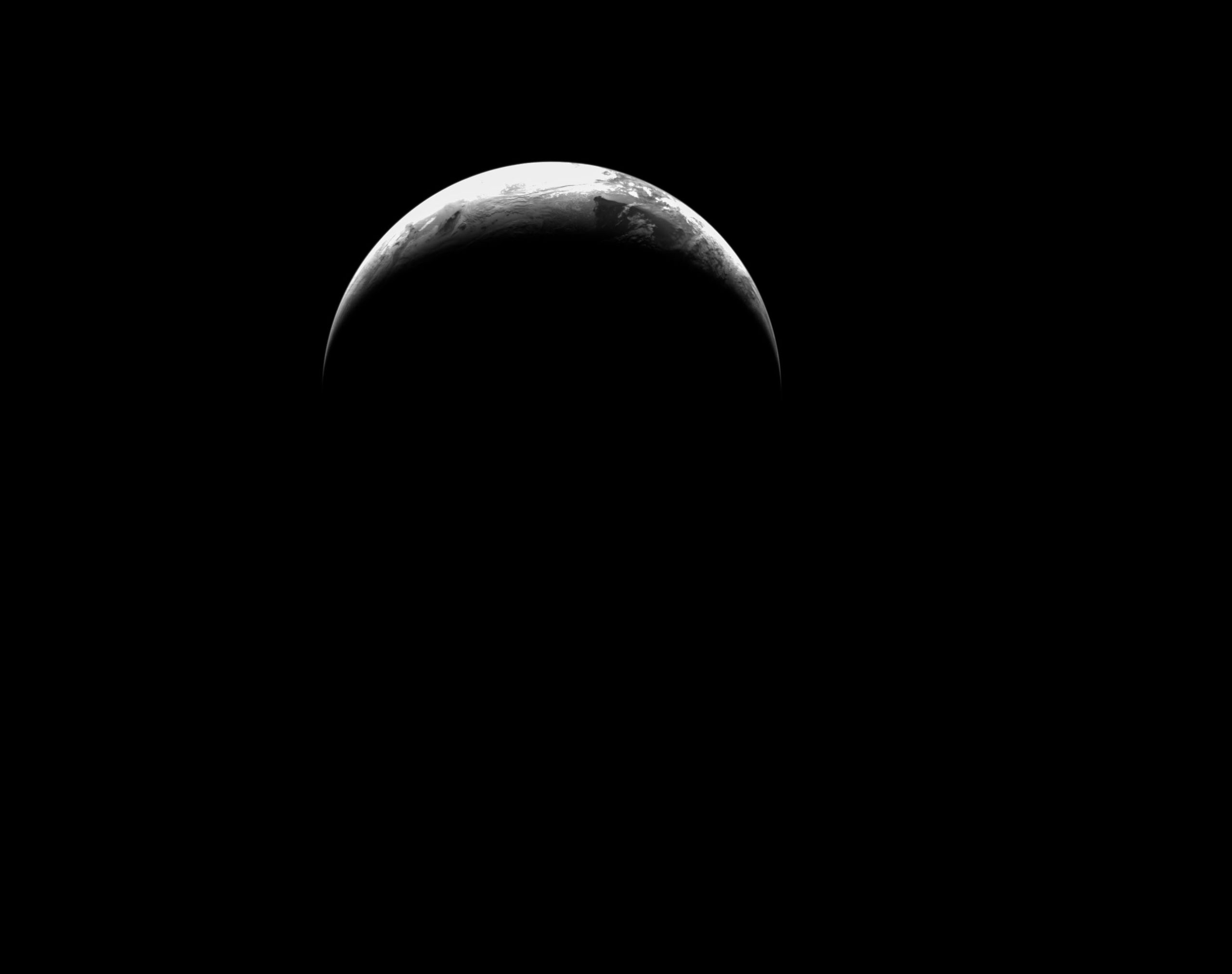

On 21 November, the OMS executed the first of four major burns of the Artemis I mission: the critical Outbound Powered Flyby, lasting 150 seconds, which brought Orion to within 81 miles (130 kilometers) of the Moon at 7:57 a.m. EST. Stunning imagery returned from cameras mounted at the tips of the spacecraft’s solar arrays revealed the breathtaking majesty of the Home Planet, a tiny blue-and-white marble, 229,000 miles (368,500 kilometers) away, surrounded by a sea of darkness.

