At the cusp of nightfall on 5 December 2001, Space Shuttle Endeavour dispelled some of the darkness which had cloaked the world for several months. Less than 12 weeks since the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States—and characterized by a heightened sense of security at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida—STS-108 was the first U.S. piloted space mission since an event which cost almost 3,000 innocent lives. As detailed in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, Endeavour’s crew rocketed into orbit with a hefty payload of science and supplies for the International Space Station (ISS), together with a poignant cargo of New York City police patches and badges, a New York Fire Department flag, and almost 6,000 small U.S. flags in honor of the victims and their families.

Reaching orbit just 8.5 minutes after departing Pad 39B, Endeavour’s crew quickly set to work configuring the shuttle from a launch vehicle into an orbital spacecraft, ahead of docking at the space station on 7 December. During their first day aloft, the seven-strong crew—Commander Dom Gorie, Pilot Mark Kelly, and Mission Specialists Linda Godwin and Dan Tani, together with the Expedition 4 space station increment of Commander Yuri Onufrienko and Flight Engineers Carl Walz and Dan Bursch—activated the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm, checked out the shuttle’s docking mechanism, and prepared their space suits for an extensive array of robotics and EVA work. Meanwhile, Gorie and Kelly executed a series of rendezvous maneuvers to reach the station.

“To get to fly formation with a spaceship,” said Gorie, before the flight, “bringing together the two most technologically advanced vehicles our country has ever produced, and getting to mate them together, is a pilot’s dream come true.” As Gorie flew the orbiter from the aft flight deck, Kelly oversaw rendezvous computers from the Commander’s seat, Tani handled the rendezvous checklist, and Godwin used a hand-held laser rangefinder to measure distances and velocities. Shortly after midday EST on the 7th, Gorie assumed manual control of the shuttle, about a half-mile (0.8 km) “beneath” the ISS. He closed to about 600 feet (180 meters), then maneuvered a quarter-circle around the station, before closing in on Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2, at the forward end of the U.S. Destiny lab.

Docking occurred at 3:03 p.m. EST, high above England. Minor difficulties were encountered when Endeavour’s docking ring and the station’s own docking mechanism briefly refused to align correctly, but this issue was soon corrected and hatches were opened at 5:42 p.m. The incoming crew was welcomed by the resident Expedition 3 increment of Commander Frank Culbertson and Flight Engineers Vladimir Dezhurov and Mikhail Tyurin, who had been aboard the ISS since the first half of August.

Ahead lay a week of joint activities, including the transfer of authority between Culbertson and his Expedition 4 counterpart, Onufrienko. Early on 8 December, the first primary objective of STS-108 got underway, when Mark Kelly and Linda Godwin worked together to remove the Italian-built Raffaello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) from Endeavour’s payload bay and mate it to the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the station’s Unity node. With Godwin at the RMS controls, the 21-foot-long (6.4-meter) cylindrical module was lifted from its berth aboard the shuttle at 12:01 p.m. EST and secured in place on the space station less than an hour later, at 12:55 p.m. Aboard the module were about 6,000 pounds (2,700 kg) of equipment, crew supplies, and scientific payloads, including eight Resupply Stowage Racks (RSRs) and four Resupply Stowage Platforms (RSPs) to augment existing ISS systems and the station’s spare parts inventory.

Later that evening, the STS-108 crew set to work unloading Raffaello, which was making its second orbital mission, after a debut in April 2001. Unpacking the MPLM offered time for a spot of banter, as the crew apparently unpacked a folded-up Dan Bursch from one of the large containers. They used barcode readers to log items. “The problem with Dan,” explained Tani, “was that we couldn’t find his barcode, but after a lot of searching—fortunately, not too much searching—we found it and checked him off the list!”

Meanwhile, the incoming Expedition 4 crew installed their seat liners in the Soyuz TM-33 spacecraft, which they would henceforth use in the event of an emergency departure from the ISS. At the same time, the outgoing Expedition 3 crew transferred over to Endeavour to become members of the STS-108 crew for the return home. Crew transfer operations was completed by 5 p.m. EST on 8 December.

Awakened on the morning of the 9th to the patriotic sound of “It’s A Grand Ole’ Flag,” performed by the Fire Department of New York Emerald Society Pipes & Drums, the crews set aside some time to remember the victims of 9/11, almost three months to the day since the atrocities. Before launch, Kelly had visited the World Trade Center site with then-NASA Administrator Dan Goldin. The event drew harrowing comments from Gorie and Culbertson. The latter was the only American citizen in space on 9/11 and remembered the “disturbing sight” of seeing his homeland under attack. In addition to thousands of small flags, Endeavour carried a larger U.S. flag which had been retrieved from the ruins of the World Trade Center. “It is a tremendous symbol of our country,” said Gorie. “Just like our country, it was a little battered and bruised and torn, but with a little bit of repair it is going to fly as high and as beautiful as it ever did.”

