For anyone wishing to place a safe bet, one could look no further than the exciting discoveries of planetary exploration. Every time a spacecraft is sent to a planetary destination for the first time, previously unimagined and fascinating discoveries are sure to follow and NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto could be no exception. Having successfully completed its historic flyby of the distant dwarf planet and its assortage of moons on July 14, the spacecraft has now began to slowly transmit its treasure trove of data back to Earth while currently on an outward trajectory from the Pluto system that will propel it farther into the Kuiper Belt. While the whole process of down linking New Horizons’ entire data collection will take the better part of the following 16 months, the preliminary science results to have come from the mission thus far have exceeded all expectations by revealing Pluto’s exotic landscapes in a spectacular manner, while also introducing new mysteries and unanswered questions about this fascinating icy world in the outer reaches of the Solar System.

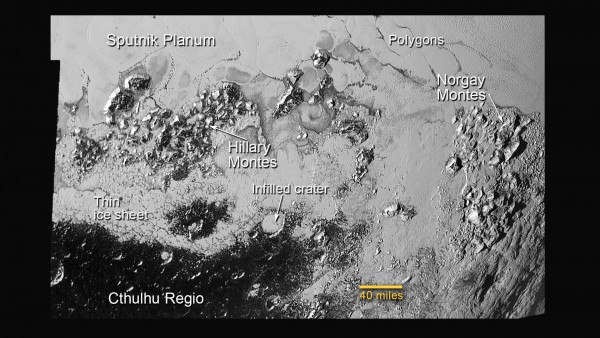

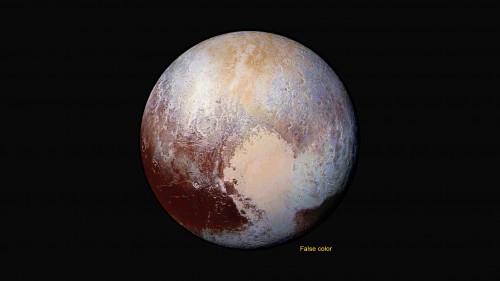

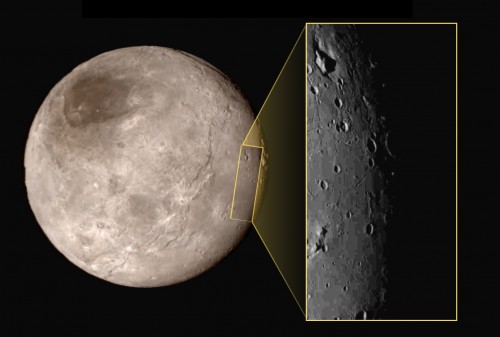

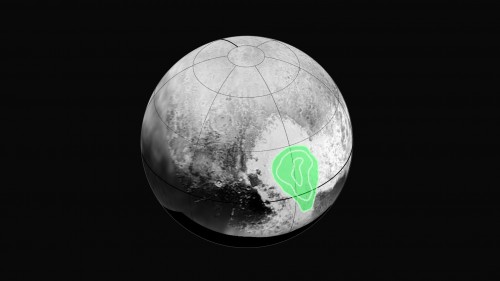

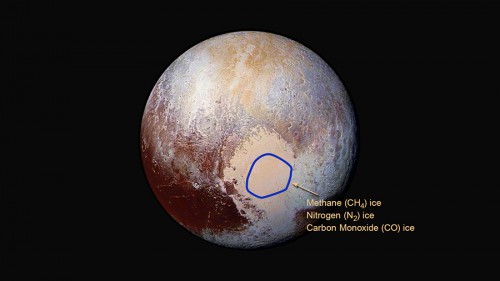

The first post-flyby images to have come from the New Horizons mission one day after closest approach proved to be of great surprise to scientists and space enthusiasts alike, revealing the multi-faceted terrains of both Pluto and Charon, including the discoveries of mountains of water ice on Pluto and a vast dark-colored polar region on Charon amidst a dramatically varied landscape. One of the surface features that have stood out in these detailed images is a vast, 1,590-km-wide, heart-shaped region on Pluto, which has been informally named Tombaugh Regio, in honor of the late astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, who discovered Pluto in 1930. The entire region consists of a surprisingly flat and bright terrain that is almost crater-free. This absence of impact cratering suggests that Tombaugh Regio is geologically very young, in the order of being approximately not more than 100 million years long, with further data suggesting that it may be geologically active even today. A second round of more detailed, close-up images, and other data that were beamed back from New Horizons last week, provided scientists with important new insights regarding the southern borders of Tombaugh Regio, by revealing an array of enigmatic polygonal features in an area named Sputnik Planum, which were surrounded by a series of mountains made of water ice, informally called Norgay Montes, that reach as high as 3,500 meters from the ground.