It evoked memories of Carl Sagan’s description of Earth as seen by Voyager 1: a “pale blue dot”. Not long after the Outbound Powered Flyby, the spacecraft swept over three Apollo landing sites, passing 1,400 miles (2,250 kilometers) over the Sea of Tranquility (Apollo 11), 6,000 miles (9,650 kilometers) over the Fra Mauro Formation (Apollo 14) and 7,700 miles (12,400 kilometers) over the Ocean of Storms (Apollo 12).

Four days later, at 5:52 p.m. EST on 25 November, the OMS engine performed its second major burn, lasting 88 seconds, to insert Orion into Distant Retrograde Orbit (DRO). This set the stage for six full days in the DRO orbit, which carried the spacecraft as “distant” from the Moon as 40,000 miles (64,000 kilometers).

And that distance, not only from the Moon, but also from the Home Planet, allowed a new record to be snared early on 26 November: the farthest distance ever traveled by a spacecraft designed to carry humans. At 8:42 a.m. EST, Orion surpassed Apollo 13, which during its ill-fated flight in April 1970 reached a maximum distance from Earth of 248,655 miles (400,171 kilometers).

And just after 4 p.m. EST on 28 November, the spacecraft reached its greatest distance from home, some 268,563 miles (432,210 kilometers). Finally, at 4:53 p.m. EST on 1 December, the return journey back to Earth got underway, when the OMS engine ignited for a 105-second burn to depart the DRO.

Re-entering the lunar sphere of influence late on the 3rd, Orion performed its second close approach to the Moon on the morning of the 5th, returning astonishing views from just 80.6 miles (129.7 kilometers). A little while later, the OMS came alive again for 207 seconds for the Return Powered Flyby burn to depart lunar orbit for good and set course for home.

