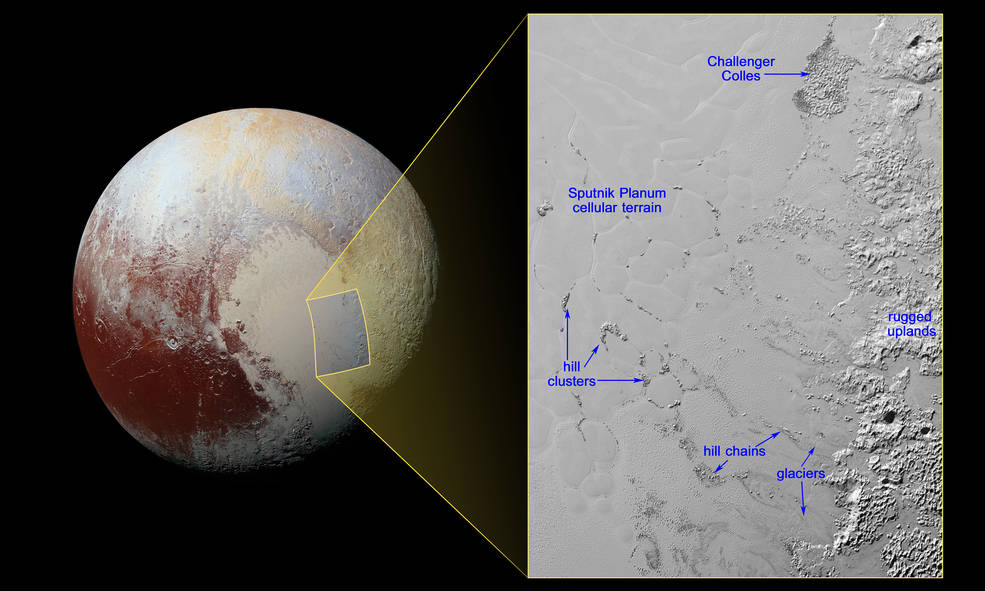

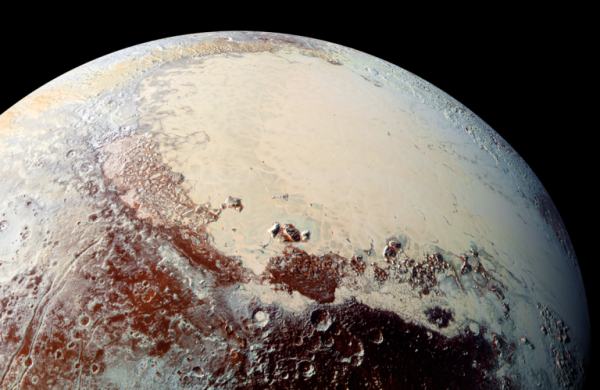

Pluto is a tiny world and incredibly distant from the Sun, so it was a pleasant surprise for scientists last summer when the New Horizons spacecraft found that it is such a geologically active and dynamic place, with vast “seas” of nitrogen ice and glaciers, tall mountains of rock-hard water ice, and possible ice volcanoes. A new update this week focuses on some of the most interesting features discovered: iceberg-like blocks of water ice which “float” in the “seas” of softer nitrogen ice.

These icebergs are another good example of processes which mimic ones on Earth, but are uniquely alien. On our planet, huge chunks of water ice float in cold seas and oceans of water, but on Pluto it’s a bit different. The icebergs are still composed of water ice, but they are embedded in the softer nitrogen ice of smooth icy plains or “seas” like Sputnik Planum. At Pluto’s exceedingly cold temperatures, water ice is as solid as rock, while nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide ices are less rigid and can slowly “flow” much like glaciers on Earth.

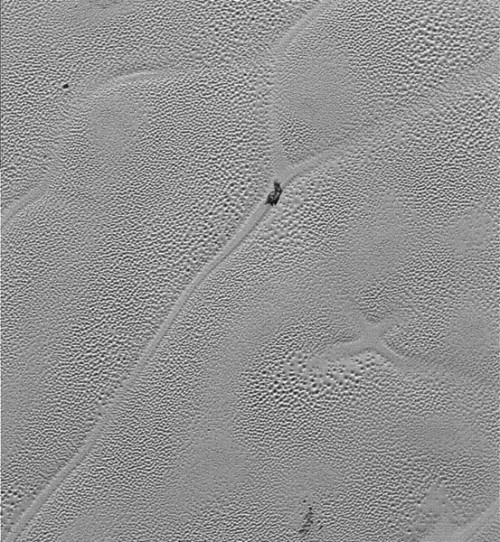

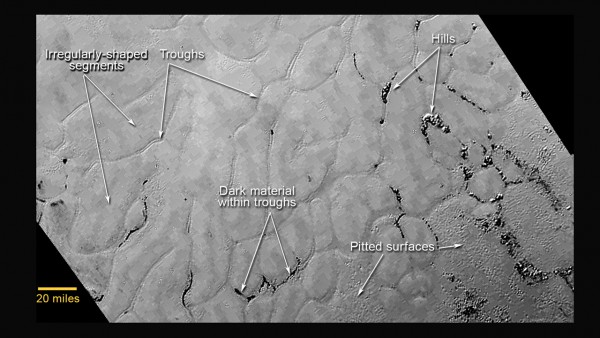

These icebergs, or isolated hills, are thought to be fragments of the same water ice mountains which border the nitrogen seas. These fragments broke away from the “coastal areas” and now very slowly drift amid the frozen nitrogen; they are buoyant since water ice is less dense than nitrogen ice. The glaciers along the shoreline empty into the larger expanse of ice, carrying the fragments with them. “Chains” of icebergs then form along the flow paths of the glaciers, and when they reach the central portions of the sea, they are pushed toward the edges of the large “cells” which dominate this region. Those cells are thought to be areas where soft nitrogen ice from below comes up to the surface in a convection process.

One region in particular, called Challenger Colles, seems to have a large number of icebergs; it was named in honor of the lost crew of the Challenger Space Shuttle. In this area, the icebergs appear to have been “beached” since they are close to the shoreline boundary with the mountains and away from the cellular terrain. The nitrogen ice sea would be shallower in this region than farther out, just like bodies of water on Earth.

Apart from the icebergs, it was also recently reported that Pluto has much more water ice on its surface than previously thought. While water ice is abundant, large areas such as the smooth icy plains of Sputnik Planum are dominated by nitrogen ice, as well as methane and carbon monoxide ices elsewhere. Just why the mountains and icebergs are composed of water ice instead still isn’t fully understood, although it is known that Pluto’s crust is also water ice.

“Large expanses of Pluto don’t show exposed water ice,” said science team member Jason Cook, of SwRI, “because it’s apparently masked by other, more volatile ices across most of the planet. Understanding why water appears exactly where it does, and not in other places, is a challenge that we are digging into.”

According to Alan Stern, New Horizons Principal Investigator: “We did not predict that a small planet like Pluto could still be active and would not have completely cooled off. The Pluto system surprised us in many ways, most notably teaching us that small planets can remain active billions of years after their formation. We were also taught important lessons by the degree of geological complexity that both Pluto and its large moon Charon display.”

Sputnik Planum itself is a giant shallow basin, now filled with the nitrogen ice, which is thought to have been formed by an impact from a large asteroid about 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) across. Scientists think the impact which created both the basin and the adjacent mountains may have occurred elsewhere on Pluto, then later migrated close to the equator where it is now.

“[Sputnik Planum] is so large and its volume so great that the negative mass anomaly caused by its impact has very likely caused this object to move to its current position near the equator,” Stern said.

The relatively soft surface of Sputnik Planum is also covered with many small pockmark-like pits, which are likely related to the convection process of nitrogen ice rising up to the surface from below. The surface is completely free of other impact craters, however, indicating it is young, geologically speaking. Any craters which did form, like elsewhere on Pluto, were erased by the flowing ice.

With active glaciers and flowing ice, as well as possible cryovolcanoes (ice volcanoes), Pluto is a more dynamic body than many scientists had expected. Somehow this small icy world at the fringes of the Solar System has retained enough heat inside to allow it to still geologically alive. The same is true for its largest moon Charon, which also has tall mountains, canyons, “sunken” hills inside large pits and an odd reddish-colored north polar cap. It is even theorized that Charon may have a subsurface ocean of liquid water, similar to moons like Europa and Enceladus.

“It’s hard to imagine how rapidly our view of Pluto and its moons are evolving as new data stream in each week. As the discoveries pour in from those data, Pluto is becoming a star of the Solar System,” said Stern. “Moreover, I’d wager that for most planetary scientists, any one or two of our latest major findings on one world would be considered astounding. To have them all is simply incredible.”

As also noted in a recent paper:

“The New Horizons encounter revealed that Pluto displays a surprisingly wide variety of geological landforms, including those resulting from glaciological and surface-atmosphere interactions as well as impact, tectonic, possible cryovolcanic, and mass-wasting processes. This suggests that other small planets of the Kuiper Belt, such as Eris, Makemake, and Haumea, could express similarly complex histories that rival those of terrestrial planets. Pluto’s diverse surface geology and long-term activity also raise fundamental questions about how it has remained active many billions of years after its formation.”

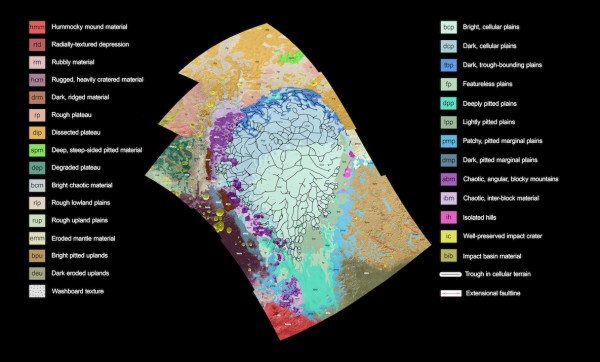

There is also now a new geological map of Pluto, showing Sputnik Planum and surrounding terrain, covering 1,290 miles (2,070 kilometers) from top to bottom. All of the terrain has been imaged at a resolution of approximately 1,050 feet (320 meters) per pixel or better. The possible cryovolcano Wright Mons is the red area in the bottom corner of the map. The map also show the cellular and pitted icy plains, blocky mountains, icebergs, and rugged highlands. The detailed map, depicting such a wide variety of features, is a good example of just how geologically diverse Pluto is, much more so than used to be thought possible. Despite being so small and far from the Sun, Pluto is an active world.

Since it is now known that Pluto is just one of many smaller rocky worlds in the Kuiper Belt, the question now is how many of them are also active? Are they similar to Pluto or is Pluto just an oddball? New Horizons is currently on course for its next encounter, with a smaller Kuiper Belt Object called 2014 MU69, on Jan. 1, 2019. Given what has already been seen at Pluto, it will be interesting to get a close view of this little worldlet next.

“Although this flyby probably won’t be as dramatic as the exploration of Pluto we just completed,” according to Stern, “it will be a record-setter for the most distant exploration of an object ever made.”

The New Horizons mission will also be commemorated this year by the United States Postal Service (USPS) releases two new Pluto stamps later this year, the first ones since 1991. The stamps will be dedicated between May 28 and June 4 at the World Stamp Show, N.Y.C., 2016 at the Jacob Javitz Center—a most well-deserved honor.

As Stern noted: “I’m excited. The New Horizons project is proud to have such an important honor from the US Postal Service. Since the early 1990s the old, ‘Pluto Not Explored’ USPS stamp served as a rallying cry for many who wanted to mount this historic mission of space exploration. Now that NASA’s New Horizons project has accomplished that goal, it’s a wonderful feeling to see this new stamp join the stamps for the first exploration of each of the other planets at USPS.”

New Horizons may be long past Pluto now, but the data is still being sent back to Earth and will be until about October this year. Although the mission was only a flyby, the amount of data obtained is enormous and will keep scientists busy for decades to come.

Follow our New Horizons mission page for regular updates.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

.

Missions » New Horizons »

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:New Horizons Finds Evidence for Frozen Ocean Inside Pluto’s Moon Charon « AmericaSpace