Only five U.S. astronauts in history—most recently Kate Rubins in 2020—have launched into space on their birthday. On 7 August 1997, a quarter-century ago today, Kent “Rommel” Rominger suited up to launch aboard shuttle Discovery on his special day, for an ambitious mission to deploy and recover an atmosphere-watching satellite and support a range of scientific and technical experiments in support of future International Space Station (ISS) operations. But were it not for fate, Rominger would not have been aboard Discovery at all that day, for a dark strain of tragedy lay at the very heart of STS-85.

When Discovery’s five-member “core” crew—Commander Curt Brown, Pilot Jeff “Bones” Ashby and Mission Specialists Jan Davis, Bob Curbeam and Steve Robinson—were assigned to the flight in September 1996, they anticipated launch the following summer. A few weeks into their training flow, they were joined by Canadian Payload Specialist Bjarni Tryggvason.

Then, in March 1997, only months before launch, STS-85 changed markedly with the illness and subsequent death of Ashby’s young wife. Ashby requested reassignment and his place on the mission was taken by veteran pilot Rominger.

To protect Ashby’s privacy, NASA revealed only that he had been reassigned to an administrative role as assistant to the director of the Flight Crew Operations Directorate (FCOD). But Ashby’s wife, Diana, was in the final stages of a terminal cancer diagnosis, a dreadful disease which sadly claimed her life on 2 May 1997.

“Her one-liners and short quips began when she awoke each morning of her life and continued until her last breaths,” Ashby told the Melanoma Research Foundation, which Diana founded. It was Diana who told her sisters to throw a big party each year in her honor…and send the bill to Ashby himself. “Diana found humor to be a great medicine,” Ashby recalled.

Early on 7 August 1997, birthday balloons and a small cake sat atop the breakfast table as Rominger and his crewmates posed for photographs, ahead of suiting up. “We got Beamer away from the breakfast table,” quipped Brown of Curbeam’s seemingly insatiable appetite. After donning their bright orange pressure suits, the six astronauts departed the Operations & Checkout (O&C) Building, bound for historic Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) and their trusty ship, Discovery.

A brief worry about ground fog threatening visibility at the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) proved unfounded and at T-2 minutes the crew was instructed to close and lock their visors. It furnished a nice opportunity to wish Rominger—who went by the nickname of “Rommel”—a happy birthday.

“On behalf of the launch team, good luck with your mission,” came the final bon voyage call, “and Rommel, happy birthday. We’re about to light your candles.”

“They’ll be the two best candles I ever had,” replied Rominger. And without further ado, at 10:41 a.m. EDT STS-85 went smoothly airborne, at the start of a 99-minute “window”. From the flight engineer’s seat, Curbeam was surprised by the dynamism of the event.

“The simulator…really doesn’t do the trip justice,” he said later. “It’s just extremely exciting. I can’t describe how great it felt…and how exhilarating the acceleration on my chest felt.” As Discovery commenced her computer-commanded “roll program” maneuver, to set her onto the proper azimuth for a 57-degree-inclined orbit, Davis, sitting next to Curbeam on the flight deck, found the Sun directly in her face for the entirety of ascent.

But upon reaching orbit, there was little time for sightseeing. Davis and Robinson quickly set to work activating Discovery’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) robotic arm to deploy the Shuttle Pallet Satellite (SPAS). It was laden with a battery of sensors and instruments collectively known as the Cryogenic Infrared Spectrometers and Telescopes for the Atmosphere (CRISTA).

Flown once before, CRISTA-SPAS sought to gather global data on “middle-atmosphere” trace gases at near- and far-infrared wavelengths. Also aboard CRISTA-SPAS was the Middle Atmosphere High Resolution Spectrograph Investigation (MAHRSI), a U.S. Naval Research Laboratory experiment to observe ultraviolet emissions from nitric oxide and hydroxyls in the middle atmosphere and lower thermosphere.

