Ten years ago, today, Space Shuttle Discovery streaked back through the atmosphere and alighted on Runway 22 at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., concluding the first Return to Flight (RTF) mission in the aftermath of the Columbia disaster. After almost 30 months of introspection, self-criticism, repairs, and modifications—and, as described in yesterday’s AmericaSpace article, repeated rollouts and rollbacks from Pad 39B—the mission of STS-114 to resume construction and maintenance of the International Space Station (ISS) was finally underway. Aboard Discovery were Commander Eileen Collins, Pilot Jim “Vegas” Kelly, and Mission Specialists Soichi Noguchi of Japan and NASA astronauts Steve Robinson, Wendy Lawrence, Andy Thomas, and Charlie Camarda. However, despite successfully returning the shuttle fleet to space, their mission uncovered worrying signs that the issues which doomed Columbia had not been fully overcome.

Early on 26 July 2005, with liftoff of STS-114 targeted for 10:39 a.m. EDT, the crew was awakened in their quarters in the Operations & Checkout (O&C) Building at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. After showering, breakfasting, and donning their bright orange Launch and Entry Suits (LES), they departed the O&C to the cheers of spectators and well-wishers and boarded the Astrovan for the journey to the launch pad. Upon arrival, they were assisted into their seats aboard Discovery. At 10:30 a.m., the countdown emerged from its final pre-planned hold at T-9 minutes. It was time to get serious.

“Okay, folks, we’re countin’,” Ascent Flight Director LeRoy Cain told his team in the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, which would oversee STS-114 from liftoff through landing. Poignantly, Cain had also been the Entry Flight Director during Columbia’s ill-fated return from orbit, almost 30 months earlier. At T-5 minutes, from the pilot’s seat on Discovery’s flight deck, Kelly cleared the Caution & Warning (C&W) memory and verified no unexpected errors. The seven astronauts were instructed to close their visors and initiate the oxygen flow into their suits.

At T-31 seconds, the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS) transferred primary control of critical events over to the shuttle’s on-board computers, as the pivotal event of “Autosequence Start” occurred. The silence and focus in Mission Control was palpable, as just a handful of clipped messages—“GLS is Go for Main Engine Start,” “Vents are open,” “Copy, vents,”and finally the electrifying “Liftoff Confirmed,” to which Cain responded with a calm “Copy, Liftoff”—passed over the flight loop. In the seconds that followed, as the first shuttle since the loss of Rick Husband and his crew speared toward orbit, the voice of Eileen Collins crackled into the deathly stillness of the control center.

“Houston, Discovery, Roll Program!”

“Roger Roll, Discovery,” replied Capcom Ken Ham.

“Guidance sees a good roll,” confirmed the Guidance, Navigation and Control (GNC) Systems Engineer.

“Copy,” responded Cain.

Within nine minutes, Eileen Collins and her crew achieved a safe orbit, tracking a docking at the space station on 28 June. “We know the folks on Planet Earth are just feeling great right now,” she told Mission Control a few minutes after reaching orbit. Summarizing the day’s dramatic events, NASA Administrator Mike Griffin stressed the difficulties involved in bringing the combined talents of thousands of people, across the United States, together to accomplish the successful launch. “I want you to think about what it takes to get millions of different parts from thousands of vendors across the country to work together to produce what you saw here today,” he explained, “and to realize how chancy it is, how difficult it is, at what a primitive state of technology it still is. The team managed to do it and I think a large debt of appreciation is due to them.”

However, all was not entirely well. Despite having been extensively photo-documented throughout its ascent—and with ice-reduction heaters and a digital still camera aboard the External Tank (ET) for the purposes of precluding foam loss and acquiring unprecedented imagery—it became clear during Discovery’s two-day transit to the ISS that a small fragment of foam had fallen away from the tank. It did not appear to have impacted the orbiter, but NASA was quick to stress that subsequent shuttle missions would be placed on indefinite hold until the incident had been properly understood and corrective actions taken. Immediately after achieving orbit, astronauts Noguchi and Thomas used hand-held video and digital still cameras to document the just-jettisoned ET for downlink to a team of more than 200 specialists for analysis.

“We actually do … a 120-degree maneuver to get to look at [the tank], which has always been true, except now we’re doing it about a minute and 45 to two minutes after Main Engine Cutoff … as opposed to four minutes, which we used to do,” explained Kelly in his pre-flight NASA interview. “We’re also going to do a faster pitch maneuver, the bottom line being that we get to see the External Tank from a lot closer, about one-third to one-half the distance we did before, so we should get a lot-better-resolution pictures from that.” Coupled with these images, the new sensors behind the Reinforced Carbon Carbon (RCC) panels of the wing leading edges took data throughout the ascent and, from the second day of the flight, a series of inspections with the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS). During the journey to the ISS, the crew deployed the 50-foot-long (15-meter) OBSS, which acted as an extension to the shuttle’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm, and was tipped with lasers and other tools to inspect the surfaces, including the critical RCC of the nose cap and wing leading edges, and acquire two- and three-dimensional imagery.

“The process for going out and scanning was very difficult to come up with; the trajectories you have to fly to make sure you cover all of the areas and don’t miss anything … was very difficult,” Kelly said. “The actual operation can become very tedious. You’re doing the same thing over a long stretch of time. However, you’re very close to the orbiter, so if we’ve got this boom and it’s only 5 feet (1.5 meters) away from the orbiter, if it starts doing the wrong thing, instead of looking for damage, we could be causing damage. So over that long period of time that we’re doing this we have to stay sharp to make sure if anything goes wrong we can actually safe the system before any damage occurs.” Much of the OBSS data was downlinked in real time and the remainder was in the hands of flight controllers by the time the crew bedded down for their second night’s sleep in orbit.

Discovery’s docking with the ISS on 28 July differed visually from her predecessors, for although Collins followed the “R-Bar”—or “Earth Radius Vector,” approaching the station from “below” and thus exploiting the “gravitational gradient” to brake her ship’s final approach—STS-114 was also the first mission to demonstrate a novel Rendezvous Pitch Maneuver (RPM). After docking, the crew was welcomed aboard the ISS by the incumbent Expedition 11 crew of Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev and U.S. astronaut John Phillips and pressed immediately into a heavy workload of installing the Italian-built Raffaello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) and the External Stowage Platform (ESP)-2, transferring cargo between the shuttle and the station and executing three ambitious EVAs by Robinson and Noguchi, which included evaluations of new tile-repair techniques.

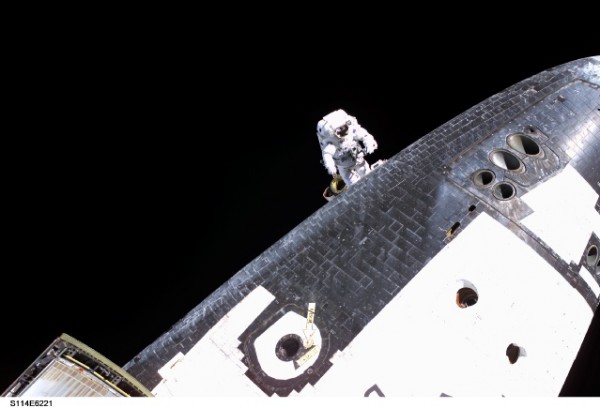

Although the inspections of the shuttle’s surfaces allowed flight controllers to pronounce Discovery fit for re-entry, the awareness that future missions would be suspended prompted a decision to extend STS-114 by one day to provide additional support to the Expedition 11 crew. On their third EVA, Robinson and Noguchi were tasked with removing a pair of thin Nextel fabric gap fillers, which protruded from between thermal tiles on the forward area of the shuttle’s underside. In a press briefing before the spacewalk, Space Shuttle Deputy Program Manager Wayne Hale explained that the level of uncertainty involved in flying a re-entry with protruding gap fillers made it an easy decision to remove them. The repair proved a great success—“It looks like this big patient is cured!” Robinson exulted at one stage in the proceedings—and marked the first time that a shuttle crew had actively participated in the repair of their spacecraft in orbit.

A fourth EVA to tend to a puffed-out thermal blanket above the commander’s window proved unnecessary, and, after unberthing the Raffaello MPLM and returning it to the payload bay, Discovery undocked from the ISS on the morning of 6 August to begin her voyage back to Earth. Originally targeted to touchdown on the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida on the 8th, unpredictable cloud cover in Florida led the Mission Management Team (MMT) to wave the crew off by 24 hours. Although Florida remained the preferred End of Mission (EOM) destination, two more attempts on 9 August were also waved off, and Collins and Kelly brought Discovery home to Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., alighting on Runway 22 at 5:11 a.m. PDT (8:11 a.m. EDT). “A wonderful moment for us all,” was how Eileen Collins summarized the return from space.

In the days, weeks, and months to come, the shuttle fleet would again progress through engineering assessments and ET modifications to understand the foam-loss issues from STS-114. Most alarming was a 0.9-pound (0.4-kg) chunk which fell from the Protuberance Air Load (PAL) ramp—a component intended to smooth the supersonic airflow over a cable tray and a pair of pressurization lines—on the tank, just a couple of seconds after the separation of the twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). Atlantis had been earmarked to fly the second post-Columbia test mission, STS-121, in September 2005, but was indefinitely stood down, initially into the spring, and eventually the summer, of the following year.

As circumstances transpired, STS-121 flew on 4 July 2006 and its astronauts became the first Americans ever to launch on Independence Day. And just as Independence Day was a new start for a fledgling nation, so this event marked a new start for the remaining shuttle flights to come. Having so expertly paved the way for a resumption of missions on STS-114 and STS-121, another 20 flights—seven apiece by Discovery and Atlantis and one by Endeavour—would spear for the heavens between September 2006 and July 2011, completing the assembly of the ISS and preparing for the journey beyond.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the controversial cancelation of the final two Apollo lunar landing missions, 45 years ago, in the summer of 1970.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace