A once-used Falcon 9 booster successfully launched Europe’s Euclid telescope early Saturday, kicking off an ambitious six-year mission to measure the outward acceleration of the Universe and generate a better understanding of dark energy and dark matter. The 4,700-pound (2,100-kilogram) observatory—named in honor of the ancient Greek mathematician and “father of geometry”, Euclid of Alexandria—took flight from storied Space Launch Complex (SLC)-40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., at 11:12 a.m. EDT, aboard the same Falcon 9 that lifted Ax-2’s Peggy Whitson, John Shoffner, Ali Al-Qarni and Rayyanah Barnawi for their nine-day research expedition to the International Space Station (ISS) in late May.

Weather conditions for Euclid’s launch were highly favorable, with 90-percent acceptability on Saturday, falling slightly to 80 percent for Sunday’s backup opportunity, thanks to an anticipated increase in atmospheric moisture in the area. “Hot and humid conditions will persist across the area into the weekend,” noted the 45th Weather Squadron at Patrick Space Force Base in its L-1 update, issued Friday.

“With a mid-level ridge in the area, warm temperatures and low moisture in those levels will limit destabilization for showers and thunderstorms on Saturday,” it added. “We will still see cumulus cloud formation from late morning into the afternoon, so the primary concern will be the Cumulus Cloud Rule.”

Last week, the Autonomous Spaceport Drone Ship (ASDS), “A Shortfall of Gravitas”, put to sea out of Port Canaveral, bound for a position in the Atlantic Ocean to recover the Falcon 9 core after launch. It would mark the 35th drone ship “catch” of 2023 and—unlucky for some, perhaps, but certainly not today—the 13th of the year for ASOG.

Flying today’s mission was B1080, one of only three brand-new “single-stick” Falcon 9 cores to enter service in 2023. She was rolled out from the Horizontal Integration Facility (HIF) to the pad surface and elevated vertical yesterday.

B1080 first launched from historic Pad 39A at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) on 21 May to lift U.S. astronauts Peggy Whitson and John Shoffner and Saudi Arabia’s Ali Al-Qarni and Rayyanah Barnawi, to the ISS aboard Dragon Freedom for the Ax-2 mission on behalf of Houston, Texas-based AxiomSpace, Inc. Ax-2 made history by flying the first Saudi woman into space and the first time a female astronaut had commanded a commercial space mission.

Liftoff occurred on time at 11:12 a.m. EDT and B1080 powered smoothly uphill, her nine Merlin 1D+ engines delivering 1.5 million pounds (680,000 kilograms) of thrust for the opening 2.5 minutes of ascent. The core then separated from the stack and pirouetted to a pinpoint landing on ASOG’s deck, to wrap up the 42nd Falcon 9 launch of the year and SpaceX’s first flight of a busy July.

Alone now, the Falcon 9’s second stage picked up the baton to deliver Euclid on the first leg its month-long trek to the L2 Lagrange Point, situated about a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth, from where it will conduct its six-year mission. The Merlin 1D+ Vacuum engine executed a pair of “burns”—a first lasting six minutes, the second a little shy of a minute, later in ascent—to pre-position Euclid for deployment about 41 minutes after launch.

Developed more than a decade ago as a Medium-Class (“M-Class”) mission by the European Space Agency (ESA), Euclid was originally scheduled to fly a Russian Soyuz rocket out of the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana, but this launch provider was dropped following last year’s invasion of Ukraine. Last October, ESA announced that a SpaceX Falcon 9 had been selected instead to launch Euclid.

