With Sunday’s pre-dawn splashdown of Dragon Resilience after 167 days in orbit, the United States wrapped up not only its first “operational” Commercial Crew rotation mission to the International Space Station (ISS), but also the first oceanic return of the astronaut crew in the hours of darkness in more than half a century. Following almost six months spent living and working aboard the sprawling orbital outpost, Crew-1 Commander Mike Hopkins, Pilot Victor Glover and Mission Specialists Shannon Walker and Soichi Noguchi completed a smooth hypersonic descent through the atmosphere and a parachute-assisted landing in the Gulf of Mexico, to the south of Panama City, Fla., at 2:56 a.m. EDT.

Between them, they set a raft of impressive records, including the on-orbit swearing-in of the first U.S. Space Force astronaut, the most experienced African-American astronaut, the shortest-tenured ISS Commander and the most experienced Japanese spacewalker.

Dragon Resilience—which on 7 February secured a record for the longest voyage by a U.S. crewed orbital vehicle, when it eclipsed the 84-day achievement of Skylab 4 in early 1974—undocked from the space-facing (or “zenith”) port of the station’s Harmony node at 8:35 p.m. Saturday, a pair of “burns” by her Draco thrusters establishing an initial separation distance.

With splashdown in the Gulf of Mexico targeted for 6.5 hours later, efforts to ready the ship for its return to Earth entered high gear in the final hour. Crew Dragon’s unpressurized “trunk” was jettisoned, after which the spacecraft was wholly reliant upon its internal batteries, and the 16-minute-long “deorbit burn” was declared complete at 2:20 a.m. Shortly afterwards, Dragon Resilience’s nose cone was closed for re-entry.

At 2:35 a.m., Hopkins, Glover, Walker and Noguchi were instructed to close their helmet visors, ahead of “Entry Interface” and a projected seven-minute-long period of radio blackout which began at 2:43 a.m. The astronauts pulled an estimated 3-5 times the force of terrestrial gravity during this critical timeframe.

Passing through peak atmospheric thermal duress, the spacecraft’s drogue parachutes were deployed at an altitude of 18,000 feet (5,500 meters) above the Gulf of Mexico. And a minute or so later, Crew Dragon’s four red-and-white main parachutes were unfurled, slowing the craft from 120 mph (190 km/h) to a mere 16 mph (28 km/h) at the point of water impact.

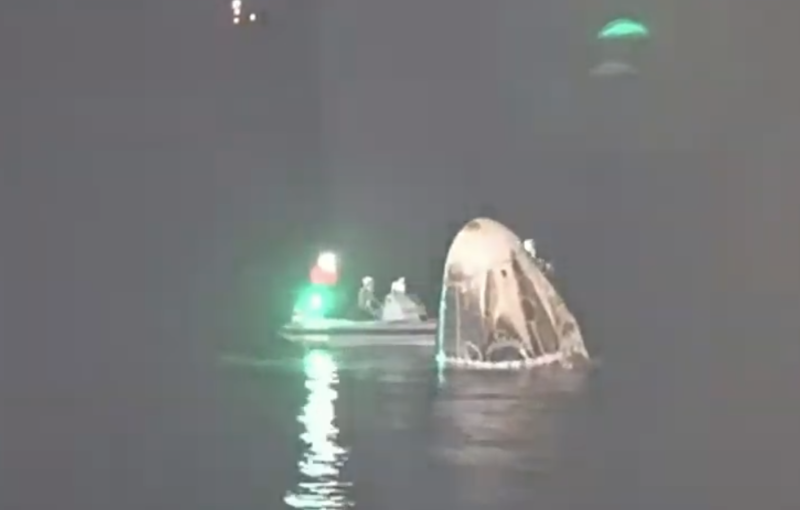

As the SpaceX recovery vessel “Go Navigator” stood by, and a pair of fast boats approached the bobbing spacecraft to install hoisting equipment and sniff for any possibility of leaking hypergolic propellants, weather conditions at the splashdown location were described as calm. Wind speeds and wave heights were low, with no lightning within a 10-mile (16 km) radius, no more than a 25-percent probability of rain and good visibility.

Initial post-splashdown communications between Hopkins and SpaceX’s Crew Operations and Resources Engineer (CORE) proved somewhat comical. The CORE advised Hopkins that his crew had totaled 68 million miles (109 million km), having circled the globe 2,688 times in 167 days, six hours and 29 minutes.

“Thanks for flying SpaceX,” came the CORE’s call from the organization’s Hawthorne, Calif. headquarters. “For those of you enrolled in our Frequent Flyer Program, you’ve earned 68 million miles on this voyage.”

“And we’ll take those miles,” replied Hopkins. “Are they transferable?”

With split-second timing, the CORE came back with a chuckle. “And Dragon, we’ll have to refer you to our marketing department for that policy.”

A mere half-hour later, the blackened and scorched Dragon Resilience was hoisted aboard the Go Navigator and the four Crew-1 astronauts—who have now totaled more than 3.2 years of in-space time across their respective careers—disembarked shortly thereafter.

Notably, last December Glover became the most experienced African-American spacefarer, when he eclipsed the record of fellow NASA astronaut Stephanie Wilson, whilst Walker became only the third woman to command the ISS when she took the helm from Expedition 64’s Sergei Ryzhikov in mid-April. And when she in turn handed command to newly-arrived Crew-2 astronaut Aki Hoshide just 12 days later, she set a record for the shortest command of any ISS resident.

Not to be outdone, in December Hopkins became the first orbiting astronaut to be sworn into the United States’ newest military branch, the U.S. Space Force, whilst Noguchi not only became Japan’s most seasoned spacewalker, but also set the longest interval (nearly 16 years) between two sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) by any astronaut or cosmonaut.

The Crew-1 quartet’s remarkable mission got underway last 15 November, when Dragon Resilience rose to orbit atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from historic Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Boosted aloft by the “B1061” booster core—which went on to also launch Crew-2 last month—theirs was the first U.S. crewed launch in the hours of darkness since the twilight of the Space Shuttle era.

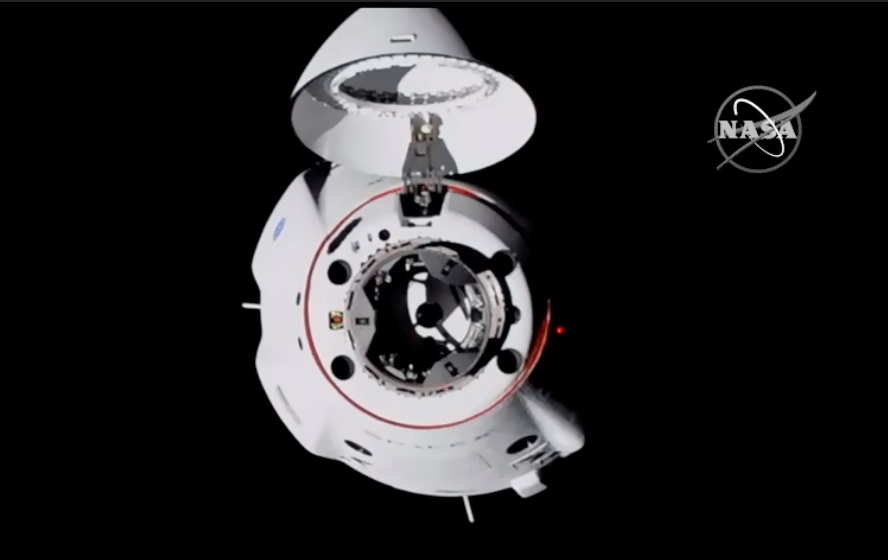

They docked smoothly at International Docking Adapter (IDA)-2, at the forward-facing port of the Harmony node, on 16 November, and were welcomed aboard the station by incumbent Expedition 64 Sergei Ryzhikov and his crewmates Sergei Kud-Sverchkov and Kate Rubins.

For the next five months, Expedition 64 became the first long-duration ISS increment to feature a crew as large as seven people. They welcomed three uncrewed visiting vehicles—the maiden voyage of SpaceX’s Cargo Dragon under the second-round Commercial Resupply Services (CRS2) contract in December, followed by a Russian Progress and Northrop Grumman Corp’s NG-15 Cygnus, both in February—and bade farewell to four.

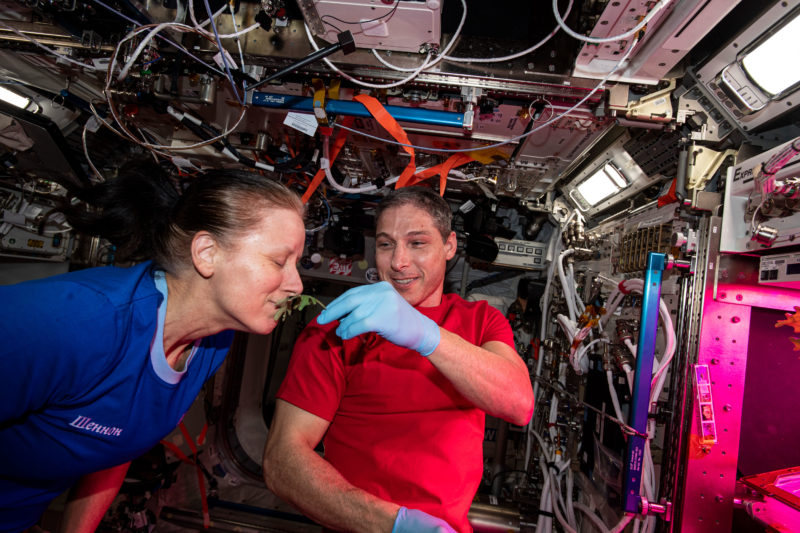

They supported hundreds of research investigations involving rodents, human stem cells and engineered heart tissues. And they supported six EVAs: one last November by Ryzhikov and Kud-Sverchkov for tasks associated with the Russian Operational Segment (ROS) and five more between January and March to activate hardware and augment the power of the U.S. Operational Segment (USOS).

Of the Crew-1 astronauts, Hopkins and Glover performed the first two U.S. EVAs, working to activate the Bartolomeo payloads-anchoring platform on Europe’s Columbus lab on 25 January, then wrapping up a four-year-long campaign of battery upgrades on 1 February. More recently, Kate Rubins was joined on two spacewalks—on the first by Glover and second by Noguchi—to prepare for the installation of the first ISS Roll-Out Solar Arrays (iROSAs), which will arrive aboard SpaceX’s CRS-22 Dragon in June. A final EVA by Hopkins and Glover on 13 March wrapped up a number of outstanding or incomplete tasks, including the relocation of jumper cables and the completion of Bartolomeo work.

All told, this left Hopkins with a career total of 32 hours in five spacewalks, Glover with 26 hours in four spacewalks and Noguchi with 27 hours in four spacewalks. Walker was alone among the Crew-1 team to participate in none of the EVAs.

But in a remarkable—even unprecedented—step, a decision was taken during the course of her stay to promote her to ISS Commander for a short spell near the end of the mission. On no previous occasion has an astronaut or cosmonaut been selected to command an expedition whilst in orbit, a decision which NASA says was made in order “to give more people a chance to command the station, even for a brief period”. With a career total of 330 days across her two space missions, Walker is now the second most experienced female space traveler, behind Peggy Whitson.

Following last month’s arrival of Soyuz MS-18 crewmen Oleg Novitsky, Pyotr Dubrov and Mark Vande Hei and the departure a few days later of Soyuz MS-17’s Ryzhikov, Kud-Sverchkov and Rubins, Expedition 64 officially gave way to Expedition 65, with Walker taking command on 15 April. Dragon Endeavour arrived at the station on 25 April, carrying astronauts Shane Kimbrough, Megan McArthur, Aki Hoshide and Thomas Pesquet, to produce an unusually large crew of 11 astronauts and cosmonauts.

Although three “direct handovers” of crews were performed in recent years—firstly in November 2013, then in September 2015 and most recently in the early fall of 2019—which temporarily increased the ISS population to nine, having as many as 11 souls aboard the station has been unseen since the end of the shuttle era. Not since May 2011, when 12 astronauts and cosmonauts occupied the ISS simultaneously for a few days during the Expedition 27 and STS-134 missions, has such a large number been aboard. And during that time, on 27 April, after only 12 days in command, Walker handed on-orbit authority for the ISS over to her “classmate and friend” Hoshide.

Dragon Resilience’s return to Earth, weather permitting, was originally targeted for Friday, 30 April, but one day prior NASA and SpaceX elected to postpone undocking and departure, following reviews of forecasted conditions in the primary splashdown zones. Of specific concern were projected wind speeds above mandated return criteria. Finally, it was announced Friday that splashdown would occur overnight Saturday/Sunday to produce only the second splashdown of a U.S. crewed vehicle in the hours of darkness, coming more than 52 years after the searing return of Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders from the Moon in December 1968.

And within hours of their return, the newest arrivals on Planet Earth were keen to share their feelings via Twitter. “Feels great to be back on Earth,” Hopkins told his followers. “I might miss the views outside of my Resilience room window tonight, but I’m happy to be home.” Added Glover, who last December was named to NASA’s “Artemis Team”, with a characteristic simplicity which perfectly summarized the achievements of Crew-1: “Home. Mission Complete.”

Congratulations to the fine people at SpaceX!