Only four years before the first woman and the next man are due to set foot on the surface of the Moon, AmericaSpace and the world mourn tonight, following the passing of Apollo 15 Command Module Pilot (CMP) Al Worden at the age of 88. Worden’s 12-day voyage with crewmates Dave Scott and Jim Irwin in July and August 1971 saw him perform a comprehensive survey of the Moon with a powerful battery of scientific instrumentation, as well as the first-ever “deep-space” Extravehicular Activity (EVA), more than 180,000 miles (300,000 km) from Earth. Worden’s passing brings to just 11 the number of surviving Apollo astronauts who voyaged to our nearest celestial neighbor, all those years ago.

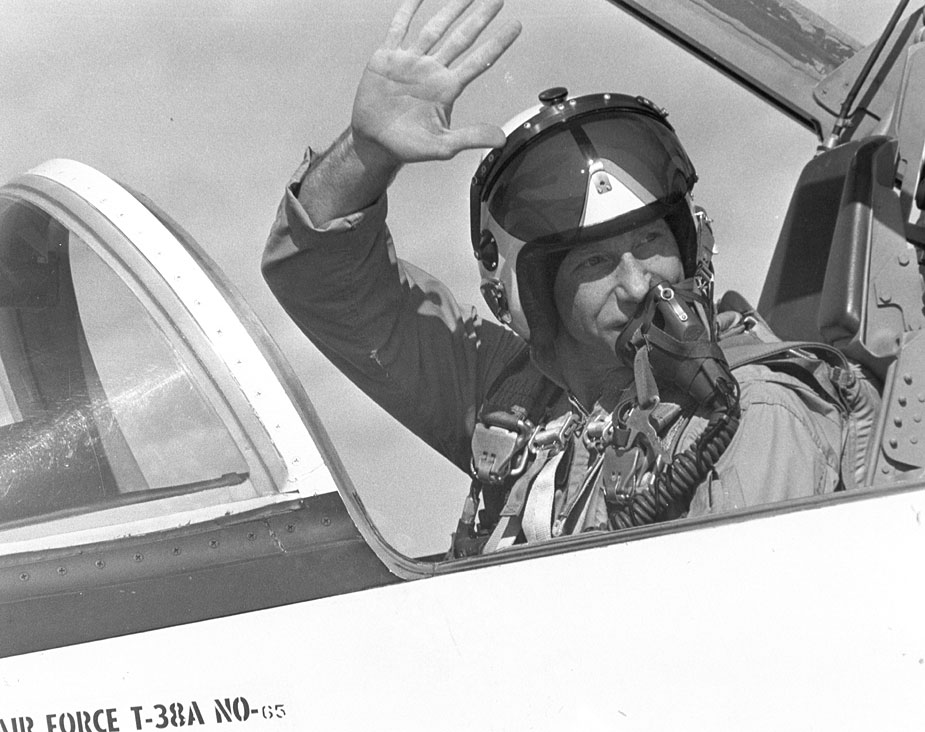

Alfred Merrill Worden was born in Jackson, Mich., on 7 February 1932, the progeny of a farming family. “Aviation was not really something that was foremost in my mind,” he told the NASA oral historian, years later. “From the age of 12 on, I basically ran the farm, did all the fieldwork, milked the cows; did all that until I left for college.” He attended the Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., earning a degree in military science in 1955. Worden hoped to become an army leader, but eventually gravitated to the Air Force, believing the options for promotion were more favorable. He underwent initial flight instruction at Moore and Laredo Air Force Bases in Texas, before transitioning to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida to join an all-weather interceptor squadron.

A master’s degree followed in astronautical, aeronautical and instrumentation engineering from the University of Michigan in 1963, after which Worden was selected for test pilot school. In 1965, the year before he was picked by NASA as an astronaut candidate, he graduated from both the Aerospace Research Pilots School (ARPS) at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., and the Empire Test Pilot School in the UK as part of an exchange program with Britain’s Royal Air Force. By mid-decade, his options were two-pronged: either apply for the Air Force’s (ultimately ill-fated) Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program or tender an application to NASA. Selected in April 1966, his technical duties were focused acutely on the Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) systems and in March 1969 he was appointed Command Module Pilot (CMP) on the backup crew for Apollo 12, which flew in November of that same year.

Following a three-flight rotation pattern, it came as little surprise in March 1970 when the Apollo 12 backup crew was assigned as prime crew for Apollo 15, then scheduled to launch in spring 1971. Worden as CMP would be joined by fellow “rookie” Jim Irwin as Lunar Module Pilot (LMP), together with veteran Commander Dave Scott; the only all-Air Force crew to voyage to the Moon.

Original plans for Apollo 15 called for a “H-series” mission, with no more than 33 hours on the lunar surface and a pair of Extravehicular Activities (EVAs) lasting around 4.5 hours apiece. However, following the traumatic voyage of Apollo 13 in April 1970 and diminishing NASA budgets in the face of civil unrest at home and an increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam, decisions were made to cancel the final two Apollo missions. In order to maximize what was left of the program, Apollo 15 was changed to become the first of the “J-series” of missions, with three EVAs, around 67 hours on the Moon and the use of the battery-powered Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV). Additionally, the CSM would be equipped with a complex Scientific Instrument Bay (SIMbay) of experiments which required Worden to work alone for three days in lunar orbit on a comprehensive series of observations and measurements of our closest celestial neighbor.

“Our purpose,” Worden told the NASA oral historian, “changed from getting there and getting back to going out there and collecting all this science. There was an end game here; there was an end purpose to going. It wasn’t just to go and come back. It was to go out there and really do something scientific that was worthwhile.” Dave Scott was glowing in his praise of Worden, noting that the CMP would be performing all of the duties normally demanded of a three-man Apollo crew during his time alone in lunar orbit, including maneuvers and science and would operate instrumentation that would map around a quarter of the Moon’s surface.

Launched atop the powerful Saturn V booster on 26 July 1971, an experience that Worden described as “a smooth, slow rise from the launch pad in an eerie kind of silence” in his memoir Falling to Earth, Apollo 15 reached lunar orbit four days later. And as Scott and Irwin descended to the Moon’s Hadley-Apennine region to explore the lunar mountains for the first time in history, Worden circled the strange gray world with his own fully-fitted scientific laboratory. “Changes in color and shading fascinated me as I circled the Moon,” he wrote. “Looking toward the Sun, the lunar surface appeared light brown. Away from the Sun, it looked gray.” For three days, he focused his instruments and his eyes on this intractable dead land. During quiet spells, he would play music cassettes and marvel at the spectacle which drifted silently beneath him.

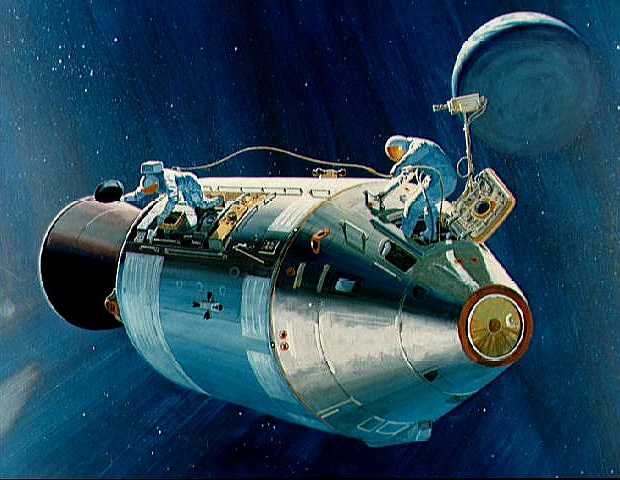

Reunited with Scott and Irwin after their exploration of the surface, Apollo 15 headed for home and Worden had the unique opportunity to perform the first “deep-space” EVA, more than 180,000 miles (300,000 km) from Earth. In one glance, he could see both the home planet and the Moon through his visor faceplate. And for 39 minutes, Worden tumbled in the most unimaginable void, retrieving film canisters from the SIMbay. In Falling to Earth, he compared the blackness to “a fleeting sense of being deep under the ocean”, but Worden’s experience was of a darkness far darker than any ocean. “The blackness defied understanding,” he wrote, “because it stretched away from me for billions of miles.”

On 7 August 1971, Apollo 15 returned safely to Earth, albeit harsher than normal thanks to a failure of one of the command module’s parachutes. An ugly scandal involving first-day postal covers carried to the Moon entered the public domain in 1972 and cost Scott, Worden and Irwin their seats on the backup crew of Apollo 17. None of them ever flew again. It was an intense pity, for Apollo 15 had proven to be one of the most brilliant missions ever undertaken in the annals of space science. With Worden’s passing at age 88, only 11 men now remain alive from the 24 who voyaged to the Moon and back a half-century ago. And of that number, it is a saddening indictment of our failure to return sooner that only four living souls, Buzz Aldrin, Dave Scott, Charlie Duke and Jack Schmitt, can now claim to have actually set foot on its dusty surface. It can only be hoped that in the coming years the next generation of lunar explorers will follow in their footsteps.

.

.

Follow AmericaSpace on Facebook or Twitter!

.

.

Missions » Apollo »

A true American hero. Please read his excellent book, “Falling to Earth.” I seem to recall that there were no photographs taken of his spacewalk with the Moon as a backdrop. R.I.P., Al. You made us proud.

to bad most americans will not know a true hero go into the unknown not knowing if they will return but hopiful to do so poeple today have it too easy back then these guys worked and worked hard and long to acheive those lofty american goals so so long for now and thanks for what you gave us all