So-called “waterworlds” have been found to be surprisingly common in the Solar System—small icy moons which have ice crusts but oceans of liquid water below the surface. These include Jupiter’s moons Europa and Ganymede and Saturn’s moons Enceladus and Titan, and possibly others. These moons are cold and very far from the Sun, but heated inside by the gravitational pull of their giant host planets and/or radioactivity. Now there’s another Solar System body which, even more surprisingly, some scientists think has a subsurface ocean: Pluto.

There had been suggestions before that Pluto used to have an internal ocean a long time ago, although it was thought to have most likely frozen solid by now. But a new study adds to the evidence that not only was there an ocean, but that it is quite possibly still liquid, or at least partially liquid, today.

The new study uses data obtained by the New Horizons spacecraft after it flew past Pluto in July 2015. The study, led by Noah Hammond, a graduate student in Brown’s Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, combines a thermal evolution model of Pluto with the updated information from New Horizons. Amy Barr of the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona and Brown University geologist Marc Parmentier are co-authors. It will be published in Geophysical Research Letters.

“Thanks to the incredible data returned by New Horizons, we were able to observe tectonic features on Pluto’s surface, update our thermal evolution model with new data and infer that Pluto most likely has a subsurface ocean today,” said Hammond.

Basically, the research shows that if Pluto’s ocean had frozen completely, the entire dwarf planet would have shrunk. Instead, New Horizons found evidence that Pluto’s surface has expanded.

“What New Horizons showed was that there are extensional tectonic features, which indicate that Pluto underwent a period of global expansion,” Hammond said. “A subsurface ocean that was slowly freezing over would cause this kind of expansion.”

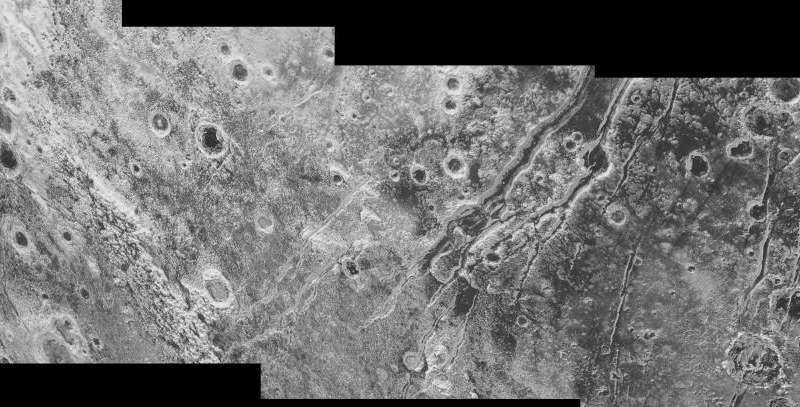

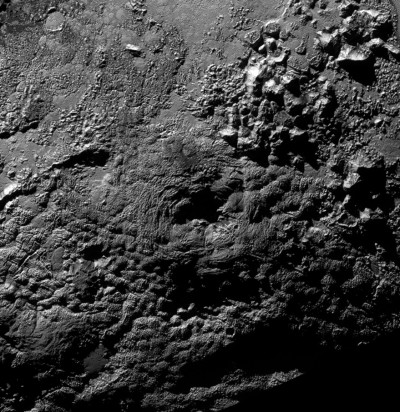

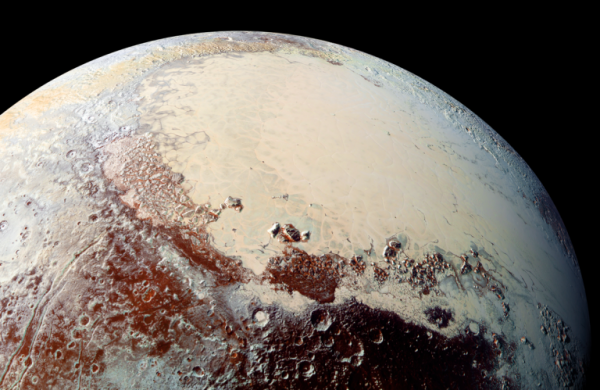

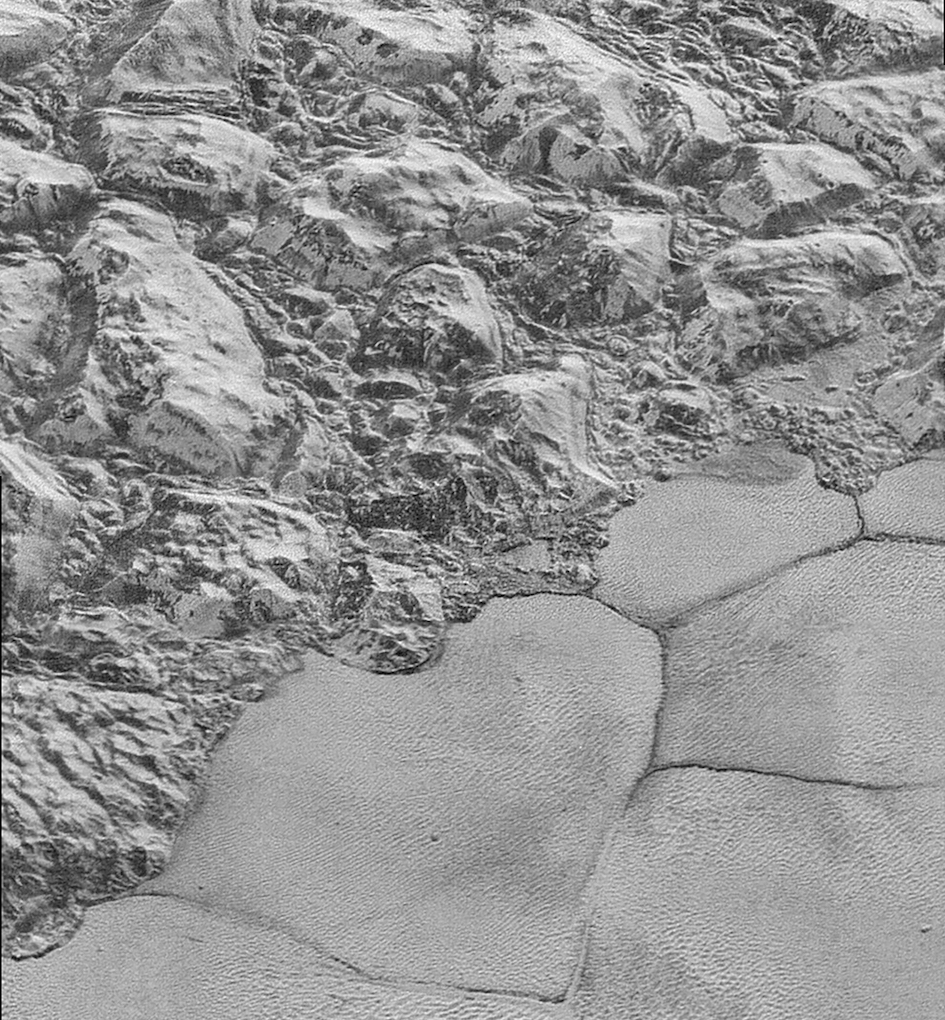

Indeed, Pluto was found to be more geologically active than expected, with the huge tectonic features, such as faults hundreds of kilometers long and as deep as 2.4 miles (4 kilometers). There are also tall mountains of solid water ice, as hard as rock, as well as vast smooth plains and glaciers of nitrogen and methane ices. “Icebergs” of water ice can be seen “floating” on those plains, as well as many small pits, evidence of convection where the nitrogen ice slowly makes its way up to the surface from deeper below and refreshes the surface over and over again; the effect has been compared to that of a lava lamp. New Horizons also found possible cryovolcanoes on Pluto, where ice would erupt to the surface instead of lava. There is also now evidence that Pluto once had rivers and lakes of liquid nitrogen on its surface. Far from simply being a frozen and inactive world, Pluto is dynamic in its own unique ways, different from any other place in the Solar System.

