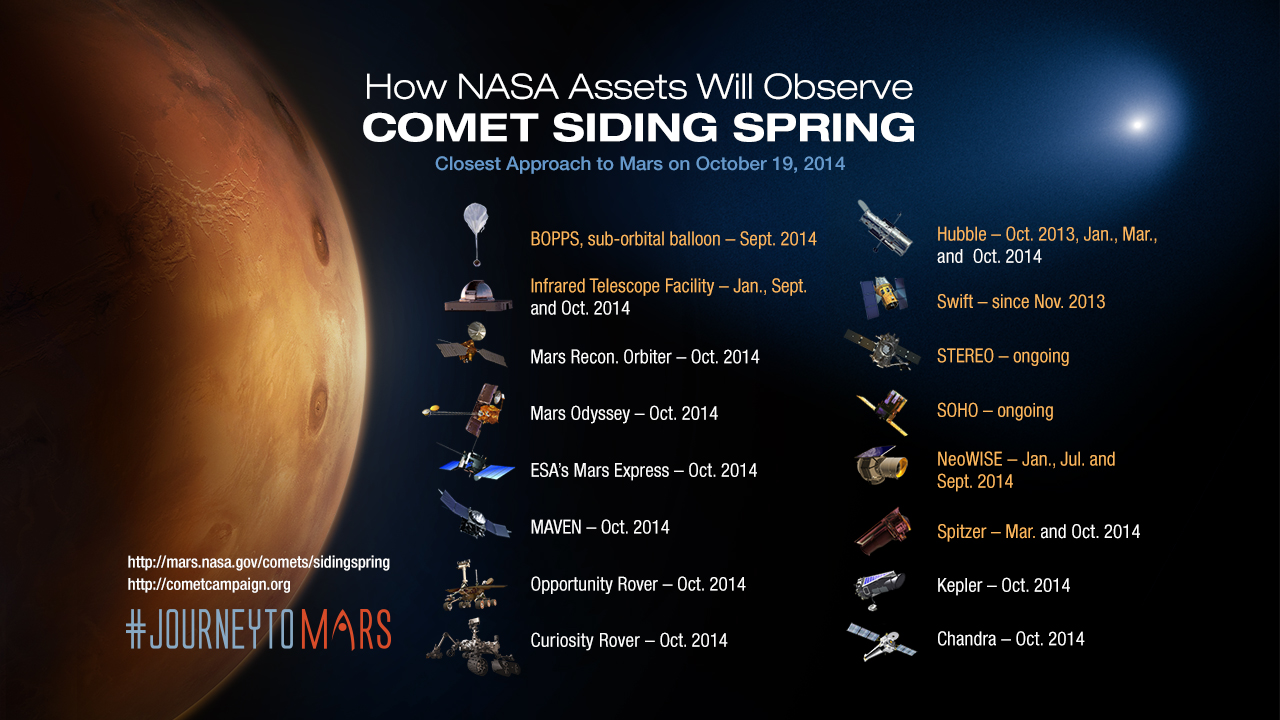

When Comet C/2013 A1 Siding Spring made its closest approach to Mars on Oct. 19, 2014, it gave researchers a once in a lifetime opportunity to obtain the first-ever up-close observations of such an event, courtesy of the many spacecraft both orbiting above and driving on the surface of the Red Planet. Although the long-term effects of the close encounter won’t be known for some time, observations made by three Mars orbiters have revealed that the immediate effects of the comet’s flyby caused significant temporary changes in the planet’s upper atmosphere.

Comet C/2013 came within just 87,000 miles of Mars at its closest approach, which is less than half the distance between Earth and our Moon and less than one-tenth the distance of any known comet flyby of Earth in recorded history. Knowing the significance of such a scientific opportunity NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) coordinated a well-orchestrated plan to safeguard their spacecraft and position them to gather as much data as possible, and today the space agency announced their initial findings from data collected by the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), and a radar instrument on ESA’s Mars Express spacecraft.

“This historic event allowed us to observe the details of this fast-moving Oort Cloud comet in a way never before possible using our existing Mars missions,” said Jim Green, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division at the agency’s Headquarters in Washington. “Observing the effects on Mars of the comet’s dust slamming into the upper atmosphere makes me very happy that we decided to put our spacecraft on the other side of Mars at the peak of the dust tail passage and out of harm’s way.”

