Setting aside the enormity of the fact that STS-26 would be the first shuttle voyage after a major disaster, the mission was relatively straightforward—a “vanilla flight”—since it would be just four days long and feature the deployment of the third Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-C) atop an Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster to replace the one lost aboard Challenger. Rick Hauck admitted that it would be “the safest flight we’ve flown,” but this did not prevent the space agency’s senior leadership from exaggerating its significance. STS-26 was a hugely important milestone, but for the jokers in the astronaut office, and particularly the crew of STS-27, it offered an opportunity for humour.

One evening, Hauck’s crew were present at a fundraising event for a Challenger charity at the Wortham Center in Houston. At its conclusion, the MC brought a young girl onto the stage to sing Lee Greenwood’s “I’m Proud To Be An American,” and the STS-26 crew was introduced. “At this cue,” wrote STS-27 Mission Specialist Mike Mullane, “the orchestra pit platform began a slow rise. Artificial smoke swirled about it and the spotlights flashed through the vapour. And there, to the astonishment of every astronaut, were Rick Hauck and Dick Covey. They stood like carvings on Mount Rushmore: chins jutted out, chests puffed up, arms rigidly at their sides, steely eyes straight ahead.”

Shortly thereafter, the crew of STS-27—Robert “Hoot” Gibson, Guy Gardner, Mike Mullane, Jerry Ross, and Bill Shepherd—plotted their revenge. Two days later, at the astronaut office’s Monday morning meeting, Gibson was asked if he had any STS-27 issues to discuss. At this stage, the plan went into action. Jerry Ross pressed a button on a boom box, triggering Greenwood’s track, whereupon Mullane and Shepherd set off a pair of CO2 fire extinguishers to create a smoky effect, and Gibson and Gardner, who had clipped ties onto their flight suits, slowly rose from their chairs in an outrageous parody of Hauck and Covey. Watching the proceedings was fellow astronaut Kathy Sullivan. “They rise, all the way, until they’re standing straight and tall,” she said in her NASA oral history. “Then Mullane shuts off the boom box, the fire extinguisher goes out, they sit back down and Hoot says calmly, ‘No, we don’t have anything!’” The office exploded with laughter.

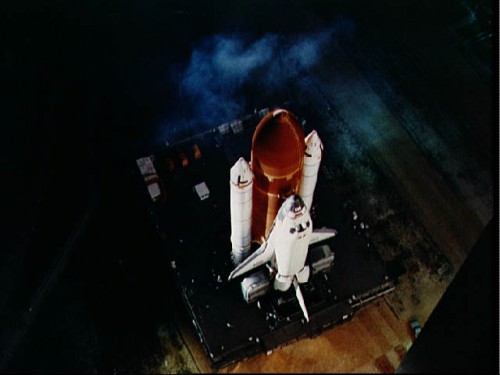

On Independence Day, 4 July 1988, at a darkened Kennedy Space Center, the complete STS-26 stack—Discovery, her External Tank, and twin SRBs—left the cavernous Vehicle Assembly Building and made the slow roll to Pad 39B. Dave Hilmers was in attendance and spoke to the assembled crowd of NASA employees who had worked tirelessly for this day to come. “For over two years now,” he said, “each one of us here, tonight, has had a dream, that one day a shuttle would once again make its way to the launch pad to launch Americans into space.” That launch had already slipped from February to June to August and, now, to September. Shortly before rollout, a tiny leak, deep within Discovery’s left-hand Orbital Manoeuvring System pod, was discovered, but was fixed on the pad. Then, on 10 August, after one false start, the orbiter’s three main engines were test-fired for 22 seconds, and on the 29th TDRS-C and its attached IUS arrived at the pad and were installed into the payload bay. When STS-26 finally set off on 29 September, no fewer than 32 months would have elapsed since the loss of Challenger.

The day itself was a calm, warm one, which Hauck remembered lucidly, even many years later. Radiosonde balloon soundings had highlighted an upper-level wind shear which might pose a constraint to the launch, and the astronauts left the Operations and Checkout Building for what they assumed would be a fruitless exercise. (Later, Hauck would jokingly thank Bob Crippen for convincing them that they weren’t going to launch, thereby allowing them to enjoy the otherwise beautiful morning!) The winds did conspire to delay the launch by an hour and 38 minutes, and technicians also had to attend to failed vent fan fuses in the cooling systems of Covey’s and Lounge’s suits. At 11:28 a.m. EST, the Launch Director polled his team for their final status. As Hauck’s crew listened in, they expected Crippen to declare a “No Go,” on the basis of the high-level winds … but were surprised when he gave his consent for them to fly. The excitement began to build in the cockpit, and at 11:37 a.m. the marshy Florida landscape was rocked by the tremendous roar of three main engines and the golden flame of two boosters, carrying men into the heavens once again. For Dick Covey, watching the main engines brought back memories of Challenger in more ways than one … for he had been one of the Capcoms sitting in Mission Control, and he had spoken the last words to Commander Dick Scobee. On that terrible day, Covey had been too engrossed in his procedures to glance over at a monitor and see the carnage, but fellow astronaut Fred Gregory, seated to his right as the lead Capcom, saw it immediately and recognised it for what it was. As Gregory saw the video feed and Covey saw the data on his screen freeze, both men’s jaws hit the floor. At first, they wondered if a contingency abort was in progress. Had the range safety destruct system accidentally triggered? Had the SRBs been prematurely jettisoned? Had a main engine exploded? Should Covey radio further instructions to the crew and, if so, what could he possibly say? For the longest time, no one could be certain.

