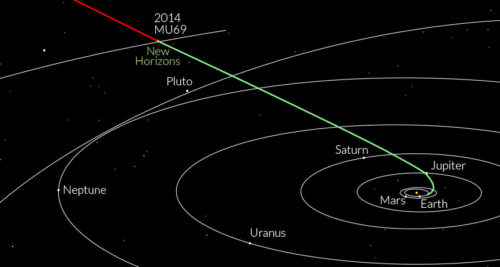

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft has just completed its newest flyby – of the Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) called Ultima Thule (aka 2014 MU69). New Horizons sped past the small but intriguing little world at 12:33 a.m. EST on Jan. 1, 2019. The event marks a milestone for the most distant object in the Solar System ever to be visited by a spacecraft from Earth. The good news was first reported during a NASA press conference on January 1. The flyby has revealed an “entirely new kind of world” according to today’s follow-up press conference.

“This flyby is a historic achievement,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “Never before has any spacecraft team tracked down such a small body at such high speed so far away in the abyss of space. New Horizons has set a new bar for state-of-the-art spacecraft navigation.”

“Congratulations to NASA’s New Horizons team, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and the Southwest Research Institute for making history yet again. In addition to being the first to explore Pluto, today New Horizons flew by the most distant object ever visited by a spacecraft and became the first to directly explore an object that holds remnants from the birth of our solar system,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. “This is what leadership in space exploration is all about.”

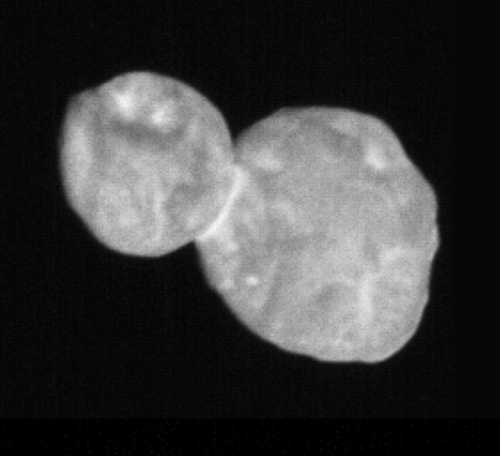

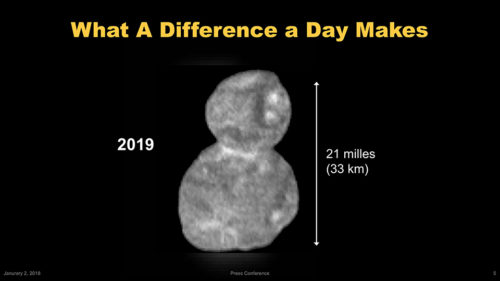

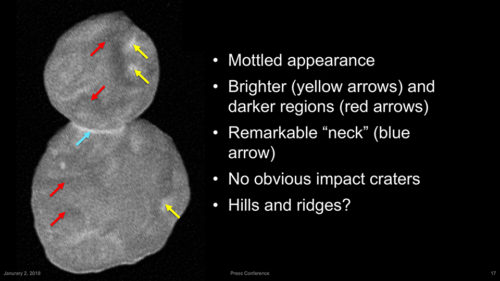

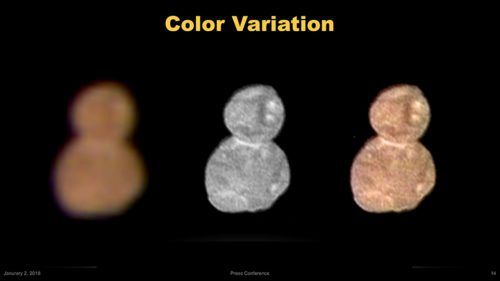

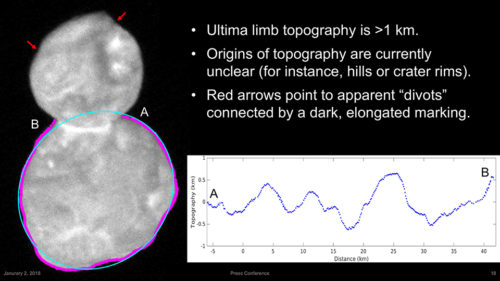

The new images – taken from as close as 17,000 miles (27,000 kilometers) during approach – revealed Ultima Thule to be a “contact binary,” consisting of two connected spheres. End to end, the little world measures 19 miles (31 kilometers) in length. The team has dubbed the larger sphere “Ultima” (12 miles/19 kilometers across) and the smaller sphere “Thule” (9 miles/14 kilometers across).

One of the most prominent features is a distinct brighter “band” circling the “neck” where the two spheres connect. Scientists don’t know how it formed yet, but it may be composed of smaller grains of material that accumulated in the neck crevice. Scientists said the two lobes probably came into contact with each other very, very slowly, no faster than two cars in a fender-bender.

This is the first time ever that humanity has explored an object in the Kuiper Belt, the region of asteroid-like bodies in the outer Solar System, out past the orbit of Neptune.

Signals from the spacecraft reached the mission operations center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) yesterday at 10:29 a.m. EST, almost exactly 10 hours after New Horizons’ closest approach to the object.

“New Horizons performed as planned today, conducting the farthest exploration of any world in history – 4 billion miles from the Sun,” said Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “The data we have look fantastic and we’re already learning about Ultima from up close. From here out the data will just get better and better!”

Images and other science data are currently being sent back to Earth. The first images showed Ultima Thule in low resolution, as expected, but they were good enough to see that the object was shaped kind of like a bowling pin or peanut, with two distinct lobes, and is approximately 20 by 10 miles (32 by 16 kilometers) in size.

“New Horizons is like a time machine, taking us back to the birth of the solar system. We are seeing a physical representation of the beginning of planetary formation, frozen in time,” said Jeff Moore, New Horizons Geology and Geophysics team lead. “Studying Ultima Thule is helping us understand how planets form – both those in our own solar system and those orbiting other stars in our galaxy.”

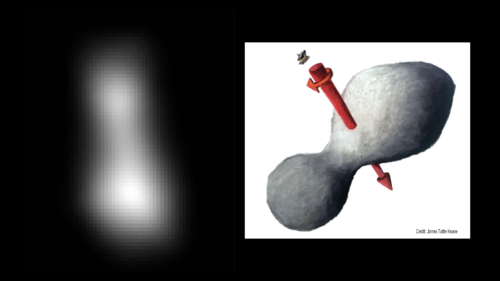

A previous mystery reported on earlier – the puzzling lack of a light curve – has also been solved. Ultima Thule is “spinning” like a propeller, with its axis tinted in the direction of the spacecraft. This explains why its brightness didn’t seem to change as it rotated.

“New Horizons holds a dear place in our hearts as an intrepid and persistent little explorer, as well as a great photographer,” said Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory Director Ralph Semmel. “This flyby marks a first for all of us — APL, NASA, the nation and the world — and it is a great credit to the bold team of scientists and engineers who brought us to this point.”

The flyby itself may be over now – almost 13 years after its launch – but New Horizons will continue to send back images and science data in the days and months ahead. It will take about 20 months for all of the data to be sent to Earth. Scientists will also look for a possible next target, another KBO, for a flyby sometime in the 2020s.

“Reaching Ultima Thule from 4 billion miles away is an incredible achievement. This is exploration at its finest,” said Adam L. Hamilton, president and CEO of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “Kudos to the science team and mission partners for starting the textbooks on Pluto and the Kuiper Belt. We’re looking forward to seeing the next chapter.”

“In the coming months, New Horizons will transmit dozens of data sets to Earth, and we’ll write new chapters in the story of Ultima Thule – and the Solar System,” said Helene Winters, New Horizons Project Manager.

All of the press conference slides can be seen here and here and all raw images from the flyby are available here.

More information about New Horizons is available on the mission website.

There simply not enough superlatives to describe this outstanding achievement. To think that a spacecraft can (1) last 13 years of flight and (2) hit multiple targets with such accuracy is, as I always say, a testament to the genius of the scientists and engineers. Bravo@