Although the Quest airlock was in place on the station by the time of STS-108, plans had already been set for Godwin and Tani to execute their EVA out of the shuttle’s airlock. This required hatches between Endeavour and the ISS to be closed at 7:43 p.m. EST on 9 December, in order that the shuttle’s cabin pressure could be reduced from its normal 14.7 psi down to 10.2 psi. This allowed the spacewalkers to better protect their bodies from decompression sickness as they moved into the low-pressure, pure-oxygen environment of their space suits. Godwin and Tani were tasked to install protective thermal blankets around the Bearing, Motor and Roll Ring Module (BMRRM) on the port-side solar array of the station’s P-6 truss.

The BMRRMs form part of the bearing gimbal assembly at the base of each array, both “driving” and passing primary power from the solar “wings” to the rest of the station, in addition to offering structural support. Since its installation in December 2000, the motor used by the port-side P-6 array exhibited higher than normal currents, suggestive of something causing it to bind or “hang up.” By the fall of 2001, the issue had become so severe that the port-side array could no longer be used to track the Sun, thereby potentially limiting the ISS power supply. Plans were already afoot for Godwin and Tani to remove and replace the BMRRM, but subsequent analysis allowed managers to opt for installing thermal blankets around two barrel-shaped Beta Gimbal Assemblies (BGAs) at the base of the solar arrays. The BGAs controlled the rotation of the arrays and, it was hoped, the blankets would reduce temperature extremes and solve the motor problems. If Godwin and Tani’s efforts failed to solve the issue, a full-up BMRRM replacement EVA would be manifested on a subsequent mission.

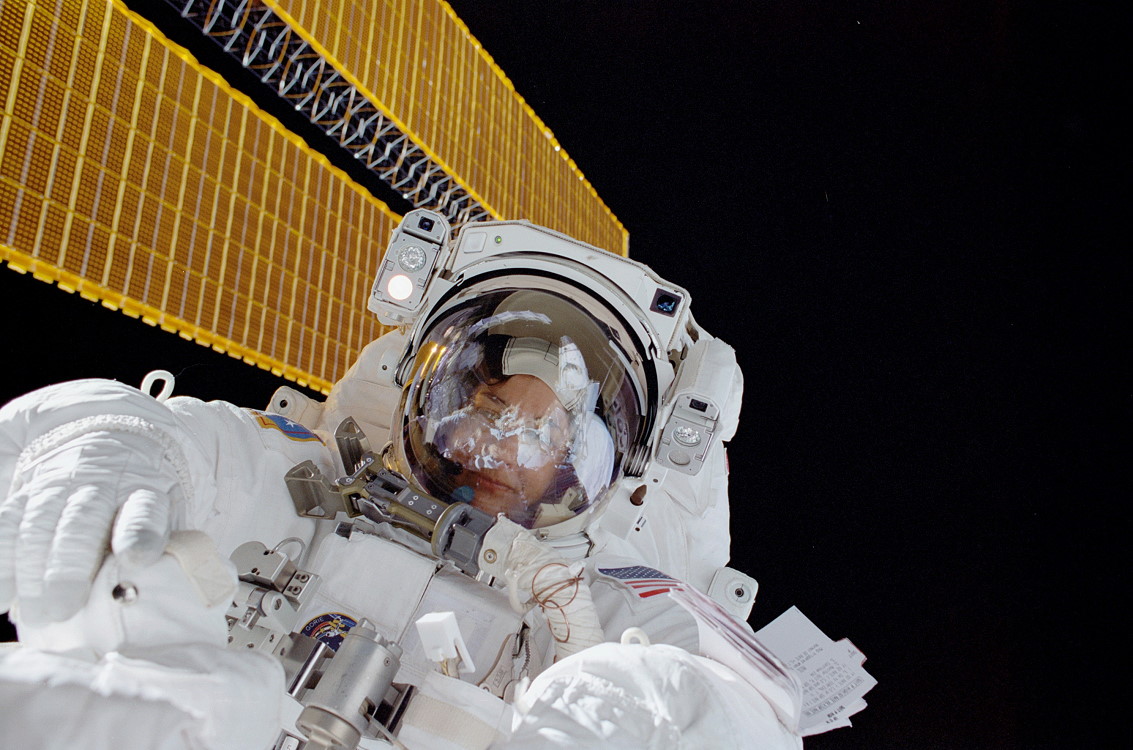

The EVA got underway at 12:52 p.m. EST, with Godwin first to poke her head out of the shuttle’s airlock and into the floodlit payload bay. Hundreds of miles “below,” she was presented with the glorious sight of the Pacific Ocean and the coastline of South America. She also later paid tribute to their space suits. “We got out with such confidence in these suits that we don’t really think about … that we’re in our own little spaceship,” she recalled later, “where everything has to work just right.” Quickly joined by Tani, the duo were transported halfway up the P-6 truss on the shuttle’s RMS, manipulated by Kelly. They reached the work site, a dizzying 80 feet (24 meters) above the payload bay, and successfully wrapped the insulation blankets around the two BGAs.

