Having circled hundreds of miles above Earth, a pair of NASA spacefarers with a personal affinity for the word hundred were this weekend inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame (AHOF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Four-time flier Brian Duffy, who commanded the shuttle’s hundredth voyage in October 2000, and five-time veteran Scott Parazynski, who flew the mission actually designated “STS-100” in spring 2001, were honored by their peers and the public for making significant contributions to the space program. Over the course of their astronaut careers, Duffy and Parazynski totaled nine shuttle missions between March 1992 and November 2007, featuring rendezvous, docking, spacewalking, scientific research, visiting Russia’s Mir space station, and building the International Space Station (ISS). All told, the pair flew three times apiece on shuttles Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour and spent close to a hundred days—98.5 days, to be exact—in space.

Announced back in February, Duffy and Parazynski represent the 92nd and 93rd astronauts to join the AHOF. “These men embody the courage, sacrifice and long-held commitment to furthering space exploration that is at the heart of the NASA mission,” said four-time shuttle veteran Dan Brandenstein, a 2003 AHOF inductee and current board chairman of the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation (ASF), which oversees the induction selection process. “I am truly honored to name them as the newest inductees into the United States Astronaut Hall of Fame.”

Since the first inductions—of the “Original Seven” Mercury astronauts, including posthumous recognition to Apollo 1 Commander Virgil “Gus” Grissom, back in May 1990—veteran spacefarers from Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo and the Space Shuttle Program have joined the illustrious ranks of the AHOF. Under eligibility rules, U.S. astronauts are selected by a committee of existing inductees, as well as former NASA officials, flight directors, historians, and journalists. Each successful inductee must have completed his or her first spaceflight at least 17 years prior to induction and must have orbited Earth on at least one occasion. With the Mercury Seven having been induced first, the next two classes of inductees in 1993 and 1997 were dominated by Gemini, Apollo, and Skylab veterans, with the first shuttle-era astronauts joining its ranks in the 2001 selection.

Over the years, these selections have included such luminaries as America’s first spacewalker and the world’s first Moonwalker, Ed White and Neil Armstrong, both of whom were inducted in 1993, together with former NASA Administrator Dick Truly, former NASA Deputy Administrator Fred Gregory, and current NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden. The majority of NASA’s former chief astronauts—from Al Shepard to John Young, from Brandenstein to Robert “Hoot” Gibson, and from Bob Cabana to Charlie Precourt—have also been admitted. Last year, the AHOF ranks were further boosted by shuttle veterans Rhea Seddon, John Grunsfeld, Kent Rominger, and Steve Lindsey. Having commanded the final voyage of Shuttle Discovery, four years earlier, Lindsey become the most-recently-flown inductee to enter the AHOF.

Attended by more than 400 guests, 2016’s inductions were made during a nostalgic weekend, which began Friday evening with a glittering Induction Gala, underneath the monumental Saturn V. Measuring 363 feet (110 meters) long, the largest rocket ever brought to operational status provided a fitting backdrop, accompanied by the crew patches of some of the greatest space missions ever undertaken. For AmericaSpace’s Talia Landman, who attended Friday’s event, it was a time to be “inspired by those who have dedicated their lives to furthering America’s space program and inspiring the next generation of space explorers.” This was followed, on Saturday, by the actual inductions of Duffy and Parazynski, which brought the membership of the AHOF to 93.

Duffy was selected as an astronaut candidate in June 1985, only months before the Challenger tragedy, after previously flying the F-15 Eagle as an Air Force fighter and test pilot. On many occasions during his career, he had flown at Mach 2, and had always considered that to be pretty fast, but during his first shuttle launch on STS-45 in March 1992 “we blew through Mach 2 in nothing flat and we still had a long way to go to accelerate.” From his first launch, Duffy clearly remembered the ethereal instant when the three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) shut down and the entire cabin went deathly silent. “You go from the most violent place you’ve ever been in your life,” he told the NASA oral historian, “to the most peaceful place you’ve ever been in your life, in a couple of seconds.”

Returning through Earth’s atmosphere, Duffy was struck by the carnation-pink glow of re-entry and also by the peculiar sensation of moving from normal terrestrial gravity to microgravity and back again. “I actually had to put my hand on the glare shield,” he reflected later, “and hold my torso up to keep it from slumping down and forward during the entry.” He had already been assigned to his second mission, a couple of weeks before his first launch. “Jeez, I sure hope I like this,” he told himself, “because I just signed up for two of them!” On his second flight, STS-57 in June 1993, he narrowly missed launching on his 40th birthday, but the mission spectacularly trialed the new Spacehab research module and recovered the European Retrievable Carrier (EURECA) from orbit.

At one point during STS-57, Duffy was on the shuttle’s flight deck, as two of his crewmates performed an EVA. “All of a sudden, it was as if somebody took the orbiter and hit it with a bulldozer,” he told the NASA oral historian. “The whole vehicle shook. It got quiet on the flight deck and we thought maybe we were hit by something.” However, no visible damage or objects were apparent and Mission Control saw nothing amiss with their data. It later became apparent that residual forces within the Spacehab tunnel adapter struts had released, “ringing” the entire vehicle and giving Duffy and his crewmates an instant of wide-eyed shock.

