A quarter-century ago, today, six astronauts began an ambitious mission which put virtually all of the Space Shuttle’s capabilities—satellite deployment and retrieval, rendezvous and proximity operations, research and Extravehicular Activity (EVA)—to the test, as well as providing a great insight into the work that NASA would require to build the International Space Station (ISS).

STS-72, launched aboard Endeavour on 11 January 1996, was tasked with capturing a Japanese spacecraft after ten months in orbit, as well as deploying and retrieving a small free-flying satellite and evaluating tools for the assembly and maintenance of the International Space Station (ISS).

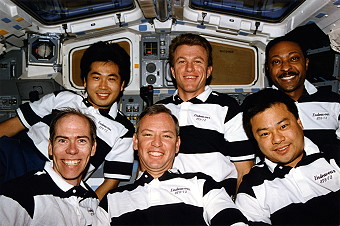

Commander Brian Duffy, Pilot Brent Jett and Mission Specialists Leroy Chiao, Winston Scott, Dan Barry and Japan’s Koichi Wakata—were tasked with the retrieval of the Japanese Space Flyer Unit (SFU) satellite from low-Earth orbit.

The octagonal-shaped payload had been launched atop a H-II rocket ten months earlier, laden with autonomous experiments in materials science, biology, engineering and astronomy. Achieving a rendezvous with the SFU on the third day of STS-72 required Endeavour and her crew to launch within a 49.5-minute “window” extending from 4:18 a.m. EST through 5:07 a.m. EST on 11 January.

The astronauts boarded the orbiter without incident that morning and, despite a couple of minor technical issues—slightly cooler-than-normal main engines and communications glitches—Endeavour speared into the night sky at 4:41 a.m. EST.

At the point of orbital insertion, Duffy and his men trailed the SFU by 9,160 miles (14,740 km), closing this distance by up to about 860 miles (1,390 km) during each circuit of Earth, and the crew spent their first day in space checking out their rendezvous tools and equipment.

With Wakata designated as the primary operator of the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS), he was responsible for powering up and testing the Canadian-built mechanical arm, whilst Duffy carried out tests of controls on the aft flight deck. By the evening of 11 January, halfway through the first day of the mission, Endeavour had continued to reduce the distance between herself and the SFU. The Japanese flight controllers verified that their satellite was in good shape, despite having lost functionality in two reaction-control thrusters, which were not considered a threat to the retrieval.

Early on the 12th, Duffy and Jett pulsed the shuttle’s Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters to slightly adjust their orbit and avoid an unwanted close encounter with the U.S. Air Force’s MISTY military satellite. Had they not taken the action, it was estimated that Endeavour would have passed within an uncomfortably close 0.7 miles (1.2 km) of the dead satellite. As circumstances transpired, the two spacecraft passed within 5 miles (8 km) of each other. By that evening, the shuttle was just 300 miles (480 km) behind the SFU, closing at a slower rate of about 60 miles (96 km) per orbit.

