Ten years ago today, Space Shuttle Discovery broke the shackles of Earth under her own power for the final time, to close out a remarkable chapter in U.S. exploration of the heavens. Her launch on STS-133—an ambitious voyage to the International Space Station (ISS), tasked with delivering the final permanent pressurized element of the U.S. Operational Segment (USOS)—marked the 39th mission in a career which had seen Discovery break, and re-break, record after record.

And when she touched down for the final time, two weeks later, her triumphant return was echoed by the NASA commentator’s words: “To the ship that has led the way, time and time again, we say farewell”.

Discovery was not the first shuttle to take flight; that accolade goes to her sister Enterprise, which completed a series of Approach and Landing Tests (ALTs) at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., in the summer and early fall of 1977. Nor was she the first to reach space; for that accolade went to another sister, Columbia, which—after an extensive and agonizing test campaign—flew the shuttle’s maiden foray into low-Earth orbit in April 1981.

Discovery, in fact, was the third of NASA’s fleet of spacegoing orbiters to come off the production line and made her first mission in August 1984. It was the dawn of an almost-three-decade career which saw Discovery log 39 missions, spend a cumulative 365 days in space, circle the globe 5,830 times and travel 149 million miles (238 million km).

Across that bundle of years, she deployed no fewer than 31 satellites—including NASA’s showpiece Hubble Space Telescope (HST)—and her crews included both the youngest and oldest humans ever to launch aboard a U.S. spacecraft. She flew both Return to Flight (RTF) missions after the tragic losses of Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003.

She serviced Hubble more times than any of her sisters. She made the shuttle’s first rendezvous with another inhabited object in space and flew a dozen times to the International Space Station (ISS), delivering cargo, supplies, humans and both the Harmony node and Japan’s Kibo lab to the sprawling orbital outpost.

Her predominantly U.S. crews were also joined by representatives from France and Saudi Arabia, Germany and Canada, Spain and Japan, Switzerland and Sweden, Russia and Italy. As well as playing a key role in establishing an international presence off-world, Discovery was truly an international machine.

But with the loss of Columbia, the end drew inexorably close and plans were set in motion to retire the shuttle fleet by 2010. And when STS-133 Commander Steve Lindsey, Pilot Eric Boe and Mission Specialists Nicole Stott, Tim Kopra, Al Drew and Mike Barratt were assigned to her final flight in September 2009, there was an expectation—however briefly—that theirs might also be the swansong of the program itself.

Originally tasked with lifting payloads and supplies aboard the Italian-built Leonardo Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM), this expansive cargo carrier was later modified to become a Permanent Multipurpose Module (PMM). It would be attached to the ISS and left in place to provide a storage facility for successive station crews.

Unfortunately, STS-133 was a long time coming. And it also fell foul to more than its fair share of misfortune along the way.

Anticipating a launch in the first week of November 2000, the six astronauts flew their T-38 Talon jets into the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida in early October for the customary Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test (TCDT), passing over historic Pad 39A and Discovery as they did so. After their TCDT responsibilities were complete, they returned to the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, but were back on the Space Coast by month’s end for what they anticipated would be a dramatic two-week mission to close out Discovery’s remarkable career.

But it seemed that the shuttle herself was conspiring against them. On 14 October, a small leak was discovered in a monomethyl hydrazine feedline leading to the aft-mounted Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS). An air half coupling flight cap was replaced in an attempt to solve the problem, but traces of a leak remained. Engineers next torqued six bolts around a suspected leaky flange fitting.

Again, evidence of a leakage manifested itself. Finally, both left and right OMS pods were drained of their propellants—monomethyl hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide—and efforts got underway to effect a fix on the launch pad. Two seals on the right-hand OMS pod’s crossfeed flange were removed and replaced and tests indicated that they were properly seated, were satisfactorily holding pressure and wre exhibiting no evidence of further seepage.

As October wore into November, an electrical issue arose with a backup Main Engine Controller (MEC) on Discovery’s right-hand Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME). Then a leak was found at the Ground Umbilical Carrier Plate (GUCP), the interface between the External Tank (ET) and the 17-inch-diameter (43 cm) pipeline responsible for transporting gaseous hydrogen out to a flare-stack to be harmlessly burned off.

The GUCP was duly replaced, but shortly afterwards a cracked flange between the ET’s liquid oxygen tank and instrumentation-laden “inter-tank” was discovered. The latter was the first (and last) case in which cracks had been found on the ET, whilst on the launch pad. Structural “radius-blocks” were subsequently installed onto the tank’s structural stringers, but for STS-133 the result of this raft of problems was a postponement until February 2011.

And that spelled bad news for Mission Specialist Tim Kopra.

In the middle of January, he sustained an injury whilst bicycling near his Houston home, whose severity was such that it demanded a replacement astronaut be assigned in his stead. Since Kopra was STS-133’s flight engineer and chief spacewalker, it was a highly inopportune moment for a crew swap. Veteran spacewalker Steve Bowen, who had flown only months before on STS-132, was named and began training alongside Lindsey’s crew for the next five weeks leading up to launch. It marked the shortest interval between assignment to flight of any U.S. astronaut in the shuttle program.

