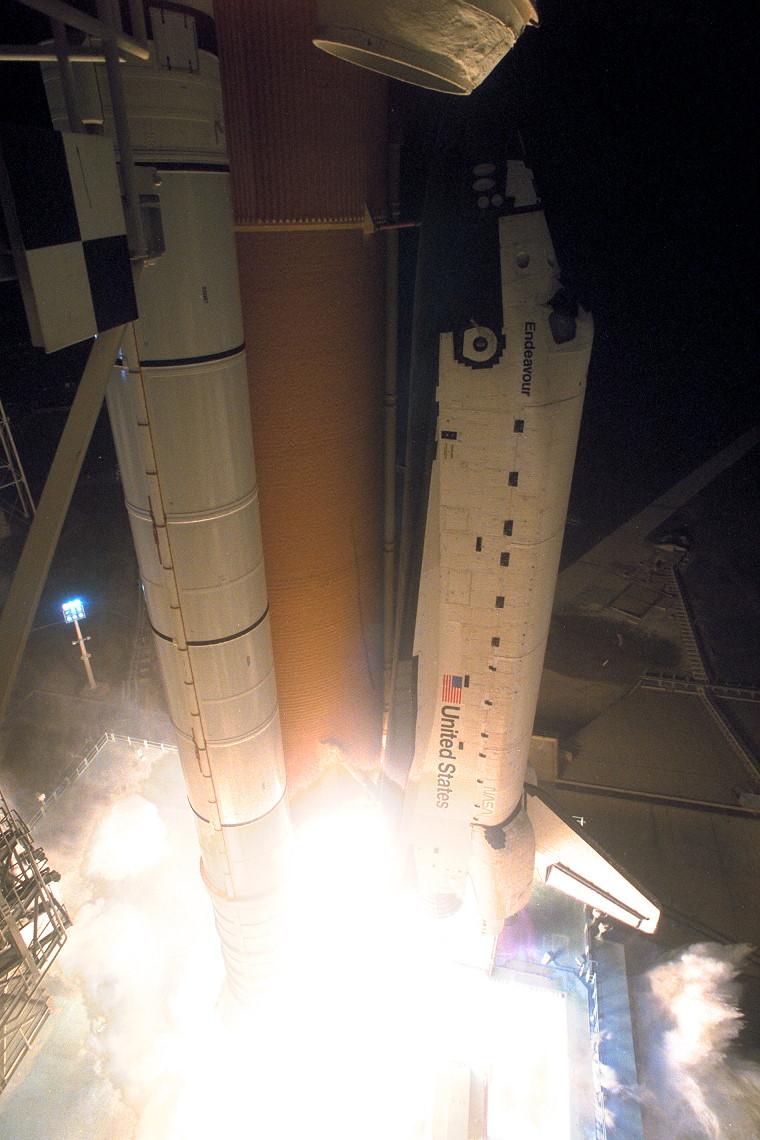

Twenty-five years ago, with a resounding “Howl for the Wolfman”, Endeavour roared into the night for the shuttle program’s eighth (and second-to-last) docking at Russia’s Mir space station. Despite only a 40-percent chance of acceptable weather on the Space Coast on the night of 22 January 1998, STS-89 Commander Terry Wilcutt and his crew stepped smartly through their pre-launch rituals, donned their pressure suits, headed to the launch pad and rocketed to orbit, right on the opening of a narrow, ten-minute-long “window”.

Wilcutt, who had flown to Mir before, was particularly pleased that his crew did not have to wake in their quarters at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida until mid-morning that Thursday, a quarter-century ago. Just before 6 p.m. EST, they departed the Operations & Checkout Building, walking out into the glare of spotlights and flashbulbs, and were securely strapped into their seats aboard Endeavour by 7:25 p.m.

A brief issue with the ground-based data-processing system forced a slight hold in STS-89’s countdown, requiring launch controllers to shorten the planned 46-minute-long hold at T-9 minutes to just 25 minutes to meet the extremely tight launch window, which opened at 9:48:15 p.m. Fortunately, the gods of good fortune were on Endeavour’s side that night, as everything came together in the final minutes.

Seated to Wilcutt’s right side in the cockpit, Pilot Joe Edwards activated the three Auxiliary Power Units (APUs) at T-5 minutes. Downstairs in the shuttle’s darkened middeck, astronaut Andy Thomas—who was heading for a 4.5-month stay on Mir—remembered hearing the APUs spinning up to speed, far below them.

In the gloom, he found the gloved hands of his STS-89 crewmates Bonnie Dunbar and Salizhan Sharipov. The trio clasped hands in a moment of crewmemberly solidarity.

Originally, the Shuttle-Mir Program envisaged seven dockings between U.S. orbiters and the Russian space station, which would deliver supplies and equipment and exchange crew members to build America’s long-duration flight experience before the advent of the International Space Station (ISS) era. But on 30 January 1996, following a summit in Washington, D.C., between U.S. Vice President Al Gore and Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, two more dockings were added to the manifest.

“The eighth and ninth Mir flights will use the Space Shuttle to reduce a significant logistics shortfall on Mir, conduct vital engineering research and expand our knowledge and experience of the effects of long-duration weightlessness,” NASA explained. “In addition, these extended Mir operations will assist Russia in its objective to extend the Mir on-orbit lifetime through Fiscal Year 1999.”

A year later, in January 1997, Andy Thomas arrived in Russia’s Star City cosmonaut training center, on the forested outskirts of Moscow, initially as backup to fellow astronaut Dave Wolf, who was nearing the midpoint of his own training flow for the last U.S. long-duration Mir stay, scheduled to begin in January 1998. Thomas was not expected to fly to Mir himself, but was instead considered a non-flying backup crewman.

“The plan was I’d stay there a year and Dave Wolf would go fly the last increment on Mir and I would come back and do something else,” Thomas later related to the NASA oral historian. “I actually undertook that mostly because I was curious about the Russian environment, not expecting that I would get a flight out of it.”

In the meantime, in March 1997 the “core” STS-89 crew was announced. Two-time shuttle veteran Wilcutt and first-timer Edwards would be joined by four-flight shuttle veteran Bonnie Dunbar and “rookies” Mike Anderson—who in February 2003 would lose his life in the STS-107 tragedy—and Jim Reilly.

And the following October, cosmonaut Salizhan Sharipov, an ethnic Uzbek, a Kyrgyz national, but a citizen of Russia, was announced as the final STS-89 crew member. But by that time, the nature of who would be riding uphill and downhill to and from Mir aboard Endeavour had changed markedly.

Astronaut Wendy Lawrence was assigned to spend four months on the station, launching aboard shuttle Atlantis on STS-86 in September 1997 and returning to Earth aboard Endeavour on STS-89 in January 1998. That would position Dave Wolf to replace her, launching to space on STS-89 and returning home on STS-91 the following June.

However, following a much-publicized series of calamities earlier in 1997—including computer failures, a fire and a collision with a Progress cargo ship—it became necessary to certify U.S. Mir crew members in the Russian Extravehicular Activity (EVA) suit to allow them to participate in spacewalks. Since Lawrence had not trained for an EVA and was too small to fit the Russian suit, her long-duration stint on Mir was taken by Wolf. And correspondingly, Wolf’s own seat on STS-89 went to Thomas.

STS-89 marked Endeavour’s return-to-flight after more than a year of maintenance. As the youngest member of NASA’s shuttle fleet, she logged 11 missions between May 1992 and May 1996, then headed to Palmdale, Calif., in July 1996 for eight months of refurbishment.

During her time on the West Coast, Endeavour received 63 upgrades, including the transfer of her airlock from its “internal” perch in the middeck to a new “external” position in her payload bay and the addition of an Orbiter Docking System (ODS) for Mir and ISS operations. At the same time, her Extended Duration Orbiter (EDO) capability was removed and her Thermal Protection System (TPS) received significant attention.

