After two frustrating months, SpaceX has successfully launched its third Falcon 9 v1.1 mission of 2014, boosting six Orbcomm Generation-2 (OG-2) satellites into a circular orbit of approximately 460 x 460 miles (750 x 750 km), inclined 52 degrees to the equator, on behalf of Orbcomm, Inc. It is hoped that the small satellites will remain operational for at least five years, providing two-way messaging services for global customers. Liftoff of the Falcon took place at 11:15:00 a.m. EDT Monday, 14 July, from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla. It occurred near the end of the 2.5-hour “window” and came only days after the Air Force officially certified SpaceX as having undertaken three successful consecutive flights, thereby placing the Hawthorne, Calif.-based launch services provider one step closer to its much-publicized and bitterly contested goal of delivering high-priority national security payloads into orbit.

Originally scheduled for launch in early May—just three weeks after SpaceX launched its third dedicated Dragon cargo flight (SpX-3) to the International Space Station (ISS)—the OG-2 mission suffered a considerable helium leak in the Falcon 9 v1.1’s first stage, which forced a lengthy postponement. The vehicle was returned from its vertical position on SLC-40 to a horizontal configuration and was returned to the integration facility for inspections. A revised launch target of early June quickly proved untenable, although SpaceX eventually settled on a “No Earlier Than” date of the 15th. In spite of fears that the mission would slip further into July, due to a planned maintenance down period involving Eastern Range tracking assets, it was eventually decided to proceed with a launch attempt on the 20th. A technical issue with the vehicle caused this attempt to be scrubbed, whilst a second effort to get the Falcon 9 v1.1 airborne on 21 June fell foul to particularly dynamic weather in the Cape Canaveral area. Any chances of “third-time-lucky” charm proved fruitless, when the third attempt on 22 June was also scrubbed, amid poor weather conditions, due to what SpaceX described as the need “to address a potential concern identified during pre-flight checks”. Hopes to make another try on 24 June were quickly dashed and SpaceX and Orbcomm revealed that the mission would slip into mid-July.

“We are now targeting Monday, 14 July, with Tuesday, 15 July as a backup,” Orbcomm announced on its website, “pending approval from the Air Force Range. This provides the necessary time to ensure the highest possible mission assurance and allows the Range to complete their previously scheduled maintenance.” By the second week in July, these dates had been refined, with the primary date remaining the 14th, but the backup date moved 24 hours to the 16th. Orbcomm explained that the slippage was “due to scheduling conflicts at the Cape”. Following the customary static test-firing of the Falcon 9 v1.1’s nine Merlin-1D first-stage engines at 3:00 p.m. EDT on Friday, 11 July, a Launch Readiness Review (LRR) on Saturday gave formal approval to proceed with the fourth attempt to get the six OG-2 satellites into orbit on Monday morning. The 2.5-hour launch window extended from 9:22 a.m. until 11:54 a.m.

Monday dawned with a 70-percent likelihood of acceptable weather conditions at the Cape and SpaceX technicians set to work chilling down the first-stage fuel and oxidizer lines, preparatory to loading cryogenic liquid oxygen and a refined form of rocket-grade kerosene (known as “RP-1”) aboard the Falcon 9 v1.1. By 6:37 a.m. EDT, according to AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker, all propellants were aboard the vehicle. The expansive length of today’s window offered a good chance, barring any further technical issues, that the OG-2 mission would finally fly, but this hope was quickly arrested with gloomy news. The projected T-0 time was moved back to 11:44 a.m., just ten minutes before the scheduled closure of the window. On its Twitter page, SpaceX noted that “Out of an abundance of caution, the team took some extra time this morning to look at a potential ground systems issue”, but stressed that they had “resolved any concern” and were “moving forward with the countdown” towards the revised T-0.

Despite SpaceX’s confidence, aiming for so late in the window meant that any technical or weather-related issue during the Terminal Countdown—which kicks off at T-10 minutes, following the final “Go/No-Go” poll of all stations—would result in an automatic scrub. Then, at 9:10 a.m., it was announced that T-0 had been moved slightly earlier to 11:15 a.m., giving the Falcon 9 v1.1 a 40-minute block of time in which to launch. However, weather conditions did not appear to be on SpaceX’s side, deteriorating slightly to about 60 percent favorable. During the latter stages of the countdown, gases streamed from the Falcon 9 v1.1, due to continuous cryogenic boil-off, which was rapidly replenished to flight levels until close to the time of launch. SpaceX’s live webcast began at 11:00 a.m. EDT, with Falcon 9 Product Director John Insprukter reporting that the six OG-2 satellites had transferred to internal power and that, despite the deteriorating weather conditions, upper-level winds at the Cape were acceptable.

At 11:02 a.m., with the clock at T-13 minutes, the standard poll of all 13 stations was conducted by the Launch Director, producing a unanimous “Green” (“Go for Launch”), and the Terminal Count got underway shortly afterwards, at T-10 minutes. Now running on the autosequencer, the nine Merlin-1D engines were chilled down in order to provide pre-launch thermal conditioning. With all propellant tanks verified to be at their correct pressures, the launch pad’s “strongback” was completely retracted by T-4 minutes. The Flight Termination System (FTS)—tasked with destroying the vehicle in the event of a major accident during ascent—was placed onto internal power and armed. By T-2 minutes and 15 seconds, the first stage propellant tanks were verified to be at flight pressure. “Range Green” came the final call from Air Force Range personnel.

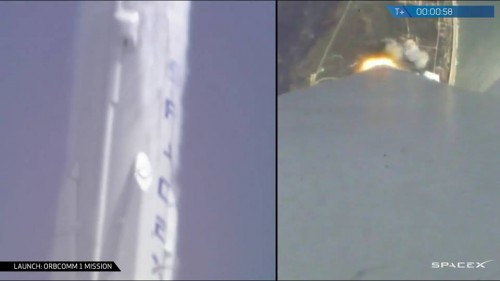

At T-1 minute, the flight computer was confirmed to be in control of the vehicle and the second-stage propellant tanks reached flight pressures. SLC-40’s ‘Niagara’ deluge system began to flood the pad surface with 30,000 gallons (113,500 liters) of water per minute to suppress acoustic waves radiating from the Merlin-1D engine exhausts. At T-3 seconds, the nine Merlins roared perfectly to life, ramping up to their required parameters, and at 11:15:00 a.m. the third mission of the Falcon 9 v1.1 in 2014 (and its fifth flight overall) was at last airborne. At the instant of liftoff, the nine first-stage engines generated 1.3 million pounds (590,000 kg) of thrust, pushing the vehicle uphill for the first three minutes of the flight. Their propulsive yield gradually rose to 1.5 million pounds (680,000 kg) in the rarefied high atmosphere. “Unlike airplanes, a rocket’s thrust actually increases with altitude,” explained SpaceX. “Falcon 9 generates 1.3 million pounds of thrust at sea level, but gets up to 1.5 million pounds of thrust in the vacuum of space. The first-stage engines are gradually throttled near the end of first-stage flight to limit launch vehicle acceleration as the rocket’s mass decelerates with the burning of fuel.”

With around 1,970 seconds of test time and a lengthy qualification program, SpaceX has expressed supreme confidence in the Merlin-1D. During a full-duration-mission firing in June 2012 in McGregor, Texas, the engine operated at or above the power and duration required for a Falcon 9 launch. The Merlin-1D has a vacuum thrust-to-weight ratio in excess of 150:1, making it the most efficient liquid-fueled rocket engine in history. The ignition system for the v1.1′s first stage was tested in April 2013. The stage also includes four extendible landing legs, manufactured from carbon-fiber and aluminum honeycomb, to support a series of tests which SpaceX CEO Elon Musk hopes will lead to vertical-takeoff-vertical-landing (VTVL) capability by the latter half of the present decade.

Immediately after clearing the SLC-40 tower, the Falcon 9 v1.1 executed a combined pitch, roll, and yaw program maneuver to establish itself onto the proper flight azimuth for the injection of the six OG-2 satellites into low-Earth orbit. Eighty seconds into the ascent, the vehicle passed Mach 1 and experienced a period of maximum aerodynamic stress (known as “Max Q”) on its airframe. At 11:17:10 a.m., as planned, two of the nine Merlin-1D engines shut down to reduce the rate of acceleration, ahead of Main Engine Cutoff (MECO) and separation of the first stage. The remaining seven Merlin-1Ds continued to burn hot and hard, finally shutting down at 11:17:38 a.m., and the first stage was jettisoned about three seconds later. “Between the first and second stages is the ‘interstage’,” explained AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker. “The interstage is a composite structure that connects the first and second stages and holds the release and separation system. The Falcon 9 uses an all-pneumatic stage separation system for low-shock, highly reliable separation.” With the first stage thus jettisoned, the turn then came for a single ‘burn’ by the Falcon’s restartable second stage, which ignited for the first time at 11:17:49 a.m. Less than 30 seconds later, the protective payload fairing was discarded, exposing the OG-2 payload to the space environment for the first time. “At this height in the atmosphere,” noted the Tracker, “there is no threat of damage to the delicate satellites from the rushing air.”

