The New Horizons mission to Pluto has been nothing less than incredible, giving us our first close-up views of this enigmatic dwarf planet and its moons. But the show isn’t over yet, as the New Horizons team is now planning for its next encounter with another Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) in 2019. But even before then, the spacecraft has been busy observing other smaller objects, and has now collected the first science data on one of them, called 1994 JR1.

New Horizons has now observed this tiny world, only 90 miles (145 kilometers) wide, twice so far. Like Pluto, it inhabits the Kuiper Belt in the far outer reaches of the Solar System, more than 3 billion miles (5 billion kilometers) from the Sun. It is only one of thousands of such objects, but by studying it, scientists can learn more about KBOs in general, including larger ones such as Pluto.

When images were taken by New Horizons on April 7-8, 1994 JR1 was about 69 million miles (111 million kilometers) away from the spacecraft. That is a long way away, of course, but still much, much closer than it is to Earth. Previously, New Horizons had seen this object from a distance of 170 million miles (280 million kilometers).

“Combining the November 2015 and April 2016 observations allows us to pinpoint the location of JR1 to within 1,000 kilometers (about 600 miles), far better than any small KBO,” said Simon Porter, a New Horizons science team member from Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colo. Being able to more accurately plot the orbit of 1994 JR1 also allowed the science team to disprove a theory that the KBO may be a quasi-moon of Pluto. Now we know it isn’t, but that still leaves five moons for Pluto, some of which are very small, like asteroids.

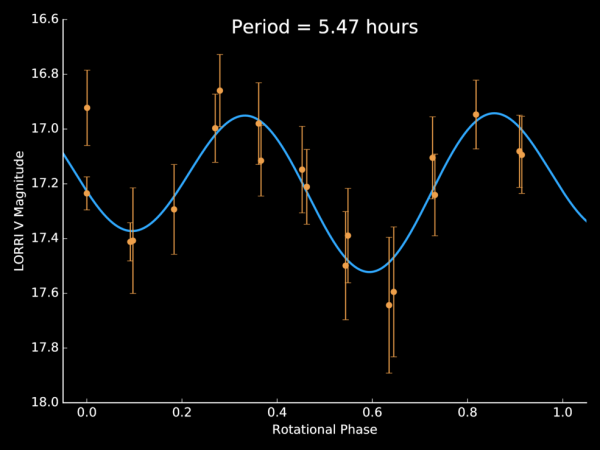

The observations are close enough that the mission team can also determine the rotation period of this KBO, which is once every 5.4 hours. “That’s relatively fast for a KBO,” said John Spencer, also from SwRI. “This is all part of the excitement of exploring new places and seeing things never seen before.”

Just being able to obtain these images and other data is exciting for scientists, because it wouldn’t be possible from Earth. Only a spacecraft in that distant region of space could accomplish this. Even Pluto, much larger than most other KBOs such as this one, only appeared as a tiny dot of light in the best telescopes, with just vague hints of surface features discernible. But New Horizons has revolutionized our view of the Pluto system, and now is ready to do the same with other KBOs. Scientists expect to get closer looks at possibly 20 more such KBOs over the next few years, as long as the extended mission for New Horizons gets approved and budgeted. On Jan. 1, 2019, the spacecraft is scheduled to make a close flyby of another KBO, known as 2014 MU69.

On Nov. 4, 2015, New Horizons conducted the final course correction needed to put it on the trajectory for a close flyby of 2014 MU69.

“This is another milestone in the life of an already successful mission that’s returning exciting new data every day,” said Curt Niebur, New Horizons program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “These course adjustments preserve the option of studying an even more distant object in the future, as New Horizons continues its remarkable journey.”

Four course corrections have been completed successfully, starting on Oct. 22, 2015. The fourth maneuver was started at approximately 1:15 p.m. EST on Wednesday, Nov. 4, and continued for just under 20 minutes.

“The performance of each maneuver was spot on,” said APL’s Gabe Rogers, who is the New Horizons systems engineer and guidance and control lead.

New Horizons is now ready to continue exploring the Kuiper Belt region, pending approval of the mission extension, and the spacecraft itself is still in excellent health.

“New Horizons is healthy and now on course to make the first exploration of a building block of small planets like Pluto, and we’re excited to propose its exploration to NASA,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of SwRI.

The new mission extension proposal, called Kuiper Belt Extended Mission (KEM), has been formally submitted to NASA for approval, as reported previously on AmericaSpace. The main objectives include:

- Make distant flyby observations of about 20 other KBOs during 2016-2020, determining their shapes, satellite populations, and surface properties – something no other mission or ground-based telescope can.