Returned to the East Coast at the end of March 1997, Endeavour was put directly back into pre-launch processing for STS-89. And on her 12th orbital voyage, she became the first in the fleet to boast three upgraded Block IIA main engines, part of an interim effort as technical difficulties were worked in certifying Pratt & Whitney’s high-pressure fuel turbopump before the introduction of the next-generation, $1 billion Block II engine.

Six seconds before liftoff on 22 January 1998, those three Block IIA engines came alive with a thunderous rumble. From his seat, Edwards reported that all were running at full power. At T-0, the twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) ignited and STS-89 speared into the dark Florida sky.

Although the middeck had no large windows, it made little difference. “You did not need a window,” Thomas later quipped, “to know what was happening!”

Nine minutes after launch, Endeavour settled smoothly into orbit. And over the next two days, Wilcutt and Edwards gradually narrowed the distance between themselves and Mir. By the morning of 24 January, the two spacecraft were about 190 miles (310 kilometers) apart, closing rapidly, until Mir appeared as a bright glint of light in the distance.

“After sunset, it became as a star,” Sharipov remembered. “It’s unforgettable. It’s so beautiful, I’ll never forget this view.”

The view from Mir was equally impressive. “It was a real pleasure watching you guys come out of the sky,” Wolf said later. And Wilcutt’s docking at 3:14 p.m. EST was so smooth that the Mir crew—Wolf and a pair of Russian cosmonauts, Anatoli Solovyov and Pavel Vinogradov—hardly felt the moment of impact.

After four months in space, Wolf was overjoyed to see Endeavour and waved heartily from Mir’s windows during the final approach. After docking, Dunbar joked that Thomas had forgotten his suitcases and they would have to take him back.

But Wolf was having none of it. His four months had passed neither too quickly, nor too slowly. Before launching the previous September, he had mentally prepared himself for the switch.

“That was my tool for lasting the time and someday I’ll move back to Earth,” he said later. “I didn’t feel like I was moving back to Earth until the shuttle launched to come get me.”

The excitement was acute for Dunbar, too, who had trained with Solovyov for a long-duration Mir stay several years earlier. At one point, Solovyov and Vinogradov even kidded Mission Control that Dunbar was undecided about whether to return on STS-89 or not.