Having completed their primary task, Godwin and Tani moved on to secure one of four legs bracing the starboard P-6 array. However, they were unable to close the latch, although NASA noted that the other three legs were sufficient. Performing his first EVA, Tani later expressed amazement at the speed of the transition from orbital daytime to darkness; so fast, in fact, that he and Godwin had to consciously remind one another to switch their helmet lights on and off.

Wrapping up their EVA after four hours and 12 minutes, Godwin and Tani bookended 2001 as a record year in terms of spacewalking. No fewer than 18 EVAs had been completed, including three to install the U.S. Destiny lab in February, two more to deliver Canadarm2 in April and three others to outfit the Quest airlock in July. This achievement doubled the previous record of nine EVAs, jointly achieved aboard America’s Skylab space station in 1973 and, more recently, in 1997 aboard Mir and the shuttle. Following their return inside the station, Godwin and Tani joined their crewmates for a joint meal of U.S. and Russian food in the Zvezda service module. Their meal was concluded with an impromptu musical soiree, with Walz on the keyboard and Gorie on guitar.

Logistics and resupply were the main focus for the remainder of the STS-108 crew’s time on the station and Culbertson ceremonially relinquished command to Onufrienko. At 8:46 a.m. EST, exactly three months to the moment since the first airliner ploughed into the World Trade Center, the astronauts and cosmonauts fell silent and listened to the sound of their respective national anthems. “In stark contrast to the international co-operation and unity in our effort to take mankind literally to the stars,” STS-108 Lead Flight Director Wayne Hale told them, “we are reminded of our loss and sorrow, due to the acts of violence and terror in an unprecedented attack on freedom, democracy and civilization itself.” He observed that almost 3,000 individuals, many of them from member-nations of the ISS Program, had perished on that dreadful Tuesday morning.

Endeavour’s stay at the space station was extended by 24 hours, allowing the STS-108 crew to provide additional maintenance support, including work on a treadmill and a faulty compressor in an air-conditioning unit in the Zvezda service module of the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS). Broken treadmill parts were among the cargo to be returned home aboard the MPLM. By mid-afternoon on 14 December, Kelly and Godwin set to work detaching Raffaello from Unity nadir, using Endeavour’s RMS arm. The Italian module was safely back on its berth in the shuttle’s payload bay by 5:44 p.m. EST.

Next morning, the 15th, Gorie smoothly undocked from the station at 12:28 p.m. EST, as the two spacecraft flew above the Indian Ocean, just off the coast of Australia. Moving away, Kelly assumed manual control from the aft flight deck and executed a half-circle maneuver, before commencing the departure from the ISS. One of the final objectives of STS-108 was the deployment of a small satellite called the Student-Tracked Atmospheric Research Satellite for Heuristic International Networking Experiment (STARSHINE)-2, which Tani ejected from a Getaway Special (GAS) canister in Endeavour’s payload bay at 10 a.m. EST on 16 December. Weighing 85 pounds (38.5 kg), the spherical satellite measured about 19 inches (48 cm) in diameter and carried hundreds of aluminum mirrors and 31 laser retroreflectors. It was flown as part of a project involving 30,000 students from 26 nations, who carefully observed its position and orbital decay characteristics as part of ongoing efforts to better understand Earth’s upper atmosphere.

Despite a problem with one of Endeavour’s Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), the shuttle was sailing through her 17th space mission in excellent shape. Following customary flight control systems checks—and with the returning Expedition 3 crew played Bing Crosby’s “I’ll Be Home For Christmas” as one of their wake-up calls—the weather in Florida was deemed perfect for a landing on the first of two opportunities on 17 December. Gorie fired Endeavour’s Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines for the irreversible deorbit “burn” at 11:50 a.m. EST. An hour later, wrapping up a 4.8-million-mile (7.7 million km) journey, the shuttle headed directly for Runway 15.

As they approached the Florida spaceport, they were momentarily dismayed by the accumulation of clouds over the landing site. Finally breaking through the cloud deck at 5,500 feet (1,670 meters), whilst traveling at 345 mph (555 km/h), they spotted the runway, dead ahead. Kelly pressed the button to deploy Endeavour’s landing gear at an altitude of about 300 feet (90 meters) and all six wheels were down and locked into position by 200 feet (60 meters). Touchdown occurred at 12:55 p.m. EST, with the main gear hitting the runway at 230 mph (370 km/h) and Endeavour rolled smoothly to a halt.

But for Mark Kelly’s young daughter, Claire, who had watched the launch and followed STS-108 on television, there was one part of the mission which incomparably surpassed the rest. It was not Endeavour’s roaring ascent into orbit, nor the sight of the orbiter’s wheels kissing the concrete runway at mission’s end. Rather, Claire’s “best bit” was the sight of her father deploying the shuttle’s drag chute to bring himself and his six crewmates safely to a stop after a dramatic and eventful stay in space.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 10th anniversary of STS-116, which saw a record-breaking four spacewalks performed by a single astronaut on a single mission and set the stage for significant expansion of the International Space Station (ISS).

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace