With a mission patch artwork that declares “Always vigilant, always watching”, a second pair of Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP) satellites roared aloft atop a never-before-used United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V on Friday.

Liftoff of the Mighty Atlas—flying in its unique “511” configuration, with a 17.7-foot (5.4-meter) Short Payload Fairing (SPF), a single solid-fueled rocket booster and a single-engine Centaur upper stage—occurred from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., at 2 p.m. EST. It marked the 75th Atlas V mission to originate from the Cape and kicked off an ambitious 2022 for ULA, which hopes to launch more than 12 times, a impressive flight-rate tempo unseen since 2016.

The meteorological outlook for both Friday’s primary launch attempt and a backup opportunity on Saturday were generally favorable, initially hovering around 60-70 percent favorable, thanks to what the 45th Weather Squadron at Patrick Space Force Base called an “increasingly complex” picture as the weekend neared. This forecast was driven by the predicted approach of a cold front and the possibility of an area of low pressure evolving over the Gulf of Mexico, bringing with it an elevated likelihood of showers, thunderstorms and a violation of the Cumulus Cloud Rule and Thick Cloud Layer Rule. However, as the countdown clock ticked inside T-1 hour, the forecast improved to 90 percent, with only scattered low-level clouds and broken high-level clouds.

Photo credit: Jeff Seibert/AmericaSpace

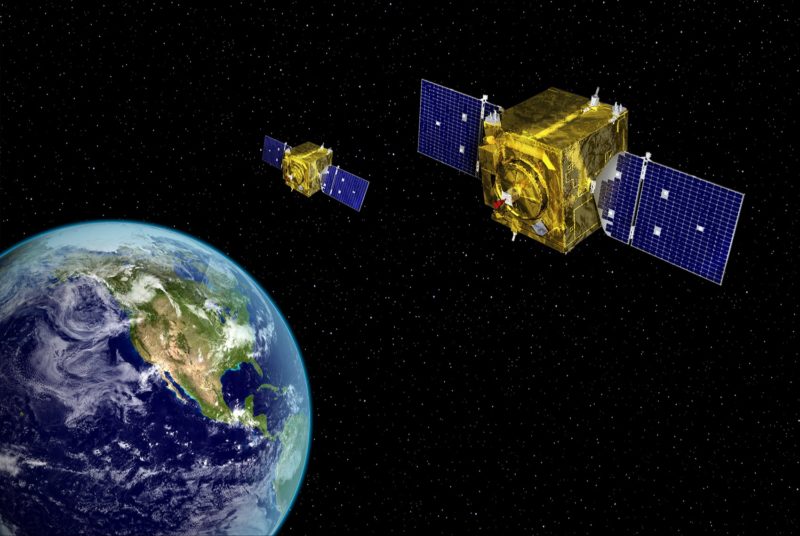

Primary payload for this mission is USSF-8, flying on behalf of the U.S. Space Force and consisting of the fifth and sixth in a constellation of GSSAP satellites which the Atlas V injected directly into geosynchronous orbit, some 22,600 miles (35,900 kilometers) in altitude. GSSAP-5 and GSSAP-6 follow on the heels of two previous pairs of GSSAP birds which rode ULA Delta IV Medium+ rockets in July 2014 and August 2016.

Initially built by Orbital Sciences Corp.—and now Northrop Grumman Corp.—they are based upon the GEOStar-1 “bus”, specially optimized for a range of defense and civilian missions from weather and Earth observations to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance and from navigation, positioning and timing to tactical communications and reportedly capable of supporting payload masses up to 330 pounds (150 kilograms).

And the specific remit of GSSAP sits squarely within the Space Situational Awareness (SSA) arena. They are designed to support U.S. Strategic Command space surveillance operations as a dedicated Space Surveillance Network (SSN) sensor, as well as providing assistance for the Joint Functional Component Command for Space (JFCC-Space) as it more accurately tracks and characterizes human-made objects in orbit.

The GSSAP satellites drift above and below the Geosynchronous Earth Orbit (GEO) “belt” and utilize advanced electro-optical sensors to observe other objects. This data is expected to enhance the abilities of the Space Force to understand the geosynchronous environment and develop new safety systems, including collision-avoidance mechanisms. They also have the capacity to execute Rendezvous and Proximity Operations (RPO), maneuvering closely to resident space “objects of interest” to resolve anomalies or undertake enhanced surveillance.

In March 2014, then-head of Air Force Space Command Gen. William Shelton called GSSAP a “neighborhood watch” system for U.S. geosynchronous satellites. “GSSAP will produce a significant improvement in space object surveillance, not only for better collision avoidance, but also for detecting threats,” the general said. “GSSAP will bolster our ability to discern when adversaries attempt to avoid detection and to discover capabilities they may have which might be harmful to our critical assets at these higher altitudes.”

Two such assets are the Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) fleet of military communications satellites—the most recent of which launched in March 2020 and completed on-orbit testing the following September—and the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS), whose fifth geosynchronous-orbiting member flew last May. “One cheap shot against the AEHF constellation would be devastating,” Gen. Shelton noted. “Similarly, with our Space-Based Infrared System, one cheap shot creates a hole in our environment.”

Following the emplacement of the first four GSSAP satellites in orbit, in March 2018 the Air Force selected ULA to launch GSSAP-5 and GSSAP-6 as part of a $351.8 million contract for two Air Force Space Command (AFSPC) missions originally designated AFSPC-8 and AFSPC-12.

“The first four GSSAP satellites have performed remarkably well,” said Lt. Gen. Stephen N. Whiting of the Space Force, who currently commands Space Operations Command at Peterson Space Force Base, Colo. “These next two satellites will add to that capability and enable us to understand more completely things that occur in the geosynchronous orbit. It’s a key piece in the puzzle for space domain awareness.”

After the redesignation of Air Force Space Command and the formal creation of the Space Force in December 2019, the missions henceforth became known as USSF-8 and USSF-12. Current plans are for USSF-12—a Wide-Field of View (WFOV) experimental early-warning satellite—to ride an Atlas V from the Cape in March.

In October 2020, the 107-foot-long (32-meter) Atlas V Common Core Booster (CCB) and the 41-foot-long (12.6-meter) Centaur upper stage for the USSF-8 mission arrived at the Cape, via ULA’s RocketShip vessel after a water-borne journey from the factory in Decatur, Ala. At the time, launch was targeted for the spring of the following year, but multiple delays stacked up against ULA’s 2021 manifest, pushing USSF-8 inexorably into the summer and fall, then eventually into January 2022.

After arrival at the Cape, the Atlas V CCB underwent receiving checks and horizontal processing, before moving into the 30-story Vertical Integration Facility (VIF) at SLC-41 for installation of its inter-stage adapter, payload fairing base segments and support ring.

The Launch Vehicle On Stand (LVOS) campaign—the effort to assemble the full rocket in the VIF—got underway in mid-December, when the Centaur and a single Graphite Epoxy Motor (GEM)-63 solid-fueled rocket booster were mated to the stack.

As previously outlined by AmericaSpace, the GEM-63 is an Atlas V version of a new strap-on booster destined for ULA’s Vulcan-Centaur heavylifter. Numerically designated to identify its 63-inch-wide (1.6-meter) casing, the GEM-63 was built by Northrop Grumman and stands 65.9 feet (20.1 meters) tall. On 18 December, the Atlas V CCB was hoisted atop the Mobile Launch Platform (MLP) in the VIF, followed two days later by the attachment of the Centaur and the single GEM-63.

USSF-8 marked the first (and possibly last) outing of the “511” variant of the Atlas V, the presence of whose singular strap-on booster created an unusual “sideways-flying” perspective as it “slid” upwards from the pad. Steering actuators on the Atlas V’s RD-180 engine counteracted the asymmetrical thrust from the GEM-63 to ensure that the rocket flew straight and true, but it undoubtedly offered a disconcerting sight for spectators.

ULA CEO Tory Bruno has previously noted that his nickname for the 511 is “Big Slider”. It can lift up to 24,250 pounds (11,000 kilograms) of payload to low-Earth orbit and up to 11,570 pounds (5,250 kilograms) to geosynchronous altitude.

Following the Christmas and New Year holiday downtime, the USSF-8 payload—encapsulated within its Short Payload Fairing (SPF)—was transferred to the VIF on 10 January and mounted atop the stack. This raised the total height of the Atlas V to 196 feet (59.7 meters).

On Wednesday, ULA Launch Director Eric Richards wrapped up the Launch Readiness Review (LRR) and teams signed the Launch Readiness Certificate to confirm their preparedness to support the USSF-8 launch. Rollout from the VIF to the pad, covering a distance of a quarter-mile (400 meters), occurred on Thursday and the Atlas V stack was confirmed as “hard-down” on the pad pedestals at 11:19 a.m. EST. She was then carefully centered and propellant umbilicals and electrical and data connections were established. The track mobiles from the MLP were removed and fueling operations late Thursday afternoon.

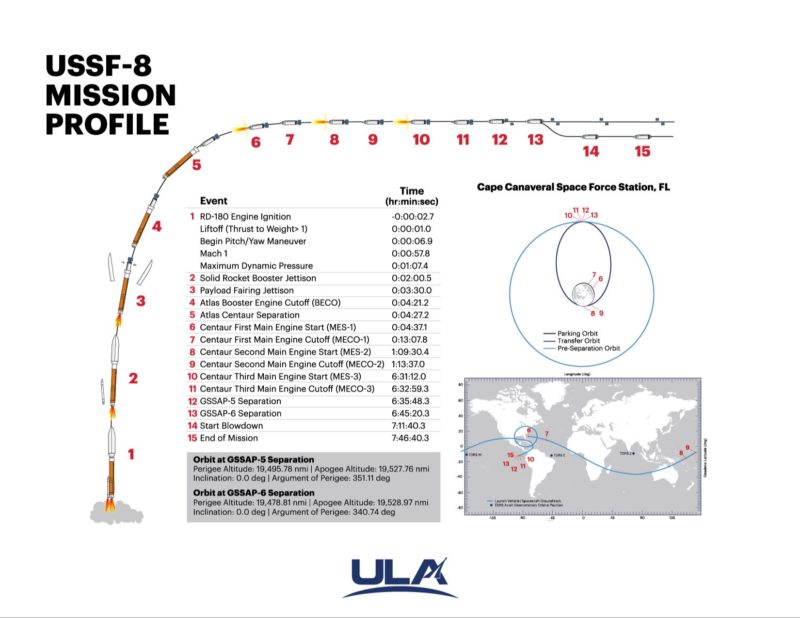

At the instant of liftoff, the dual nozzles of the RD-180 engine and the single GEM-63 generated a thrust of 1.2 million pounds (544,000 kilograms) to push the stack uphill. The Atlas V exceeded the speed of sound at 58 seconds into the climb and after exhausting its propellant supply the GEM-63 was discarded at two minutes.

Next came the jettison of the two halves of the SPF at 3.5 minutes after launch, exposing the GSSAP twins to the harsh space environment for the first time. And a minute thereafter, the RD-180 itself shut down as planned and the CCB was discarded.

This set up the proper conditions for a 6.5-hour, three-burn “ballet” by the Centaur to lift the payload to geosynchronous altitude. The first pair of burns—each running for about nine minutes apiece—served to circularize the vehicle in a stable Earth-parking orbit, before the third burn was set to move the GSSAP twins towards the geosynchronous transfer orbit. GSSAP-5 separation was planned for six hours and 35 minutes after launch, followed by GSSAP-6 about ten minutes later.

Today’s launch of USSF-8 and the GSSAP-5 and GSSAP-6 satellites marks the 75th mission of the Atlas V since the rocket entered service, way back in August 2002. All told, the fleet has launched a multitude of commercial, military and U.S. Government communications and Earth-imaging satellites and dozens of classified reconnaissance, intelligence and surveillance platforms for the National Reconnaissance Office and the Space Force. Four ISS-bound spacecraft—including three Northrop Grumman-built Cygnus cargo ships and the first CST-100 Starliner—also headed to orbit atop the Atlas V.

Added to that list, Atlas Vs originating from the Space Coast set the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) and the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers on the first legs of their respective treks out to the Red Planet. Our first exploratory foray to distant Pluto, the New Horizons spacecraft, was launched back in January 2006 and reached its destination 9.5 years later.

So too was the first solar-powered mission to Jupiter—Juno—which reached the Solar System’s largest planet in July 2016 to begin a comprehensive survey of the Jovian environment. Not to be outdone, Atlas Vs have launched a pair of major missions to explore the Sun, most recently 2020’s Solar Orbiter, as well as the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security-Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) and Lucy to explore some of the most ancient and pristine objects in the Sun’s realm.

With its first mission of 2022 thus complete, ULA can look toward an ambitious manifest for the remainder of the year. With a single Delta IV Heavy expected to launch the highly classified NROL-91 payload out of Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif., on behalf of the National Reconnaissance Office, the bulk of the action will center upon the Cape, the Atlas V and the next-generation Vulcan-Centaur.

Launch dates for the inaugural Vulcan missions have yet to be formally determined, although the first will deliver the Peregrine lander to the Moon’s surface and the second will lift Sierra Nevada Corp.’s first Dream Chaser cargo ship to the International Space Station (ISS).

Coming up in the Atlas V sphere of operations, SLC-41 will be a busy place in 2022, with the next Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES-T) set to fly for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in March. The Lockheed Martin-built satellite arrived in Florida last November for final processing, followed by the Atlas V and Centaur hardware a few days later. And on 18 January, Northrop Grumman announced that its GEM-63 boosters for the GOES-T mission were packed up and “on the road”, bound for the Cape.

Following GOES-T, the highly secretive USSF-12 is targeted to ride an Atlas V 551—the fleet’s most powerful variant—later this spring. Others include the classified USSF-51 and NROL-107 “Silent Barker” missions, the sixth geosynchronous-orbiting SBIRS, a pair of commercial communications satellites and the many-times-delayed second Orbital Flight Test (OFT-2) and the astronaut-carrying Crew Flight Test (CFT) of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner to the space station. And a single Atlas V mission from Vandenberg will deliver the second Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS) spacecraft to orbit.

3 Comments

3 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:ULA’s Mighty Atlas Launches Long-Delayed GOES-T Geostationary Earth-Watcher – AmericaSpace

Pingback:Mighty Atlas Launches USSF-12 Mission for Space Force, Department of Defense - AmericaSpace

Pingback:ULA Readies Mighty Atlas for 4 August Launch of Last SBIRS GEO Satellite - AmericaSpace