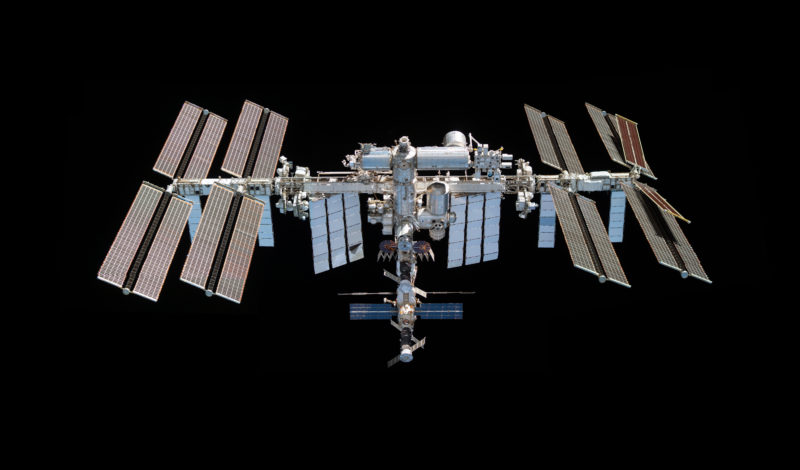

In a highly anticipated move, the Biden-Harris Administration has formally committed NASA to extend operations aboard the International Space Station (ISS) through 2030, wrapping up three full decades of permanent human habitation aboard the sprawling multi-national orbital outpost.

“The International Space Station is a beacon of peaceful international collaboration and for more than 20 years has returned enormous scientific, educational and technological developments to benefit humanity,” said NASA Administrator and one-time shuttle flyer Bill Nelson. “I’m pleased that the Biden-Harris Administration has committed to continuing station operations through 2030.”

“The United States’ continued participation on the ISS will enhance innovation and competitiveness, as well as advance the research and technology necessary to send the first woman and first person of color to the Moon under NASA’s Artemis Program and pave the way for sending the first humans to Mars,” Nelson continued. “As more and more nations are active in space, it’s more important than ever that the United States continues to lead the world in growing international alliances and modeling rules and norms for the peaceful and responsible use of space.”

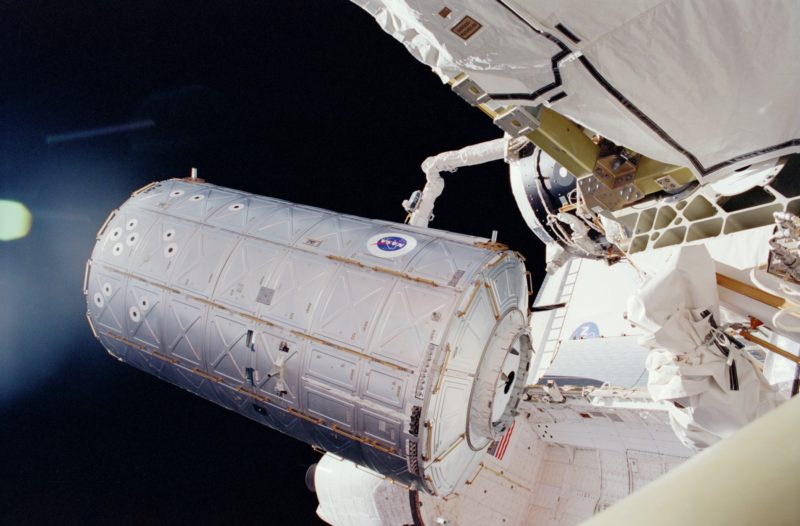

Construction of the ISS got underway on 20 November 1998, when a Russian Proton-K rocket lifted the 42-foot-long (12.5-meter) Zarya module into orbit from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Two weeks later, five astronauts and a single cosmonaut aboard shuttle Endeavour on STS-88 delivered and installed the Unity node onto Zarya to create the cornerstone of what would become the largest and most complex engineering edifice in history, the brightest artificial object in Earth’s skies and the biggest human-made satellite ever placed into space.

Two years later, on 2 November 2000, the Soyuz TM-31 spacecraft docked safely at the nascent ISS, bringing aboard Expedition 1 Commander Bill Shepherd of NASA and his Russian crewmates Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev.

They spent more than 4.5 months at the station and kicked off an unbroken chain of human occupation which continues to this very day. All told—and including the seven-strong Expedition 66 team currently on board—a total of 249 men and women from 19 sovereign nations have visited the ISS, two of whom spent almost a continuous year in orbit.

More than 3,000 research investigations involving over 4,200 scientists from 110 countries and areas around the world have been conducted and 1.5 million students annually are involved in ISS-based Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) activities.

Today’s space station is barely recognizable from the facility occupied by Shepherd, Gidzenko and Krikalev more than two decades ago. At the start of Expedition 1, it comprised just three large pressurized modules—Zarya, Unity and Russia’s Zvezda service module—but over the years its size, internal volume and capabilities expanded with the U.S. Destiny lab, Japan’s Kibo and Europe’s Columbus facilities, the Harmony and Tranquility nodes and the multi-windowed cupola.

Added to that list, an expansive Integrated Truss Structure (ITS) supports the station’s power-generation and cooling infrastructure and Russia’s long-delayed Nauka science lab was delivered and activated just last summer.

Commercial entities, too, have been increasingly courted, with the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) installed in 2016 and contracts inked with Houston, Texas-based Axiom Space, Inc., in January 2020 to build and deliver the first of a suite of pressurized research facilities from 2024 onwards.

Six of the station’s eight giant Solar Array Wings (SAWs) are in the process of being upgraded with ISS Roll-Out Solar Array (iROSA) technology to augment their power-generating capabilities for an anticipated surge in commercial research activity over the next few years.

Station operations had already been extended deep into the present decade. As long ago as March 2010, NASA and its international partners—the European Space Agency (ESA), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and Russia’s Roscosmos—found “no identified technical constraints” to preclude operations beyond the 2015-2020 planning horizon.

That was subsequently pushed to “at least 2024” in January 2014 remarks by then-President Barack Obama, with the partners actively “working to certify on-orbit elements through 2028”. For its own part, in November 2019 ESA formally committed itself to ISS operations through 2030.

3 Comments

3 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:Vande Hei, Crewmates Back Home After Longest Single U.S. Human Space Mission - AmericaSpace

Pingback:Vande Hei Discusses Longest Single U.S. Human Space Mission - AmericaSpace

Pingback:Ax-1 Crew Arrives Safely at Space Station - AmericaSpace