When Kate Rubins launched last month to the International Space Station (ISS), she became only the fifth American (and the first U.S. woman) to do so on a birthday. Only four other astronauts—Dick Truly, Kent Rominger, John Phillips and Dale Gardner—have managed a similar feat, and it was on this day, way back in 1984, that Gardner launched aboard shuttle Discovery on one of the most audacious missions of all time. Together with STS-51A crewmates Rick Hauck, Dave Walker, Joe Allen and Anna Fisher, he would triumphantly deploy two communications satellites and salvage two others, in one of the most spectacular and memorable flights of the decade.

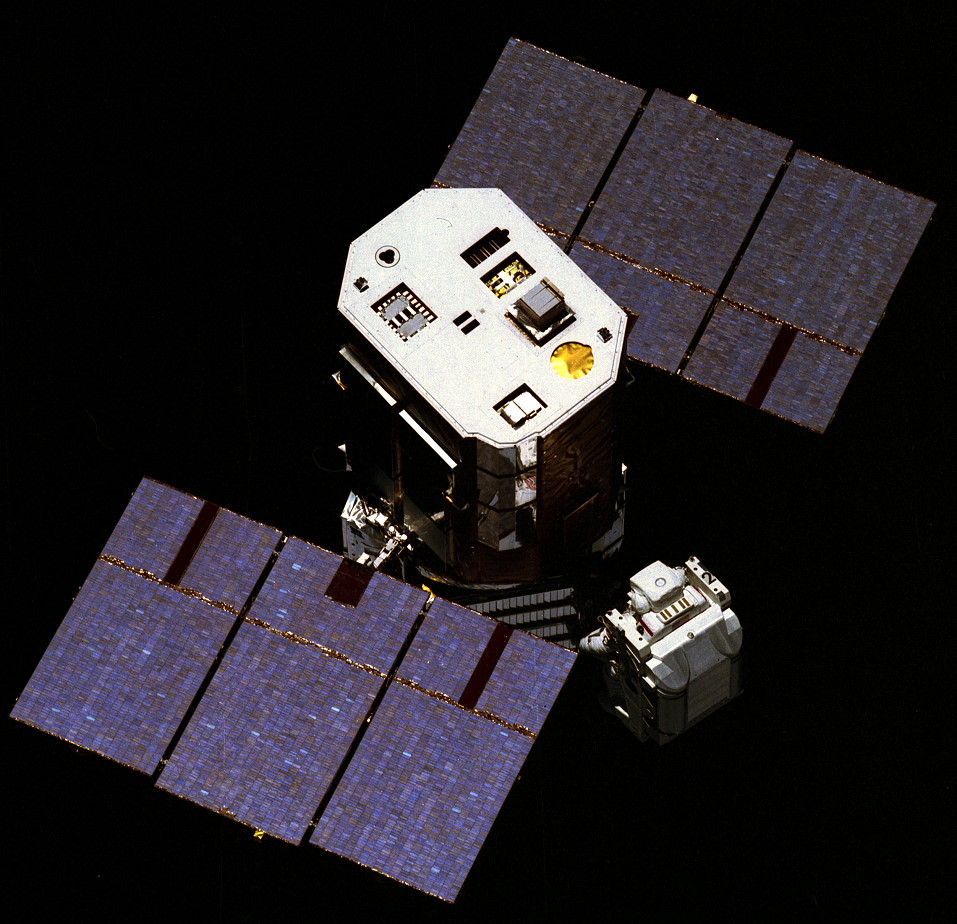

Westar-VI and Palapa-B2 were owned by Western Union and the Indonesian government. When fully deployed in their operational 22,300-mile (35,900-km) geostationary orbits, they each measured 22 feet (6.7 meters) tall and took the form of enormous cylinders, coated with hundreds of solar cells.

They had been launched aboard shuttle Challenger in February 1984, but within minutes of deployment their attached Payload Assist Module (PAM)-D boosters failed to push them out of low-Earth orbit. It was not possible to use the satellites’ own motors to lift them to geostationary altitude, but NASA’s Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU)—a jet-propelled backpack used effectively in April 1984 to service the Solar Max observatory—planted the seed of an idea for a shuttle rescue mission.

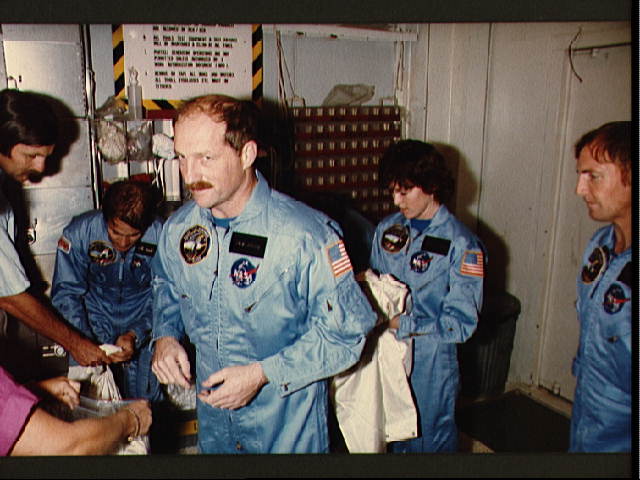

Hauck, Walker, Allen, Fisher and Gardner had already begun training together in late 1983 for another flight and by March 1984 they had been informally tipped for the Palapa/Westar task. “I think there were a number of things that worked in our favor,” said Hauck in a NASA oral history interview. “One was just the timing of our mission. I had flown proximity operations on STS-7. Clearly, prox-ops would be necessary to do this mission.” Another was the successful Solar Max repair and yet another was the performance of the MMU, the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm and the superior work of the spacewalkers.

But there was a problem. Neither Palapa or Westar was designed to be captured in space and it was necessary to build a mechanism to snare them. One morning, Gardner arrived at work in a state of excitement. Years later, Hauck could not be sure if it was Gardner alone or in conjunction with the Extravehicular Activity (EVA) equipment team which came with the idea, but the consensus was to fabricate a probe-like “stinger.” Six feet (1.8 meters) long, it was called the Apogee Kick Motor Capture Device (ACD) and would be attached to the arms of the MMU.

“The astronaut could then fly the stinger into the satellite’s rocket nozzle,” wrote Allen in his memoir, Entering Space. “Once inside, he could release a lever that would allow toggle fingers to expand, much like opening an umbrella inside a chimney. A hand-driven crank would shorten the length of the stinger and pull the satellite against a padded ring at the stinger’s base. The satellite would be held securely and the astronaut could then use the MMU’s thrusters to stop its tumbling and hold it while the [RMS] grabbed a grapple fixture on the stinger.”

It seemed fairly straightforward, but for one thing: Only the nozzle “end” of the satellites could be clamped into the payload bay for the return to Earth; therefore, some other technique would be needed to temporarily “hold” them in place whilst the stringer was detached and a cradle adaptor fitted.

NASA’s solution was for an aluminum A-frame (properly termed the “Antenna Bridge Structure”) to be placed over the delicate antenna at the “top” of each satellite. “Next, the arm would take hold of a grappling pin on the A-frame,” concluded Allen, “keeping the satellite motionless while two astronauts manually fitted the adaptor at the nozzle end.” With the adaptor in place, the RMS would lower the satellite into position in the bay and the spacewalkers would finally remove the A-frame.

By September 1984, recovery contracts had been signed with Palapa and Westar’s insurance underwriters, the equipment had passed thermal vacuum chamber tests and the satellites themselves had been lowered in altitude to about 220 miles (350 km) in order for the shuttle to reach them. After being scrubbed due to high winds, STS-51A launched on 8 November 1984 and successfully deployed its own payload of two communications satellites in the first two days, before setting off in pursuit of Palapa and Westar.