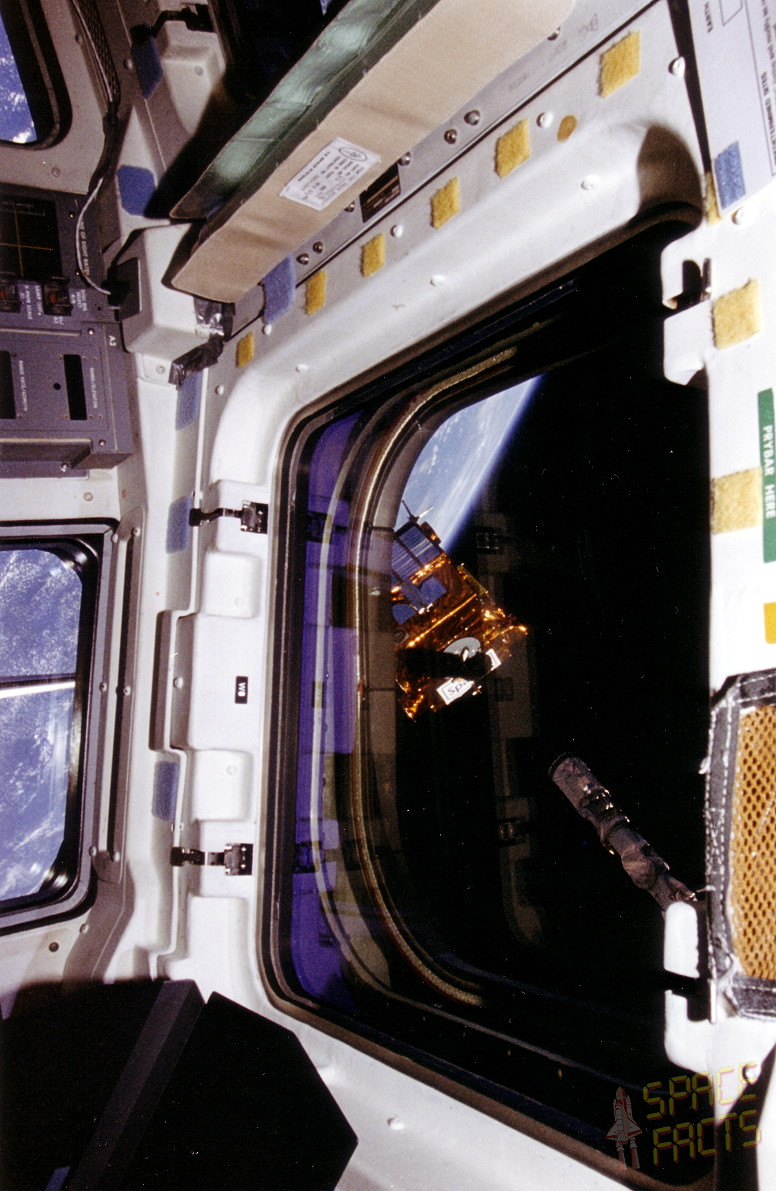

The final rendezvous in the early hours of 13 January began about three hours ahead of the scheduled retrieval, with a Terminal Initiation (TI) burn of Endeavour’s RCS thrusters, at which stage she was about 9.1 miles (14.8 km) from her quarry. The shuttle approached the SFU along the so-called “R-Bar” corridor, tracing an imaginary line directly “upwards” from the centre of Earth to reach the SFU. At this stage, Wakata powered up the RMS and extended it high above the payload bay, ready to capture the satellite.

As they drew to within about a half-mile (0.8 km) of each other, about 90 minutes ahead of the scheduled 4:26 a.m. EST retrieval, the shuttle’s rendezvous radar locked onto the SFU. With a constant stream of range and rate-of-closure data at his disposal, Duffy assumed manual control of the orbiter.

Drawing nearer, at 590 feet (180 meters), he switched the shuttle’s RCS to “Low-Z” mode, which employed offset thrusters in the nose and tail for braking, rather than risking contamination by using the thrusters facing directly toward the satellite. During this period, range and rate-of-closure data was provided by Chiao, courtesy of a hand-held laser ranging device. By the time Endeavour reached about 147 feet (45 meters) from the SFU, he entered a 45-minute station-keeping phase as the Japanese flight controllers began to command the satellite’s twin solar arrays to close and latch into place.

It was during these activities that STS-72’s first gremlin reared its head. The satellite had earlier been placed onto internal battery power, ahead of the commands for it to close its solar arrays. Although they retracted correctly, they did not properly latch into place. As a result, it was decided to discard both array canisters. As Endeavour and the SFU orbited high above Africa, the canisters were jettisoned to ensure that they did not complicate the retrieval.

With the two spacecraft now high above the Gulf of Mexico, near the western tip of Cuba, Wakata grappled the SFU at 5:57 a.m. EST, about 91 minutes later than planned. He then lowered it gently into the payload bay, locking it into place at 6:39 a.m. EST by closing four retention latches. The internal batteries were bypassed and a remotely-operated electrical cable was connected to the side of the satellite.

