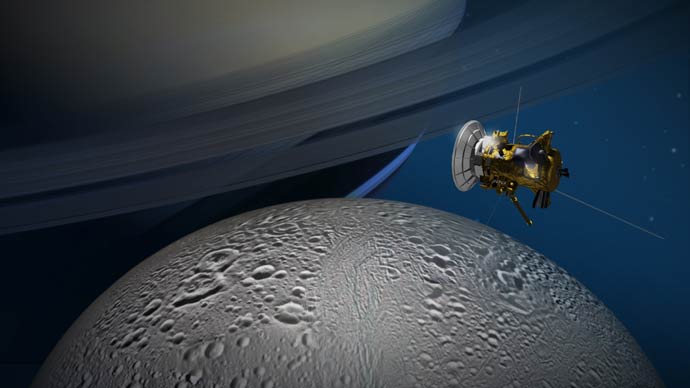

Starting today, the Cassini spacecraft is making the first of three scheduled close flybys of the moon Enceladus, which will provide the first good look at the north polar region of the tiny, water-spraying moon. These will be the final close-up views of this fascinating world during Cassini’s mission, and may help scientists to better understand the potential habitability of Enceladus, which has become a primary target of interest in the search for evidence of life elsewhere.

Images are expected to arrive back on Earth one or two days after today’s flyby. Cassini will pass Enceladus at an altitude of 1,142 miles (1,839 kilometers) above the surface, with closest approach at 3:41 a.m. PDT (6:41 a.m. EDT). The final two approaches will occur in late-October and mid-December.

