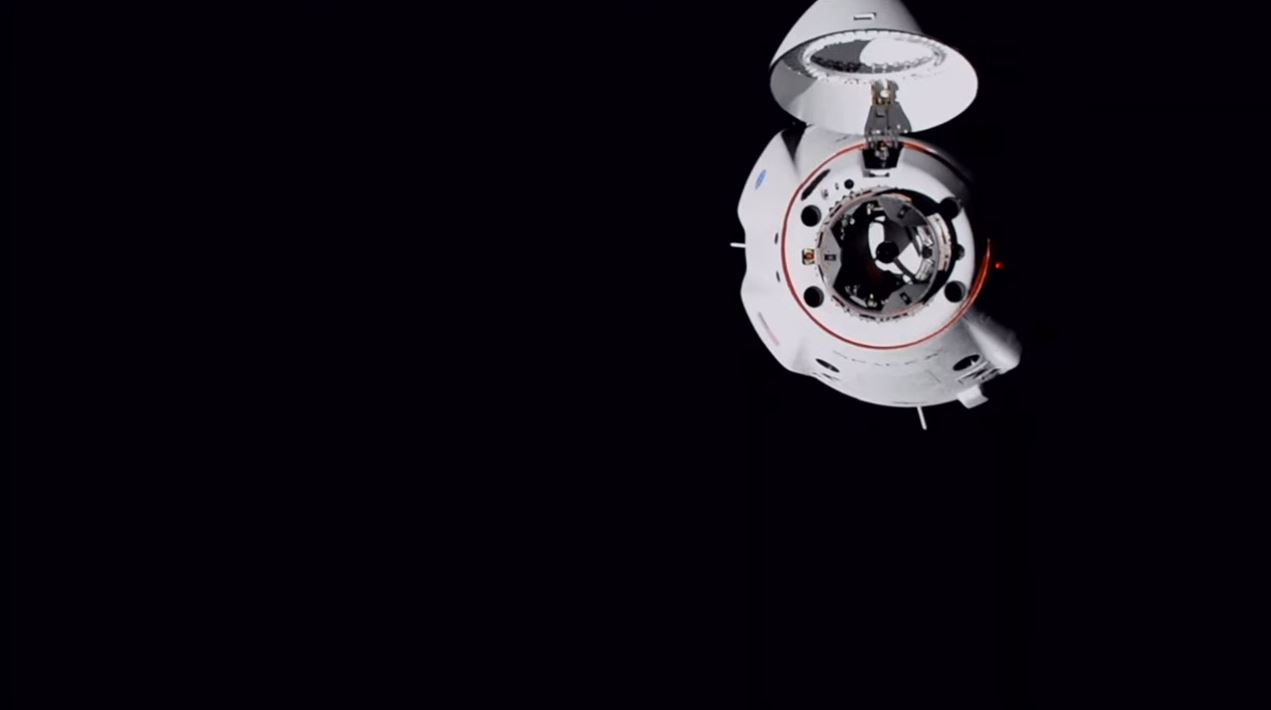

For the first time in International Space Station (ISS) history, the sprawling orbital outpost has a long-term crew of seven, following Monday night’s spectacular docking of Dragon Resilience at International Docking Adapter (IDA)-2 on the forward end of the Harmony node. Guided autonomously to its orbital home, but monitored closely by Crew-1 Commander Mike Hopkins and Pilot Victor Glover—joined on the flight by Mission Specialists Shannon Walker and Soichi Noguchi—the Crew Dragon moored at the ISS high above Idaho at 11:01 p.m. EST Monday, some 27 hours and 34 minutes after its spectacular Sunday night launch from historic Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

Less than two hours later, the hatches were opened and the newcomers were welcomed by the incumbent Expedition 64 team of Commander Sergei Ryzhikov and crewmates Sergei Kud-Sverchkov and Kate Rubins, ahead of a multi-month increment.

Monday’s perfect docking came at the end of a day-long approach profile which got underway shortly after launch. Around noon EST, after what Hopkins described as “a very nice night on-board Resilience”, Crew-1 was awakened by the strains of Phil Collins’ 1981 song “In The Air Tonight”.

At 9:22 p.m. EST, the Approach Initiation (AI) “burn” of the spacecraft’s thrusters was executed to bring Dragon Resilience within the ISS Approach Ellipsoid in order to reach Waypoint Zero, the first of three waypoints at 1,300 feet (400 meters) “below” the space station. They passed smoothly the remaining waypoints—Waypoint One at 720 feet (220 meters) and Waypoint Two at 65 feet (20 meters)—as Crew Dragon headed inward, solid as a rock. Beautiful views from Crew-1 revealed the IDA-2 docking interface at the end of Harmony, flanked by Japan’s Kibo and Europe’s Columbus labs to right and left.