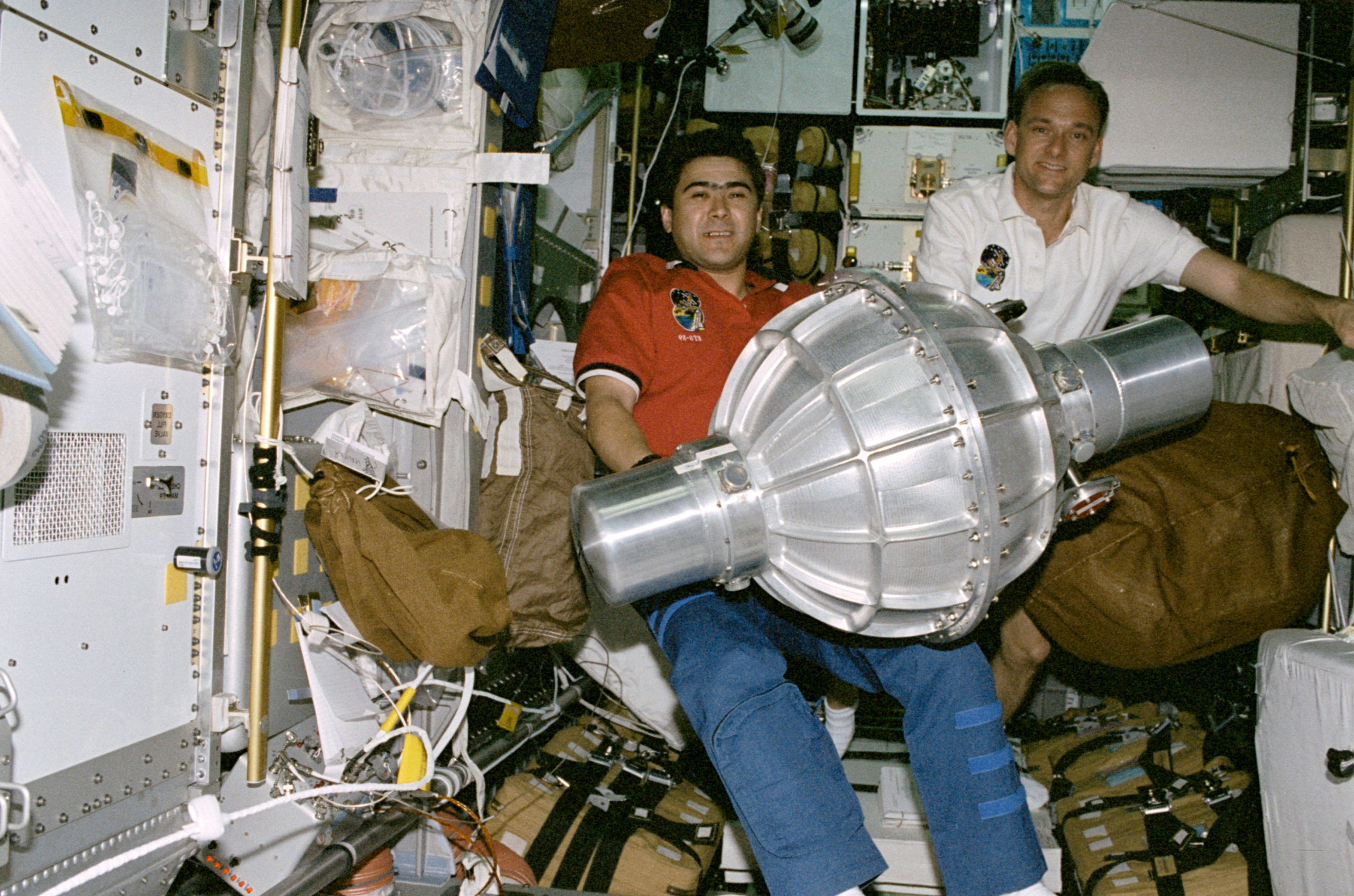

Hugs and laughter were shared, as Endeavour’s crew began offloading cargo, included fresh oranges, chocolates shaped like shuttles, new notebooks, ink pens, five large bags of drinking water and Swiss army knives. Research payloads included a habitat for swordtail guppy fish and snails, a plant nutrient facility and an experiment to understand the behavior of sands and salts at low confining pressures.

And with the exception of an erroneous reading of a thruster leak, Endeavour performed beautifully on her 12th flight. After five days docked to Mir, the crews exchanged farewell wishes and went their separate ways, with Thomas joining Solovyov and Vinogradov and Wolf joining Wilcutt’s STS-89 crew.

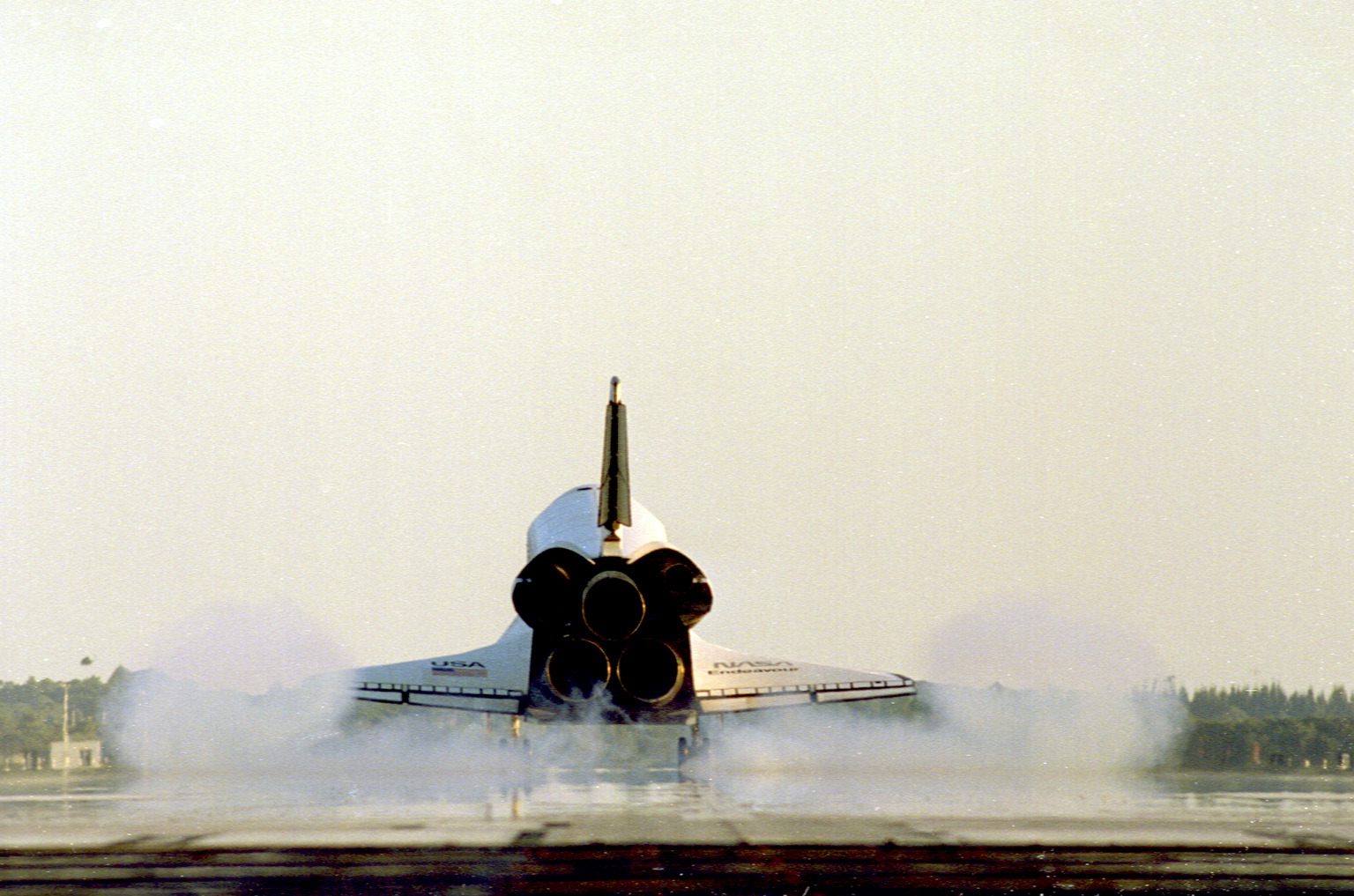

Endeavour landed safely on Runway 15 at KSC at 5:35 p.m. EST on 31 January, wrapping up a mission of slightly under nine days. And for Wolf, returning to terra firma and the sweet smell of Earth after 128 days, the experience was exhilarating.

“There’s a knock at the door and the hatch handle’s turning,” one of the middeck crew remarked as ground personnel began cranking open Endeavour’s hatch.

“I’m pretty excited about this,” came Wolf’s reply. “And the hatch is open! Oh, the smell…and the air from the Earth!”

A well-known “party animal”, Wolf joked about wanting a hot pepperoni pizza, a few drinks and a beach party, right after landing. But after agreeing to be stretchered off the shuttle for medical data collection, he decided that discretion was the better part of valor and opted against an immediate party. That would have to wait.

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:“Why I Wasn’t Devastated”: Remembering the Shuttle’s Last Visit to Mir, 25 Years On - AmericaSpace