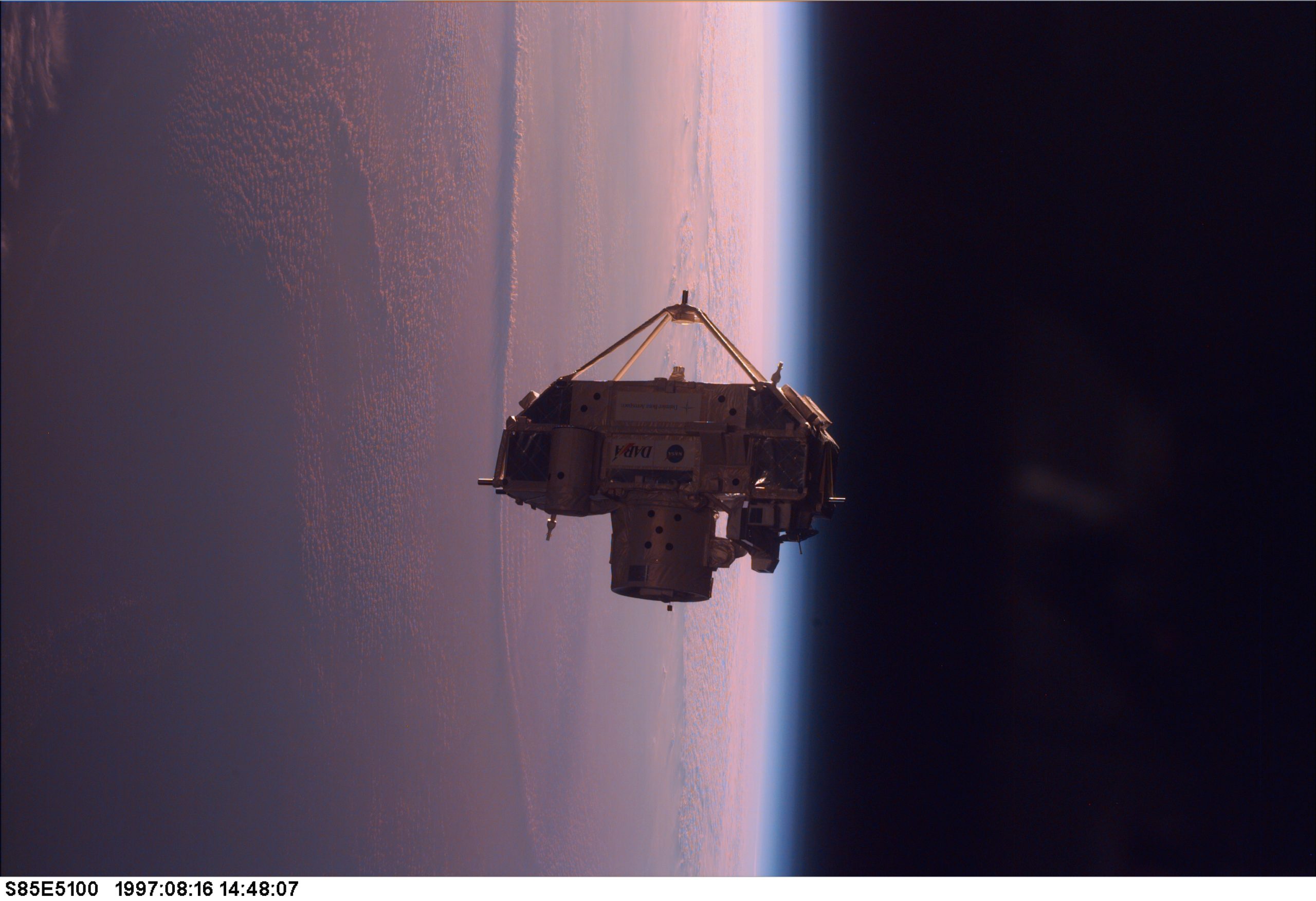

A brief communications glitch delayed the CRISTA-SPAS deployment by 30 minutes, but Davis set it free at 7:27 p.m. EDT, just under nine hours into the flight. The satellite would fly in formation with the shuttle for 200 hours, before being retrieved and brought back into Discovery’s payload bay on the tenth day of the mission.