Launch on 24 February 2011—a decade ago, today—was targeted for 4:50 p.m. EST, but the countdown clock was held for several minutes in response to a minor glitch in systems used by the Range Safety Officer (RSO). It was decided to count down to T-5 minutes and hold the clock until the safety console was in position to either declare itself “Go” or “No-Go” to support the launch.

As the minutes ticked by, there were words of encouragement, including from the workforce which had committed their lives to getting the shuttle ready. “From the processing team of Discovery, to the crew of Discovery, enjoy the ride.”

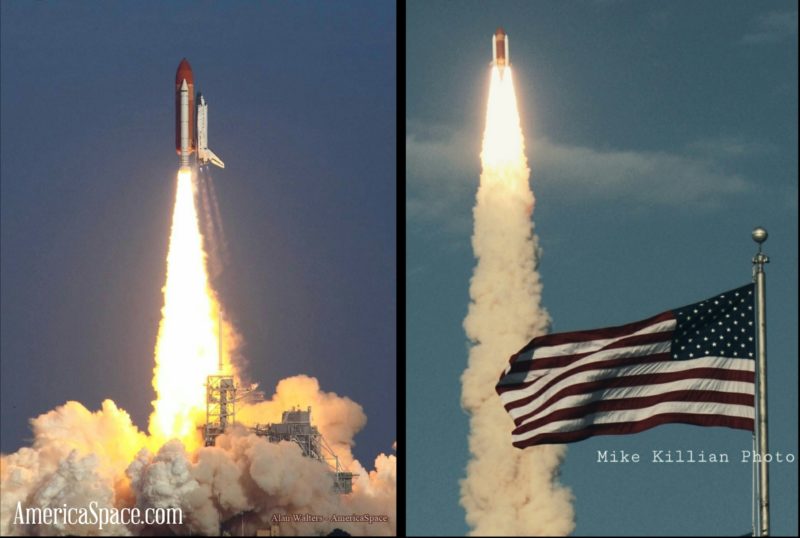

“Thanks for all the work you did for getting us ready to go,” replied Lindsey from the flight deck. “And for those watching, get ready to watch the majesty and the power of Discovery, as she lifts off one final time.”

Passing T-5 minutes, the Range declared itself “Go” and Boe was instructed to activate the shuttle’s Auxiliary Power Units (APUs). The seconds ticked downward, with consoles in Mission Control having identified themselves as Green. Orbiter Test Conductor (OTC) John Kracsun asked Boe to clear Discovery’s caution-and-warning memory. Boe swiftly executed the task and came back with a brisk status update for Kracsun: “No unexpected errors.”

Inside one minute before launch, with the liquid oxygen and hydrogen tanks in the ET verified at the proper flight pressures, the Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) joint heaters were deactivated as intended. At T-31 seconds, the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS) transferred authority over to the Autosequencer, with the shuttle now overseeing the countdown. “Discovery’s on-board computers now have primary control of all the vehicle’s critical functions,” came the call.

“Twenty seconds,” intoned the launch announcer. “The sound suppression water system has been activated, protecting Discovery and the launch pad from acoustical energy waves.” Next up was the ignition of the three main engines and their 1.2 million pounds (540,000 kg) of propulsive yield, almost a quarter of the power needed to reach orbit. In Mission Control, the atmosphere was an oxymoronic one of calm tension.

“Three engines ready,” the Booster Officer advised Jones. “Copy, three ready,” the flight director responded with a nod. At T-10 seconds, a swirl of sparklers—the burn-off igniters—hissed and came alive beneath the three main engines to clear excess quantities of unburnt hydrogen. “Go for Main Engine Start”, came the call as the SSMEs roared to life and ramped smoothly up to full throttle. “Two…one…zero…booster ignition…and the final liftoff of Discovery,” he exulted. “A tribute to the dedication, hard work and pride of America’s Space Shuttle Team. The shuttle has cleared the tower!”

In the windowless Mission Control, almost a thousand miles (1,600 km) to the northwest, Jones’ team received a “Liftoff Confirmed” call, as they waited for Lindsey to perform his first post-launch radio communication.

“Houston, Discovery, Roll Program,” radioed Lindsey, as the vehicle cleared the Pad 39A tower and rolled over onto its back to begin the uphill climb.

“Roger Roll, Discovery,” replied the unflappable Capcom Charlie Hobaugh, seated at his console in Mission Control.

And “unflappable”, indeed, would go on to characterize the rest of STS-133’s climb to orbit. The twin SRBs were jettisoned as planned at two minutes into flight, after which Lindsey and his crew rode the almost-electric sensation of the main engines for a further six minutes. Shutdown came perfectly at 8.5 minutes after liftoff and Discovery was in space for the 39th and last time in her career. Ahead of her lay a hugely complex and intricate two-week mission, a pair of spacewalks and the installation of a new module onto the ISS. But on 24 February 2011, one of the most dangerous events of any shuttle mission—the launch—was now behind them.

“Welcome to you and your veteran crew, back to space,” radioed Hobaugh.

“Thanks a lot,” replied a now-weightless Lindsey. “Good to be here.”

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.