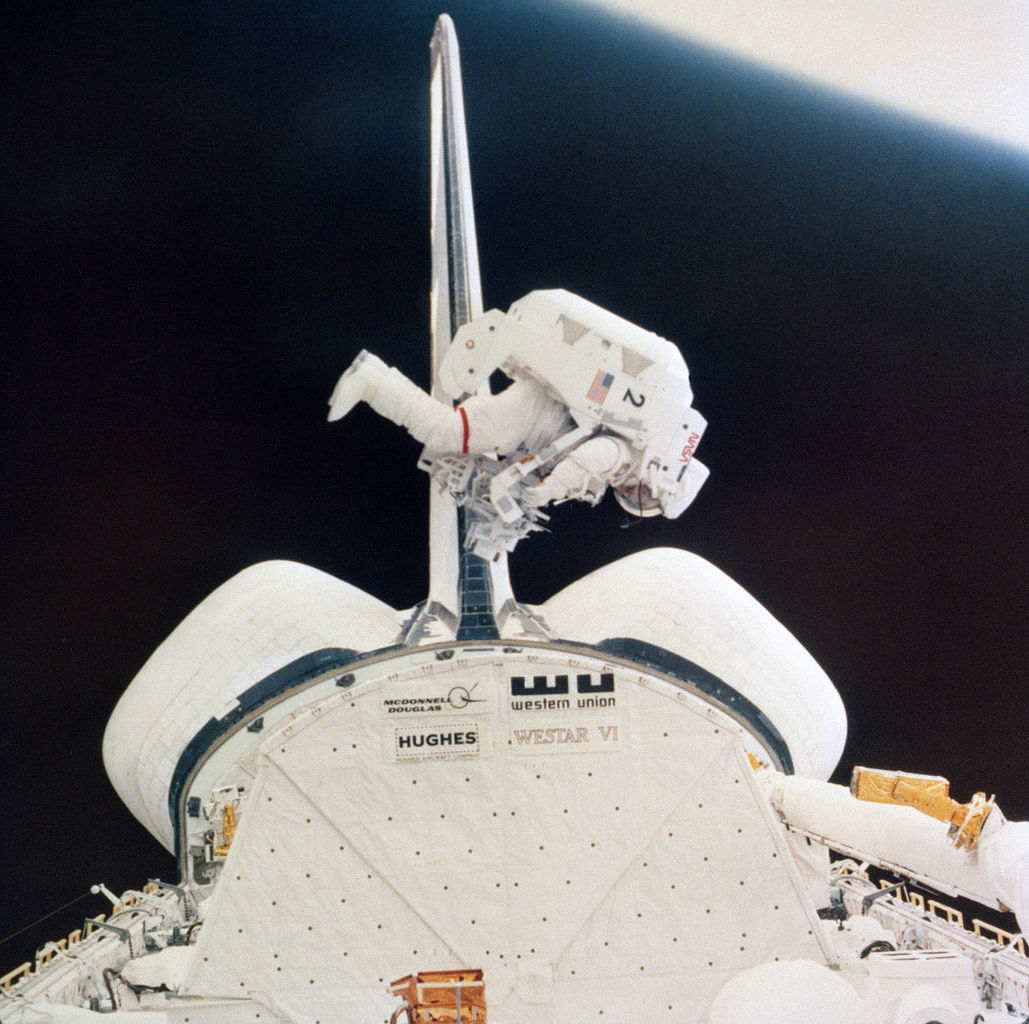

Early on the 12th, the crew guided their ship up to Palapa. At 8:25 a.m. EST, a spacesuited Allen pushed open the shuttle’s airlock hatch and was rewarded not only with a faceful of outer space, but also a faceful of satellite, directly over his head. As orbital darkness fell, he buckled himself into the MMU, tested its propulsion systems, released its bulkhead lever and glided like Buck Rogers across Discovery’s payload bay. Gardner attached the stinger to the arms of the MMU and Allen flew smoothly over to the slowly spinning satellite.

At first, as he headed around the “base” of Palapa, he was struck full in the face by blazing sunlight, but as he drifted closer and closer and finally entered its shadow, he could instantly see clearly and guided the stinger home. Allen waited a few seconds as the stinger moved further and further into place, then pulled the lever to open the toggles.

“Stop the clock,” he yelled, triumphantly. “I’ve got it tied!”

A few minutes later, Fisher guided the RMS grapple fixture over a pin on the stinger. Returning to the payload bay, Allen doffed the MMU and positioned himself in a portable foot restraint on the end of the mechanical arm, then watched as Gardner attached the A-frame over Palapa’s fragile antenna.