- Make sensitive searches for rings around a wide variety of KBOs during 2016-2020.

- Conduct a heliospheric transect of the Kuiper Belt, making nearly continuous plasma, dust, and neutral gas observations from 2016 to 2021, when the spacecraft reaches 50 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun.

- Potentially conduct astrophysical cruise science in 2020 and 2021, after the MU69 flyby, if NASA desires.

The highlight will be the flyby of 2014 MU69, which New Horizons will pass at a distance of only about 1,900 miles (3,000 kilometers), four times closer than the Pluto flyby. 2014 MU69 is much smaller than Pluto, only about 13 to 25 miles (21 to 40 kilometers) across, which is similar in size to Mars’ two tiny moons, Phobos and Deimos. 2014 MU69 was discovered in 2014 by the Hubble Space Telescope, as part of a search for other KBOs.

“Even as the New Horizon’s spacecraft speeds away from Pluto out into the Kuiper Belt, and the data from the exciting encounter with this new world is being streamed back to Earth, we are looking outward to the next destination for this intrepid explorer,” said John Grunsfeld, chief of the NASA Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “While discussions whether to approve this extended mission will take place in the larger context of the planetary science portfolio, we expect it to be much less expensive than the prime mission while still providing new and exciting science.”

The Kuiper Belt, a vast region of small bodies out past Neptune, with Pluto the largest, is similar to the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and it still almost completely unexplored. As noted by Stern:

“The Kuiper Belt is a rich scientific frontier. Its exploration has important implications for better understanding comets, the origin of small planets, the Solar System as a whole, the solar nebula, and dusty Kuiper Belt-like disks around other stars, as well as for studying primitive material from our own Solar System’s planet formation era. The exploration of the Kuiper Belt and KBOs like MU69 by New Horizons would transform Kuiper Belt and KBO science from a purely astronomical pursuit, as it is today, to a geological and geophysical pursuit.”

There is also strong support for the exploration of the Kuiper Belt by New Horizons from NASA’s own Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) and Small Bodies Assessment Group (SBAG). In April 2014, these two advisory committees stated that “SBAG and OPAG are united in affirmation of the tremendous scientific value of exploring a primitive KBO in situ, where it remains essentially unaltered since the time of planetesimal formation,” and that ‘The scientific bounty of a spacecraft encounter with a primitive KBO is realizable in our lifetimes, but only with New Horizons … No other mission currently in flight, in build, or in design will reach the Kuiper Belt.”

Like other asteroids and comets, these objects are leftover relics from the formation of the early Solar System. By studying them in more detail, scientists will be able to learn more about just how our Solar System originated and evolved, as well as thousands of other planetary systems now being discovered by telescopes such as Kepler. Pluto itself has turned out to be a fascinating little world, with vast plains of nitrogen ice, glaciers, mountains of solid water ice, a bluish, layered atmosphere, and ancient rivers and lakes of liquid nitrogen. What is else is waiting to be discovered in the unexplored region beyond?

Follow our New Horizons mission page for regular updates.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » New Horizons »

KEM must be approved. The scientific return is too great to pass up. It’s a no-brainer.

“Potentially conduct astrophysical cruise science in 2020 and 2021, after the MU69 flyby, if NASA desires.”

Yep. The New Horizons ‘Kuiper Belt Extended Mission’ makes a lot of good sense.

In a similar mode to Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 that were launched in 1977 and currently continue to observe the outer Solar System, one may wonder if New Horizons could last longer than 2021 and provide useful data for several more decades.

Concerning New Horizons:

“2026 Expected end of the mission, based on RTG plutonium decay. Heliosphere data collection expected to be intermittent if instrument power sharing is required.”

And, “2038 New Horizons will be 100 AU from the Sun. If still functioning, the probe will explore the outer heliosphere along with the Voyager spacecraft.” From: ‘New Horizons’

At: Wikipedia

Concerning Voyager 1 and Voyager 2: “Both spacecraft also have adequate electrical power and attitude control propellant to continue operating until around 2025, after which there may not be available electrical power to support science instrument operation.” From: ‘Voyager program’ At: Wikipedia

Note also:

“Scientists from the University of New Hampshire and colleagues answer the question of why NASA’s Voyager 1, when it became the first probe to enter interstellar space in mid-2012, observed a magnetic field that was inconsistent with that derived from other spacecraft observations, in a study published today in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.”

From: ‘Study solves mysteries of Voyager 1’s journey into interstellar space’ November 16, 2015 At: http://www.satprnews.com/2015/11/16/study-solves-mysteries-of-voyager-1s-journey-into-interstellar-space/

James, perfect analysis and reasoning! Thank you!