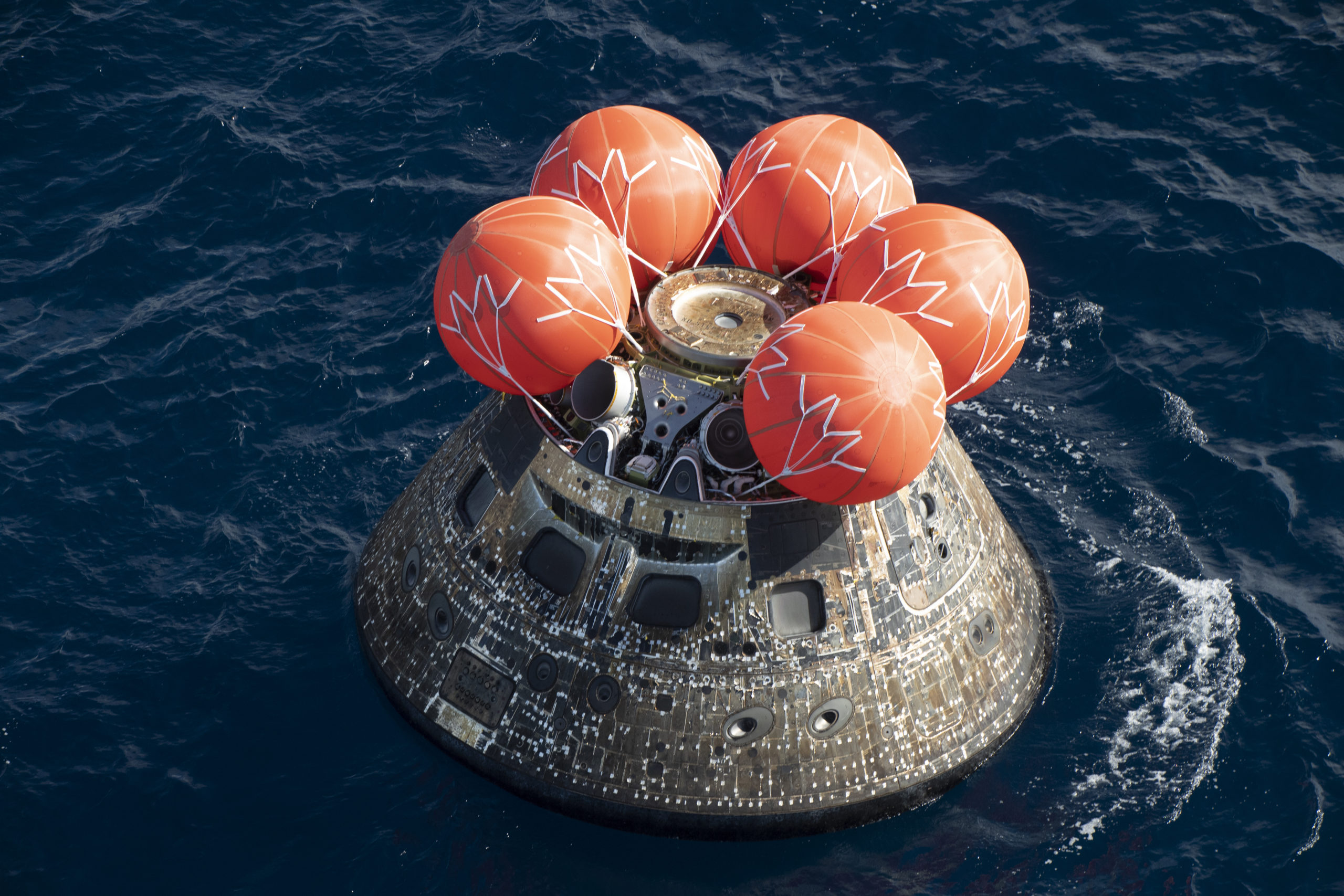

And as Earth grew steadily larger in Orion’s windows, plans for the parachute-assisted splashdown on Sunday 11 December were fine-tuned to a landing point off the Baja Coast in the Pacific Ocean, near Guadalupe Island, just south of the primary recovery zone. After splashdown, the spacecraft would be recovered by NASA and Department of Defense personnel aboard the amphibious dock ship USS Portland.

Heading back home, the ESM, its 25.5-day job done with flying colors, was separated from the Orion CM at 9 a.m. PST (12 p.m. EST) Sunday. Alone now, the CM performed a unique “skip-entry” technique, dipping briefly into the upper atmosphere to utilize its drag effects and the lift characteristics of the capsule to achieve a safe, parachute-aided splashdown at 9:40 a.m. PST (12:40 p.m. EST), wrapping up Artemis I with a mission elapsed time of 25 days, ten hours and 52 minutes.

In addition to the remarkable achievement of flying a human-capable spacecraft to and from the Moon for the first time in five decades, Artemis I successfully trialed many of Orion’s systems in the unforgiving environment of deep space at levels far beyond those expected for astronauts. Notably, data from the Hybrid Electronic Radiation Assessor (HERA) is expected to yield valuable insights into the radiation environment at various stages of the mission’s journey.

All told, the mission proceeded from start to finish with very few wrinkles. A loss of data contact to and from the spacecraft on 23 November, lasting 47 minutes, was resolved through a ground-side hardware reconfiguration. And an issue last weekend with a Power Conditioning Distribution Unit (PCDU) posited no interruption of power to any critical systems.

Over the coming weeks and months, the data from Artemis I will be pored over as the first tentative steps begin to launch an as-yet-unannounced crew of four—including a representative of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the first non-U.S. professional astronaut ever to leave Earth orbit—on Artemis II in the 2024 timeframe. NASA’s Reid Wiseman, who last month stepped down as chief of the Astronaut Office, handing his duties in an acting capacity to fellow astronaut Drew Feustel, announced recently that a crew assignment is anticipated before year’s end.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » SLS »

A great victory!