Suddenly, they hit a glitch. A rigid structure, part of the satellite’s wave guide equipment, was protruding farther outboard than had been expected and the A-frame would not fit. It was Walker who suggested that their only option was for Allen to physically grab the antenna “end” of Palapa and hold it steady, whilst Gardner single-handedly attached the adaptor. “Dave Walker…was the keeper of all the Plan Bs that we had devised,” Allen told the oral historian, “and we’d written them down. It was, sad to say, written on Dave’s piece of paper just as Improvise!”

For 90 minutes, Gardner worked, finally declaring success by manually tightening nine bolts around the edge of the adaptor. Shortly thereafter, the two men moved Palapa into a vertical position and lowered it into the bay, securing it in place with payload retention latches. Years later, Allen paid tribute to Gardner’s diligence and persistence in getting the job done, working alone. The first EVA lasted exactly six hours.

Their next step was to rendezvous with Westar and Mission Control brought the troubling news that it, too, had wave guide equipment in the same place. Consequently, it was decided that Gardner would fly the MMU out to the satellite and Allen would act as a “human” A-frame, holding the antenna end of Westar, whilst the adaptor was fitted. The second EVA duly got underway on 14 November and Gardner quickly captured Westar and returned it to the payload bay. The second retrieval would proceed more smoothly than the first and, in total, the astronauts would spend five hours and 42 minutes outside.

On this occasion, Allen spent a considerable amount of time with his feet secured on the end of the RMS, which gave him a quite different perspective … and made him feel peculiarly precarious.

“Flying the MMU,” he wrote, “much like piloting an airplane, had not imparted an ominous sense of height to me; I was in control and at ease with the responsive machine. But riding the end of the arm, high above the cargo bay, was like standing on the tip of the world’s highest diving board, and a movable board at that.” His limited visibility of his helmet meant that he could not see his feet, nor the rail by his side. “Only my knock-kneed stance kept me in the foot restraint,” he continued, “and my ride was as nerve-wracking as anything I had ever done before.”

Intellectually, Allen knew that he would not fall, but the sensation persisted that if he slipped his restraint, he might either plunge into the payload bay or else directly to Earth. “It was a relief to take hold of the satellite when Dale brought it within my reach,” Allen concluded. “I felt like a man on a high wire, being handed a balance bar, and the round end of the cylindrical satellite provided some comfort and security.”

Gardner finished laboring to attach the adaptor, and the two men proceeded to secure Westar into the bay. It was a triumphant moment. They were out of radio communication with Houston at the time, and, from the flight deck, Hauck told the spacewalkers that he wanted them to announce success at Acquisition of Signal (AOS).

Allen and Gardner declined. After all, it was the captain of a salvage vessel who traditionally must assume such responsibilities. “Rick, that’s the commander’s job,” they told him. “When we come AOS, you report that we have two satellites safely aboard. And you can also use the words F**king Miracle.”

Hauck chuckled at the “inside” joke. It originated a few days before launch. He was already irritated by the media’s assumption that the mission was a piece of cake, with two “easy” satellite deployments and two “easy” retrievals. When a high-ranking NASA official from the Office of Public Affairs called a meeting with them, it was with some trepidation that the crew entered the conference room. Hauck asked for the agenda. The official responded that there was no specific agenda; he had merely come along to wish them good luck.

“We were all surprised,” recalled Allen, “because this really was occupying a good chunk of our morning and time was very important to us right then.” At this point, Hauck recalled the comments from the media that STS-51A was an “easy” mission. “There is something that you can do,” he told the official, and proceeded to cite the “easy” news reports. “I can assure you that none of us said that, nor do we believe it … and I will personally tell you that my assessment is: if we successfully capture one satellite, it will be remarkable, and if we get both satellites, it will be a f**king miracle! You can quote me on that!” And without another word, he ended the meeting.

Now, with this achieved, Hauck kept his language somewhat more appropriate. “Houston,” he radioed at AOS, “we’ve got two satellites, locked in the bay!”

All five of them could hear in their headsets the shouts and cheers from Mission Control. They had done it. Hovering above Palapa and Westar, Gardner now untaped and displayed a sign, emblazoned with the statement: For Sale. The satellites would be returned to Earth, refurbished and launched again several years later.