When Siding Spring made its flyby of the Red Planet at 125,000 mph (or 56 km per sec), it showered dust and debris from its long tail all over Mars’ upper atmosphere, adding a temporary and very strong layer of ions to the electrically charged layer high above Mars, known as the ionosphere. Thanks to the observations made by the three mentioned spacecraft, scientists have—for the first time ever on any planet, including Earth—made a direct connection between the input of debris from a specific meteor shower and the formation of this kind of transient layer in a planet’s upper atmosphere.

While it’s very possible that some of the comet’s debris may have made it through the atmosphere and impacted the surface, most was vaporized high in the atmosphere, and had anyone been there to watch it they would have probably been treated to a spectacular meteor shower.

MAVEN, which only arrived at Mars less than two months ago, is specifically designed and developed to study the Martian atmosphere, and its remote-sensing Imaging Ultraviolet Spectrograph observed intense ultraviolet emission from magnesium and iron ions in the planet’s upper atmosphere in the aftermath of Siding Spring’s meteor shower. According to NASA, even the most intense meteor showers observed thus far on Earth over the years have never produced as strong a response; the emission dominated Mars’ ultraviolet spectrum for several hours after the comet’s flyby and then dissipated over the next 48 hours following the encounter.

The spacecraft also directly sampled and determined the composition of some of the comet dust Siding Spring rained down on Mars’ atmosphere, and analysis made by MAVEN’s Neutral Gas and Ion Mass Spectrometer detected eight different types of metal ions, including sodium, magnesium, and iron. In doing so, MAVEN now claims its place in history as having made the very first direct measurements of the composition of dust from an Oort Cloud comet.

ESA’s Mars Express orbiter put its joint U.S. and Italian Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionospheric Sounding (MARSIS) instrument to work as well, observing a huge increase in the density of electrons in Mars’ ionosphere from dust particles burning up in the atmosphere within hours following Siding Spring’s flyby.

NASA’s MRO spacecraft also detected the enhanced ionosphere through observations made with its Shallow Subsurface Radar (SHARAD) instrument, which provided scientists with smeared images by the passage of the radar signals through the temporary ion layer created by Siding Spring’s dust. The smearing tells researchers that the electron density of the ionosphere on the planet’s night side, where the observations were made, was five to 10 times higher than usual.

Studying the comet’s influence on Mars and its atmosphere was not the only goal, though; scientists also used the orbiters to study the comet itself, as such close encounters are few and far between. MRO’s High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera showed Siding Spring’s nucleus to be just 1.2 miles in size, which is smaller than what scientists had expected. and the same images also revealed the rotation period for the comet’s nucleus to be eight hours, which matched the preliminary observations made by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope prior to the encounter. The spacecraft’s Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument also looked for signs of any particular chemical constituents in the comet’s spectrum.

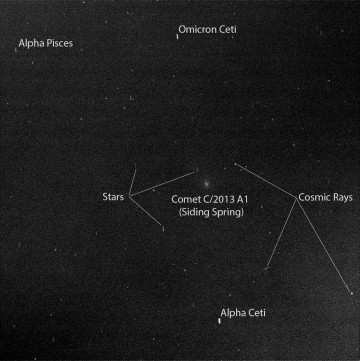

Both of NASA’s surface rovers, Opportunity and Curiosity, were positioned to photograph the comet as it passed as well, and although the comet is visible in Opportunity’s few images they leave much to be desired (Curiosity’s images barely show anything, if at all). However, the significance of observing a comet from the surface of another world is something worth celebrating in its own right, because never in human history has that ever been done.

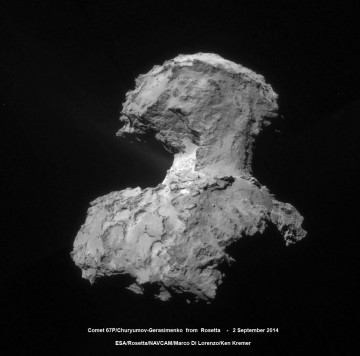

ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft is currently orbiting comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, having recently arrived after a decade-long journey from Earth, and on Nov. 12 the spacecraft will deploy its lander, Philae, to land on the surface of the comet in an area named Agilkia. The landing will mark the first time in human history that a spacecraft has landed on the surface of a comet and will help scientists to reveal the secrets of these frozen time capsules who still hold the raw materials from which the Solar System was birthed.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » MAVEN »

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Comet’s Close Encounter With Mars Yields New Insights Never Before Seen | Unidentified Aerial Phenomenon