Reaching Waypoint Two at 10:45 p.m. EST, Dragon Resilience held position to await a “Go/No-Go” decision for approach and docking from Mission Control. That approval came a few minutes later and the spacecraft inched towards a smooth docking at 11:01 p.m. EST, high above Idaho. For the next two hours later, pressurization and leak checks were conducted and Inter-Module Ventilation (IMV) hoses were hooked up between the vehicles.

Peering through the hatch window into Resilience, Rubins finally let her excitement get the better of her. “There appear to be four smiling crew members on the other side,” she exclaimed, as she paused from a check of condensation on the docking seal. At length, the hatches opened at 1:02 a.m. EST Tuesday and—clad in striking red polo shirts—first Hopkins, then Glover, then Walker and finally Noguchi floated aboard, all in jubilant spirits, to be engulfed in hugs and handshakes.

With seven people now aboard Expedition 64, this is officially the largest long-duration crew in the station’s 20-year history. Beginning with Expedition 1 in the fall of 2000, the ISS was initially occupied by three-member increments, although this was temporarily suspended in the spring of 2003 following the Columbia tragedy and a halt in regular construction and large-scale resupply capability.

Between May 2003 and July 2006, expeditions were reduced to two-man “caretaker crews”—an American and a Russian—before returning to three people with the arrival of German astronaut Thomas Reiter aboard STS-121. And as the ISS gradually expanded in terms of habitable volume and capability, the long-duration crew correspondingly expanded from three to six members for the first time in May 2009.

Since then, with astronauts and cosmonauts transported up and down from the station primarily aboard Russian Soyuz vehicles, this six-person capability has largely featured an “indirect handover” protocol. In other words, a given subset of a crew would depart the station, temporarily reducing the population to three, before a new Soyuz delivered their replacements to restore it back up to six.

A few exceptions to this rule have occurred and, for operational reasons, “direct handovers” have occasionally seen replacement crews arrive prior to the departure of their outgoing predecessors. One notable example occurred late last year, when Expedition 60/61 rose for a few days to nine personnel.

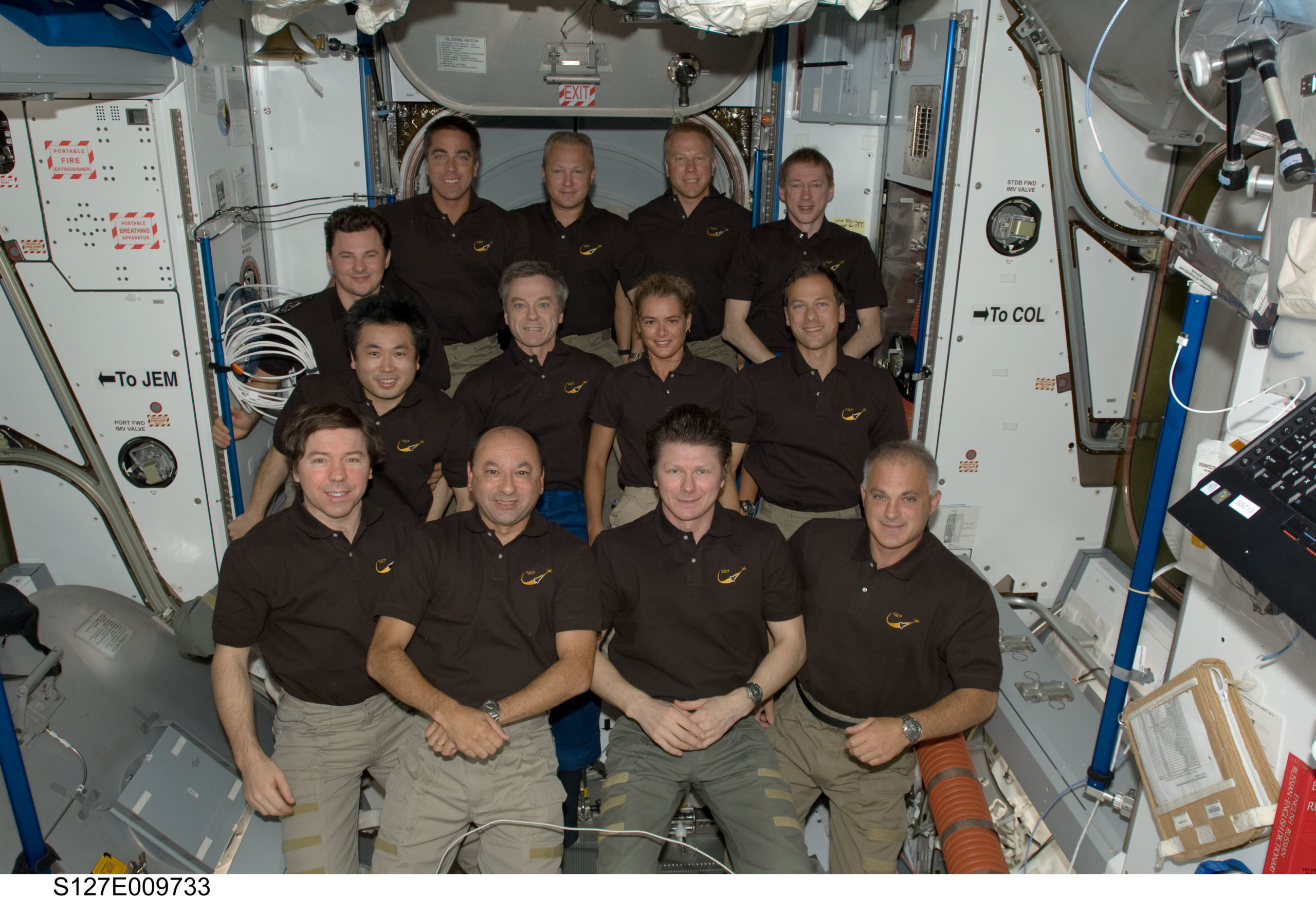

That is not to forget, of course, that crews temporarily expanded to larger numbers during docked Space Shuttle operations. On three particular missions—STS-127 in July 2009, STS-128 a month later and most recently STS-131 in April 2010—the presence of a six-strong ISS increment and a seven-member shuttle crew pushed the station’s population as high as 13.

But those large crews endured only for a few days. With the joining-up of the two halves of Expedition 64, this will be the first time that seven astronauts and cosmonauts will be in place for a “prolonged” period of time. And that is expected to permit a corresponding hike in science capability in the region of 70 hours of research per week aboard the ISS. According to ISS Program Manager Joel Montalbano, that equates to a virtual doubling of “crew-tended” science on a weekly basis.

How prolonged Crew-1’s stay will be remains open to question. During a welcome ceremony shortly after arrival, Hopkins noted an expectation that his crew will stay aboard for six months and in earlier comments made by SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell the direct-handover arrival of their replacements—Crew-2 aboard Dragon Endeavour—is anticipated about 4.5 months from now, in the late March timeframe.

“Exact end-date hasn’t been decided,” NASA’s Dan Huot recently told AmericaSpace. “It will largely be driven by the Crew-2 launch date, since we plan to do a direct handover.”

In any case, the seven-person Expedition 64 is in for a busy mission. No less than seven visiting vehicles are planned, including two flights—CRS-21 and CRS-22—by SpaceX’s new Cargo Dragon in December and March, a pair of Russian Progress cargo ships in the first quarter of 2021, Northrop Grumman’s NG-15 Cygnus in February, the long-awaited second uncrewed test of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner just after New Year, and the crewed Soyuz MS-18 in April.

Two Russian sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) are planned, the first by Ryzhikov and Kud-Sverchkov tomorrow (Wednesday) and another in February. These will prepare for the arrival of the new Nauka (“Science”) research lab and the disposal of the long-serving Pirs (“Pier”) module, which has been an integral part of the ISS since September 2001.

As such, it will become the first long-serving, permanent component of the ISS to be decommissioned and deorbited. Currently located on the nadir side of the Zvezda module, the departure of Pirs will open up a docking port for the arrival of Nauka, possibly as soon as next April.

And as many as three U.S. EVAs will occur before year’s end. Names of participating spacewalkers have yet to be announced, although three of the five U.S. Operational Segment (USOS) crew members—Rubins, Hopkins and Noguchi—are seasoned veterans, with a total of seven spacewalks and almost 46 hours of EVA time between them.

Key objectives include the installation of the Columbus Ka-Band Antenna (COL-Ka) and activation of the Bartolomeo payloads-anchoring platform on Europe’s Columbus lab—delivered to the station aboard SpaceX’s CRS-20 Dragon last March—together with the installation of a new lithium-ion battery on the P-4 truss segment, which blew a fuse last year.

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Crew-1 Completes Night Splashdown, Wraps Up 167-Day Mission « AmericaSpace