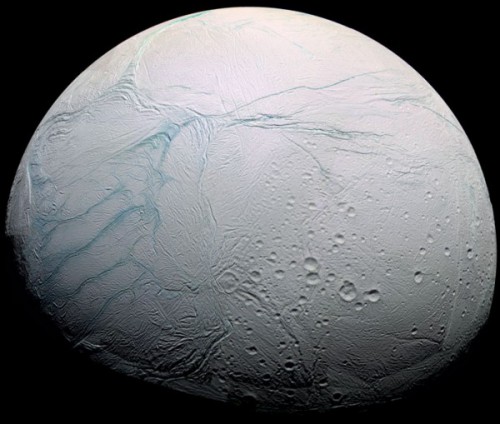

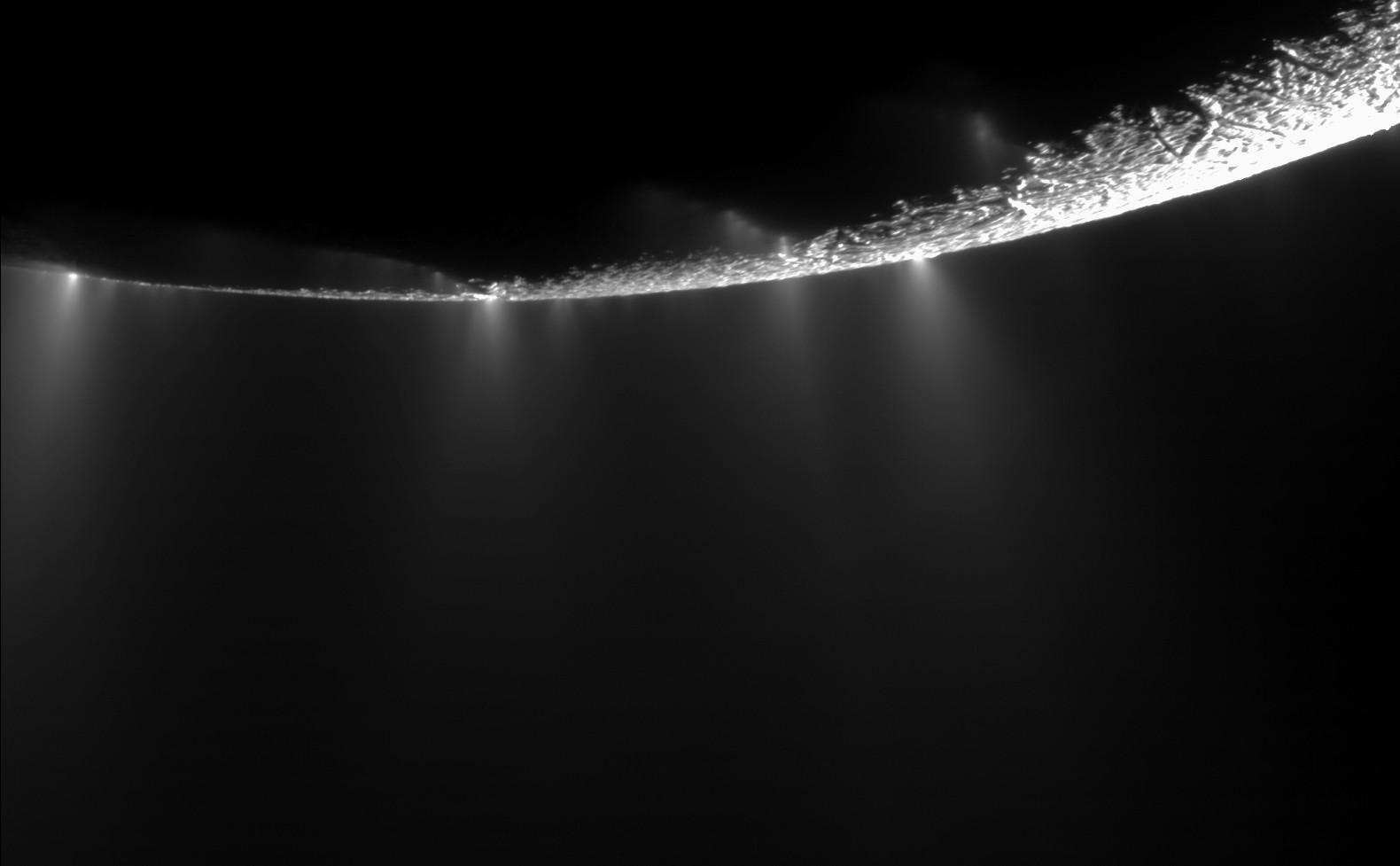

The south pole of Enceladus, where the huge water vapor geysers erupt from deep cracks in the surface, has been studied in detail by Cassini, but this will be the first detailed view of the moon’s north polar region. During previous close approaches, the northern hemisphere was in darkness, but now the region is in summer sun. If there is any similar geological activity at Enceladus’ north pole, Cassini will be in a good position to look for it.

“We’ve been following a trail of clues on Enceladus for 10 years now,” said Bonnie Buratti, a Cassini science team member and icy moons expert at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “The amount of activity on and beneath this moon’s surface has been a huge surprise to us. We’re still trying to figure out what its history has been, and how it came to be this way.”

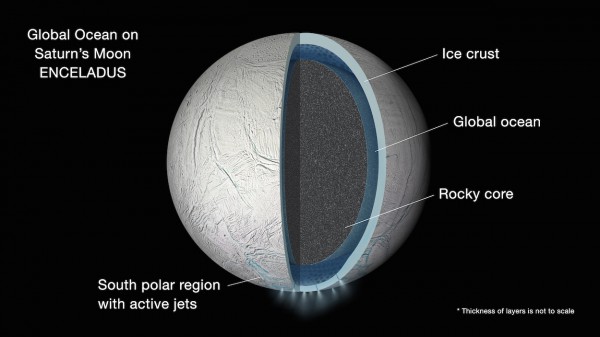

Scientists are eager to learn more about this region of Enceladus, since the activity at the south pole was such a surprise. Enceladus is a very tiny moon, only 313 miles (504 kilometers) in diameter, yet somehow has enough internal energy to power the water vapor geysers which emanate from the “Tiger Stripe” fissures in the surface. Early evidence suggested a subsurface sea under the south polar surface, but now new gravity data indicates that Enceladus has a global subsurface ocean, similar to Jupiter’s moon Europa and possibly other icy moons in the Solar System.

There is also evidence that the ocean is salty, like oceans on Earth, with hydrothermal activity on the ocean floor. On Earth, such locations are teeming with a variety of life forms, but whether this is true on Enceladus is unknown.

“The global nature of Enceladus’ ocean and the inference that hydrothermal systems might exist at the ocean’s base strengthen the case that this small moon of Saturn may have environments similar to those at the bottom of our own ocean,” said Jonathan Lunine, an interdisciplinary scientist on the Cassini mission at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. “It is therefore very tempting to imagine that life could exist in such a habitable realm, a billion miles from our home.”

Cassini has flown directly through the water vapor plumes several times now, and its instruments have detected water vapor, ice particles, sodium, potassium, methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and both simple and complex organics. Two new papers being presented at this year’s American Geophysical Union (AGU meeting)—here and here—discuss the latest findings about organics in the plumes. Cassini isn’t equipped to detect life itself in the plumes, and organics by themselves don’t prove life, but they offer tantalizing clues that life of some kind, at least microscopic, might exist in the waters below the surface.

The next flyby of Enceladus will be Wednesday, Oct. 28, when Cassini will pass only 30 miles (49 kilometers) above the moon’s south polar region, making its deepest dive yet into the plumes. The final flyby will be Friday, Dec. 19, at an altitude of 3,106 miles (4,999 kilometers). That flyby will measure how much heat is coming from the moon’s interior.

An animation of this first flyby has also been posted on YouTube:

There is an online toolkit covering all three flybys available here.

Along with Jupiter’s ocean moon Europa, Enceladus is now considered to be one of the best places in the Solar System to search for evidence of extraterrestrial life. Even if only microscopic, such a discovery would be profound. With growing evidence for oceans inside other icy moons, such as Ganymede and Titan, it seems that such water worlds may be quite common, perhaps in other solar systems as well. It may even be that moons or planets with subsurface oceans are more common than ones with water on their surfaces. Future missions to Enceladus are being considered, such as the Enceladus Life Finder (ELF), which could better study the plumes for evidence of biological activity.

Cassini is approaching the last stages of its mission, scheduled to end in 2017, but scientists will continue to monitor Enceladus and the other moons for as long as possible. Cassini has been orbiting Saturn since 2004, studying the planet, its rings, and moons as never done before. In November, the orbit of Cassini will be raised out of the space near the planet’s equator. There will also be some close flybys of some of the smaller moons which orbit near the rings.

“We’ll continue observing Enceladus and its remarkable activity for the remainder of our precious time at Saturn,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL. “But these three encounters will be our last chance to see this fascinating world up close for many years to come.”

More information about the Cassini mission is available here.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » Europa Mission »

Exciting stuff! More incredible work from JPL’s Cassini team.

What is truly amazing is that the Cassini spacecraft has lasted for so many years, doing amazing science. It is a testament to the engineering of such a talented team. We almost take it for granted.