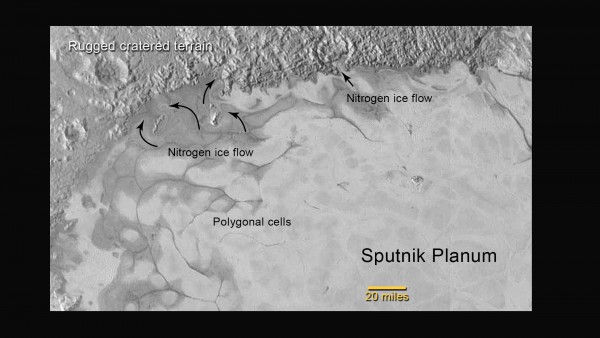

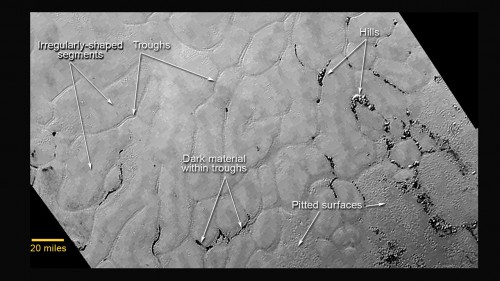

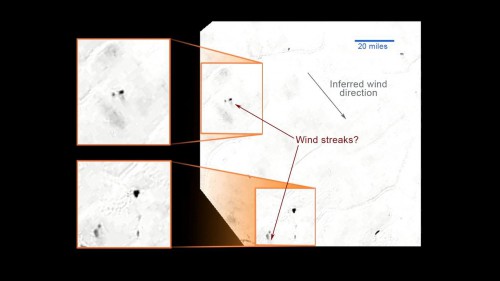

In subsequent higher resolution images released by the mission’s science team earlier this week, new exciting details about Sputnik Planum emerged, including the presence of a second mountain range called Hillary Montes, albeit smaller than Norgay Montes, with an approximate height between 1 and 1.5 kilometers. What has really stood out for the mission’s science team in these images is the fact that Sputnik Planum’s southern terrain is a very complex one, with both mountain ranges being surrounded by geologically recent flows of probably nitrogen ice that have resurfaced much of the neighboring landscape. This type of recent geological activity in fact stood out much more spectacularly in the northern border of Sputnik Planum, where New Horizons’s images clearly revealed the presence of exotic glacier activity in the form of nitrogen ice flows that stand in stark contrast to a rugged cratered terrain farther north, which is believed to be billions of years old. Such geologic activity can only mean that the flattened terrain of Sputnik Planum must not be older than a few tenths of millions of years, indicating that Pluto has been a surprisingly active world in recent geologic times and could be so even today. “Glaciers on the Earth are made of [water] ice, like in Antarctica and Greenland, but water ice at Pluto’s temperatures won’t move anywhere, it’s immobile and brittle,” said Bill McKinnon, co-investigator for the New Horizons mission, at at the Washington University in St. Louis, during the presentation of New Horizons’ latest findings at a media briefing that was held earlier today at NASA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. “But on Pluto, the kinds of ices we think make up the planet, like nitrogen, carbon monoxide and methane ice, are geologically soft and malleable and they will flow in the same way that glaciers do on the Earth. So, we have actual evidence for basically recent geological activity.” “We’ve only seen surfaces like this on active worlds like Earth and Mars,” adds John Spencer, member of the New Horizons science team at the Southwest Research Institute, in Boulder, Colo. “I’m really smiling.”

These latest findings have also helped to settle one big question regarding whether Pluto could indeed be a geologically active body so far from the Sun, in the frozen expanses of the Kuiper Belt. “Can icy worlds minding their own business and not orbiting some giant planet, also be geologically active? And the answer is, ‘obviously yes’, says Jeff Moore, co-investigator for New Horizons, at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. “Pluto is every bit as geologically active as any other place we’ve seen in the Solar System and this really answers one fundamental question about whether ice worlds are able to do their own thing in their own right, or are they dependent upon the help of the big planets they orbit around”.

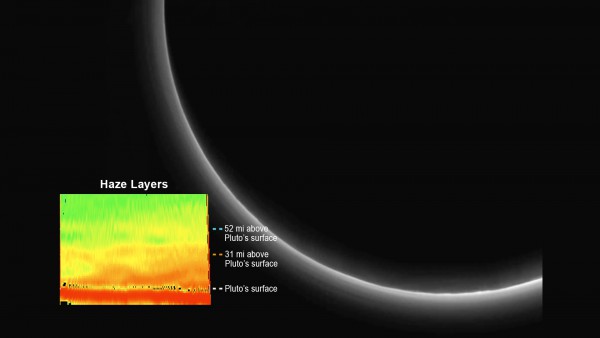

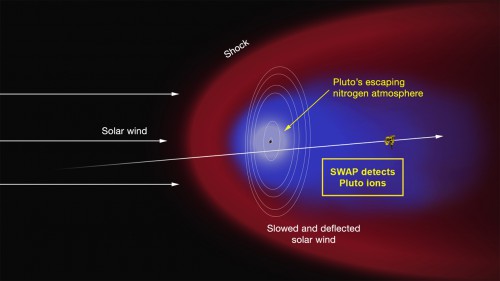

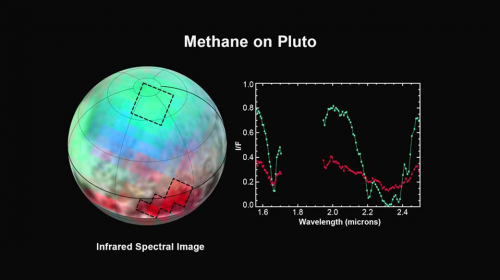

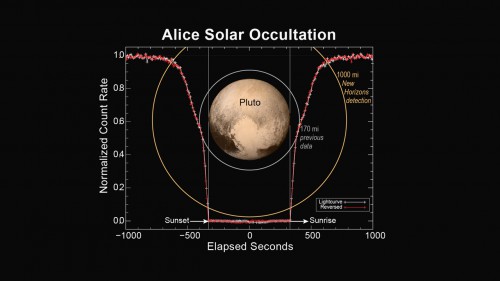

While Pluto’s surface was revealed to be a really exciting one, the planet’s atmosphere proved to be equally fascinating. As part of New Horizons’ mission, scientists on the ground directed one of the Deep Space Network’s large antennas to transmit a radio signal towards the spacecraft as the latter was passing behind Pluto, following its closest approach to the planet on July 14. The purpose of this experiment was to have the DSN’s signal pass through Pluto’s atmosphere before being received by New Horizons, thus allowing scientists to probe the planet’s atmospheric dynamics in great detail. The end result has paid off handsomely, providing scientists with their first ever views of the atmospheric structure and weather of a Kuiper Belt object. From these results, it was revealed that Pluto’s atmosphere has a unexpetidly complex and fascinating structure, with the mission’s science teams detecting no less than two distinct haze layers at different altitudes, located approximately 50 and 80 km above the ground respectively, which extend as high as 130 km, contrary to theoretical predictions which posited that such structure could not be found that high into Pluto’s atmosphere. It is thought that these haze layers are the result of photolytic reactions that take place in the Plutonian atmosphere. The process begins at high altitudes where methane molecules are abundant. There, the latter are broken up by sunlight into simpler compounds which in turn drive a set of chemical reactions that result in the production of more complex organic compounds like ethylene and acetylene, which were also detected in Pluto’s atmosphere by New Horizons. These organic compounds then start to build up and begin to condense at lower altitudes where temperatures are lower, eventually forming the haze layers that were observed by New Horizons. Nevertheless, these observations are still in the preliminary stages, with more data expected to be downlinked in the following months which would allow scientists to have a more complete picture of the exact goings-ons in the Plutonian atmosphere. Meanwhile, the data that have already been received, are already forcing scientists to think in new ways regarding the dynamics of Pluto’s fascinating atmosphere. “We’re going to need some new ideas to figure out what’s going on,” says Michael Summers, co-investigator for the New Horizons mission, at the George Mason University in Virginia.

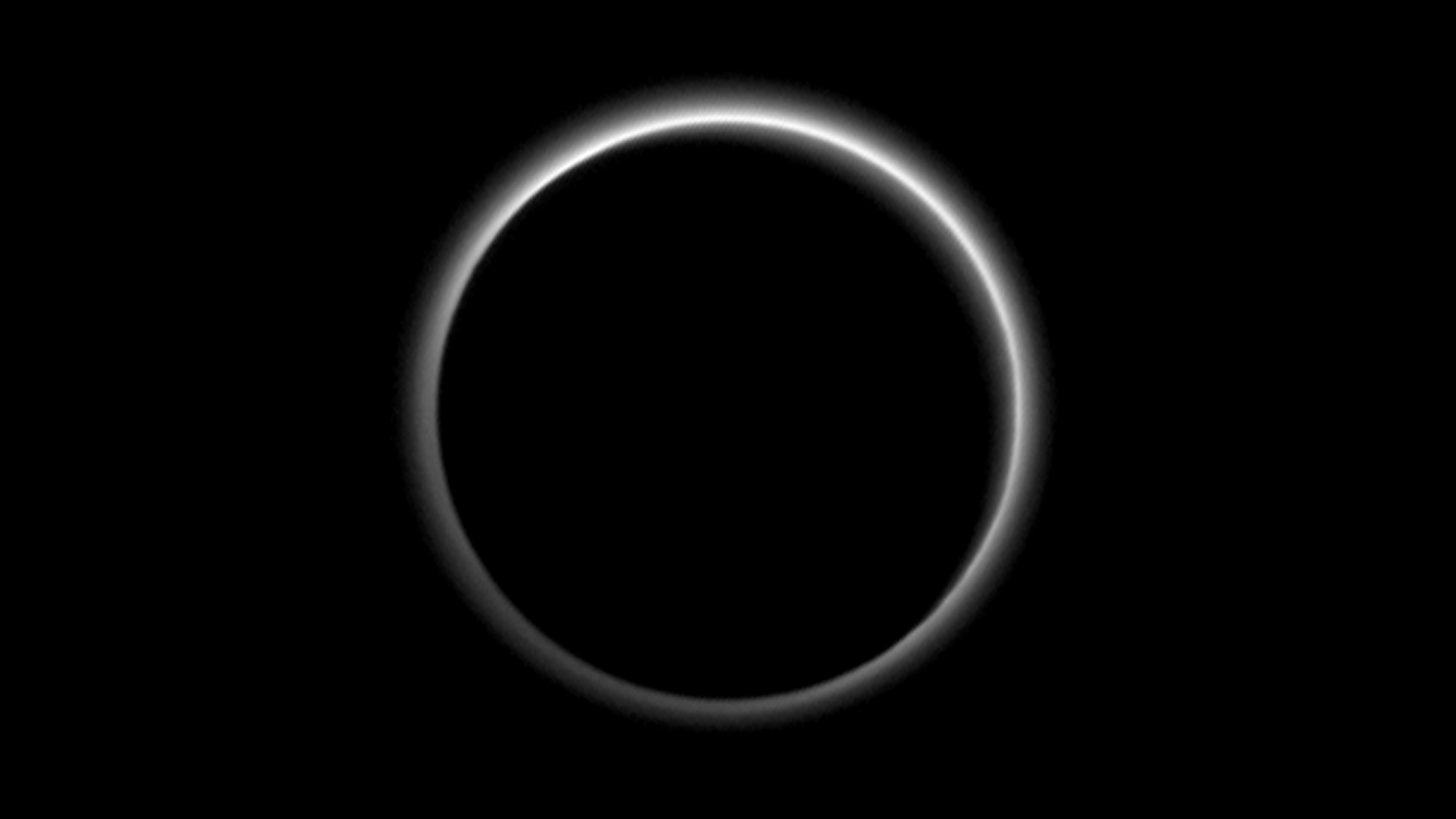

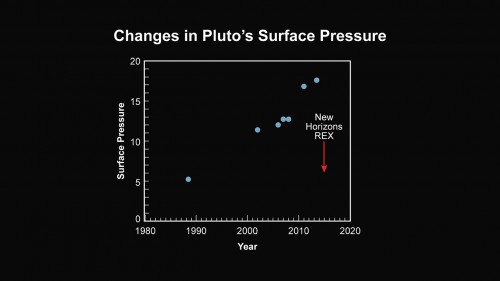

These atmospheric observations were also enhanced by a dramatic and awe-inspiring image of Pluto that was taken by New Horizons immediately after closest approach on July 14, as the spacecraft passed behind the planet on its outward trajectory away from the Pluto system. This spectacular image of Pluto backlit by the distant Sun, not only provided scientists with important data on the planet’s atmospheric structure but it also brought home the reality, breathtaking beauty and awe of space exploration. “This is our equivalent on New Horizons of the Apollo ‘Earthrise’ photograph that proved we were there,” says Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute. “You can only get this image by going to Pluto, crossing to the far side and looking back.” Another key finding to come out from these latest data sets, is the measurement of Pluto’s atmospheric pressure near the planet’s surface, which was found to be much lower than expected. Previous observations by the Hubble Space Telescope during the last decade had shown that even though Pluto was past the perihelion point in its orbit, its atmosphere was still expanding and becoming more massive. In-situ measurement that were taken with New Horizons’ onboard Radio Science Experiment, or REX, during the spacecraft’s close fly by, have instead shown that Pluto’s atmospheric pressure near the surface was 10 micorbars at most, which meant that its mass has decreased by a factor of two since the earlier Hubble observations. Even though these measurements by REX are preliminary, with more detailed ones awaiting to be downlinked in the following months, they nevertheless show evidence that Pluto’s atmosphere may have started to freeze up as the planet moves further away from the Sun in its 248-year-long orbit. “For the first time we have ground truth, measuring the surface pressure at Pluto, giving us an invaluable perspective on conditions at the surface of the planet,” says Ivan Linscott, member of New Horizons’ science team, at Stanford University. “This crucial measurement may be telling us that Pluto is undergoing long-anticipated global change.”

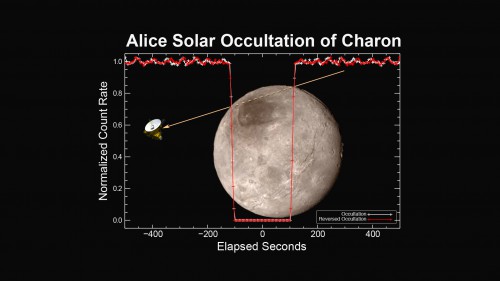