The second stage’s single Merlin-1D Vacuum engine, with a maximum thrust of 180,000 pounds (81,600 kg), burned for almost seven minutes to deliver the payloads into orbit. It finally shut down at 11:24:35 a.m., less than ten minutes after leaving Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. At the time of writing, the expired second stage and attached OG-2 satellites were ‘coasting’, ahead of payload separation at 11:30 a.m. EDT.

Today’s successful delivery of these satellites will undoubtedly come as a relief for both SpaceX and Orbcomm; the former has returned to flight after many weeks of delay and media criticism, whilst the latter can at last enjoy one of its payloads in orbit. Each OG-2 satellite weighs 380 pounds (170 kg) and, when fully deployed, each will measure 42.7 feet (13 meters) x 3.3 feet (1 meter) x 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) and generate about 400 watts of electrical power. Built by Sierra Nevada Corp., the original plan was to launch 18 OG-2 satellites, the first of which flew ‘piggyback’ on SpaceX’s first dedicated Dragon mission in October 2012. Unfortunately, an upper-stage engine shortfall of the Falcon 9 v1.0 vehicle caused the satellite to be injected into a low orbit of just 125 x 200 miles (200 x 320 km), instead of the intended 220 x 470 miles (350 x 750 km). As a result, the satellite re-entered Earth’s atmosphere to destruction a few days later.

In the aftermath of today’s launch of six OG-2 satellites, a further 11 are expected to fly aboard another Falcon 9 v1.1, although the target date has yet to be announced. Orbcomm announced in May 2008 that SNC would build a total of 18 satellites for a fee of $117 million, with an option for up to 30 others. A few weeks later, Orbcomm chose Argon ST, a subsidiary of Boeing, to develop advanced communications payloads to increase subscriber capacity by up to 12 times over earlier satellites, as well as transmitting data at higher speeds and quantities. Designed with Automatic Identification System (AIS), it is expected that the OG-2 network will be marketed by Orbcomm to U.S. and international coast guards and government agencies, as well as private security and logistics companies.

By 2009, Orbcomm had settled on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 as its vehicle of choice, with the inaugural launches originally anticipated the following year, but postponed several times due to delays and schedule slips.

Prior to today’s launch, 45 Orbcomm satellites have been delivered into orbit since July 1991, aboard a wide range of vehicles, including Europe’s Ariane 4, the air-launched Pegasus booster, Orbital Sciences Corp.’s Taurus, China’s Long March 4B, India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), and Russia’s Cosmos-3M. Initial “Concept Demonstration Satellites” led to the OG-1 network and a replenishment series of “Quick Launch” missions, with the OG-2 series intended to supplement and eventually replace the first generation. “Due to their high efficiency and modular design, these satellites have substantially more capacity to service a larger number of subscribers, thus making the network more efficient with few satellites than the OG-1 satellites that are currently in orbit,” explained Pat Remias, SNC’s Space Systems senior director of programs. “SNC has established a satellite production line in our Louisville facility to integrate and test each vehicle rapidly, with up to six satellites processing simultaneously.”

As described by Mike Killian in a recent AmericaSpace article, SpaceX was last week officially certified by the Air Force as having flown three successful consecutive missions. This certification is a major milestone (and a mandatory pre-requisite) in the certification process for any company seeking to win business from the Air Force’s Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) Program, including the award of major contracts to deliver classified national security payloads into orbit for the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). Since September 2013, SpaceX’s uprated Falcon 9 v1.1 has flown three wholly successful, back-to-back missions—delivering the CASSIOPE science satellite in September 2013, followed by the commercial geostationary communications satellites SES-8 in December and Thaicom-6 in January 2014—and it was revealed that the Air Force has now concluded its thorough evaluation of the vehicle’s design, reliability, process maturity and safety systems. Today’s successful launch of the OG-2 satellites will undoubtedly bolster the confidence of SpaceX as it presses on toward major government contracts.

– Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » Commercial Space » ORBCOMM » SpaceX OG2 M1 »

Did anyone else notice the sudden jump off the pad and then a decrease in momentum followed by a slight increase to clear the pad? Or was this just an optical illusion?

Looks like the 1st stage blew up on the water landing or wave submersion…further analysis needed…Does anyone know will the ocean water actually ignite if subjected to direct rocket engine flame exhaust on landing? What is that burning at 2,000 to 3,000 Celsius?

Ok now can we get Lockheed Martin to dust off the X-33 from the shelf and get going on SSTO???

Any news on the first stages return to Earth???????

Thanks for any info.