For more than a decade, we grew used to the sight of shuttles approaching to dock at the International Space Station (ISS). With the exception of five missions, flown between December 1998 and October 2000, when the multi-national outpost was uninhabited, orbiters Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour docked on 31 occasions and their astronauts were welcomed with handshakes and bear hugs by an incumbent expedition crew. At first glance, it might be supposed that the very first shuttle mission to dock with an occupied ISS—STS-97, launched 15 years ago, next week—would have offered the opportunity for an eager hatch-opening and historic welcoming ceremony, before the respective crews settled down to work. But after docking at the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-3 interface at the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the station’s Unity node on 2 December 2000, STS-97 Commander Brent Jett and Expedition 1 Commander Bill Shepherd knew that it would be almost a week before they would be able to gather together for a joint celebration and joint meal. For them, the critical work came first and the celebrations came later.

The reason had a great deal to do with the three critical EVAs to be performed by STS-97 Mission Specialists Joe Tanner and Carlos Noriega to install and activate the $600 million P-6 Integrated Truss Structure (ITS), which carried the first of eight pairs of gigantic, U.S.-built Solar Array Wings (SAWs), together with radiators and ammonia coolant loops, to provide early electrical power for the infant station. Under normal circumstances, both the shuttle and the ISS operated at a “sea-level” atmospheric pressure of 14.7 psi. However, in readiness for EVAs—and in order to minimize the requirement for Tanner and Noriega to pre-breathe pure oxygen for an unduly lengthy period of time, ahead of depressing the airlock—the shuttle’s cabin had to be reduced to 10.2 psi, allowing them, in Jett’s words, to be “much more efficient getting our EVA crew members out the door. Our EVAs are so busy, and those EVA days will be so long, that we felt it was not something we could do. We could not afford to keep the shuttle at 14.7 psi. Since you need different pressures in the two vehicles, the hatches have to stay closed”. Tanner added that pre-breathing in their suits whilst the cabin was at 14.7 psi would require four hours. “That would just kind of blow your whole day,” he told a NASA interviewer. “If we depress at least 24 hours prior to the EVA to 10.2, then we only have to pre-breathe for 40 minutes. We’ll depress actually about 36 hours prior to the EVA and that means that we cannot open the hatch between the station and the shuttle until after the EVAs, when we can safely go back up to 14.7.”

Two hours after Endeavour docked smoothly at the ISS, in the early evening EST of 2 December, STS-97 Mission Specialist Marc Garneau—representing the Canadian Space Agency (CSA)—lifted the P-6 segment out of the shuttle’s payload bay with the Remote Manipululator System (RMS) mechanical arm. Tipping the scales at some 35,000 pounds (15,875 kg), and measuring 45 feet (14 meters) in length, the presence of P-6 made STS-97 the carrier of the second-heaviest shuttle payload at that time, sitting just behind STS-37 in April 1991, which delivered the 37,000-pound (17,000 kg) Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO) into orbit. Garneau positioned the massive truss at an angle of about 30 degrees with respect to the payload bay, where it would be “parked” overnight on the end of the RMS to warm its components, ahead of installation onto the Z-1 ITS segment, atop the space-facing (or “zenith”) face of the Unity node, early on 3 December.

As this work was ongoing, Tanner and Noriega made their way through Endeavour’s docking tunnel and, despite some stubbornness in the hatch—caused by a slight pressure differential between the two spacecraft—briefly entered PMA-3 to leave supplies, including a new laptop, headsets for the station’s two-way videoconferencing system, a new hard drive for a Russian computer, several large bags of water, a pair of vice-grip pliers, packaged food items, fresh coffee and special “care packages” for the Expedition 1 crew. A few hours later, in the small hours of 3 December, Shepherd and his crewmates, Russian cosmonauts Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev, entered PMA-3 from the Unity side. “It’s kind of like Christmas up here, going through these bags!” Shepherd exulted, noting that his crew would take a coffee break as soon as they had transferred the “goodies” back to the station’s Russian Orbital Segment (ROS).

Several hours later, at 1:35 p.m. EST, the hatch into Endeavour’s payload bay opened and Tanner—designated “EV1”, the lead spacewalker, with red stripes on the legs of his Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) space suit for identification—emerged into the vacuum of space for the third time in his career. He had previously performed two EVAs during STS-82, the second Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing mission, almost four years earlier. His crewmate Noriega (“EV2”, clad in a pure-white suit) was embarking on his first spacewalk and became the first Peruvian-American to do an EVA. Manipulating the shuttle’s RMS arm from inside the cabin, Marc Garneau maneuvered the P-6 truss, like “taking your foot out of a shoe”, into position just above the Z-1 ITS and drove it down onto its installation point at shortly after 2:30 p.m. Working swiftly, Noriega drove the Capture Latch Assembly (CLA) to bring the two structures into close alignment and the spacewalkers tightened what Tanner described as “fairly good-sized bolts” onto the truss segment’s four corners, after which Garneau detached and withdrew the robotic arm.