Probably not as surprisingly, contrary to New Horizons’ quite unexpected findings regarding Pluto’s atmosphere, the spacecraft found no traces whatsoever of an atmosphere around Charon, Pluto’s largest moon. During New Horizons’ close passage of the Pluto system the spacecraft passed behind Charon as the latter occulted the Sun, in a trajectory that was best suited for the detection of any possible atmosphere. Nevertheless, New Horizons found that the Sun’s light was blocked abruptly by Charon during the occultation, while detecting no signs of atmospheric refraction or any subtle declines in sunlight that would indicate the presence of a perceptible atmosphere of any kind.

With the New Horizons spacecraft now more than 10 days past its closest approach of Pluto and its moons, scientists are well into their study and analysis of the spectacular images and data that have been returned from the mission so far. With a little less than 5 percent of New Horizons’ entire data set having been returned to Earth, it’s safe to say that even more exciting and unexpected discoveries await us further down the road. “We knew that a mission to Pluto would bring some surprises, and now, 10 days after closest approach, we can say that our expectation has been more than surpassed,” says John Grunsfeld, NASA’s associate administrator for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate, in Washington, D.C. “With flowing ices, exotic surface chemistry, mountain ranges, and vast haze, Pluto is showing a diversity of planetary geology that is truly thrilling.”

If these early results are any indication, the next 16 months of constant Pluto science data down linking will be quite a ride.

A simulated flyover of northwestern Sputnik Planum and Hillary Montes on Pluto, assembled from images taken with New Horizons. Features as small as 1 kilometer across are visible. Video Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Below are more images and data from the New Horizons mission:

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » New Horizons »

It is now quite evident that the New Horizons mission has underscored the rich diversity right here in our own solar system. We have ample opportunities to seek evidence of microbial life in relatively close proximity to Earth and to ignore this would do a huge disservice to mankind. The new photos are indeed “jaw dropping.”

In the nearly 60 years of the Space Age, we can now say that all nine planets (yes, Pluto is the ninth planet) have been officially explored. What an abundance of comparative information on our “family!” I and others clamor for the full-scale assault of more landers, orbiters and other missions to the planets and moons. We have repeatedly demonstrated the technologies to make this happen. I am also awe of the scientific discoveries New Horizons has made so far in this most interesting article.