As circumstances transpired, CRISTA-SPAS maintained an average distance of 50-70 miles (80-110 kilometers) before rendezvous and capture by Davis at 11:13 a.m. EDT on 16 August. Unlike most earlier shuttle rendezvous, which approached their targets from “below”, along the Earth Radius Vector—the so-called “R-Bar”—STS-85’s retrieval of CRISTA-SPAS demonstrated a Twice-Orbital-Rate Fly Around (TORFA) technique.

It started in a fashion not unlike the R-Bar, with Brown flying Discovery towards the satellite from “below”, until 500 feet (150 meters). Next, Brown initiated a fly-around of the satellite, to position the shuttle onto the Velocity Vector (“V-Bar”), a 90-degree angle change.

“Once we get to the V-Bar, we’ll stop there and fly in on the V-Bar…on into grapple range,” he said. “That is what we do on our normal space station rendezvous. We have corridor requirements and we have closure requirements that we must meet.”

TORFA, added Rominger, enabled the crew to “actually hop over the top of CRISTA and do a full-circle loop, all the way back around it, stop and come up from below for a while, then continue that full-circle loop back around to being out in front of it again”. By this stage, Discovery flew about 330 feet (100 meters) from the satellite and Brown inched closer to a capture distance of 33 feet (10 meters). That enabled Davis to grab it with RMS and berth it safely into the shuttle’s payload bay.

Yet a wide range of other payloads—around 40 in total—also dominated the astronauts’ time during STS-85. Japan provided the Manipulator Flight Demonstration (MFD), a trial of the small fine robotic arm which was then under consideration for the ISS.

The arm included shoulder roll and pitch joints, an elbow pitch joint and a wrist pitch and yaw joint. But data conflicts prevented Davis and Robinson from grappling a simulated Orbital Replacement Unit (ORU) box and opening a hinged experiment door.