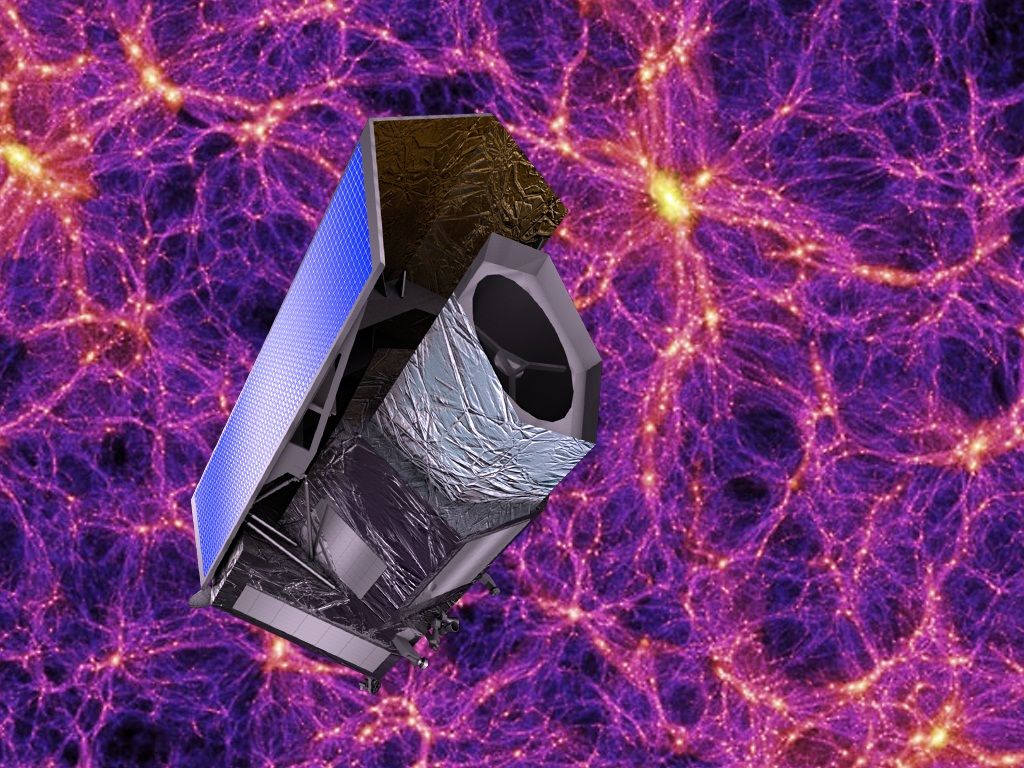

Euclid was selected as one of two Medium-Class missions—alongside Solar Orbiter—by ESA in late 2011 and received approval to move into full construction the following year. The spacecraft will probe the expansion of the Universe and the formation of cosmic structures by examining galactic redshift to an equivalent of ten billion years into the past.

Euclid is a Korsch-type telescope with a primary mirror some four feet (1.2 meters) in diameter and a pair of scientific instruments provided by the “Euclid Consortium”. This international group of some 2,000 scientists from 13 European nations, Canada and the United States, seeks to map up to two billion galaxies spread across 35 percent of the whole sky.

The Visible Light Camera (VIS) will allow for the measurement of the deformation of galaxies and the Near-Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP) carries sensitivity to near-infrared radiation and will measure redshifts—and thus distances—of galaxies with a precision ten times finer than previously possible. NASA joined the mission in January 2013, providing a suite of 20 detectors for NISP.

Euclid was built by Thales Alenia Space at its facilities in Cannes, France, with Airbus Defence & Space developing its payload module. The mission passed its Preliminary Design Review (PDR) in December 2015, with more than a hundred firms from 18 European nations selected to build components for the spacecraft.

Hardware began to arrive in February 2017, with the first delivered components consisting of four charge-coupled devices for the VIS instrument, followed by the completion of NISP’s infrared detectors later that same spring. The primary mirror for Euclid arrived in November 2018 and by year’s end the mission entered its Critical Design Review (CDR) phase, ahead of full structural assembly.

As this hardware and instrumentation came together, so too did the plans for Euclid’s ambitious mission. In mid-2019, the Euclid Consortium selected three “extremely dark” patches of sky for the Euclid Deep Fields—one in the northern sky, in the constellation of Draco the dragon, and two in the southern sky, in the constellations of Fornax the furnace and Horologium the pendulum clock—which will see the spacecraft cover a total of 40 square degrees of sky, equivalent to 200 times the “footprint” of the full Moon in the sky.

Originally targeting launch as early as 2019, Euclid slipped firstly into 2020 and was scheduled to fly in 2022 by the time that Thales delivered the spacecraft’s communications module in July 2019. Assembly of the Airbus’ payload module wrapped up later that year and in July 2020 the VIS and NISP instruments had completed their own testing and were integrated into Euclid the following December.

By now aiming for launch in late 2022 or early 2023, Euclid found itself at the center of international politics in February of last year, when Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine. Under to-and-fro sanctions imposed on the Russian regime by Europe, and on Europe by Russia, Euclid’s planned Soyuz ride to space was withdrawn and in October 2022 SpaceX’s Falcon 9 was selected in its stead.

Testing of the spacecraft thus continued against the backdrop of this evolving war in Eastern Europe. Last fall, Euclid concluded thermal, vacuum, acoustic and vibration testing and in April 2023 was shipped aboard the ESA vessel MN Colibri from the port of Savona in Italy to Port Canaveral, arriving at its launch site on the last day of the month.

Two weeks ago, it was fueled with 310 pounds (140 kilograms) of hydrazine and 155 pounds (70 kilograms) of gaseous nitrogen. These propellants will furnish chemical propulsion for its delivery to the L2 Lagrange Point and facilitate Euclid’s very precise and stable pointing towards its celestial targets.

With its first mission of July thus complete, SpaceX wraps up its 42nd Falcon 9 launch of the year and the 44th flight by a member of the Falcon family, inclusive of two Falcon Heavies earlier in 2023. So far, the Hawthorne, Calif.-headquartered organization has attained a flight rate across the fleet of one launch every 4.2 days, a substantial uptick over last year’s personal-best-beating achievement of 5.9 days.

Between March and June, SpaceX flew at least seven missions per consecutive month. Half of all of its flights so far in 2023 have been devoted to expanding the Starlink network of low-orbiting internet satellites, with others deploying eight large commercial geostationary communications satellites, three multi-payload Transporter “rideshares” and four crewed and uncrewed missions to the ISS.

Although SpaceX reveals precious little in terms of a flight manifest, July looks set to approach—or possibly exceed—seven launches, with as many as four more Starlink missions expected this month. Added to that list is the 20,000-pound (9,200-kilogram) Jupiter-3 communications satellite, riding a Falcon Heavy for the EchoStar Corp., and potentially the second launch of the Tranche-0 Transport and Tracking Layer (TTL) constellation for the Space Development Agency (SDA).

That carries the potential that July might close on 50 cumulative Falcon 9 launches so far in 2023. Putting that into context, only last year did SpaceX achieve more than 50 flights across an entire calendar year. And even 2022’s record-setting 61-mission year took until the first week of November to hit its 50th launch.

ESA and SpaceX:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=8vY-4zWKsJM