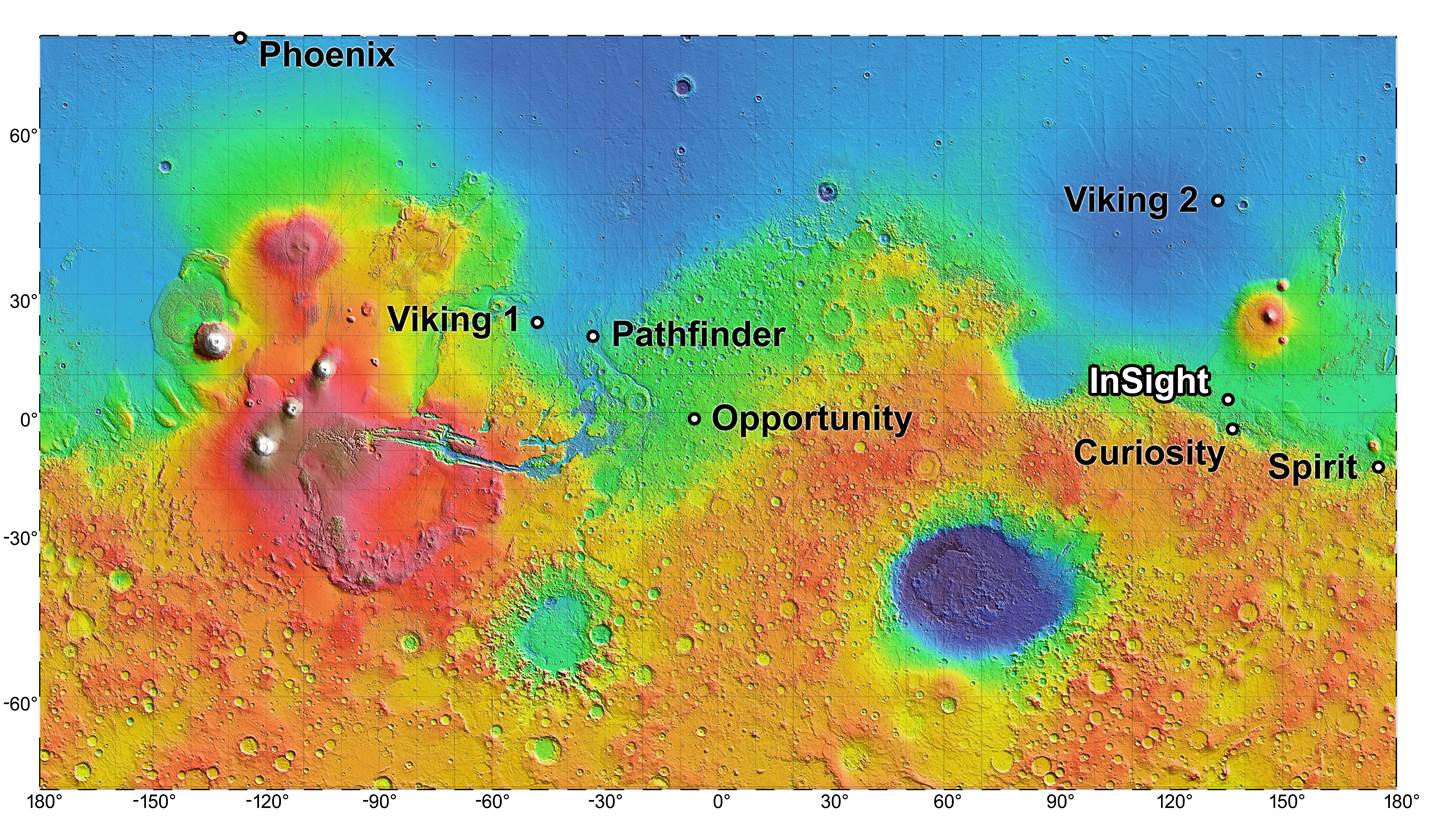

In late November, NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft is expected to thunder away from Earth on a one-way trip to study the thin atmosphere of Mars, but the next mission to land on the Red Planet’s surface will not launch until March 2016 at the earliest. In preparation for that mission, NASA announced today the selection of four potential landing sites out of 22 possible options, all of which are located on an equatorial plain in an area of Mars called Elysium Planitia.

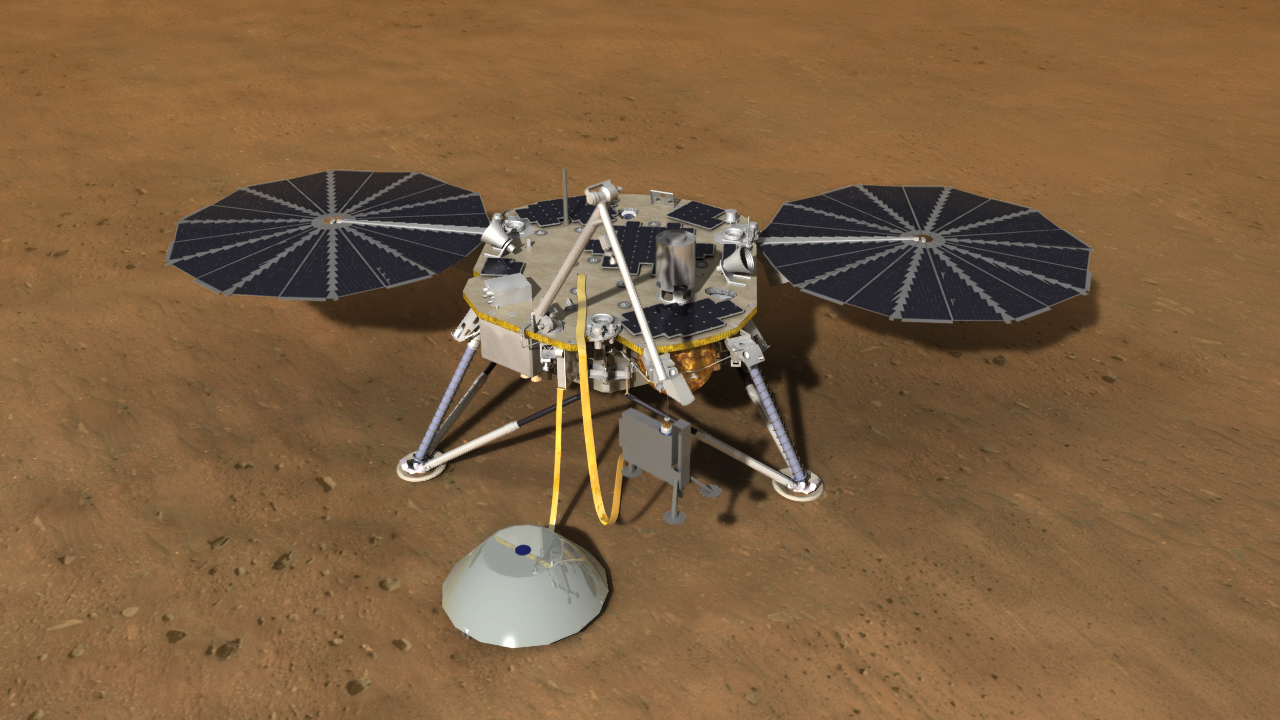

NASA’s Interior Exploration Using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy, and Heat Transport (InSight) lander will help unlock mysteries about the processes that shaped the rocky planets of the inner Solar System (including our own planet) more than four billion years ago. Previous landers have investigated the surface of Mars—its canyons, volcanoes, rocks, and soil—but InSight will be the first to seek out the fingerprints of the building blocks that led to the planet’s formation, which can only be found by looking far below the surface.

[youtube_video]http://youtu.be/RSTYvwodKO0[/youtube_video]

Video courtesy of NASA

“We picked four sites that look safest,” said Matt Golombek, a geologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who is leading the site-selection process for InSight. “They have mostly smooth terrain, few rocks, and very little slope.”

The four potential landing sites selected within Elysium Planitia all meet the basic requirements for InSight to carry out its mission. They each provide a large, flat area safe enough for an attempted landing, sufficient sunlight for power via the spacecraft’s solar arrays, and low elevation to allow for enough atmosphere to slow the spacecraft down as it plunges through the red martian sky at several times faster than a rifle bullet. Two cameras onboard NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter will spend the next few months investigating the potential landing sites, providing data that will be used to eventually select the best option long before InSight is launched.

“This mission’s science goals are not related to any specific location on Mars because we’re studying the planet as a whole, down to its core,” said InSight principal investigator at JPL Bruce Banerdt. “Mission safety and survival are what drive our criteria for a landing site.”

Each of the four potential landing sites also provide broken-up surface material or soil, characteristics which are critical to InSight’s success because the spacecraft will need to penetrate the ground to deploy a heat-flow probe. A landing site made up of solid bedrock or large rocks would not allow the probe to hammer itself the 3-5 yards into the ground it needs to reach in order to monitor heat coming from the planet’s interior.

Only two other areas on Mars are located near the equator with low elevation: Isidis Planitia and Valles Marineris. However, both locations are not suitable landing options because they are rocky and too windy. Valles Marineris does not provide any safe, flat landing place large enough to allow room for error either, should InSight miss its intended bull’s-eye within the landing ellipse.

All four potential landing sites measure 81 miles (130 kilometers) from east to west and 17 miles (27 kilometers) from north to south, and engineers calculate the spacecraft will have a 99-percent chance of landing within that ellipse if targeted for the center.

InSight will use three science instruments to carry out its mission to understand how the terrestrial planets of our Solar System formed, including the heat-flow probe. A seismometer, called SEIS, will take precise measurements of quakes and other internal activity on Mars, almost like taking its pulse. Another instrument, known as RISE, will track the way Mars wobbles when it is pulled by the Sun, measuring the Doppler shift and ranging of radio communications sent between the spacecraft and Earth, which in turn will help scientists determine the distribution of the planet’s internal structures and better understand how the planet is built.