More than a half-century ago, today, one of the hairiest and closest brushes with disaster occurred only moments after the liftoff of America’s second manned lunar landing mission. Apollo 12 Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Dick Gordon and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Al Bean were tasked with executing a pinpoint landing on the Moon’s Oceanus Procellarum (the “Ocean of Storms”), performing two sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) on the surface and supporting a wide range of lunar science investigations. Conrad, Gordon and Bean would become the first Apollo crew to make up their first words on the Moon, the first to use pictures of Playboy girls to guide them to their allotted tasks and the first to float from spacecraft to spacecraft in their birthday suits.

And they would become the only Apollo crew to be struck by lightning.

Their friendship and camaraderie long preceded their selection into NASA’s astronaut corps. Conrad and Gordon had been shipmates in the U.S. Navy, whilst Bean was one of Conrad’s students at test pilot school. Conrad and Gordon flew together aboard Gemini and were teamed again for Apollo 12, alongside fellow astronaut Clifton “C.C.” Williams.

However, Williams’ tragic death in late 1967 prompted Conrad to ask for Bean to replace him. As a crew, the three friends did everything together, even acquiring three gold Corvettes—their licence plates identifying their respective roles on the mission: CDR, CMP, LMP—from contacts at General Motors. Conrad even tried to smuggle a giant baseball cap into his personal belongings; an unsuccessful ruse which might have seen him bounce in front of the television camera on the Moon, wearing it over his helmet. It would give Earthbound audiences a chuckle, he hoped.

But for a twist of fate, Conrad might well have become the first man to walk on the Moon, had Apollo 11 failed. In a conversation with the fiery Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci in the summer of 1969, he became infuriated by her insistence that Neil Armstrong’s famous words had been put into his mouth by NASA brass.

No amount of persuasion would change her mind, so Conrad bet her $500 that he would make up his own words when he set foot on the Moon. And on 19 November 1969, as he stepped off the footpad of the Lunar Module (LM) Intrepid and onto the dusty surface of the Ocean of Storms, the smallest member of NASA’s astronaut corps was true to his word. “That may have been a small one for Neil,” he wisecracked, “but it’s a long one for me!”

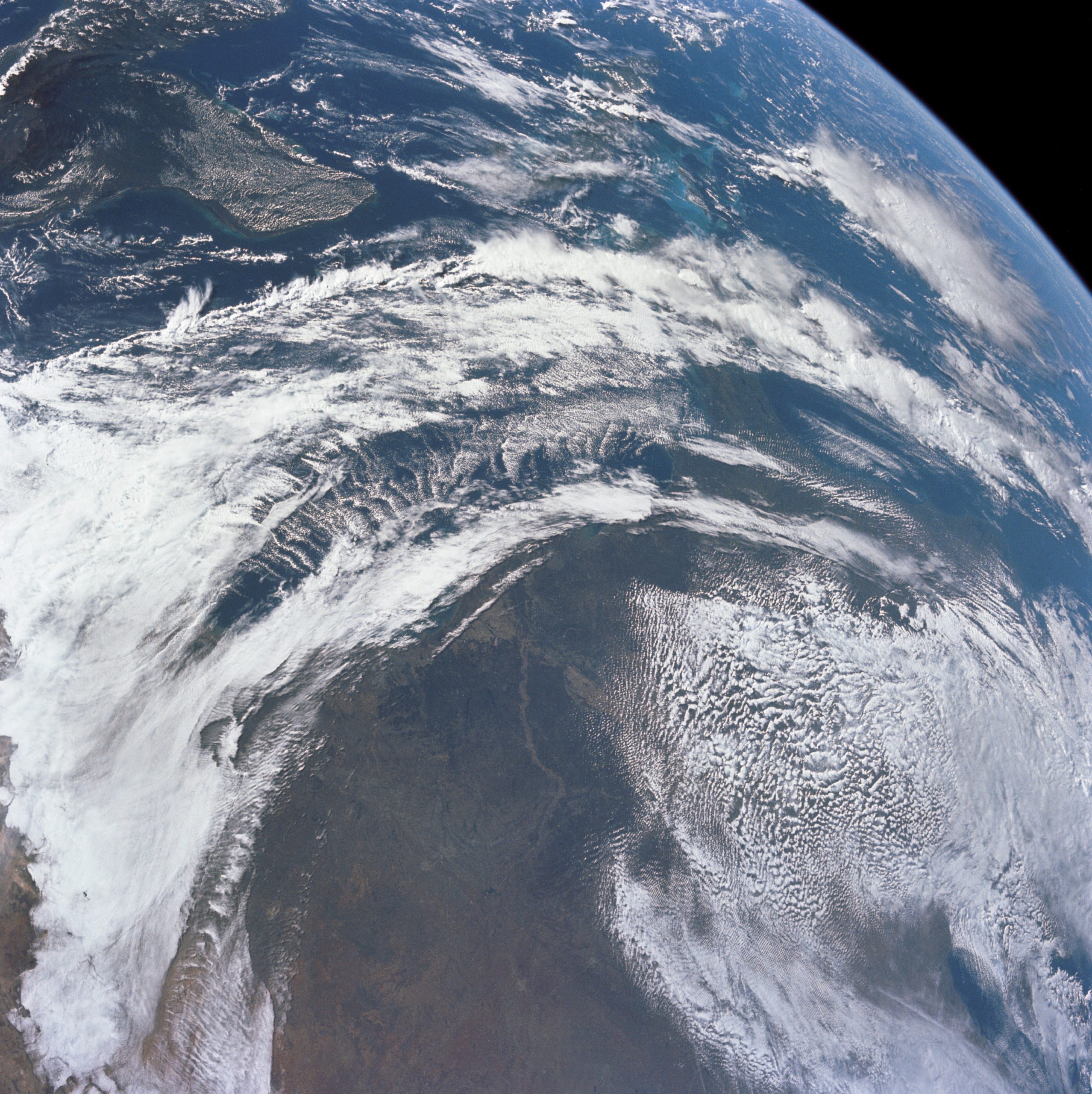

However, getting to the Moon proved problematic right from the start. Whilst Apollo 11 landed 4 miles downrange of its targeted spot in the Sea of Tranquility, Apollo 12’s scope was expanded to achieve a precise touchdown, within walking distance of NASA’s Surveyor 3 probe, which had alighted within a “nest” of craters on the Ocean of Storms in April 1967.

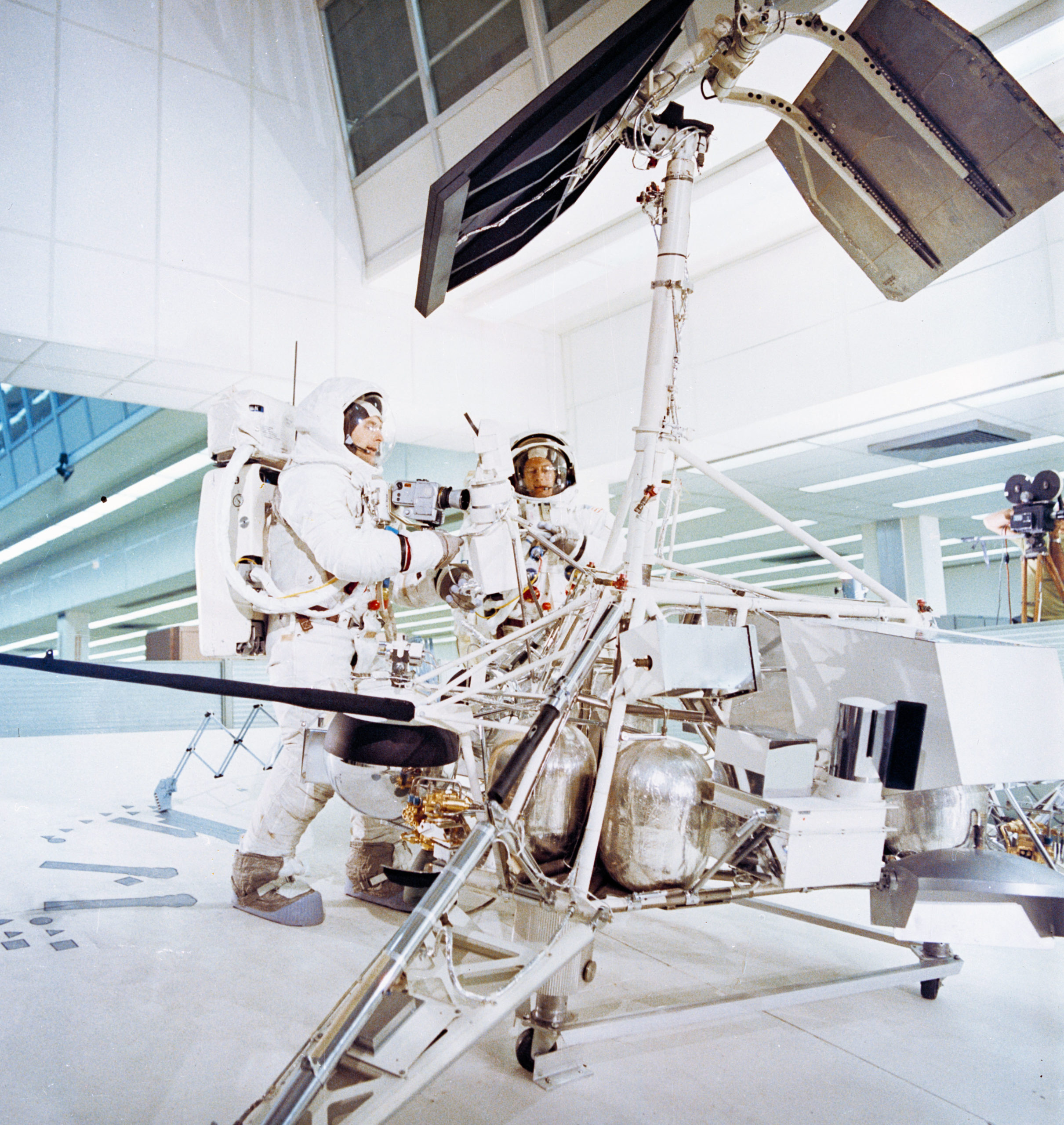

And whereas Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made a single Moonwalk, lasting barely 2.5 hours, Conrad and Bean would leave Intrepid on two occasions, totaling almost eight hours on the surface. The astronauts would visit Surveyor 3, pluck off a couple of its instruments to return to Earth and set up a monitoring station known as the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP).

The naval backgrounds of Conrad, Gordon and Bean led them to designate their LM “Intrepid” and their Command and Service Module (CSM) “Yankee Clipper”, choosing the names from dozens of suggestions posed by workers at North American and Grumman, who built the two spacecraft. Unfortunately, the Apollo 12 backup crew—Commander Dave Scott, LMP Jim Irwin and CMP Al Worden—happened to be an all-Air Force squad and this led to some significant “ribbing” later in the mission.

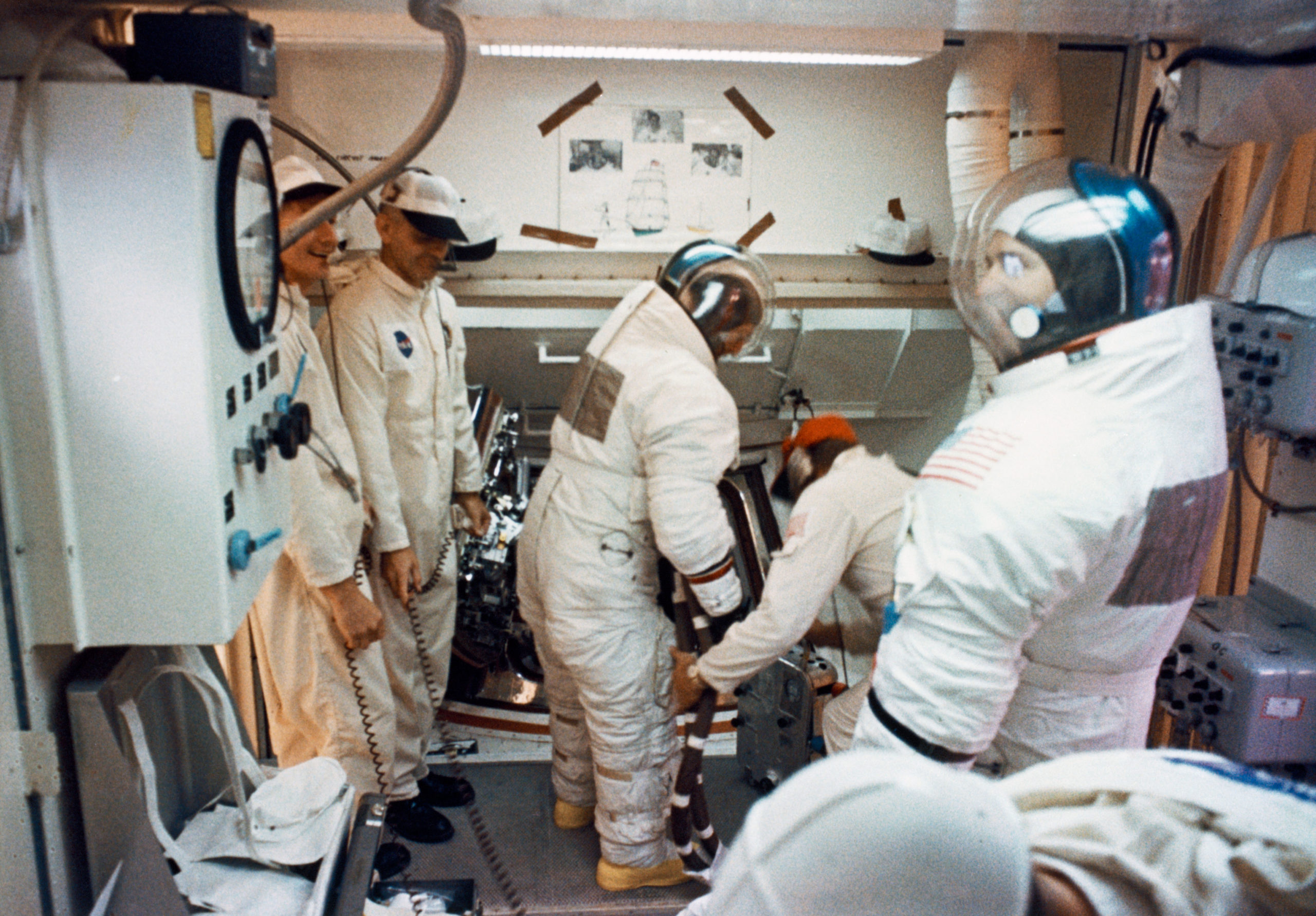

Early on 14 November 1969, Conrad, Gordon and Bean left their crew quarters at Cape Kennedy to cold, grey and drizzly conditions, with rain showers 80 miles (130 km) to the north and a thick layer of overcast cloud at 10,000 feet (3,000 meters).

It seemed probable that Apollo 12 would not launch that day. But the crew boarded Yankee Clipper and lay in their couches as storm clouds rolled overhead, the skies periodically brightening, then darkening. At length, Launch Director Walter Kapryan gave a definitive “Go for Launch” and Conrad responded that the Navy was always willing to support NASA’s all-weather testing. It was a cocky statement that he would live to regret.

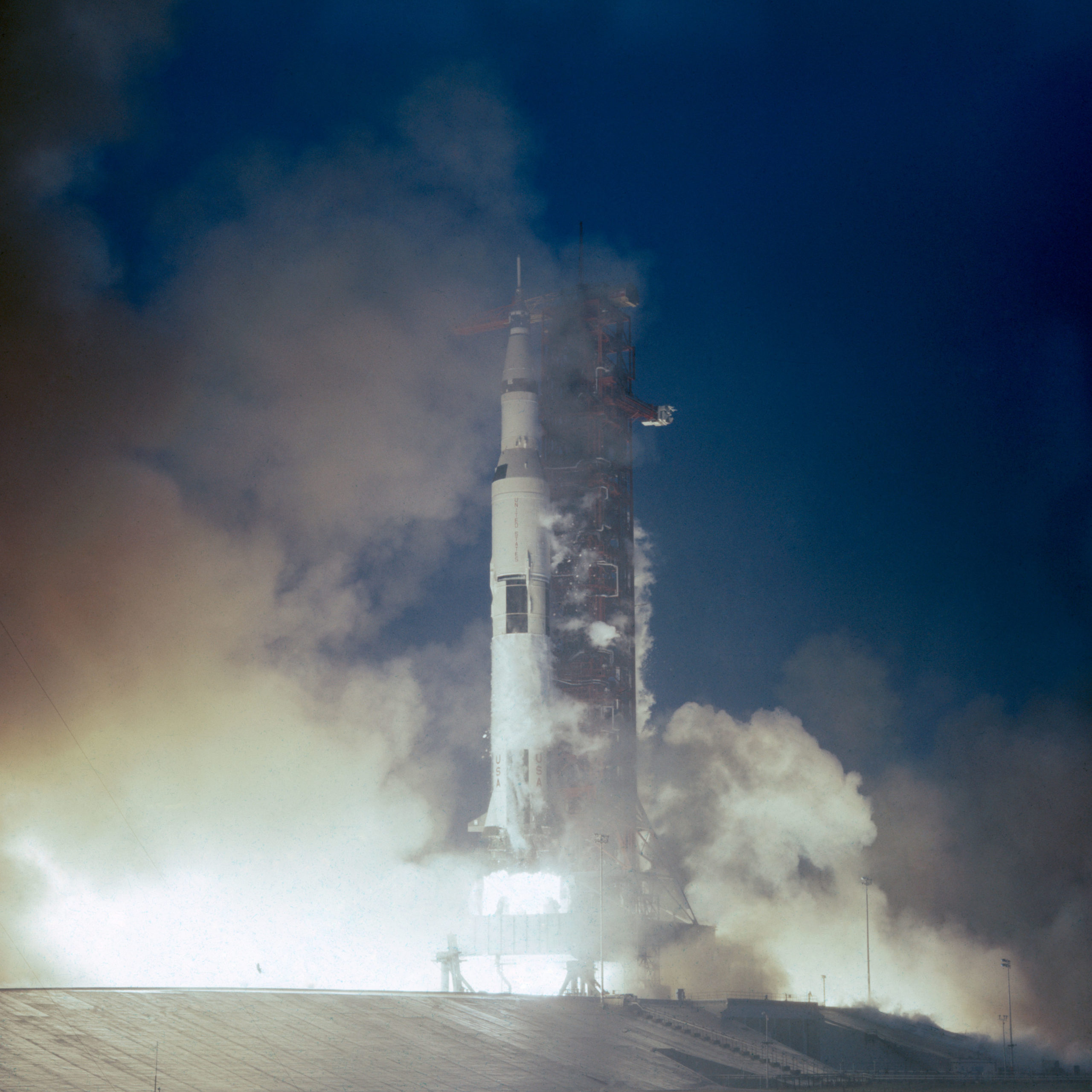

At 11:22 a.m. EST, the Saturn V rocket roared aloft from Cape Kennedy’s Pad 39A, watched by more than 3,000 invited guests, including President Richard Nixon. “It’s slow; very slow,” remembered Gordon in a NASA oral history. “It shakes, rattles and rolls, is actually what it does. It makes a lot of noise and it’s been described as a freight train going straight up. And I guess that’s as apt a description as you can give.”

Quickly, the rocket disappeared into the murky cloud. Then something went badly wrong. For the astronauts, a bright flash, a roar of static, the wailing master alarm and a caution-and-warning panel lit up like a Christmas tree gave them a shock; even their worst simulation had never shown up so many simultaneous failures.

“I got three fuel cell lights, an AC bus light, a fuel cell disconnect, AC bus overload 1 and 2, Main Bus A and B out,” Conrad urgently radioed.

“We never anticipated anything like it,” Gordon recalled years later. “It was not part of the training syllabus! Simulations didn’t even come close to it.” All three fuel cells had gone down, the AC power buses were gone and Yankee Clipper’s gyroscopic platform drifted. “Okay, we just lost the platform, gang,” Conrad calmly radioed to Mission Control. “I don’t know what happened here. We had everything in the world drop out.”

What had happened was that the 36-story Saturn V—the largest and most powerful rocket ever brought to active operational status—had been struck by lightning. The first strike was clearly visible from the ground, hitting the great rocket at 36.5 seconds into the flight and traveling down its long exhaust plume, all the way back down to the pad.

At 1.2 miles (1.9 km) in length, Apollo 12 had unwillingly become the world’s longest lightning rod. Yankee Clipper’s systems shut themselves down in response to the massive electrical surge, but the worst was not over. In a view recorded by long-distance cameras at the launch pad, another strike at 52 seconds knocked out its gyroscopes.

With the spacecraft running on backup batteries, Conrad’s decision was to pull the abort handle and waste several hundred million dollars’-worth of Moonship or wind up in low-Earth orbit with an electrically-dead spacecraft. He chose to hold out as long as possible and, fortunately, the Saturn V’s guidance system was unaffected and delivered them smoothly into orbit. But Flight Director Gerry Griffin was convinced he would have to order an abort. Before he did so, he checked in with the Electrical, Environmental and Communications Officer (EECOM) John Aaron for a recommendation.

And Aaron had seen this problem on a previous simulation. “Flight, try SCE to Aux,” he told Griffin, instructing the crew to move a switch for the Signal Conditioning Equipment to its Auxiliary position. Bean promptly complied and the data returned to Mission Control’s screens. SCE converted raw instrumentation signals into usable computer data and Aaron had effectively saved the second manned landing mission to the Moon.

There was much guts-and-glory in Mission Control that day, none more so than Griffin himself, who made the decision to press on. “It was a decision that only Flight could make,” recalled veteran flight director Chris Kraft. “Gerry made it…one of the gutsiest decisions in all of Apollo and I was proud of it.”

But for Gordon there was another important lesson to be learned from Apollo 12. Years later, NASA interviewer Catherine Harwood asked him if any changes to equipment or procedures were implemented after the lightning strike.

“Yeah,” quipped Gordon. “Don’t be stupid enough to launch in a thunderstorm!”

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » Apollo »

One wonders why NASA decided to launch under such conditions.