His third mission, STS-72 in January 1996, fell ten years to the month since the loss of Challenger. Duffy commanded a crew of five to retrieve Japan’s Space Flyer Unit (SFU), deploy and recover a SPARTAN free-flying satellite and perform a pair of EVAs, ahead of International Space Station (ISS) assembly. Two years later, he was assigned to command STS-92, which flew—after many delays—in October 2000, becoming the 100th shuttle mission. Duffy and his crew rendezvoused and docked with the fledgling ISS and supported four EVAs to install the Z-1 truss element and the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-3, as the on-orbit construction of the outpost entered full swing.

Speaking at his induction ceremony—fittingly, beneath Space Shuttle Atlantis, which he flew twice during his career—Duffy remembered telling his wife, Jan, the news that he would become an astronaut. His wife, unsurprisingly, was excited, as were their two children, including their son, who was two years old at the time. After cheering for a few minutes that “Daddy’s going to be an astronaut!”, their son piped up with “What’s an astronaut?” Duffy expressed his appreciation for “the absolute commitment of tens of thousands of people” who enabled the shuttles to undertake their remarkable journeys, reflecting that on the final day of each of mission he and his crews wiped every surface to ensure that they returned the vehicle as clean as possible to KSC. “We didn’t want them to think that we had really trashed it,” he said to a roll of laughter in the audience.

“What an incredible, charmed life I’ve lived to have this opportunity to live out my boyhood dreams” were among the words of reflection from this weekend’s second inductee, Scott Parazynski. He was selected as an astronaut in March 1992, the same month as Duffy made his first mission. The son of an Apollo-era Boeing engineer, with an admittedly “nomadic” upbringing, Parazynski was schooled in Dakar, Beirut, Tehran, and Athens, but came out with a sense that life’s greatest lessons actually came outside the classroom. After qualifying as a medical doctor, he competed on the U.S. Development Luge Team, ranking within the Top Ten competitors in the 1988 Olympic Trials.

Parazynski first flew in November 1994, aboard Atlantis—the very vehicle which hung above his head on Saturday’s induction ceremony—and also completed his second mission, in the fall of 1997, aboard the “middle child” of NASA’s shuttle fleet. Betwixt these voyages, he might have embarked on a multi-month voyage to the Mir space station, had it not been for a strange event which saw him declared “too tall” to safely fit aboard the descent module of Russia’s Soyuz. Together with fellow astronaut Wendy Lawrence, who was similarly removed from Soyuz training on account of being “too short,” the pair created self-deprecating name tags for themselves: Too Tall and Too Short.

During his second mission, STS-86, Parazynski performed his first career EVA with Russian cosmonaut Vladimir Titov, outside Mir. This marked the first occasion that a non-U.S. citizen had performed a spacewalk from a U.S. spacecraft. At one stage, they were asked to hold off returning to the airlock, in order to complete a task, to which Parazynski joked: “I think you could talk us into that!” A year later, in October 1998, he flew aboard STS-95 with Sen. John Glenn, on a mission that he described as like playing baseball with Babe Ruth or climbing Mount Everest with Sir Edmund Hillary. “This, for an astronaut, is about as exciting as it gets,” he said. And Everest was an interesting remark, for in May 2009, shortly after he departed NASA, Parazynski became the first U.S. astronaut to successfully summit the tallest mountain on Earth.

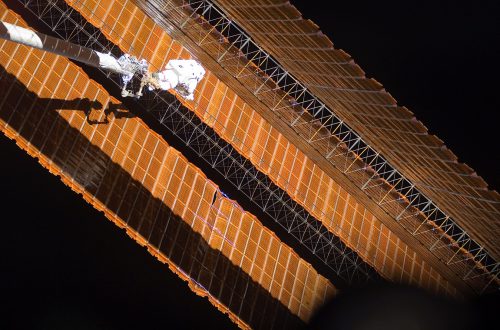

Following STS-95, he went on to support six more EVAs on two ISS construction missions: STS-100 in early 2001, which installed Canadarm2—the Space Station Remote Manipulator System (SSRMS), which continues to support spacewalkers and the arrivals and departures of unpiloted visiting vehicles—and STS-120 in the fall of 2007, which delivered the Harmony node. On STS-120, Parazynski became only the second U.S. astronaut, after Bob Curbeam, to perform as many as four EVAs on a single shuttle flight. The last of these EVAs was particularly memorable: for Parazynski successfully installed cufflink-like ties across the 15-foot (4.5-meter) width of a torn solar array blanket on the station’s P-6 truss.

“To receive this great recognition, not as an individual, but on behalf of literally the thousands of people who’ve touched my professional career,” said Parazynski, pausing to choke back a tear of emotion. He described the NASA/contractor workforce as “brilliant, resourceful, creative, passionate,” adding that he considered it “extraordinary” to be able to grow up in a nation which “dreams big, but then has the resolve to fulfil those challenges.” With a nod to future generations of astronauts, Parazynski told the audience that he saw an “extremely bright” future for the U.S. space program.

“The Astronaut Hall of Fame really has nothing to do with Brian or myself here today, or even the space pioneers in front of me,” Parazynski concluded. “The Astronaut Hall of Fame was really created by the Mercury Seven astronauts, to use their notoriety to help inspire and support financially our best and brightest in STEM fields.” Indeed, since the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation was formed, three decades ago, over $4 million has been awarded in merit-based scholarships to more than 400 brilliant students in the fields of the sciences, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

With thanks to my AmericaSpace colleagues Talia Landman and Emily Carney for kindly providing images and information in support of this article.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace