As America and the world observes International Women’s Day this Sunday (8 March), the AmericaSpace team is reminded of the achievements of female space voyagers who have broken both the “glass ceiling” and the “atmospheric ceiling” over almost six decades. Ever since Valentina Tereshkova, an ordinary Russian factory worker, did something quite extraordinary by becoming the world’s first female space traveler in June 1963, women have gone on to chalk up records in spacewalking, satellite recovery and repair and long-term exposure to the hazardous microgravity environment.

And in 2024 or soon after, if current NASA plans endure and bear fruit, it can be confidently expected that the first female bootprint will appear on the surface of the Moon.

It is, however, a sad indicator of the political realities of the time that putting the first woman into space was done as little more than a stunt by Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. Although a group of U.S. women, colloquially dubbed the “Mercury 13”, had undergone similar training to the all-male Original Seven Project Mercury astronauts, the United States had no plans in the early 1960s to include females in its spaceflying corps. For Khrushchev, keen to demonstrate not only the Soviet Union’s technological might in terms of launching the first artificial satellite, the first probes to the Moon and the first man in space, the notion of sending a woman aloft would visibly show the supremacy of his brand of socialism.

And so in June 1963, Tereshkova flew for three days aboard the Vostok 6 spacecraft. She returned to Earth to be rightfully feted for her heroism, and indeed she logged more time in space on one mission than all of the Project Mercury flyers put together. Yet the political nature of her flight and the lack of appetite in the Soviet Union for further such voyages meant that it would be almost two decades before another Russian woman launched into space. Even today, only four female cosmonauts have flown, inclusing long-duration crew members Yelena Kondakova and Yelena Serova.

In the West, the end of the Apollo lunar program and the development of the Space Shuttle, together with a robust effort by NASA to make its future astronaut corps more representative of U.S. society, led to an emphasis on selecting minorities and women to fly on America’s newest space vehicle. And in January 1978, when 35 astronaut candidates were chosen for the shuttle program, they included in their ranks six women: medical doctors Anna Fisher and Rhea Seddon, physicist Sally Ride, electrical engineer Judy Resnik, geologist Kathy Sullivan and biochemist Shannon Lucid. Yet even this selection could not escape a political undercurrent, for initially only one of the women actually made the final cut, but the others were hired at the expense of several male shuttle pilot candidates, who were held over for a subsequent class.

Over the next few years, those six women flew not as political passengers in Tereshkova’s mold, but as fully fledged astronauts. In June 1983, Ride became the first U.S. woman in space, serving as flight engineer on STS-7 and participating in the deployment and retrieval of the Shuttle Pallet Satellite (SPAS) with orbiter Challenger’s mechanical arm. By this time, however, the Soviets had again gotten in on the action. In August 1982, civilian engineer Svetlana Savitskaya flew with two male cosmonauts to the Salyut 7 space station, to be welcomed by two other male cosmonauts.

Nor was this apparently demonstrative of a thaw in Russia’s stance towards women in space, for as soon as Savitskaya boarded the station one of her crewmates joked that perhaps she ought to start the cleaning. It was light-hearted banter, to be fair, and Savitskaya quickly slapped him down by declaring that housekeeping duties were the responsibility of the host and not the visitor, but the episode amply underlined the political nature of the mission. Two years later, in July 1984, Savitskaya became the first woman to log a second mission…and the first to perform a spacewalk. For over three hours, she and fellow cosmonaut Vladimir Dzhanibekov worked outside Salyut 7 on a variety of tasks, including an experimental welding tool. In early 1986, cynically timed to coincide with International Women’s Day, Savitskaya might have flown a third time, in command of an all-woman crew, but problems with Salyut 7 the previous summer precluded it.

Savitskaya might have missed out on becoming the first woman to command a space mission, but the United States seized this record when NASA chose its first female shuttle pilot, Eileen Collins, in January 1990. She went on to fly two shuttle missions as a pilot, before commanding STS-93 in July 1999 to deploy the Chandra X-Ray Observatory and later STS-114 in July 2005, the return to flight after the Columbia accident. Collins was later followed as a shuttle commander by Pam Melroy, who led STS-120 to deliver the Harmony module to the ISS in October 2007.

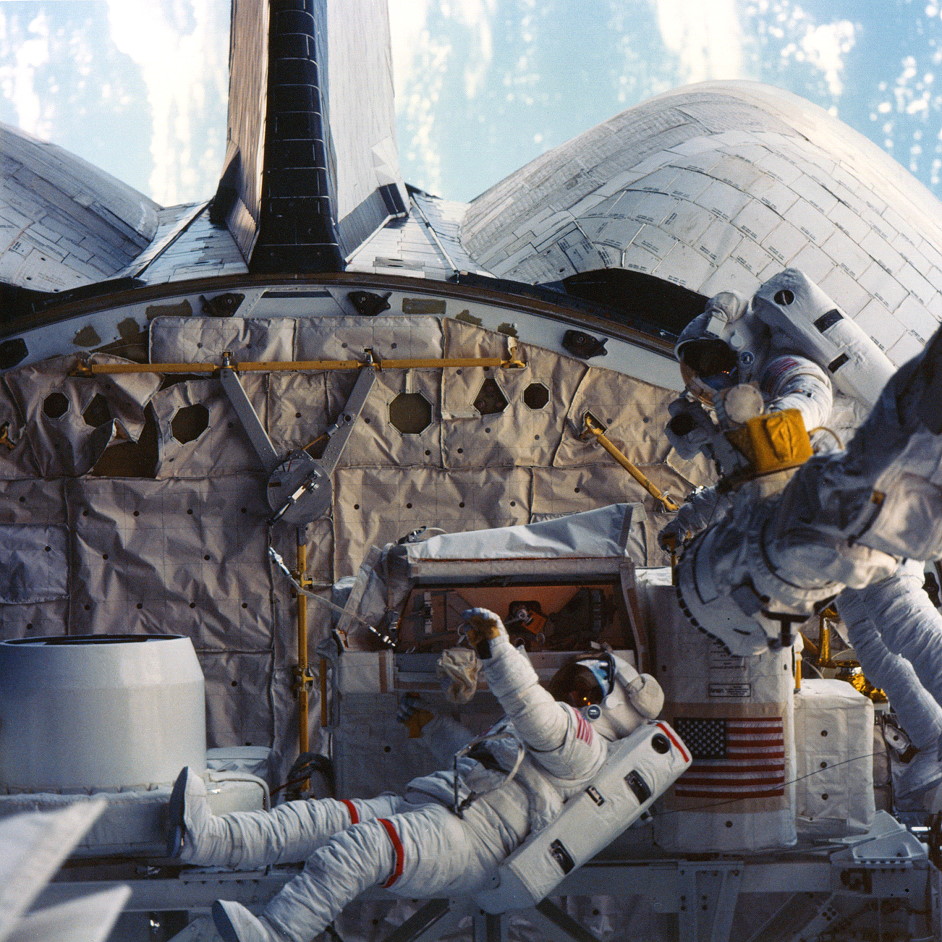

None of this—the flight of Savitskaya, the second mission, the spacewalk, the potential all-female crew—was done accidentally. Rather, in the fall of 1983 when Sally Ride was assigned to her second mission and Kathy Sullivan named to perform the first female Extravehicular Activity (EVA) on shuttle mission 41G, the Soviet political propaganda machine cranked and whirred back into action. And when Ride flew her second mission and Sullivan made her spacewalk in October 1984, both records had already been lost to the Soviets.

But in the final months before the loss of Challenger, more U.S. women roared into space. Judy Resnik endured the shuttle program’s first harrowing on-the-pad engine abort, Anna Fisher became the first mother in space and at 42 Shannon Lucid set a new record as the oldest woman in space. It was a record that Lucid would go on to break four more times in her subsequent career, including additional records for the longest single spaceflight by a woman, which she held for more than a decade. She also became the first woman to make a third, fourth and fifth space mission. To date, although five others followed in Lucid’s footsteps by logging fifth flights, no woman has yet launched into space on a sixth occasion.

But tragedy went hand-in-hand with triumph in these early years. Resnik and the first would-be civilian astronaut, schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe, were both killed in January 1986, when shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after liftoff.

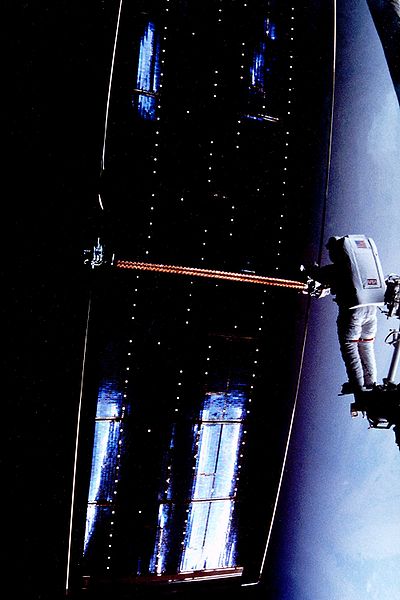

By the time the shuttle fleet returned to operational service in September 1988, NASA’s astronaut corps had swelled to include a sizeable minority of female members. Veteran Mary Cleave was first to fly in the wake of Challenger and over the next few years new records began to be set, with Bonnie Dunbar flying two of the longest shuttle missions in the early 1990s, Kathy Sullivan narrowly missing out on a second EVA to save the Hubble Space Telescope, Linda Godwin becoming the only woman to spacewalk outside Russia’s Mir space station and the International Space Station (ISS) and Kathy Thornton becoming the most seasoned female spacewalker with a total of three outings into vacuum. Thornton became the only woman to perform EVA during a Hubble servicing mission; and not just any Hubble servicing mission, either, but the failure-is-not-an-option first one.

Thornton’s empirical female record of three EVAs performed during shuttle missions STS-49 and STS-61 endured for more than a decade. And in March 2001, during STS-102, Susan Helms—the first long-duration female resident of the International Space Station (ISS)—participated in the longest-ever single EVA, lasting eight hours and 56 minutes. The record spacewalk, set jointly with Jim Voss, still stands today.

For more than ten years, between 2007 and 2017, the record for the greatest amount of cumulative EVA time by a woman alternated between long-duration ISS supremos Suni Williams and the first female Chief Astronaut Peggy Whitson. At present, Whitson holds the record with ten EVAs and over 60 spacewalking hours, as well as an adjunct record as the first female commander of a space station. Whitson also holds the record for the greatest amount of cumulative time spent in space by a woman, with over 665 days across her three long-duration ISS missions, and in 2017 completed a record-setting ISS increment almost ten months long. In doing so, she also became the oldest woman to travel into space, celebrating her 57th birthday aboard the space station in February 2017. Whitson’s single-flight record was broken last month when Christina Koch returned to Earth after 328 days. During her long stay, Koch and Expedition 61 crewmate Jessica Meir performed the first three all-female EVAs in history.

Women have set other records, too, with Britain’s Helen Sharman and South Korea’s Yi So-yeon presently the only two females to have also become their respective countries’ first-ever national astronauts. Sharman flew to Russia’s Mir space station in May 1991, whilst Yi did likewise to the ISS in April 2008. And returning home shoulder-to-shoulder with Yi was Russian cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko…and Peggy Whitson, marking the first occasion that women outnumbered men on a returning spacecraft.

As for launch, as many as three women flew aboard several shuttle missions, first among them STS-40 in June 1991. And Susan Kilrain and the late Janice Voss jointly hold the unusual record for the shortest interval between two spaceflights, having logged a mere 84 days between their return on STS-83 in April 1997 and their next launch together on STS-94 the following July.

As the world observes International Women’s Day, and mourns the recent passing of “Hidden Figure” Katherine Johnson, we are reminded of the immense contributions made by these female pioneers. In addition to U.S. and Russian astronauts, Canada’s Roberta Bondar and Julie Payette, Japan’s Chiaki Mukai and Naoko Yamazaki, France’s Claudie Haignere and Italy’s Samantha Cristoforetti have lived and worked in the microgravity environment during shuttle, Mir and ISS missions, whilst China’s homegrown space program saw Liu Yang and Wang Yaping travel to the Tiangong-1 orbital outpost. And with NASA’s Jessica Meir presently aboard the ISS and other women currently in active training, it can be expected that female involvement and leadership in future missions in low-Earth orbit and beyond are not a likelihood, but an inevitability.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.