In addition to retrieving a Japanese satellite, STS-72 featured a multitude of scientific and technological payloads, including a deployable Spartan free-flyer equipped with experiments for NASA’s Office of Aeronautics and Space Technology (OAST). Designated “OAST-Flyer,” its deployment came early on 14 January. Following a thorough systems check, latches holding it in the payload bay were released and Wakata grappled OAST-Flyer with the RMS arm and released it for two days of autonomous activities.

Over those two days, Endeavour maintained a distance of about 100 miles (160 km) from OAST-Flyer, before the crew re-rendezvoused with it on 16 January, grappled it and returned it to the payload bay.

Before and after the OAST-Flyer retrieval, two spacewalks took place: the first early on 15 January, featuring Chiao and Barry, and the second on 17 January, featuring Chiao and Scott. They were part of NASA’s EVA Development Flight Test (EDFT) initiative to evaluate tools and techniques ahead of the dawn of ISS construction and maintenance. When the crew was named in late 1994, it was intended that Chiao and Barry would perform both spacewalks, but as their training developed, it was decided to incorporate Scott into the plan to increase their all-round EVA expertise.

Although Chiao had flown before, and Barry and Scott were both “rookies”, none of the three men had previously performed a spacewalk. But it made sense for Chiao to serve as lead EVA crewman. However, this produced some interesting conversations with Barry. “Dan was an interesting guy,” Chiao told the NASA oral historian. “He was flying his first mission and he felt like he should have had my job. He thought he should be the lead EVA guy…and he let me know it, which set up an interesting relationship! There was a little bit of friction between Dan and me for that reason, but we worked through it.”

Chiao and Barry’s first spacewalk was an impressive experience for them both. “Getting to do spacewalks was a surreal experience,” Chiao said later, “seeing the Earth with peripheral vision involved, really feeling like the Earth was a ball. Of course, looking through the window, you know it’s a ball, but there’s something about looking through the window and then being out there with an unrestricted view that really made it feel like it was three-dimensional for the first time.” Unsurprisingly, Chiao’s heart-rate spiked as soon as the hatch opened, then returned to normal.

Over the next six hours, Chiao and Barry labored to assemble a portable work platform and evaluate tool boards, sliding locks and rigid tether sockets, as well as a Rigid Umbilical and the new Articulating Portable Foot Restraint (APFR) for station assembly tasks. They assembled the hardware onto the end of the RMS, which enabled Jett to grapple various pieces of hardware intended to hold large modular components.

Two days later, after the OAST-Flyer retrieval, Chiao and Scott were outside for the second EVA, although their departure from Endeavour’s airlock met with slight delay due to minor issues when donning their suits. On the second spacewalk of his career, interestingly, Chiao’s heart rate did not spike as it had done two days earlier. “It’s interesting how adaptable humans really are,” he said later, “and you get used to things.”

The astronauts evaluated thermal modifications to their suits, including battery-powered heating elements to warm their fingers, thermal socks and toe-caps and adjustable “mittens”. They also tested the new capability to shut off cooling water to their suits’ ventilation garments if they became too cold. “It was hardware-intensive,” Scott said later. “We had Electronic Cuff Checklists, power tools, rigid umbilicals, electrical fluid line connectors, improved helmet lights; you name it, we had it. We had stuff hanging off us everywhere. We could set off metal detectors from orbit!”

By the time Chiao and Scott returned to the airlock, STS-72’s EVA duration had reached a little more than 13 hours. In the meantime, a multitude of other experiments chugged along in the shuttle’s payload bay. Of concern were colder-than-predicted temperatures on one of SFU’s fuel lines—with an elevated risk that it might freeze and start leaking hydrazine—although Duffy maneuvered Endeavour to a slightly warmer attitude and the problem resolved itself.

In the small hours of 20 January, after nine days in orbit, the shuttle swept to a pre-dawn landing in Florida to complete the first U.S. human space mission of 1996. STS-72 had been a successful test not only of the shuttle’s myriad capabilities, but also had taken huge strides towards the ISS: a station which five of the six crewmen would go on to visit, build and inhabit later in their careers.