In the words of Brent Jett, the physical installation of P-6 led to “a little shift” inside the cabin, as roles changed. During the installation, Jett choreographed Tanner and Noriega’s actions as the Intravehicular (IV) crewman, whilst Garneau handled the RMS and STS-97 Pilot Mike “Bloomer” Bloomfield provided support and visual cues with the Canadian-built Space Vision System (SVS). After installation, Garneau took Jett’s IV role and Bloomfield took over RMS operations. “He’s been training as the backup EVA crew member on the flight,” Jett said of Garneau, “so it makes sense for him to direct the EVA, because he is much more familiar with it than I am. Bloomer, at that point, takes over the arm. He’s been trained as the backup arm operator, so now during the EVA he will actually be primary for any type of interaction with the EVA crew members, and there’s quite a bit.”

Bloomfield’s first action was to manuever Noriega into position to connect nine power, command and data cables. As Noriega worked, a free-floating Tanner released a series of eight zenith and nadir bolts on P-6’s twin Solar Array Blanket Boxes (SABBs) and set them in a ready-to-deploy configuration. Each SABB measured 15 feet (4.5 meters) long and just 20 inches (51 cm) thick. Noriega then released retention bolts on the starboard array’s Beta Gimbal Assembly (BGA) launch restraint, and Tanner did likewise for its port-side counterpart, before the pair released pip-pins and rotated the SABBs from their launch positions to their deployment positions. Computer commands issued by Jett from inside Endeavour’s cabin to release the pins proved unsuccessful on the first attempt, but the second effort went smoothly and the starboard SAW was successfully deployed. The continuous process took 13 minutes to complete and was beyond Jett’s view, although a camera in Endeavour’s payload bay provided him with visual cues.

“We get sort of the lucky part…our participation actually comes to sending the command for the deployment,” said Jett before the flight. “The reason for that is because we’re moving a mechanical system, while it’s deploying, so in case it needs to be stopped, ideally you would want somebody who can actually see what’s happening, rather than someone issuing commands in the blind.” From his perspective, it struck Jett as a little unfair; an honor that should have been handed to Shepherd and the Expedition 1 crew to deploy the latest component of “their” space station. “But unfortunately, they just have no way of seeing it while it happens,” said Jett. “It’s a big moment. I think Carlos really wanted to be the one to send the command. He’s been following this hardware for a really, really long time, but if he’s outside, then that’ll fall to me.”

However, one pin on the port-side SABB remained in its closed position. In the meantime, Tanner and Noriega concluded their first EVA, returning inside Endeavour’s airlock at 9:08 p.m. EST, after seven hours and 33 minutes; the tenth-longest spacewalk in history at that time. It also marked the first use of the new Wireless Video System (WVS) and small suit-mounted television cameras, with wide-angle lenses, which provided impressive bird’s eye views of the spacewalkers at work. “We call them the Joecam and the Carloscam,” Tanner joked before the mission. “You’ll be able to see exactly what we’re seeing. This is going to be real thrilling. It’s a tremendous EVA tool.”

Shortly after the end of EVA-1, Jett again commanded the SABB pins to close, then re-open. At 9:20 p.m. EST, confirmation was received that all pins had successfully disengaged, but Mission Control elected to wait before deploying the port-side SAW, in order to verify that its starboard counterpart had tensioned properly. Over the following few hours, imagery would reveal that—although the array successfully began to generate power to the batteries—there appeared to be some slack in its support wires, raising concerns about its stability during shuttle dockings and orbital maneuvers. In the meantime, P-6’s forward Photovoltaic Radiators (PVRs) was unfurled without incident to begin the process of dissipating waste heat from its on-board electronics.

Next day, 4 December, the port-side array was deployed in a multi-step fashion, with the process halted at several points in order to allow motion in the solar array blankets to dampen out and to shake loose two rows of “sticky” panels. As a result, it took almost two hours to complete, far longer than the 13 minutes needed to unfurl the starboard array, but when fully extended it brought the tip-to-tip length of the two SAWs and their associated equipment to 240 feet (73.1 meters), creating an electrical potential of close to 64 kilowatts from more than 65,000 solar cells.

The STS-97 crew had deployed the largest set of solar arrays ever assembled in space and the stage was set, on 5 December, for Tanner and Noriega’s second EVA. Fittingly, it was the University of Southern California’s fight song, Fight On—played for graduate Noriega—which awakened the astronauts from their slumbers, early that morning, and the five men immediately pressed into their spacewalk preparations. In contrast to the first EVA, Noriega was first out of the airlock, setting up safety tethers, and both spacewalkers were in the floodlit payload bay by 12:21 p.m. EST. Their primary task was hooking up power and data cables and connecting ammonia coolant lines, but began their activity by inspecting the starboard SAW to better understand the condition of the tensioning system. Working together, they moved an S-band Antenna Subassembly (SASA) from the starboard face of the Z-1 truss to the top of P-6, removed thermal shrouds from a DC-to-DC Conversion Unit (DDCU) and the Baseband Signal Processor (BSP) and released cinches on the aft PVR. The second EVA ended after six hours and 37 minutes.

Early on 6 December, the crew awakened to news that another task was being added to their third EVA. “Station and shuttle managers sent up plans for adjusting the tension levels on the solar blankets on the starboard solar array,” NASA reported. “The plan calls for the shuttle crew to retract the array’s mast 2-3 feet (60-90 cm) to generate some slack in the tension cables. Noriega will pull the slack through ewach spring-loaded take-up reel, then Tanner will manually “wind” the tension reels. When each has reached its limit, Tanner will let it unwind by spring force, while Noriega guides the cable onto the reel grooves. The outboard reel will be first, followed by the inboard reel.”

Described by NASA as “added warranty work”, the effort got underway at 11:13 a.m. EST on 7 December, about 35 minutes ahead of schedule, and the spacewalkers moved to the top of the P-6 truss, as Jett, Bloomfield and Garneau oversaw the slight retraction of the starboard mast. Their work progressed with such exceptional smoothness that Tanner and Noriega were assigned a couple of “get-ahead” tasks, preparatory to the arrival of the U.S. Destiny laboratory aboard shuttle Atlantis on STS-98, then planned for a January 2001 launch. The two men even “topped-off” the P-6 truss with an image of an evergreen tree. The idea had come up in pre-flight discussions between Tanner and Noriega. “It was in keeping with the tradition of steel-workers, who, when they build a tall structure, put a tree on top,” said Noriega in a Smithsonian interview. “You can find different accounts of where the tradition began and why they do it, but it’s supposed to bring good luck to the building.”

The decision to affix the image of the evergreen tree came late in their STS-97 training, after the addition of a task to install a Floating Potential Probe (FPP)—tasked with monitoring the electrical potential of plasma around the space station—near the top of P-6. As the bag for the hardware was being fabricated, Tanner and Noriega asked the designers for a silhouette of the tree to be sneaked inside. “They gave us a strange look,” continued Noriega, “but when we explained why we wanted it, all of a sudden you could see them brighten up.” They also ensured that it was a personal effort, for STS-97’s Flight Director had previously worked on a construction site and Tanner and Noriega also sought the input of technicians and engineers who had bent the steel to build the P-6 truss itself.

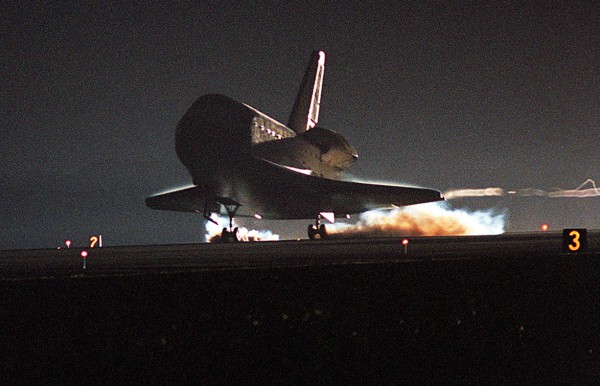

The third and final EVA concluded at 4:23 p.m., after slightly more than five hours, bringing STS-97’s total to 19 hours and 20 minutes. Shortly thereafter, Endeavour’s cabin pressure was returned to its normal 14.7 and at 8:38 a.m. EST on 8 December, the last hatches between the shuttle and the ISS were opened and the STS-97 and Expedition 1 crews exchanged handshakes in orbit for the first time. The eight spacefarers held a news conference, but their time together was brief—a little more than 24 hours—for the hatches were closed at 10:51 a.m. on the 9th and Endeavour undocked at 2:13 p.m., after almost seven full days linked to the station. After Jett had maneuvered his ship away, Bloomfield took the controls for an hour-long flyaround inspection of the orbital outpost. Two days later, at 6:03 p.m. EST on 11 December, about 36 minutes after local sunset, Endeavour alighted on Runway 15 of the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), wrapping up a flight of just shy of 11 full days.

Their legacy was the brightest artificial structure in Earth’s skies. “Nothing like this has ever been done,” said Marc Garneau before the flight. “The station will look tremendous. It’ll be visible from the ground as a very bright object in the night sky.” Added Joe Tanner: “These things are huge. Once the arrays are out, the station becomes the third-brightest star in the heavens”. Aside from being visually impressive, the P-6 truss provided the necessary early electrical and cooling capability for the completion of Phase 2 of ISS construction—the powering-up of the Unity node and the installation of the Destiny laboratory, the Canadarm2 robotic arm and the Quest airlock—before efforts got underway to build out the remainder of the ITS and install further truss segments and three more sets of SAWs. At length, in October 2007, P-6 was detached from its temporary place atop the Z-1 truss and installed at its permanent position at the furthest-outboard point on the port-side of the ITS. It has experienced troubles over the years, including ammonia coolant leaks, which were tended and a Trailing Thermal Control Radiator (TTCR) deployed during U.S. EVAs in November 2012 and May 2013, before P-6 was reconfigured to its original state during U.S. EVA-33 on 6 November 2015.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 25th anniversary of ASTRO-1, a shuttle mission whose launch was repeatedly frustrated by the loss of Challenger and a summer of fuel leaks.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Hi there, all is going sound here and ofcourse every one is sharing facts, that’s truly

good, keep up writing.