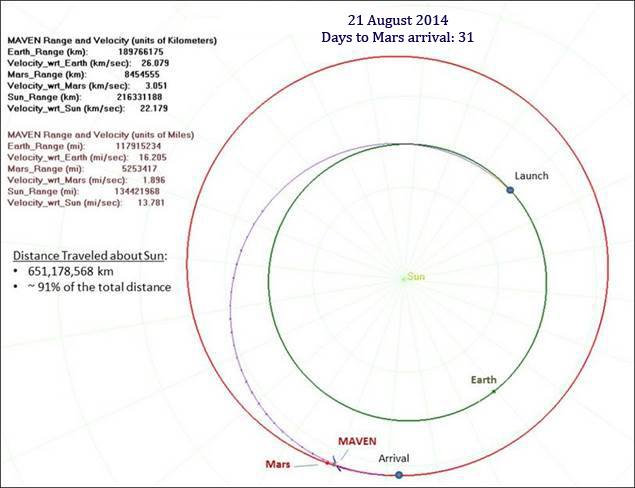

The spacecraft tasked with carrying out NASA’s first mission devoted to understanding the Martian upper atmosphere is now just 30 days out from the Red Planet, having so far covered 405 million miles over the last nine months, as it quietly cruises the void between our worlds at over 16 miles per second (Earth-centered velocity). Now, with over 90 percent of the long journey completed, and all of the spacecraft’s instruments operating nominally, NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission, or MAVEN, is on track for Mars orbit insertion (MOI) at 10:00 p.m. EDT on Sept. 21.

“At the end of July we went into a pre-Mars Orbit Insertion moratorium,” said David Mitchell, MAVEN Project Manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “All systems required for a safe Mars Orbit Insertion remain powered on. But other systems like the instruments are shut down until late September because they are not needed for a successful MOI. We want the spacecraft system to be as ‘quiet’ as possible and in the safest condition during the critical event on September 21st.”

MAVEN will join an ever-growing fleet of NASA spacecraft already at Mars, both on the surface and in orbit, each of which is carrying out their own unique missions to reveal the mysteries of the planet’s history. Both the Opportunity and Curiosity rovers continue their science on the ground, while the agency’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and Mars Odyssey orbiter each continue to study the Red Planet from a bird’s eye view.

Launched on Nov. 18, 2013, MAVEN is specifically designed to explore Mars’ upper atmosphere over one Earth year to determine the role that escape of gas from the atmosphere to space has played in changing the climate throughout the planet’s history. Although the mission is expected to last for a year, NASA expects MAVEN to remain operational for up to a decade, as NASA’s spacecraft have a reputation for working well beyond their expected life spans.

We now know for certain that Mars was indeed once a world with liquid water on its surface, one of the key ingredients necessary for life as we know it, and some of that water still remains frozen under the surface. However, at some point the planet’s protective atmosphere withered away, exposing Mars’ surface to the extreme punishment of the solar winds and radiation, which effectively sterilized the planet’s surface.

When, how, and why this occurred are questions MAVEN is designed to answer. Where did the atmosphere and water go? Why did a planet that was once warm and wet become cold and dry? Water and carbon dioxide, which were both abundant on early Mars, could have been lost to space, or they could have seeped into the crust, forming H2O and CO2 bearing minerals. Evidence from research already being done on Mars shows that both processes have occurred, but scientists don’t understand their comparative importance.

That’s where MAVEN comes in. Measuring the current rate of escape to space and gathering enough information about the relevant processes to allow extrapolation backward in time will help MAVEN determine just how much of the Martian atmosphere has been lost over time. Although MAVEN will not be looking for life, or potential for life, it will determine whether microbes could have survived on Mars in the past by exploring the presence of water and atmosphere through Martian history.

According to Mitchell, the spacecraft is in excellent health as it enters the final stretch for Mars.

“Last month we performed a series of tests on the Electra telecom relay package, some of the Particles & Fields instruments from the University of California-Berkeley, the mass spectrometer from the Goddard Space Flight Center, and the spacecraft star trackers,” said Mitchell. “The team also did a second round of magnetometer calibrations. The calibration was conducted by rolling the spacecraft, using thrusters, about the three spacecraft axes.”

VIDEO: MAVEN, Exploring the Upper Atmosphere of Mars

A third Trajectory Correction Maneuver, or TCM-3, was scheduled for July 23 to adjust the “aim point” of MAVEN at its closest approach when it arrives, so that it can properly enter orbit around the planet. However, TCM-3 was cancelled because MAVEN’s flight path was so good it did not need it.

“We are tracking right where we want to be. So the next, and probably final, TCM is planned for September 12th,” added Mitchell.

A significant technical review on the MAVEN team’s readiness for the Mars Orbit Insertion event went very well last month, too, which included independent technical experts from the Goddard Space Flight Center, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Lockheed Martin, and other external aerospace consultants.

Although the review was aimed at making sure everything is good to go for MOI next month, it also focused on MAVEN’s role in the upcoming Comet C/2013 A1 Siding Spring encounter coming up this fall. The comet will come within 85,000 miles of the Red Planet on Oct. 19, and NASA’s fleet of robotic Mars explorers will be positioned with front row seats to study the comet by taking advantage of how close it comes to Mars (Siding Spring’s nucleus and Mars will be less than one-tenth the distance of any known previous Earthly comet flyby).

The comet’s nucleus, coma, and tail will all be studied in detail as it passes Mars, as well as the possible effects on the Martian atmosphere. MAVEN in particular will study gases coming off the comet’s nucleus into its coma as it is warmed by the Sun, while also looking for effects the comet flyby may have on the planet’s upper atmosphere. The spacecraft will also observe the comet as it travels through the solar wind.

“The team has made final decisions on how we are going to operate the spacecraft during the comet’s closest approach,” said Mitchell. “With safety as the highest priority, the plan is to take exciting science data of the comet and Mars’ atmospheric response a couple days before and after the comet’s closest approach on October 19th. On October 19th itself, we will go into a “hunker down” mode as the comet passes by the Mars vicinity.”

As the comet passes by Mars it will be throwing off material at about 35 miles per second. At such velocities even a strike from a half-millimeter-sized particle could cripple a spacecraft beyond saving, so it’s easy to understand why such an event would be of great concern to America’s fleet of Mars spacecraft. However, NASA’s modeling results indicate that the hazard to the spacecraft is not as bad as was originally believed.

“Three expert teams have modeled this comet for NASA and provided forecasts for its flyby of Mars,” explained Rich Zurek, chief scientist for the Mars Exploration Program at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “The hazard is not an impact of the comet nucleus, but the trail of debris coming from it. Using constraints provided by Earth-based observations, the modeling results indicate that the hazard is not as great as first anticipated. Mars will be right at the edge of the debris cloud, so it might encounter some of the particles — or it might not.”

According to the MAVEN Mission Facebook page, as of 8:00 p.m. EDT on Aug. 21 MAVEN was at a distance of 117,915,234 miles from Earth, with an Earth-centered velocity of 16.2 miles per second (or 58,338 mph) and a Sun-centered velocity of 13.8 miles per second (or 49,612 mph). The spacecraft is currently at a distance of 5,253,417 miles from Mars and 134,421,968 miles from the Sun. One-way light time to the MAVEN spacecraft from Earth is 10 minutes and 31 seconds, and all recent navigation solutions produce trajectory arrival predictions that ensure a successful transition to MAVEN’s required science orbit.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » MAVEN »