For the fifth occasion in less than six months, SpaceX will launch a Falcon 9 booster core for the fourth time on Wednesday, 22 April, as the organization resumes an aggressive campaign of missions in the face of the worldwide COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Liftoff of the veteran booster—tailnumbered “B1051”—is targeted to occur from historic Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida at 3:37 p.m. EDT and will loft another 60 Starlink internet communications satellites into low-Earth orbit. This also represents SpaceX’s seventh flight of 2020 and the eighth time in a row that it has performed missions on previously flown boosters.

Wednesday’s launch comes on the back of four previous batches of Starlink satellites so far this year, as well as last month’s CRS-20 cargo mission to the International Space Station (ISS) and the triumphant in-flight abort test of a Crew Dragon spacecraft in January. There has been much emphasis in recent weeks upon the timing of the Demo-2 flight of Crew Dragon, which is scheduled to launch on 27 May and will see veteran NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken fly to the International Space Station (ISS). In so doing, they will become the first pair of U.S. citizens to launch aboard a U.S.-made spacecraft, atop a U.S.-built rocket, and from U.S. soil, since the end of the Space Shuttle Program in July 2011. Interestingly, Hurley was pilot of STS-135, the last shuttle flight, which affords him a unique position as a torchbearer from one generation of U.S. piloted space vehicles to the next.

And with the steadily worsening COVID-19 situation, intense shielding has been put in place around spacefarars-in-waiting, as was seen in the recent pre-launch quarantine of Expedition 63 crewmen Chris Cassidy, Anatoli Ivanishin and Ivan Vagner. So too has the processing of future SpaceX payloads suffered. Plans to fly Argentina’s SAOCOM-1B Earth-imaging satellite, originally slated for late March, have been indefinitely postponed, as has the third Global Positioning System (GPS) Block III satellite, which is now targeted for no sooner than 30 June. And with two failures of booster cores to land on the Autonomous Spaceport Drone Ship (ASDS) and a premature first-stage engine shutdown during the most recent SpaceX mission in March, it seems likely that at least another launch will be desirable before Hurley and Behnken climb atop their own Falcon 9.

Of the four booster cores to have flown a fourth time so far since November 2019, only B1049—which completed its most recent mission in January—survives and is capable of launching again. Two others, B1056 and B1048, failed to land on the ASDS, whereas B1046 was intentionally scuppered after its final role supporting January’s Crew Dragon in-flight abort.

When B1051 launches on Thursday, it will log its fourth flight in only 13 months, having previously delivered the Demo-1 Crew Dragon in March 2019, Canada’s Radarsat Constellation Mission (RCM) last June and a 60-strong Starlink batch in late January. The payload fairing is also seeing its second use, having earlier encapsulated the AMOS-17 payload last August.

Scorched and blackened from three previous high-energy ascents and re-entries, B1051 has flown from all three of SpaceX’s currently active launch pads: Space Launch Complex (SLC)-40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., Space Launch Complex (SLC)-4E at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., and KSC’s Pad 39A. It has also returned smoothly to execute two landings on the East Coast drone ship, “Of Course I Still Love You”, and last summer descended through thick fog to alight on the West Coast ground pad.

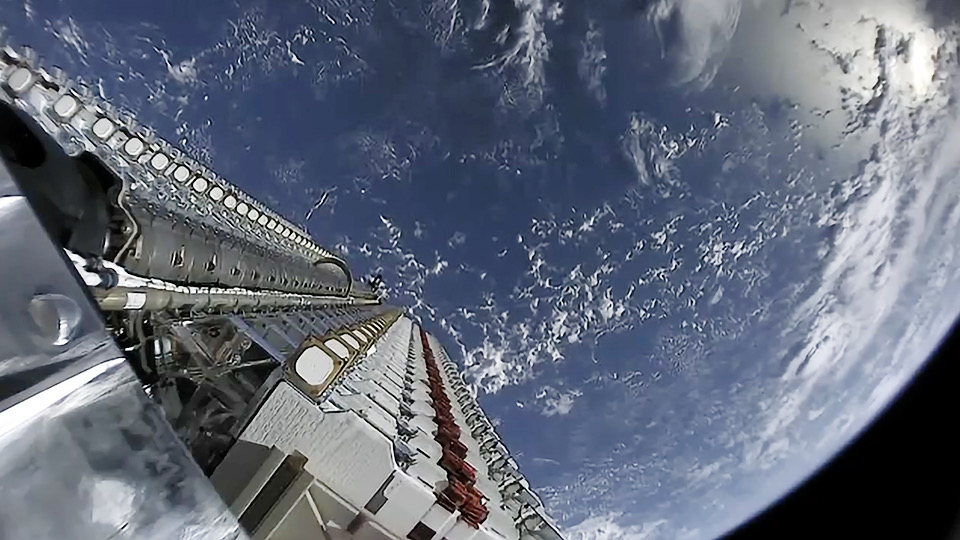

And if you happen to think that seeing B1051 in action again has a touch of “Groundhog Day” about it, you would not be far wrong, for this will also be the sixth dedicated launch of Starlink satellites in only five months. Batches of 60 of these low-orbiting internet communications satellites were despatched in November 2019, twice in January and once apiece in February and March. Prior to those flights, a series of Starlink “test satellites” were launched in February 2018 and May of last year.

The $10 billion Starlink program, unveiled by SpaceX CEO Elon Musk in Seattle, Wash., in January 2015, has been described as a means of revolutionizing low-cost broadband provision. He identified it as a means of opening the way for competitively-priced services for urban regions and rural and underserved areas of the United States. Under the announced plan, an eventual constellation of 12,000 satellites could handle up to half of all backhaul communications traffic and a tenth of all local internet traffic in high-population-density cities by the mid-2020s.

Late in 2016, SpaceX described the concept as “non-geostationary” and revealed Starlink’s initial coverage would span the Ku-band and Ka-band regions, between 12-18 GHz and 26.5-40 GHz, respectively. By the late spring of the following year, plans were laid for a second orbital “shell” of satellites to utilize the V-band at 40-75 GHz, which is not routinely used for commercial communications purposes. Previously, the V-band has seen service for millimeter-wave radar research and scientific applications, but it reportedly also has promise for high-capacity terrestrial millimeter-wave communications networks.

SpaceX’s original intent was for 4,425 Ku-/Ka-band Starlinks to reside at an altitude of 710 miles (1,150 km) and 7,518 V-band birds to sit at 210 miles (340 km), producing a total population of these small satellites by the mid-2020s. However, in November 2018 SpaceX received licensing from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to operate a third of the Ku-/Ka-band complement—some 1,584 satellites—at just 340 miles (550 km), much lower than initially planned.

This will produce a relatively short operational lifetime of around five years, before they are maneuvered into a disposal orbit for controlled re-entry. SpaceX has explained that all satellite components are “100-percent demisable” and exceed “all current safety standards”, but the sheer volume of Starlinks to be launched in a relatively short period has aroused lingering controversy, both in terms of the work of astronomers and adding to ongoing debate about the effect of space debris.

Two Starlink test satellites, Tintin-A and Tintin-B, were launched in February 2018 and successfully validated the phased-array broadband antenna from an orbital perch 320 miles (515 km) above Earth. Then, last May, the first 60 “production-design” Starlink satellites were launched atop B1049. Although three of the satellites failed shortly after reaching orbit, the remainder are still healthy. More recently, in November 2019 and on three occasions in January and February of this year, a further four batches of 60 Starlinks apiece were boosted to space on three veteran Falcon 9 rockets. SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell has already confirmed plans to launch further 60-strong sets of Starlinks approximately every two weeks throughout 2020, raising the likelihood that many hundreds of these small satellites will be in orbit by next New Year’s Eve. And that pledge looks set to be met not only with words, but also with the roar of rocket exhaust, too, for Saturday’s launch will come only a few weeks since the most recent Starlink flight.

As has become customary on these missions, the Falcon 9 was transported to the pad on Thursday, 16 April, for its Static Fire Test with the Starlink payload “stack” already in place. This is quite different to other SpaceX customers, following the September 2016 anomaly in which the heavyweight Amos-6 communications satellite was lost in a pre-flight explosion on the pad. Following the Static Fire Test, SpaceX initially announced that it was targeting 3:16 p.m. EDT on Thursday, 23 April, for launch. But on Monday came the surprising news that it would instead aim to fly one day sooner. “With a more favorable weather forecast for launch and landing, now targeting Wednesday, 22 April at 3:37 p.m. EDT for this week’s Falcon 9 Starlink mission,” it reported Monday evening.

Indeed, according to the 45th Weather Squadron at Patrick Air Force Base, the outlook for Wednesday is 90-percent-favorable, compared to a more iffy 60-percent on Thursday. “Dry conditions with light east winds are expected during the launch window on Wednesday,” it reported in its L-2 weather briefing on Monday. “The main concern during the window will be for a few cumulus clouds as the east-coast sea breeze moves inland early in the afternoon.”

Should Wednesday’s attempt be scrubbed, the outlook is less favorable on Thursday, 23 April. “Another strong front moving into the southeastern U.S. on Thursday will lead to strong and gusty south winds across the Spaceport during the backup launch window,” it was noted. “While the front itself is expected to remain north of Central Florida during the day, increasing moisture across the region will bring a chance for showers and storms.”

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

Missions » Commercial Space » Starlink »