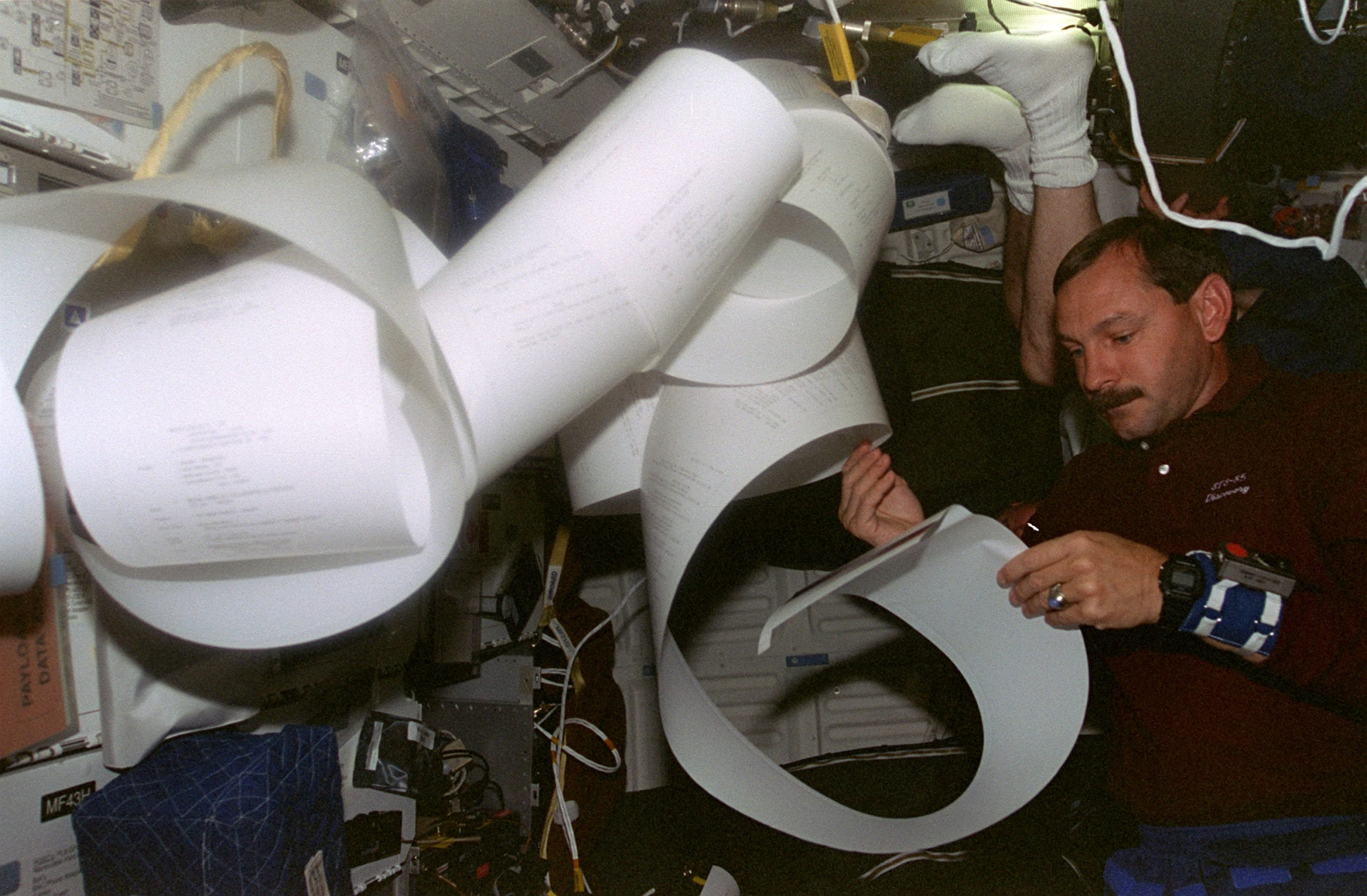

Elsewhere in Discovery’s payload bay, other experiments ranged from studies of the solar constant to infrared observations of terrestrial cloud structures and from examinations of the viscosity of xenon at its critical liquid/gas point to novel thermal control and cooling systems, accelerometers and laser altimeters. Curbeam worked extensively with a middeck bioreactor, which grew colon cancer cells, whilst Robinson worked with a large wide-field ultraviolet camera to capture 430,000 images of Comet Hale-Bopp.

Canada’s Tryggvason also had his own plate of research activities, including the Microgravity Isolation Mount (MIM). Tryggvason’s Icelandic heritage had seen Iceland’s then-president, Olafur Ragnat Grimsson, visit KSC to watch Discovery’s launch.

“We are a culture of settlers created from the old days of the sagas,” said Grimsson, “and we see Bjarni Tryggvason as a direct descendent over the great discoverers of the Viking period. I think it’s almost a divine indication that the name of the shuttle should also be Discovery.”

Extended from 11 to almost 12 days, the long mission gave the STS-85 crew a chance to reflect on where they truly were. “One thing that you do notice is that your problems, although they seem large to you, are very, very small in scope,” said Curbeam.

“That is something that you realize, just how insignificant you are in the big scheme of things when you go up into space and look back on the Earth. That was the feeling I got.”

After what Brown described as a mission which offered “a perfect example of the versatility and the capabilities of the Space Shuttle”, its 40-plus payloads reflecting the efforts of six sovereign nations, the time came to return home. Delayed from an 18 August landing by a threat of ground fog at KSC, Discovery re-entered the atmosphere early on the 19th and touched down smoothly on Runway 33 at 7:07 a.m. EDT, a few hours shy of 12 full days since liftoff.

Declaring that it was good to be home, for STS-85’s first-timers—Robinson, Tryggvason and Curbeam—the immense amount of work completed was highly satisfying. But it was far outpaced by the once-in-a-lifetime experience of seeing the Home Planet as God himself might see it.

“I think the biggest impression that I left with from that flight,” Curbeam said later, “although we did a lot of work in the sciences, was just the view. It’s absolutely incredible!”