But at the bitterly cold temperatures found on Pluto, how could there still be an ocean underground? Researchers think that the interior of Pluto contained enough radioactive elements to melt part of the outer ice shell, creating the layer of liquid water below the surface. Over time, however, that ocean would slowly begin to freeze. The question now is: Has it frozen completely or is some of it still liquid? If Hammond is correct, there is still at least a part of that ocean that is still liquid.

According to the thermal evolution model for Pluto, combined with the new findings from New Horizons, if the ocean had completely frozen by now, the ice would have been covered from “normal” ice to a type called ice II, due to the extremely low temperatures and high pressure within the dwarf planet. That kind of ice would take up less space, causing a global contraction instead of expansion. But that’s not what New Horizons found.

“We don’t see the things on the surface we’d expect if there had been a global contraction,” Hammond said. “So we conclude that ice II has not formed, and therefore that the ocean hasn’t completely frozen.”

The case for the possible ocean isn’t a slam dunk yet; it depends on the thickness of the ice shell. Ice II would only form if the ice shell was more than 161 miles (260 kilometers) thick. Otherwise, the entire ocean could have frozen without forming ice II or causing contraction. However, the newest models for Pluto’s interior based on New Horizons data indicate the ice shell is likely closer to 186 miles (300 kilometers) thick. This is also supported by the presence of the nitrogen and methane ices.

“Those exotic ices are actually good insulators,” Hammond said. “They may be helping Pluto from losing more of its heat to space.”

“That’s amazing to me,” he added. “The possibility that you could have vast liquid water ocean habitats so far from the Sun on Pluto – and that the same could also be possible on other Kuiper belt objects as well – is absolutely incredible.”

It is a fascinating possibility, bolstered by the new evidence and research. Of course, wherever there is an ocean, the question of life inevitably comes up. For Pluto, it is anyone’s guess at this point. If there were chemical nutrients available and a source of geothermal heat on the ocean bottom, that would increase the chances. Life thrives in deep ocean environments such as those on Earth. But nothing is known yet about the conditions within Pluto’s ocean, assuming it exists. Both Europa’s and Enceladus’ oceans are now thought to be potentially habitable since evidence has been found for the needed chemical nutrients and heat, including evidence from Cassini for hydrothermal vents on the bottom of Enceladus’ ocean, similar to those found on Earth. But Pluto’s ocean is much deeper down from the surface (and much farther away) than those ones, so it will be some time before much else is known about possible habitable conditions. If nothing else, however, it would show that such alien oceans are common, at least in our own Solar System—an exciting discovery in itself.

New Horizons is now heading toward its next target in the Kuiper Belt, a much smaller object called 2014 MU69, which the spacecraft will pass at a distance of only about 1,900 miles (3,000 kilometers), four times closer than the Pluto flyby. 2014 MU69 is only about 13 to 25 miles (21 to 40 kilometers) across, which is similar in size to Mars’ two tiny moons, Phobos and Deimos. 2014 MU69 was discovered in 2014 by the Hubble Space Telescope, as part of a search for other Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs).

A new mission extension proposal has also been submitted to NASA, called “KEM,” or Kuiper Belt Extended Mission, where New Horizons’ mission would continue until at least 2021. If approved, as expected, New Horizons could make more distant observations of about 20 other KBOs as well and even search for rings around some of them.

According to John Grunsfeld, chief of the NASA Science Mission Directorate in Washington: “Even as the New Horizon’s spacecraft speeds away from Pluto out into the Kuiper Belt, and the data from the exciting encounter with this new world is being streamed back to Earth, we are looking outward to the next destination for this intrepid explorer. While discussions whether to approve this extended mission will take place in the larger context of the planetary science portfolio, we expect it to be much less expensive than the prime mission while still providing new and exciting science.”

Data from the Pluto flyby is still being sent back and analyzed, and it seems that this exciting mission will continue for several more years to come.

Follow our New Horizons mission page for regular updates.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » New Horizons »

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:New Horizons Finishes Returning Pluto Data to Earth Before Continuing Farther into Kuiper Belt « AmericaSpace