At length, it was Flight Director Jay Greene who spoke. “Lock the doors,” was his instruction, telling all controllers to secure their data for the investigation … and, instantly, Gregory and Covey and everyone else in the room knew that they were beyond contingencies or abort scenarios and the possibility of recovery was gone. Their friends were either dead or in the process of dying. Lock the doors. Three simple words. Three words which would also be spoken shortly after 9 a.m. EST on 1 February 2003. Three words which signified that all hope was lost.

Almost three years later, the wait for launch on STS-26 was exciting, but uncomfortable, and not just on account of the partial-pressure suits. “We were still using the urine collection devices,” said Covey, “and those aren’t particularly comfortable or easy to use. When you’re on your back for four hours out there … then it’s a long time. It’s uncomfortable.” The launch itself resembled previous launches, although all five men were keenly aware of what had happened to their predecessors and the level of anxiety peaked as they neared the 73-second psychological barrier beyond which Challenger had failed to pass. Before 51L, Rick Hauck felt that NASA had shuttle launches “wired,” but now he was relieved when the SRBs were jettisoned, as planned, two minutes into the ascent. When the fateful Go at throttle up call had come from Mission Control, perhaps not wanting to mimic Dick Scobee’s response, Hauck had replied simply, “Roger, Go.”

Covey remembered as the Mission Elapsed Time clock ticked past 88 seconds, “We’re all kind of thinking about what happened the last time the space shuttle had gotten to that point.” With six more minutes to go before Main Engine Cutoff, Hauck relayed the progress of the flight to Pinky Nelson on the middeck as Discovery passed through Mach 16 and onwards. At length, at 11:46 a.m., the sound of the engines was gone and the ghosts of Challenger, finally, were laid to rest. Several months earlier, it had been Dave Hilmers who suggested that the crew should commemorate their lost friends in some way. “We shared a personal loss in the class,” said Covey, “and personal loss of friends across those classes.” Hilmers had written it and gave a copy to Capcom Lacy Veach. On the third day of the flight, on Sunday, 2 October, each crew member took turns to deliver their piece of the eulogy to the Challenger astronauts. “It was something that needed to be done,” said Hauck. “It was a need that someone during the mission needed to say something that all of us could reflect on … and I gathered from what was said later by people in the office … that it captured the thoughts.”

Additionally, the crew felt the need to thank the ground teams who had invested so much sweat and tears in preparing them to fly. The Orbiter Processing Facility teams had labelled themselves “Loud & Proud” and, on occasion, they would wear “loud” Hawaiian shirts to work. When electrical power was provided to Discovery, the STS-26 crew were in attendance and were made honorary members of the “Loud & Proud” crowd and presented with honorary Hawaiian shirts, which they took into space with them. “Once we had the weighty issues behind us,” said Hauck, “we decided now is the time to break out the Hawaiian shirts.” They were passing over Hawaii at the time and downlinked some video of themselves, clowning around on the middeck in their shirts and sunglasses.

Life’s a Beach was Hauck’s comment. …

Aside from the enormous responsibility of getting America’s human space programme back on track, the deployment of TDRS-C occurred in a relatively straightforward fashion at 5:50 p.m. EST, some six hours and 13 minutes after launch. The IUS booster functioned perfectly, achieving geostationary orbit, and the satellite manoeuvred into its position above the Pacific Ocean at 171 degrees West longitude. Four days in space came to a spectacular conclusion at 9:37 a.m. PST (12:37 p.m. in Florida) on 3 October 1988, when Hauck and Covey brought Discovery smoothly onto Runway 17 at a sweltering Edwards Air Force Base. “A great ending to a new beginning,” was the congratulatory call from Capcom Blaine Hammond as the orbiter rolled to a stop. Vice President George Bush was in attendance, as were NASA Administrator James Fletcher, California Governor George Deukmeijian, and famed aviator General Chuck Yeager. Hauck fluttered an American flag as he descended the steps from the orbiter, a move which Time magazine derided as a “staged” example of a politician using the space programme for political gain.

“I remember writing a letter to the editor of Time,” said Hauck, “where this was opined and I stated the facts that … we were not prompted by anyone to bring a flag. That was our idea and we were very proud to have the vice president of the United States meet us at the bottom of the steps. It didn’t matter whether he was Republican, Democrat, or whatever.” That Monday afternoon, as Discovery returned safely home from a mission which Challenger and her crew had been cruelly denied, her otherwise “vanilla” mission demonstrated its profound significance, for had STS-26 failed the remarkable accomplishments which followed—launching and servicing Hubble and building the International Space Station, to name just a handful of triumphs—could not have been met. The achievement of the STS-26 crew and the thousands who made their mission possible allowed the ghosts of Challenger to be laid to rest and enabled the shuttle to rise from its knees and glimpse an exciting future.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s articles will focus on the 45th anniversary of Apollo 7, an October 1968 mission which saw America recover from the trauma of the Apollo 1 fire and test the spacecraft which would one day support the first human voyage to the Moon.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » ISS »

Thanks for the interesting articles, Mr. Evans.

Unknown to most, STS-26 came close to ending in a Columbia-style tragedy. John Young’s new book stated that Discovery suffered severe damage to her thermal protection system, coming “back from space in the worst condition of any orbiter flown in the shuttle program”…”one area on the orbiter wing had been so badly damaged during ascent that during reentry the tile eroded down nearly to the wing’s aluminum structure”.

What would have become of the Shuttle program if there had been back-to-back tragedies? I shudder to think!

Young’s book, “Forever Young”, is quite an interesting read. His background as an astronaut AND management gives his perspective a ton of credibility, not always seen in some astronaut bios.