Planetary debris disks, or protoplanetary disks, are some of the most interesting phenomena in astronomy – these giant clouds of dust and gas surrounding young stars are the birthplaces of new planets. Now, astronomers studying one of these disks have found structures never seen before, giant “ripples” which are arch-like or wave-like in appearance.

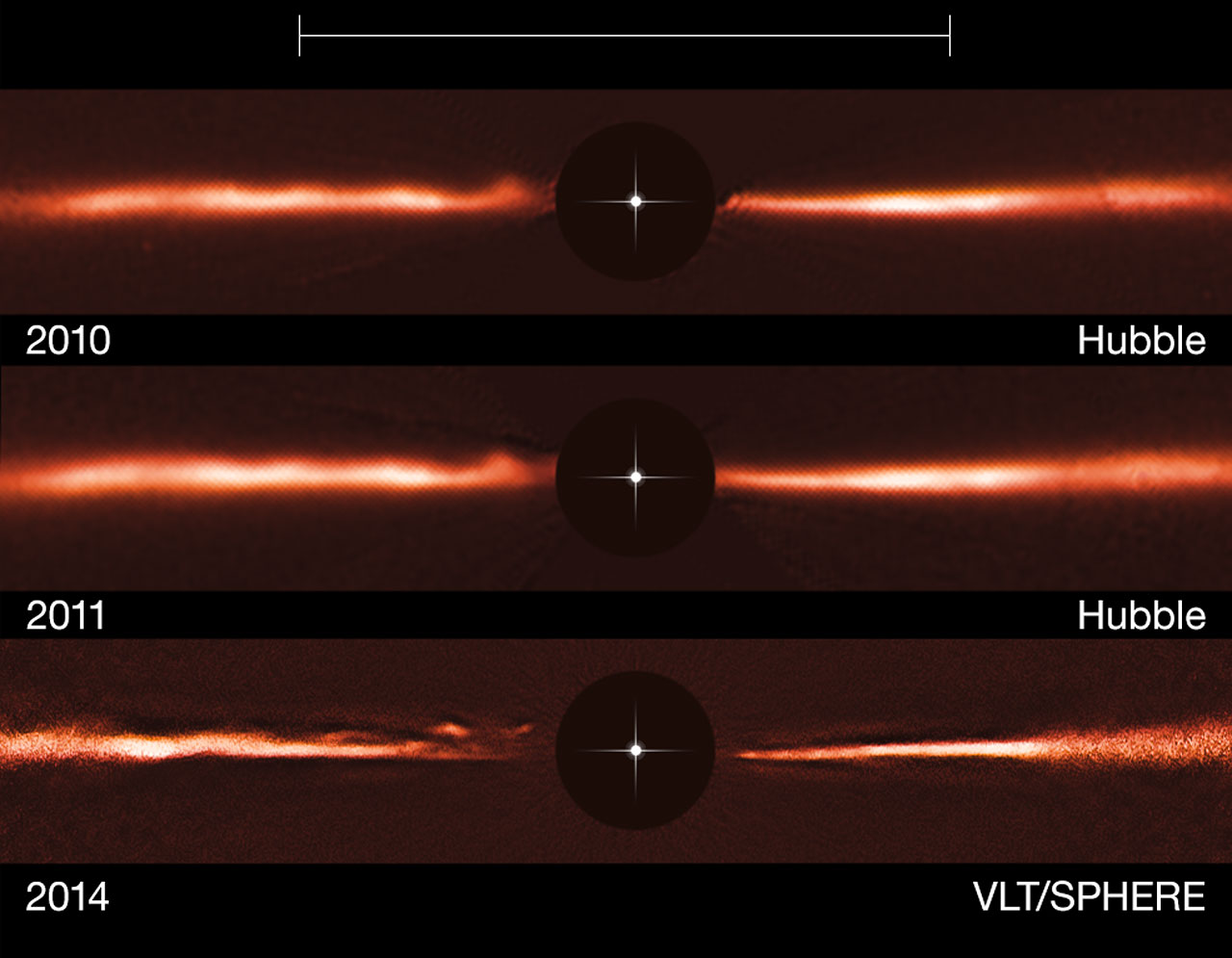

The structures observed are unlike any seen before, and weren’t even predicted by astronomers. They were discovered using the Hubble Space Telescope (NASA/ESA) and Very Large Telescope (ESO). The new results were published in the journal Nature on Oct. 8, 2015.

The unusual ripples were discovered in the debris disk surrounding the young, nearby star AU Microscopii, 32 light-years from Earth. Most of the debris in this disk is thought to be composed of asteroids which which have collided and have been ground down to dust.

As with other similar disks, astronomers have been studying it for any signs of possible planetary formation processes going on, such as clumpiness or other warped features. The new features were first spotted in 2014 by the Very Large Telescope, using the newly installed SPHERE instrument.

“Our observations have shown something unexpected,” explained Anthony Boccaletti of the Observatoire de Paris, France and lead author of the paper. “The images from SPHERE show a set of unexplained features in the disc which have an arch-like, or wave-like, structure, unlike anything that has ever been observed before.”

At least five wave-like arches have been seen, similar in appearance to ripples in a pool of water. The team then examined earlier images of the debris disk from the Hubble Space Telescope, taken in 2010 and 2011, and confirmed the findings from the VLT. To the surprise of the astronomers, the images showed that the ripples had also changed over time, that they were moving rapidly through the debris disk.

“We reprocessed images from the Hubble data and ended up with enough information to track the movement of these strange features over a four-year period,” explained team member Christian Thalmann (ETH Zürich, Switzerland). “By doing this, we found that the arches are racing away from the star at speeds of up to about 40,000 kilometers/hour!”

Interestingly, the ripples further from the star appeared to be moving faster than those closer in, and three of the ripples may even be moving fast enough to eventually escape the gravitational pull of the star. That is, as it sounds, highly unusual, according to the astronomers, and means that planets are probably not the cause of the phenomenon – but then what is?

“Everything about this find was pretty surprising!” noted co-author Carol Grady of Eureka Scientific, USA. “And because nothing like this has been observed or predicted in theory we can only hypothesise when it comes to what we are seeing and how it came about.”

The cause of the weird ripples is still unknown, but astronomers do have theories.

“One explanation for the strange structure links them to the star’s flares. AU Mic is a star with high flaring activity – it often lets off huge and sudden bursts of energy from on or near its surface,” said co-author Glenn Schneider of Steward Observatory, USA. “One of these flares could perhaps have triggered something on one of the planets – if there are planets – like a violent stripping of material which could now be propagating through the disc, propelled by the flare’s force.”

Some explanations have already been ruled out, including the collision of two massive and rare asteroid-like objects releasing large quantities of dust, or spiral waves triggered by instabilities in the system’s gravity.

“It is very satisfying that SPHERE has proved to be very capable at studying discs like this in its first year of operation,” added Jean-Luc Beuzit, a co-author of the new study and leader of the development of SPHERE itself.

Planetary debris disks such as this one are the birthplaces of new planets, which form from the massive clouds of dust and gas. Many such disks have been found and studied by astronomers, and even baby planets, still extremely hot, have been identified within some of them. As is thought to have occurred with the formation of our own Solar System, the forming planets clear out gaps of relatively empty space within the disk, making their locations easier to see by astronomers. Observing other debris disks will also help astronomers to learn more about how our own Solar System formed, and how similar it is to other planetary systems.

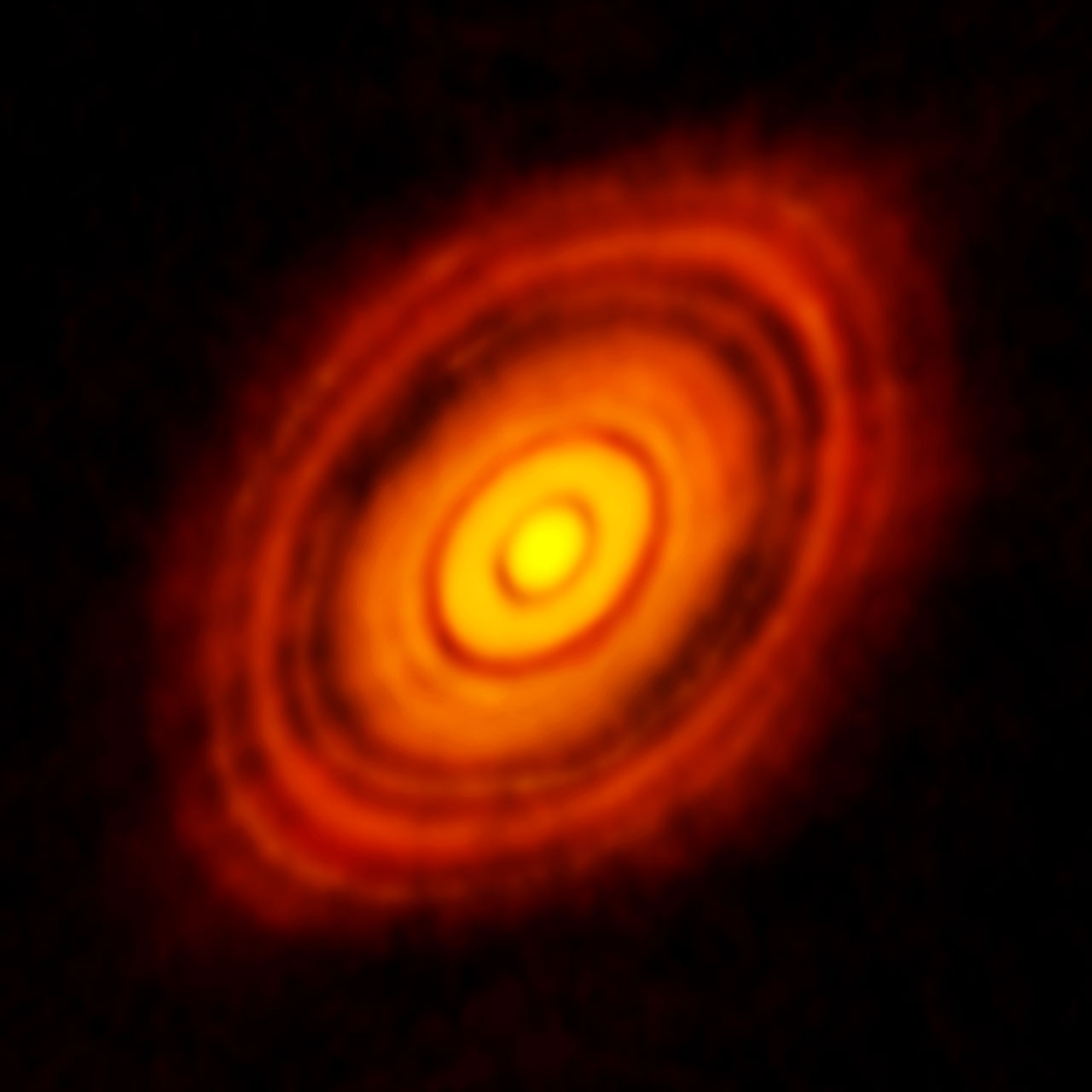

In 2014, a new image of a similar debris disk was released by ESO, showing unprecedented detail. The image was taken by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), showing the debris disk surrounding the young star HL Tauri, including ring gaps. As with other debris disks, young planets are thought to be forming within the gaps in the disk.

The team will continue to study the debris disk surrounding AU Microscopii, to try and better understand what is happening.

This research was presented in a paper entitled “Fast-Moving Structures in the Debris Disk Around AU Microscopii”, in the journal Nature on Oct. 8, 2015.

More information about the Hubble Space Telescope is available here.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace